D4 11_for internal r..

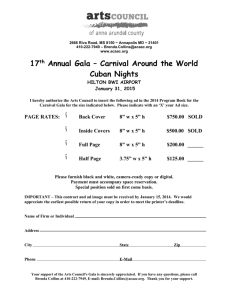

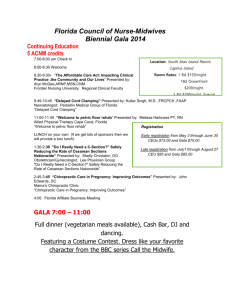

advertisement