ISS research paper template - Erasmus University Thesis Repository

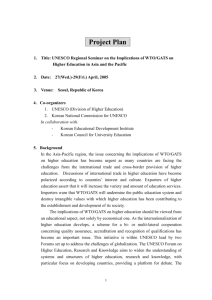

advertisement