The Echo Effect - Our methodology: films

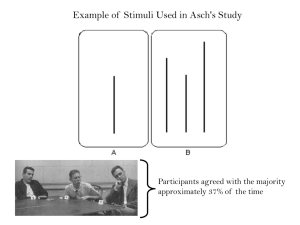

advertisement

1 The Echo Effect: The Power of Verbal Mimicry to Influence Pro-Social Behavior Wojciech Kulesza1, Dariusz Dolinski2, Robert Majewski2 Avia Huisman3, 2 THE ECHO EFFECT Abstract Research on the chameleon effect has demonstrated that social benefits such as liking, safety, rapport, affiliation, and cohesion can be evoked through nonverbal imitation (e.g., body language and mannerisms). Herein we introduce the echo effect, a less researched phenomenon of verbal mimicry, in a real-world setting. Study participants, three-hundred and thirty currency exchange office customers, were assigned into one of three experimental and two control conditions. Careful attention to research design produced results that address issues raised in the mimicry literature, and more clearly define the boundaries of verbal mimicry. The results demonstrate that: while repetition of words is important in increasing an individual’s tendency to perform prosocial behaviors, the order in which they are repeated back is not; verbal mimicry is more powerful mechanism than dialogue; and, for non-mimicry control conditions, no response produces the same result as a brief response. Key words: communication accommodation theory, contact, conversational analysis, emotions, intonation, research method, silencing, speech rate 1 University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Warsaw Faculty; Florida Atlantic University 2 University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Wroclaw Faculty 3 College of Science, Marshall University Corresponding author: Wojciech Kulesza. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Wojciech Kulesza, University of Social Sciences and Humanities , Chodakowska 19/31, 03-815 Warsaw, Poland. Email: wkulesza@swps.edu.pl THE ECHO EFFECT 3 The Echo Effect: The Power of Verbal Mimicry to Influence Prosocial Behavior O, si tacuisses! (Boëthius) Psychological research demonstrates that the way people behave and experience their social world depends upon the stimuli found in the environments they inhabit and situations they navigate through. Research has shown, for instance, that when people move in synchrony with others it results in a feeling of group cohesion, and social connectedness, which in turn leads to creating prosocial tendencies that make them more willing to cooperate within groups (Macrae, Duffy, Miles, & Lawrence, 2008; Wiltermuth & Heath, 2009). Prosocial behaviors are also investigated in the field of social psychology, with many researchers looking into questions related to mimicry and the phenomenon of the chameleon effect (e.g., Müller, Maaskant, van Baaren, & Dijksterhuis, 2012). The chameleon effect is a specific form of synchrony that takes place among dyads rather than within and between groups (for the review see: Chartrand & Lakin, 2013). Nonverbal Mimicry The Chameleon Effect Mimicry is easily observed in human interactions from an early age. For example, imitation between parent and child plays an important role in learning social skills, language, how to obtain food, to avoid danger, and even how to perform aggressive behaviors (e.g., Fukuyama & Myowa-Yamakoshi, 2013; Xavier, Tilmont, & Bonnot, 2013). Also, imitation between children is crucial for establishing social relations. For example, recently it was shown that mutual mimicry induces prosocial behaviors between 4 year old children (Kirschner & Tomasello, 2010). Taken together, it seems that from the beginning THE ECHO EFFECT 4 humans are expert social chameleons, and this tendency to use mimicry to increase social bonds does not expire throughout the life span. As adults we engage in mimicry to establish, and maintain social relations with others (Chartrand & Bargh, 1999), and when we expect prosocial behaviors from others (van Baaren, Holland, Kawakami, & van Knippenberg, 2004). In the literature, this phenomenon has been termed the chameleon effect. The term chameleon effect was coined by Chartrand and Bargh (1999) to describe the effect mimicry seemed to have on an individual who is mimicking or being mimicked (Stel & Vonk, 2010). Their first experiment began by pairing confederates, who engaged in smiling, foot shaking or face rubbing behaviors, with a naïve participant who thought they were there to be part of a serial photo discussion exercise. The authors found that participants smiled more often when the confederate smiled, that those paired with the confederate who shook their foot, shook their feet more, and those paired with the confederate who rubbed their face, rubbed their faces more when compared with participants in the opposite condition or control condition. This result led them to wonder why participants would mimic in this way—what social or adaptive advantage is gained by engaging in such behavior. Their second experiment was designed to probe these questions further. This time, during the interaction, the confederate either mimicked the participant’s body language (posture, gestures, and mannerisms) in the experimental condition or did not in the control condition. Afterwards, participants were asked to complete an exit questionnaire that included rating how much they liked the confederate and how smoothly THE ECHO EFFECT 5 they felt the interaction went. Results were as predicted. Imitation of body language and mannerisms influenced feelings of rapport and liking. In general, within the mimicry literature much of the research concentrates on its nonverbal aspect. Verbal mimicry, on the other hand, has received less attention. In this article we fill this theoretical and empirical gap by presenting an in-depth study exploring boundaries of verbal mimicry as a mechanism responsible for eliciting prosocial tendencies. Nonverbal Mimicry, Social Relations, and Prosocial Behavior Link This research by Chartrand and Bargh (1999) was the first where nonverbal mimicry was systematically manipulated, and the benefits for the mimicker were described. Subsequent research has further expanded our understanding of the chameleon effect, revealing that feelings of safety (Dijksterhuis, Aarts, Bargh, & van Knippenberg, 2000), rapport / affiliation (Lakin & Chartrand, 2003), and trust (Maddux, Mullen, & Galinsky, 2008) can also be generated through nonverbal mimicry. As a consequence the chameleon effect began to be perceived as a foundation of social relations: a “social glue” (Lakin, Jefferis, Cheng, & Chartrand, 2003). From the perspective of the present study, there are, however, two especially important papers describing other aspects of “social glue”. One shows a new link between nonverbal mimicry and prosocial tendencies. The second explores the less researched verbal aspect of the chameleon effect. As these articles are the launching pad for the present study, they are described in detail below and placed within the broader context of the mimicry literature. First, we will discuss groundbreaking research by van Baaren et al. (2004). Their study was the first to show that mimicry, used strategically, might be a powerful tool of THE ECHO EFFECT 6 eliciting prosocial behaviors. The authors demonstrated that a confederate who mimicked the posture (position of arm, legs, etc...) of participants elicited the willingness of participants to help the confederate pick up pens she “accidentally” dropped on the floor and to donate significantly more money to charity (a Dutch foundation), than in the instances where they did not mimic the participants. Interestingly, in another study (Stel, van Baaren, & Vonk, 2008) tables were turned. Now it was a participant who mimicked (or not) the person who was representing the charity organization, and talking about the necessity of helping animals. As a result, participants donated significantly more money (1.06 Euro), when they were asked to mimic, than in the non-mimicry condition (0.30 Euro). Verbal Mimicry Mimicry is also influential, providing adaptive (e.g., learning: Guerrero & Commander, 2013) and social advantage, when in its verbal form (spoken: Goode & Robinson, 2013, and written: Ireland & Pennebaker, 2010). For example a study by Simner (1971) has shown, that newborns will mimic the vocal expressions (crying - as a proxy for vocal communication) of one another (e.g., cry less when exposed to silence), and will not mimic, synthetic newborn crying of the same intensity (Sagi & Hoffman, 1976). As in Chartrand and Bargh (1999) two questions arise: (1) how exactly this verbal process takes place, and (2) what social advantages are gained by engaging in such imitative behavior. While answering these questions, let us begin with an overview of two crucial theories in the field of linguistic accommodation that explore the motivation for verbal imitation. One theory, the interactive alignment model, describes imitative behavior as automatic and uncontrolled (Goldinger, 1998; Pickering & Garrod, 2004). According to this THE ECHO EFFECT 7 theoretical concept, every level of linguistic representation (i.e., the situation model, semantics, syntax, lexicon, phonology, and phonetics) is connected within an individual’s mind. Moreover, each level of representation between the listener and the speaker is again interconnected. An automatic and unconscious process that percolates through the levels of representations of interaction partners serving to align their speech. The use of a particular linguistic representation by a speaker leads, in turn, to the activation of the same representation in the listener. There is, however, one caveat to this line of reasoning. As noted by Prinz (1990) while describing syntactic persistence: “the ability to produce language is of no use when there is no one to listen, and the ability to understand language is of no use when there is no one to produce it” (pp. 177). One might say, then, that it seems when conceptualizing verbal imitation we are still missing an end goal or clearly definable reason for such unconscous verbal behaviors. Such may be found in a review by Garrod and Pickering (2009), where it was shown, that verbal imitation leads to emulation of interlocutors’ expected behavior. In addition, a more concrete answer to that caveat may be easily found in another fundamental theoretical construct. Here we refer to the communication accommodation theory (Giles, 1973), where it was shown, that imitation not only activates the same representations between two parties of an interaction, but serves an important social function. According to this theory, the speaker modulates social distance by converging or diverging speech patterns of speakers (Shepard, Giles, & Le Poire, 2001). Language is, therefore, a tool used by speakers to achieve the desired social distance between themselves and others. To achieve it communicators may adopt any one of four strategies in speech: THE ECHO EFFECT 8 convergence, divergence, maintenance, and complementarity. Convergence, which is of particular interest here due to similarities with the verbal aspect of the mimicry phenomenon, arises when speakers alter their linguistic patterns to adopt styles more like that of their interaction partners (see also: Mantell & Pfordresher, 2013). For example, in Giles (Giles, Taylor, & Bourhis, 1973), French and English Canadian bilinguals attempted to speak French to English-dominant listeners. By accommodating to the linguistic needs of English listeners, bilingual speakers were evaluated more favorably. Moreover, it has been shown that the English listeners reciprocated the perceived favor by speaking French in a subsequent task. Thus, the verbal mimicker, just like the behavioral mimicker, socially benefited from mimicry by establishing “social glue” with the mimicked party of the interaction. Stemming from the findings of Giles et al. (1973) we may assume that the impact of linguistic courtesy on behavior is easily attributable to socio-cultural factors, while the pattern of phenomena resulting from mimicry is thought to be innate. During a conversation with a person whose first language is one you know how to speak, changing to their language to facilitate communication is a conscious choice. In contrast, during that same conversation verbal and nonverbal mimicry may be present, but the interlocutors will not be conscious of its presence, or influence. Importantly, however, for those who are aware of the power of verbal mimicry, it may be used consciously and strategically (as in van Baaren et al., 2004) to provide a variety of benefits for the mimicker. Illustration of this notion is found in Swaab, Maddux, and Sinaceur (2011) where the link between verbal mimicry, negotiations, and mutual benefits for the mimickee and the mimicker were investigated. The THE ECHO EFFECT 9 first experiment demonstrated that negotiators, who via an on-line chat program, mimicked their counterpart’s language and verbal expressions (such as specific words, grammar, jargon, metaphors, or abbreviations) at the beginning of a negotiation game, ended the game with a higher income than those who mimicked at the end of the game or did not mimic at all. In the second experiment analysis revealed that early mimickers elicited more trust. Another example in which verbal mimicry was used consciously and strategically to influence the mimickee’s opinion can be found in Tanner, Ferraro, Chartrand, Bettman, and van Baaren (2008). Here the authors conducted a series of experments pairing mimicry with a product marketing secnariro. During the second experiment, when the participants arrived they were informed that they would be participating-with an interviewer-in marketing research for a new prototypical sport drink called Vigor, which was approaching market launch. While conducting the marketing research the interviewer (in fact a confederate) mirrored the gestures of the participant, and imitated the participant’s comments, as if to verify what they said. For example, if a participant said that, “I tend to drink Coke and Sprite mostly,” then the confederate would conclude, “So you drink Coke and Sprite mostly”. Importantly, in the control condition the interviewer spoke a sentence in an equal length to participants’ statement, but none of the words were mimicked (so the reply would be: “Ok, I got your views on that one”). The results provided evidence that participants who were nonverbally and verbally imitated by the confederate provided significantly higher ratings of Vigor (or snacks - in the third experiment) than those who were not mimicked. Verbal Mimicry Research in the Real-world THE ECHO EFFECT 10 Now let’s turn our attention to van Baaren (van Baaren, Holland, Steenaert, & van Knippenberg, 2003), the second groundbreaking experiment mentioned earlier as inspiration for the current research, and several follow up studies stemming from their work. This study was conducted in a naturalistic setting (restaurant) where a trained waitress interacted with naïve diners to see if there was a difference in tip percentages between tables where she either did, or did not, verbally repeat orders back to customers. In the first experiment the waitress either repeated everything the customers said to her, or, in the control condition, she responded with brief statements like, “okay!” or “coming up!” The results (on the level of trend) revealed an increased tip average for customers who were mimicked (2.97 Dutch guilders (NLG) vs. 1.76 NLG). One of the caveats of that study was that in the non-mimicry condition the waitress might be perceived as inattentive, hence decreased tips would not be a result of non-mimicry. Therefore, in the second experiment the naïve waitress made it clear that she understood the order by writing it down so presumably clients knew it was understood, and a baseline was established by calculating her general tip average. In this case, the main effect for mimicry was highly significant (2.73 NLG vs. 1.36 NLG), but the difference between the baseline condition and the mimicry condition was only marginally significant. Another study providing evidence for the power of verbal mimicry was carried out in a real-world retail setting by Jacob, Guéguen, Martin, and Boulbry (2011). In this case, sales clerks in a large store specializing in the sale of household appliances either engaged in verbal and nonverbal mimicry of customers who approached them for advice or did not. For instance, if a customer said, “Excuse me, could you please give me some advice about an THE ECHO EFFECT 11 MP3 player?” in the mimicking condition, the salesperson would say, “Advice about an MP3 player? Yes, of course.” Similarly to van Baaren et al. (2003, but differently to Tanner et al. 2008), in the non-mimicking condition, the salesperson would only say, “Yes, of course.” In this experiment, and two that followed, it was found that imitation was associated with higher sales percentages and greater compliance with the seller’s suggestion. An exit interview revealed also that mimicry led to a more positive evaluation of the mimicker and the store where they were employed. Finally, in a recent study by Guéguen (2009) conducted during speed-dating parties in the local pubs, a female confederate was asked to mimic some of an opposite-sex participant’s verbal expressions (i.e., “It’s great,” “It’s fun,” or when the participant asked: “You really do this?” she replied: “Yes, I really do this”), together with his gestures. In the non-mimicry condition, the confederate was instructed to not mimic the verbal expressions (remain silent what makes this condition incomparable in the light of aforementioned studies) of the men. Analysis revealed that participants liked the interaction with the verbally mimicking confederate, and evaluated her sexual attractiveness more highly than in the non-mimicry condition. Weaknesses and Limitations in the Verbal Mimicry Literature Although the studies described above concerning the role verbal mimicry play in interpersonal relations seem to be definitive, several concerns need to be addressed. Primary among these is the fact that to-date it is still not clear exactly what verbal mimicry is and is not. It is not known, for example, if it is necessary to repeat an interlocutors words in the same order they were said (as in all the aforementioned experiments), or if they can be THE ECHO EFFECT 12 presented in a different, but still logical, order (not evaluated as a condition in the aforementioned experiments). Similarly, it is not clear whether the paraphrasing of an interlocutors statement is still mimicry or if it is not (Guéguen, 2009) attempted to shed light on this issue, however, due to mixing verbal and nonverbal mimicry in the experimental design it remains unclear). So, we can say that the weakness (or at least ambiguity) in the design of experimental studies investigating the role of mimicry in increasing occurrences of prosocial behaviors, lies with the responses in the experimental and control conditions. The brief statements given in the control conditions may have been perceived as inattentiveness by the participants in comparison to longer statements expressed by the confederate (Jacob et al., 2011; van Baaren et al., 2003). Whereas, when fully repeating the order back during the experimental condition, the participants may have perceived the partner as more attentive, thereby boosting their desire to leave a better tip (van Baaren et al., 2003) or to buy a product presented or recommended by him or her (Jacob et al., 2011; Tanner et al., 2008). It is also unclear whether compliance, observed in the aforementioned studies, is the result of mimicry, or, perhaps, mere conversation (as in Guéguen, 2009) was enough to produce such effects? With this last question in mind let us consider the findings of Dolinski, Nawrat, and Rudak (2001). Their social influence research demonstrated that when a request was preceded with casual dialogue between the requester and the respondent, the request was more likely to be fulfilled than under conditions where a request was made following a monologue type interaction. This seems to imply that engaging in a didactic social interaction with a second person may be enough to obtain compliance. THE ECHO EFFECT 13 Turning our attention only to the control condition in each of the real-world studies described above, we find some differences. In some experiments the control condition was repeatedly defined by a brief verbal response (i.e., “OK” or “Coming up” in van Baaren et al., 2003; or “Yes, of course” or “Yes” in Guéguen, 2009; or “Yes, no problem” in Jacob et al., 2011). In other (Tanner et al., 2008), the confederate used words different from the participants’, but, importantly, the length of the response was identical. Finally, in Guéguen’s study (2009) sometimes the confederate did not say anything at all. This again raises the problem of ambiguity. It may, in the case of van Baaren et al. (2003) and Jacobs et al. (2011), be that the brevity of expression in the control conditions could not arouse sympathy in the participants towards interaction partners and thus did not lead participants to altruism, and/or compliance. To avoid such a confound, future experimental design should include, not only a brief verbal response, but also additional conditions—one with a total lack of verbal response (like e.g., Guéguen, 2009-- where in this condition no behavioral reaction was performed), and yet another with a long verbal response that is not a simple repetition of interlocutor’s words (e.g. Tanner et al., 2008). Finally, in van Baaren et al. (2003) groups (ranging in size from approx. 2.35 to 2.19 people depending on the experiment)-not dyads-were mimicked, which makes this study more attached to the synchrony phenomenon, rather than mimicry and the chameleon effect. Second, it is not clear who it is important to be verbally mimicked to elicit generous tipping behavior? 1) The payer’s guests’; 2) the payer’s behavior; or 3) both? Research Goals and Design THE ECHO EFFECT 14 The aim of our study is twofold. First, to more clearly delineate the boundaries around, and more precisely define, verbal mimicry. Second, to address a theoretical and empirical gap of verbal mimicry: the link between verbal mimicry and prosocial behaviors. Namely, in the first experimental condition participants’ statements were copied by the confederate exactly as stated (i.e., van Baaren et al., 2003; Jacob et al., 2011; Guéguen, 2009; Tanner et al., 2008). During the second experimental condition, the confederate changed the syntax (word order) of the participant’s statement, while keeping the words used the same. In the final experimental condition, the confederate spoke the same amount of words as the participant, but the words they stated were different from the participants’. This last experimental group was designed to consider the findings of Dolinski et al. (2001) through the lens of verbal mimicry. To address control condition ambiguity issues observed in the previously discussed experiments’ control conditions, two controls were included in the current research. The first was comprised of a brief verbal response by the confederate to the participants’ statement (e.g., van Baaren et al., 2003; Jacob et al., 2011). The second was defined by a total lack of verbal response by the confederate to the participants’ statement, making this condition parallel to the control condition of Guéguen (2009). Another issue concerning experimental design worth mentioning is the potential for a gender effect (see: Rind & Bordia, 1995). Based on results from behavioral mimicry research discussed previously, gender does not seem to play a crucial role in the outcome of behavioral mimicry interactions even in experiments concerning the role of facial attractiveness (van Leeuwen, Veling, van Baaren, & Dijksterhuis, 2009). On the other hand, THE ECHO EFFECT 15 however, there is empirical evidence that gender may play some role in more naturalistic settings where mimicry takes place (Guéguen, 2009), and more generally, in compliance research same/other sex gender plays sometimes a crucial role (e.g., Dolinska & Dolinski, 2006). Importantly though, this factor was not taken under the empirical investigation in the field of verbal mimicry (gender data were not recorded by e.g., van Baaren et al., 2003; Swaab et al., 2011). Speaking of theoretical and empirical gaps, in the present study we want to see if verbal mimicry, like nonverbal mimicry, creates prosocial tendencies. A quick review of the literature described above helps to realize that, to-date there are no studies on verbal mimicry where the impact of this mechanism on prosocial behaviors was investigated. In the present study we postulate one hypothesis and three research questions. Our hypothesis focuses on the question of verbal mimicry as a mechanism for eliciting tendencies to engage in prosocial behaviors. We expect, that verbal mimicry (just like its nonverbal form) will result in greater tendencies to engage in helping behaviors, in comparison to non-mimicry conditions. The first research question concerns the basis and nature of verbal mimicry and asks if it is important, while eliciting prosocial behaviors in the participant, to literary repeat hers/his words, or would it be sufficient to repeat these words without holding the exact syntax order? The second question stems from the uncertainty of whether previously reported compliance resulted from verbal mimicry, or simple and casual interaction. In other words, this question touches methodological issues. The last question asks about the role of gender in verbal mimicry. Since, in the present study, only a male confederate THE ECHO EFFECT 16 verbally mimicked participants, we have to limit our research question to the role of the participants’ gender. Namely, does it matter if a female or male participant is verbally imitated by the male experimenter? Experiment Method Three-hundred and thirty customers at a currency exchange office participated in the experiment (165 women and 165 men of Polish origin). Participants were randomly assigned to one of five conditions (three experimental and two control groups) differentiated by the male cashier’s response to participants’ verbal statements. During the first experimental condition the customer’s statement was imitated (Guéguen, 2009; Maddux, et al., 2008; Swaab et al., 2011; Tanner et al., 2008; van Baaren et al., 2003). Word order was held constant, as was the content of the statement (i.e., number of words used). For example, the customer said, “Transaction: exchange of 1,000 US dollars,” and the cashier said, “Transaction: exchange of 1,000 US dollars.” This condition was labeled copy. The second experimental condition changed the word order used by the customer but used the same words. For example, if the customer said, “Transaction: exchange of 1,000 US dollars,” then the cashier might say, “Transaction: 1,000 US dollars exchange.” This condition was labeled paraphrase. In the third experimental condition the cashier only imitated the number of (different) words used by the customer, responding with a (pretested) statement related to the context of a currency exchange office. Thanks to the setting where the experiment took place, and the experience of the cashier (see below), we were able to prepare a set of statements for the confederate to use. The cashier’s competence in counting THE ECHO EFFECT 17 the words, and speaking back with the exact number of words was also pretested. This kept the situation natural and excluded the effect of surprise, and at the same time was similar to a natural dialogue interaction (see Dolinski et al., 2001). One has to say, however, that there was no real dialogue in the strictest sense, because there was no direct semantic relation between statements expressed by the customer and the cashier. However, statements provided by the cashier still fit with the typical script of currency exchange conversation. For example, if the customer said, “Transaction: exchange of 1,000 US dollars,” the cashier might respond, “The currency exchange rate varies lately.” This condition was labeled dialogue. The first control condition replicated procedures from other studies using a brief acknowledging statement in response to the customer’s request (Jacob et al., 2011; van Baaren et al., 2003). For example, the customer would say, “Transaction: exchange of 1,000 US dollars,” and the cashier would reply, “OK” or “Right away!” This condition was labeled control 1. The second control condition was derived from nonverbal mimicry studies where the confederate made no behavioral response (Guéguen, 2009). For example, if the customer said, “Transaction: exchange 1,000 US dollars,” the cashier said nothing and simply carried out the exchange of currency. This condition was labeled control 2. The experiment was conducted at a foreign currency exchange office in Wroclaw, one of the largest cities in Poland. The cashier1, a man in his forties with 17 years of experience working in foreign currency exchange offices, was blind to the hypothesis. He was located behind a bulletproof window. Participants were selected based on specific criteria. First, they had to be alone. This reflected the dyad style of experimentation from nonverbal chameleon effect THE ECHO EFFECT 18 experiments. It also excluded self-presentation behaviors (e.g., donating to charity in the presence of another person so they can demonstrate that they are a good person - Rind & Benjamin, 1994). Participants also had to be exchanging money only into Polish Zloty (PLN), due to the fact, that in the end of the interaction they would be asked to donate the money to the charity (as a proxy for helping tendencies). Otherwise not giving the money would have two possible explanations: due the bad experimental manipulation, or not having money to donate (see also: Stel et al., 2008, where participants were paid for taking part in experiment to ensrue that they hold some money to donate). Finally, participants were all native Poles to ensure a high level of competency in the language.2 Customers at the currency exchange office were randomly assigned to one of the three experimental conditions, or two control conditions. The cashier was highly experienced, but nevertheless also trained by experimenters to ensure that all behaviors, outside of those manipulated in the study, were the same across conditions. This ensured he spoke with the same tempo (Webb, 1969), accent (Giles & Powesland, 1975), pauses (Cappella & Panalp, 1981), and tone of voice (Neumann & Strack, 2000) in every condition. It is worth noting that in each condition the customer could see their request being carried out immediately and correctly; after the money was collected by the cashier, he calculated the currency rate and handed over PLN. In this way we have excluded a challenge not fully managed by van Baaren et al. (2003), where the order was delivered several minutes after verbal mimicry was performed by the waitress, and may have influenced clients behavior or attitude by introducing the potential for their perception of her behavior as inattentiveness. THE ECHO EFFECT 19 The current experiment mitigates against this issue by ensuring the customer was always immediately certain their order had been understood properly. Following the experimental design of van Baaren et al. (2004; for other studies where such dependent measure was introduced see: e.g., Fischer-Lokou, Martin, Guéguen, & Lamy, 2011; Guéguen, Martin, & Meineri, 2011; Müller et al., 2012; Stel et al., 2008), upon concluding the transaction, the cashier addressed the customer suggesting that they donate money to support a disabled student named Mateo who attends high school near the currency exchange office. They were informed that the money would be used by the Sunshine Foundation (an organization that supports disabled people) to purchase a walker for him (the foundation is real and is well known in Poland, so there was no need to return the money, or debrief the participants after the experiment ended). After the experiment concluded in April of 2010, all of the donated funds were immediately wire-transferred to the Sunshine Foundation for the purchase of Mateo’s walker. The experimental design ensured that participants had Polish currency as it had just been given to them. When the interaction ended and the customer left the exchange office, the value of each participant’s donation was recorded, as were the details of the transaction (Euro 56.9%, British Pounds - 16.9%, and US dollars - 16.6% with other currencies making up the remaining 9.6%), and the gender of the participant. Results A preliminary analysis revealed that the dependent variables (frequency of donation and average amount of money donated) were not affected by participants’ gender (χ2 < 1; F < 1). Also, interaction effects of gender and experimental conditions were not statistically THE ECHO EFFECT 20 significant (χ2 < 1; F < 1) and for this reason the gender variable was dropped from further analysis. In the first step of the remaining analyses we compared two of the mimicry conditions: copy and paraphrase. The results revealed no difference in the frequency of donation (84.4% in the copy condition and 91.1% in the paraphrase condition; χ2 = 1.43, n.s.). Also, the average amount of money given was almost identical in the two conditions: M = 3.41, SD = 2.69 in the copy condition and M = 3.00, SD = 2.24 in the paraphrase condition; F < 1, n.s. Comparison between the two control conditions shows statistically significant differences in frequency of donation. In control 1 customers donated money more often (66.7%) than in control 2 (48.5%) - (χ2 = 5.27, p = .022, φ = .20), but there was no significant difference between the two groups in the average amount of money given (M = 1.24, SD = 2.85 vs. M = 0.49, SD = 0.84, F < 1). Due to this pattern of results, the experimental groups of copy and paraphrase were combined for all subsequent analyses, and the control groups (control 1 and control 2) were combined for analysis of the average amount of money donated, but not for analysis of frequencies of donation. The differences between mimicry conditions and control conditions were significant both in frequency of donation (χ2 = 12.34, p < .001, φ = .25 for comparison with control 1 group and χ2 = 36.18, p = .001, φ = .40 for comparison with control 2 group) and in average amount of money donated: F(1,262) = 67.58, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.02. Finally, donations from customers in the mimicry conditions were compared with the dialogue group and the dialogue group was compared with the combined control groups. The results showed no difference in donations during the mimicry conditions (87.9% vs. 21 THE ECHO EFFECT 80.3% - χ2 = 2.02, n.s.), but they gave more money than participants in dialogue condition: F(1,196) = 6.31, p = .013, Cohen’s d = 0.36. In the dialogue condition people donated money more often than in control 2 (χ2 = 14.57, p < .001, φ = .33) but differences between dialogue and control 1 were only marginally significant (χ2 = 14.57, p = .07). In the dialogue condition people gave significantly more money, however: F(1,196) = 11.26, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.47. Table 1 summarizes all the percentages of donations and the average amount of money donated in the five experimental groups. /Insert Table 1 around here/ Discussion First of all, the present results confirm the hypothesis that verbal mimicry is a powerful tool for inducing prosocial tendencies toward mimicker. Specifically, participants in mimicry conditions donated more often and gave more money than participants both in the dialogue condition and in the control conditions. The results presented here are new and unique in the literature of verbal mimicry. To the best of our knowledge, no research has examined prosocial behaviors as a consequence of verbal imitation presented by the confederate. The Echo Effect: Re-defining Verbal Mimicry In addition, our results suggest the definition of verbal mimicry may need to be more precise. To benefit one must copy the words of the person with whom they are conversing, but they do not necessarily have to use them in the same order. The percentage of customers who donated and the average amount of money given did not differ between the copy and paraphrase experimental conditions. On the other hand, the differences between the THE ECHO EFFECT 22 mimicry conditions and the dialogue condition suggests that just simply responding to, or speaking with someone, even when using the same number of words, is not sufficient to elicit prosocial behavior in the same extent. Participants in the dialogue condition were less likely to make a donation, and, when they did, gave significantly less money in comparison with participants in the mimicry conditions. Furthermore, analysis of the control conditions shows that a brief response (as in van Baaren et al., 2003 or in Jacob et al., 2011) results in the same willingness to engage in prosocial activities as no response (as in Guéguen, 2009). Also, across both control conditions, participants donated money for charity less often, and gave less money when they did, than in the dialogue condition (as in Dolinski et al., 2001; Dolinski, Grzyb, Olejnik, Prusakowski, & Urban, 2005). When examined as a group, the results of the experimental conditions reveal that simply imitating the act of speaking (dialogue condition) is not the same as verbal mimicry. Therefore, since the verbal mimicry resembles the natural phenomenon of the echo, and in fact operates in much the same way, herein we propose to coin this special form of mimicry: the echo effect. Contrary to behavioral mimicry, when engaging in verbal mimicry it is only important to mimic specific acts of communication (individual words). Imitating syntax or the act of speaking (dialogue) is not sufficient to elicit prosocial behaviors in the mimickee, making this result new in the literature of mimicry and the sub-field of research into the chameleon effect. Namely, in previous research when nonverbal behaviors were taken under empirical investigation, the conclusion was that every behavioral imitation benefits the mimicker. In the case of present study, we report precise boundaries for mimicry’s THE ECHO EFFECT 23 verbal form. The results also did not show impact of gender on altruism and compliance, which, in light of previous research on the chameleon effect, is not surprising or unique. The Echo Effect, Prosocial Behavior and Social Influence Verbal mimicry, like behavioral mimicry, has downstream consequences for the mimicker. As with the nonverbal aspect of the chameleon effect (e.g., Fischer-Lokou et al., 2011; Guéguen et al., 2011; Müller et al., 2012; Stel et al., 2008; van Baaren et al., 2004), our results demonstrate that the echo effect can lead to mimicked individuals engaging in prosocial behaviors more frequently than those who are not mimicked. Thus, results from the current study lend support to the theory that mimicry facilitates ones willingness to engage in helping behavior irrespective of the nature of the mimicry (nonverbal vs. verbal). The results did not show an impact of gender on altruism which is in line with other studies. Speaking from more general perspective, the expanded experimental and control conditions employed in the current study addressed an important concern raised by van Baaren et al. (2003) “it is not possible to give a definite answer to the question whether mimicry actually increases tips or whether non-mimicry decreases tips” (p. 396). In the present research, comparison between the mimicry conditions and the dialogue group, and comparison between the dialogue condition and the control conditions, show that it is mimicry that increases the tendency to reward the mimicker, rather than non-mimicry decreasing it. Limitations The present study is initial rather than definitive, thus it has some limitations. For example, the confederate was supposed to use exactly the same number of words as the THE ECHO EFFECT 24 customer in the dialogue condition, while at the same time to not repeating or paraphrasing them. Due to the varied statements made by the exchange office customers, it was not possible to repeat one single response each time. As a result, the cashier had to use slightly different statements (selected from the previously prepared and tested list) each time, which we recognize as a limitation. How this may have influenced the experimental results we cannot determine. On the other hand we are mindful of the fact, that one might find exactly the same differences in van Baaren et al. (2003) and Jacob et al., (2011), where the confederate also replied with varying responses in the control condition (e.g., “coming up” or “ok”). Also in Chartrand and Bargh (1999) study, the confederate was instructed to mimic gestures, and body position of the mimickee. Because of live interactions small differences between experimental conditions had to take place. Thus such differences between consequent interactions are inherent, thus impossible to completely rule out. However, this issue has not been raised or tested in the literature previously, future studies should seek to control this factor. A critical reader might notice that in the experimental design we did not employ a "real dialogue" condition. In previous studies on the use of dialogue as a social influence technique (Dolinski, et al 2001, 2005) compliance was elicited by a direct semantic relation between statements expressed by experimenter (requester) and participant. It is clear, that it is not the case in the present study. This was done on purpose. In the present study our goal was to assess the link between verbal mimicry and elicited in this way helping behaviors per se. We did not intend to determine whether verbal mimicry was more efficient social influence technique than dialogue. Of course such a comparison of both techniques would THE ECHO EFFECT 25 be interesting and important from a theoretical and practical point of view, but it was not the goal of present study. Experiments conducted in real-world settings will always face challenges that may not be able to be fully controlled, but that does not mean they should not be conducted (e.g., van Baaren et al., 2003; Jacob et al., 2011). In this case, since the experiment was conducted (due to the many methodological and theoretical reasons listed above) in the natural setting of a currency exchange office, where, as in a bank, strict rules of anonymity and security are necessary. As a result the interactions could not be recorded, making impossible future analysis and coding of the confederate’s statements. Therefore, though we trust the confederate and believe he complied with the experimental guidelines, we could not verify whether the statements by the confederate might have unduly influenced the customer’s willingness to donate money for charity. In future studies, where recording is possible, the interaction between the confederate and the participant should be recorded, and the transcribed conversation should be verified3. Future Directions As mentioned before, the goal of this study was to investigate whether verbal mimicry is an effective technique for eliciting prosocial behaviors, rather than to assess whether mimicry or dialogue (Dolinski et al., 2001; 2005) is more beneficial. In future studies, however, it would be tempting to directly address this issue. Such an experimental schema would be 2 (mimicry – yes vs. no) x 2 (dialogue – yes vs. no). With such a design, these techniques of social influence could be compared. THE ECHO EFFECT 26 The relationship between mimicry and positive mood also warrants further exploration. The mimickee may not only like the mimicker, but also, as a result of mimicry, feel better. Thusly, the mimickee might perceive herself or himself as more important and appreciated on the basis of the degree of imitation performed by the mimicker (Cheng & Chartrand, 2003). This, in turn, may result in an improved mood (Stel et al., 2008; van Baaren et al., 2004). Indeed, in the literature there are many studies showing that positive mood is responsible for making people more generous and eager to engage in prosocial behaviors, especially when this action does not incur high costs (a lot of time, a serious amount of money, etc…; Miller, 2009). Thus, it would be interesting to consider which mechanism, liking or positive mood, is responsible for verbal mimicry-compliance relationship. As van Baaren et al., (2004) has shown, the mimickee was more willing to help the mimicker than to help a third person, who was not involved in the interaction. This pattern of results seems to support a liking mechanism (against a mood mechanism). On the other hand, Stel et al., (2008) has shown that people mimicked more when a positive mood was elicited, and as a result engaged in helping behaviors more frequently, thereby supporting a mood explanation. Hence, it is still uncertain however, whether a similar pattern of results would be observed under conditions of the echo effect. Conclusion Data presented here clearly show that the echo effect is an effective and robust tool for influencing the tendency of others to engage in prosocial behaviors in comparison with non-mimicry (both no response and short statement), and dialogue conditions. Hence, the current experiment directly addressed concerns and ambiguities from previous verbal THE ECHO EFFECT 27 mimicry research and at the same time offers clear evidence that the mimicry-altruism effect is a real and robust phenomenon. THE ECHO EFFECT 28 Acknowledgments Special thanks to the editor and reviewers for their helpful feedback on previous drafts of this paper. Declaration of Conflict Interests The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding This research was supported by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education (644/MOB/2011/0) and the Polish National Science Centre (2011/03/B/HS6/05084). Notes 1. This experiment was able to be held in this typically guarded and high-security location because the currency exchange office cashier is a student in the University of Social Sciences and Humanities. Though naïve to the goals of the experiment, he agreed to play the role of confederate and was trained to interact with customers in that role as defined by each of the experimental and control conditions. The experiment was conducted during one of his normal work days with the consent of the currency exchange office management. 2. Polish intonation is extremely difficult for foreigners to master (even for those living in Poland for many years) and it is easy for native speakers to detect the difference between people who are not native speakers, and those who are. The confederate is a native Polish speaker and is quite adept at discerning this difference. He was THE ECHO EFFECT 29 specifically instructed only to select participants who he was 100% confident were native Poles. 3. Though, this may not be as easy as it seems. The previously described research by van Baaren et al. (2003) and Jacob et al. (2011) also did not include recorded or transcribed exchanges between the experimental participants and confederates, nor was this done in other studies investigating nonverbal mimicry (e.g., Chartrand & Bargh, 1999, Experiment 2). In contrast, our four experimental conditions were strictly controlled. It may be that public privacy, in such cases, trumps experimental design, and there may be no good solution for overcoming such a formidable obstacle. Being mindful of the fact that the goal of the current research was to conduct a study in a location where the request for the donation was not a part of the typical behavioral script, this location was selected, and the experiment was conducted with the full understanding that limitations on recording the interaction would be a consequence. THE ECHO EFFECT 30 References Cappella, J. N., & Panalp, S. (1981). Talk and silence sequences in informal conversations III: Interspeaker influence. Human Communication Research, 7, 117–132. Chartrand, T., & Bargh, J. (1999). The chameleon effect: the perception-behavior link and social interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 893–910. Chartrand, T. L., & Lakin, J. L. (2013). The antecedents and consequences of human behavioral mimicry. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 285–308. Cheng, C. M., & Chartrand, T. L. (2003). Self-monitoring without awareness: Using mimicry as a nonconscious affiliation strategy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 1170–1179. Dijksterhuis, A., Aarts, H., Bargh, J. A., & van Knippenberg, A. (2000). On the relation between associative strength and automatic behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 36, 531–544. Dolinska, B., & Dolinski, D. (2006). To command or to ask? Gender effectiveness of “though” vs. “soft” compliance-gaining strategies. Social Influence, 1, 48-57. Dolinski, D., Grzyb, T., Olejnik, J., Prusakowski, S., & Urban, K. (2005). Let’s dialogue about penny: Effectiveness of dialogue involvement and legitimizing paltry contribution techniques. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 35, 1150–1170. Dolinski, D., Nawrat, M., & Rudak, I. (2001). Dialogue involvement as a social influence technique. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 1395–1406. Fischer-Lokou, J., Martin, A., Guéguen, N., & Lamy, L. (2011). Mimicry and propagation of prosocial behavior in a natural setting. Psychological Reports, 108, 599-605. THE ECHO EFFECT 31 Fukuyama, H., & Myowa-Yamakoshi, M. (2013). Fourteen-month-old infants copy an action style accompanied by social-emotional cues. Infant Behavior and Development, 36, 609–617. doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2013.06.005 Garrod, S., & Pickering, M. J. (2009). Joint action, interactive alignment, and dialog. Topics in Cognitive Science, 1, 292–304. Giles, H., (1973). Accent mobility: A model and some data. Anthropological Linguistics, 15, 87-105. Giles, H., & Powesland, P. F. (1975). Speech style and social evaluation. London: Academic Press. Giles, H., Taylor, D. M., & Bourhis, R. (1973). Towards a theory of interpersonal accommodation through language: Some Canadian data. Language in Society, 2, 177–192. Goldinger, S. D. (1998). Echoes of echoes? An episodic theory of lexical access. Psychological Review, 105, 251–79. Goode, J., & Robinson, J. D. (2013). Linguistic synchrony in parasocial interaction. Communication Studies, 64, 453–466. doi: 10.1080/10510974.2013.773923 Guéguen, N. (2009). Mimicry and seduction: An evaluation in a courtship context. Social Influence, 4, 249–255. Guéguen, N., Martin, A., & Meineri, S. (2011). Mimicry and helping behavior: An evaluation of mimicry on explicit helping request. The Journal of Social Psychology, 151, 1-4. THE ECHO EFFECT 32 Guerrero, M. C. de, & Commander, M. (2013). Shadow-reading: Affordances for imitation in the language classroom. Language Teaching Research. doi:10.1177/1362168813494125 Ireland, M. E., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2010). Language style matching in writing: Synchrony in essays, correspondence, and poetry. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99, 549–571. Jacob, C., Guéguen, N., Martin, A., & Boulbry, G. (2011). Retail salespeople’s mimicry of customers: Effects on consumer behavior. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 18, 381–388. Kirschner, S., & Tomasello, M. (2010). Joint music making promotes prosocial behavior in 4-year-old children. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31, 354–364. Lakin, J. L., & Chartrand, T. L. (2003). Using nonconscious behavioral mimicry to create affiliation and rapport. Psychological Science, 14, 334–339. Lakin, J. L., Jefferis, V. E., Cheng, C. M., & Chartrand, T. L. (2003). The chameleon effect as social glue: Evidence for the evolutionary significance of nonconscious mimicry. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 27, 145-162. Macrae, C. N., Duffy, O. K., Miles, L. K., & Lawrence, J. (2008). A case of hand waving: Action synchrony and person perception. Cognition, 109, 152–156. Mantell, J. T., & Pfordresher, P. Q. (2013). Vocal imitation of song and speech. Cognition, 127, 177-202. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2012.12.008 THE ECHO EFFECT 33 Maddux, W. W., Mullen, E., & Galinsky, A. D. (2008). Chameleons bake bigger pies and take bigger pieces: Strategic behavioral mimicry facilitates negotiation outcomes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44, 461–468. Miller, C. (2009). Social psychology, mood, and helping: Mixed results to virtue ethics. Journal of Ethics, 13, 145-173. Müller, B. C. N., Maaskant, A., van Baaren, R., & Dijsterhuis, A. (2012). Prosocial consequences of imitation, Psychological Reports,110, 891-898. Neumann, R., & Strack, F. (2000). “Mood contagion”: The automatic transfer of mood between persons. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 211–223. Pickering, M. J., & Garrod, S. (2004). Toward a mechanistic psychology of dialogue. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 27, 169-189. Prinz, W. (1990). A common coding approach to perception and action. In O. Neumann & W. Prinz (Eds.), Relationships between perception and action (pp. 167- 201). Berlin: Springer-Verlag. Rind, B., & Benjamin, D. (1994). Effects of public image concerns and self-image on compliance. Journal of Social Psychology, 134, 19-25. Rind, B., & Bordia, P. (1995). Effect of servers ‘‘Thank you’’ and personalization on restaurant tipping. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 25, 745–751. Sagi, A., & Hoffman, M. L. (1976). Empathic distress in the newborn. Developmental Psychology, 12, 175–176. THE ECHO EFFECT 34 Shepard, C. A., Giles, H., & Le Poire, B. A. (2001). Communication accommodation theory. In: W. P. Robinson, & H. Giles (Eds.) The new handbook of language and social psychology (pp. 33-56.). Chichester: Wiley. Simner, M. L. (1971). Newborn’s response to the cry of another infant. Developmental Psychology, 5, 136–150. Stel, M., van Baaren, R., & Vonk R. (2008). Effects of mimicking: acting prosocially by being emotionally moved. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38, 965-976. Stel, M., & Vonk, R. (2010). Mimicry in social interaction: Benefits for mimickers, mimickees, and their interaction. British Journal of Psychology, 101, 311–323. Swaab, R. I., Maddux, W. W., & Sinaceur, M. (2011). Early words that work: When and how virtual linguistic mimicry facilitates negotiation outcomes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 616–621. Tanner, R. J., Ferraro, R., Chartrand, T. L., Bettman, J. R., & van Baaren, R. (2008). Of chameleons and consumption: The impact of mimicry on choice and preferences. Journal of Consumer Research, 34, 754–766. van Baaren, R. B., Holland, R. W., Kawakami, K., & van Knippenberg, A. (2004). Mimicry and prosocial behavior. Psychological Science, 15, 71–74. van Baaren, R. B., Holland, R. W., Steenaert, B., & van Knippenberg, A. (2003). Mimicry for money: Behavioral consequences of imitation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 39, 393–398. THE ECHO EFFECT 35 van Leeuwen, M. L., Veling, H., van Baaren, R. B., & Dijksterhuis, A. (2009). The influence of facial attractiveness on imitation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 1295–1298. Webb, J. T. (1969). Subject speech rates as a function of interviewer behavior. Language and Speech, 12, 54–67. Wiltermuth, S. S., & Heath, C. (2009). Synchrony and cooperation. Psychological Science, 20, 1–5. Xavier, J., Tilmont, E., & Bonnot, O. (2013). Children’s synchrony and rhythmicity in imitation of peers: Toward a developmental model of empathy. Journal of Physiology - Paris. doi: 10.1016/j.physparis.2013.03.012 THE ECHO EFFECT 36 Authors Biographies Wojciech Kulesza (PhD, University of Social Sciences and Humanities) is currently a visiting professor at Florida Atlantic University and has been employed at the University of Social Sciences and Humanities. His research interest is focused on the mimicry phenomenon and interpersonal coordination. In 2012 he published a chapter with Robin R. Vallacher and Andrzej Nowak titled “Interpersonal fluency: Toward a model of coordination and affect in social relations.” Dariusz Dolinski (PhD Warsaw University) is a full professor at the University of Social Sciences and Humanities, working in the area of social influence. His research program has investigated social influence techniques (e.g.,: fear-then-relief procedure - Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, foot-in-the-door phenomenon - Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, dialogue involvement technique - Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, touch and compliance - Journal of Nonverbal Behavior). Avia Huisman (PhD Candidate at Florida Atlantic University) holds the position of Outreach Coordinator for the College of Science at Marshall University. Her research interests include visual perception, interpersonal interactions, environmental communication, and determining factors that influence pro-environmental behavior. Robert Majewski (MA). His research interest is focused on the chameleon effect.