ADHD and the effects of dietary/food additives on children

advertisement

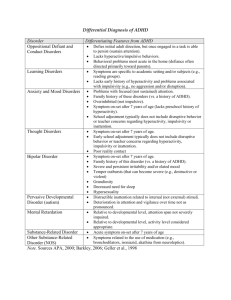

ADHD and the effects of dietary/food additives on children Angela Eastburn February 23, 2007 Advisor: Dr. Boissonneault, What is ADHD Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), aka Hyperkinesis, is the most commonly diagnosed behavioral disorder of childhood It is estimated to affect between 3% and 5% of schoolaged children The key symptoms of ADHD include inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity These behaviors usually appear before age 7, and affect boys two to three times more often than girls Symptoms are often so significant that they can interfere with daily life DSM-IV Criteria for ADHD I. Either A or B: Six or more of the following symptoms of inattention have been present for at least 6 months to a point that is disruptive and inappropriate for developmental level: Inattention Often does not give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, work, or other activities. Often has trouble keeping attention on tasks or play activities. Often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly. Often does not follow instructions and fails to finish schoolwork, chores, or duties in the workplace (not due to oppositional behavior or failure to understand instructions). Often has trouble organizing activities. Often avoids, dislikes, or doesn't want to do things that take a lot of mental effort for a long period of time (such as schoolwork or homework). Often loses things needed for tasks and activities (e.g. toys, school assignments, pencils, books, or tools). Is often easily distracted. Is often forgetful in daily activities. A. B. Six or more of the following symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity have been present for at least 6 months to an extent that is disruptive and inappropriate for developmental level: Hyperactivity • Often fidgets with hands or feet or squirms in seat. • Often gets up from seat when remaining in seat is expected. • Often runs about or climbs when and where it is not appropriate (adolescents or adults may feel very restless). • Often has trouble playing or enjoying leisure activities quietly. • Is often "on the go" or often acts as if "driven by a motor". • Often talks excessively. Impulsivity •Often blurts out answers before questions have been finished. •Often has trouble waiting one's turn. •Often interrupts or intrudes on others (e.g., butts into conversations or games). Some symptoms that cause impairment were present before age 7 years. Some impairment from the symptoms is present in two or more settings (e.g. at school/work and at home). There must be clear evidence of significant impairment in social, school, or work functioning. The symptoms do not happen only during the course of a Pervasive Developmental Disorder, Schizophrenia, or other Psychotic Disorder. The symptoms are not better accounted for by another mental disorder (e.g. Mood Disorder, Anxiety Disorder, Dissociative Disorder, or a Personality Disorder). DSM IV Criteria Continued I. II. III. IV. Some symptoms that cause impairment were present before age 7 years. Some impairment from the symptoms is present in two or more settings (e.g. at school/work and at home). There must be clear evidence of significant impairment in social, school, or work functioning. The symptoms do not happen only during the course of a Pervasive Developmental Disorder, Schizophrenia, or other Psychotic Disorder. The symptoms are not better accounted for by another mental disorder (e.g. Mood Disorder, Anxiety Disorder, Dissociative Disorder, or a Personality Disorder). Based on these criteria, three types of ADHD have been identified: ADHD DSM IV Subtypes (1) Predominantly Inattentive (2) Predominantly Hyperactive/Impulsive (3) a Combination of both. The most common of the three subtypes is the Combined Type Theorized Causes of ADHD The exact cause of ADHD is unknown Common theories include genetic neurobiological causes, child-rearing methods, environmental agents (i.e. cigarette smoke), and dietary allergies from common food additives. Common Allopathic Treatments Medication, behavioral therapy, emotional counseling, and support groups are common modalities of treatment in ADHD Gold Standard: stimulant drugs The use of stimulants have been shown to decreases the severity of the 3 key symptoms of ADHD These drugs have been deemed safe for children, and are shown to have relatively low incidence of abuse and dependency The most commonly used stimulants in the treatment of ADHD are Methylphenidate (Ritalin), Adderall, and Concerta. The Downside of Stimulant Therapy Stimulants do not give the effects of a “high” however, many children report feeling “funny” or “different” Each child will react differently to each medication, and one in ten will receive no benefit from the addition of stimulants. Side effects are usually mild but appear to be related to medication dosages Common side effects include: irritability, anxiety, insomnia, decreased appetite, mild head and stomach aches The Feingold Diet Pediatric allergist Benjamin F. Feingold of the KaiserPermanente Medical Center in San Francisco In1973, Feingold addressed the American Medical Association with claims that a child’s allergies and behavioral issues could be alleviated when placed on his restrictive diet Feingold’s Research and Claims Feingold’s diet was originally intended to help children plagued with allergies (specifically acute urticaria or hives) that were unresponsive to previous drug interventions and treatments. In testing his allergy restrictive diet, he noticed that hyperactive test subjects also benefitted from the diet; the incidence of behavioral outbursts decreased dramatically (58-60%) Feingold’s research showed a direct correlation between the increasing use of artificial food additives and the increasing incidence of hyperkinesis and learning disabilities Feingold believed that the pharmacological characteristics of certain food additives acted as a suppressant on a child’s ability to learn, behave and function appropriately Feingold’s Research and Claims According to initial studies, Feingold noticed that children who had not previously responded well to medications (e.g. Ritalin) dramatically improved when subjected to a diet free of common food additives He also noted an ability to “turn on and off” behaviors with reintroduction of additives into the diet, further proving his hypothesis Feingold claimed that positive behavioral changes as a result of the K-P diet could be seen in as little as two to three days. The speed of improvement was said to depend upon the age of the subject (the younger the more rapid), adherence to the diet, and time needed for clearance of pharmaceuticals from the system At the end of five clinical studies, Feingold’s team found that 50% of patients had a likelihood of full response, and 75% could be completely removed from drug management Feingold’s diet consists of eliminating the following food additives: Artificial (synthetic) coloring (FD&C and D&C colors) Artificial (synthetic) flavoring (e.g. Glutamic acid salts, MSG) Aspartame (Nutrasweet, and other artificial sweeteners) Artificial (synthetic) preservatives BHA, BHT, TBHQ These additives were specifically chosen to be eliminated because many are synthetic substances made from petroleum refining process by-products, and were reported to possess an inherent potential to produce adverse effects Other Common Dietary Restrictions High Fructose Corn Syrup Calcium Propionate Nitrates MSG Elimination of Salicylates The K-P diet, also restricts certain salicylate containing foods. Salicylate can mock the action of aspirin, and are thought to cause adverse reactions in allergy sensitive, and hyperkinetic patients. Common salicylate containing foods included berries, currants, apples, oranges, tomatoes, cucumbers, coffee, and almonds Problems and Controversy The miraculous changes in ADHD children came at the high price of a very strict, labor-intensive diet. Locating, preparing, and affording foods free of coloring, flavorings, and preservatives presented parents with quite a daunting task Many common food items were eliminated, making the diet very hard to maintain. Many proponents of the K-P diet claim the hassle was well worth the time and effort, and saw many significant improvement in hyperkinetic patients. Skeptical critics on the other side of the fence claimed followers simply fabricated positive results for lack of better or more effective treatment options. Numerous studies were never able to replicate Feingold’s 58-60% improvement statistic Testing the Feingold Hypothesis The first researcher to test Feingold’s hypothesis was Dr. Keith Conners of the Children’s Hospital National Medical Center in Washington D.C. According to Conners, the Feingold studies contained no true scientific methodologies in selection, inception, or data collection, were uncontrolled, unblinded, and utilized no objective rating scales As a result, Conners meticulously controlled and documented his clinical trials and data Conners Experiment #1: control diet vs. the K-P diet in15 children determined to be hyperkinetic (based on interviews by clinical psychologists, testings, and physical and neurological exams, and rating scales outlined by the NIMH standards of 1973). Conners Clinical and Observational Results Research data indicated that both teachers and parents reported a decrease in hyperactivity when on the K-P diet vs. baseline activity. However, it was only teachers that noted a positive reaction to the K-P diet over the control diet. For Feingold’s hypothesis to be true, behavioral differences should be observed in both baseline and control. Connor concluded that hyperactivity may be reduced in children with ADHD when the child genuinely possesses an allergy to additives He goes on to state that “significant data remained to be collected before a recommendation could be given for approval of the diet.” National Advisory Committee on Hyperkinesis and Food Additives 1. 2. 3. 4. This committee was specifically formed to evaluate the validity of Feingold’s clinical findings Upon their review, they too concluded that Feingold had not sufficiently proven his hypothesis and highlighted several other significant shortcomings in his research: The high number of reported favorable responses to placebo The potential changes in family dynamic due to the strict regiment of the diet Possible coercion of positive results from researchers and Feingold himself. Lastly, due to its highly restrictive guidelines, the K-P diet may have also substantially reduced essential nutrient and vitamin concentrations, in turn contributing to additional behavioral changes Feingold’s Advocates The biggest advocates for the KP diet seem to lie in parents of children with ADHD and hyperactivity. Despite many negative research publications, like the ones mentioned previously, many parents swear by the regimen and are able to maintain it for life. Parents are quoted as saying that they have a completely different and manageable child after inception of the K-P restrictive diet. A study conducted by Dr. P.S. Cook in 1976 documented that 10 out of 15 parents enrolled in clinical trials saw substantial behavioral improvements, and drastic relapse (in poor behavior) upon dietary infractions Feingold’s Advocates A study by Dr. F. Levy in 1978, Hyperkinesis and diet: a double-blind crossover trial with a tartrazine challenge, also documented statistically noteworthy improvements when he eliminated tartrazine, one of Feingold’s hypothesized triggers, from patient’s diets. Mothers of study participants in this study indicated a 25% reduction in adverse behaviors when maintaining the diet free of the artificial food coloring A second study of tartrazine and hyperkinesis was recently conducted by Dr. Katherine S. Rowe in 1994. Test subjects in Rowe’s experiments showed signs of increased irritability, restlessness, and sleep interruptions when challenged with tartrazine, again supporting some of Feingold’s initial claims More of Feingold’s Advocates In 2004 Dr. B. Bateman conducted a double-blind, placebo controlled coloring and preservative challenge in a large sample of preschoolers. In his population of 3 year old ADHD suffers, parents noticed unpleasant behavioral effects when challenged with artificial food colorings and benzoate preservatives. Again, this behavioral improvement phenomenon could not be detected in clinical data and assessments Regardless, Bateman does suggest the findings are indeed significant and warrant further investigation What does this mean for the patient and the PA? Treatment options? Medication vs. Diet Providers should be well versed on the benefits and shortcomings of both pharmacological and dietary therapies PCP should be aware of all attempted therapies and outcomes whether beneficial or not We need to help families realize that every child will react differently to different treatment modalities Discuss all options: Is an elimination diet a viable option for the family and the child? Who will participate? When will the diet be implemented? Who will prepare meals and monitor changes in behaviors? Be aware of personal judgements and biases Conclusions The common denominator: a healthy diet, whether restrictive of artificial additives or not, is beneficial to the health and wellbeing of every child Feingold’s overarching goal was to develop a dietary plan that assisted families in their battle with ADHD. He accomplished this goal by providing insightful ideas and hypotheses that sparked interest into treatments for this sometimes debilitating disorder. As a result he served as an advocate for hyperkinetic children and families. Although not all of his theories were proven clinically relevant or reproducible, they do offer a solution to many families that had previously been unsuccessful with behavior and pharmaceutical treatments. References American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical practice guideline: diagnosis and evaluation of the child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2000;105(5):1158-1170. American Psychiatric Association. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994:78-85. Baumgaertel A. Alternative and controversial treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatr Clin of North Am. 1999;46(5):977-992. Boris M, Mandel F. Foods and additives are common causes of the attention deficit hyperactive disorder in children. Ann Allergy. 1994;72:462-468. Breakey J. The role of diet and behavior in childhood. J Paediatr Child Health. 1997; 33:190-194. Carter CM, Urbanowicz M, Hemsley R, et al. Effects of a few food diet in attention deficit disorder. Arch Dis Child. 1993;69:564-568. Food and Drug Administration. Medwatch: the FDA safety information and adverse event reporting program. Cylert (pemoline). Accessed at http://www.fda.gov/medwatch/safety/1999/cylert19.htm on November 16, 2001. Lee S. Biofeedback as a treatment for childhood hyperactivity: a critical review of the literature. Psychol Rep. 1991;68:163-192. Linden M, Habib T, Rodojevic V. A controlled study of the effects of EEG biofeedback on cognition and behavior of children with attention deficit disorder and learning disabilities. Biofeedback Self Regul. 1996;21(1):35-49. Mitchell EA, Aman MG, Turbott SH, Manku M. Clinical characteristics and serum essential fatty acid levels in hyperactive children. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1987;26:406-411. National Institute of Mental Health. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Accessed at: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/publicat/adhd.cfm on November 9, 2001. National Institutes of Health. Diagnosis and treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement. November 16-18, 1998. Accessed at: http://odp.od.nih.gov/consensus/cons/110/110_statement.htm on November 9, 2001. Richardson AJ, Puri BK. The potential role of fatty acids in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2000;63(1/2):79-87. Rowe KS, Rowe KJ. Synthetic food coloring and behavior: a dose response effect in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, repeated measures study. J Pediatr. 1994;125:691-698. problems. Physiol Behav. 1996;59(4/5):915-920. Stevens LJ, Zentall SS, Deck JL, et al. Essential fatty acid metabolism in boys with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;62:761-768.