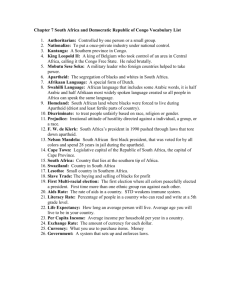

powerpoint - School of English

advertisement

Ideologies of language

and linguistic conflict in

colonial and postcolonial

South Africa

{

orman.jon@gmail.com

Language in Africa: some

‘facts’

Africa is a continent of high linguistic diversity with more than 2,000

recorded language names (and more than 500 in Nigeria alone)

6 major language families, many languages remain unclassified

High levels of individual oral multilingualism, no linguistically

homogenous states

Sixteen of Africa’s shared cross-border languages have > 150 million

speakers.

most African languages remain unwritten

Low levels of literacy, (highest Seychelles 91%, Zimbabwe 85%,

lowest Burkina Faso 12.8%). Often significant differences in literacy

rates between men and women

Around 60% primary school attendance rates on continent as a whole

(UNICEF). South Africa = 87% (2009).

Linguistic diversity in Africa

Official languages in

Africa

Some key themes:

-

Linguistic history of South Africa characterised by contact, conflict,

complexity & inequality

-

Social identities have generally emerged through contact between

groups within a framework of highly unequal power relations

-

SA has witnessed the ‘invention’ of languages based on

Eurocentric ideologies of separate languages

- Throughout South Africa’s colonial and postcolonial history,

language policy & planning has been a central feature of

successive governments’ attempts to construct and manipulate

social identities - although rarely very successfully

4 distinct historical eras

Initial period of Dutch colonisation of the Cape (1652-1806)

British colonial period (1806-1910) & Union of South Africa (19101948)

Apartheid (1948-1994)

The post-apartheid era (1994 - )

Dutch colonial period

Dutch East India Company (VOC) arrived at Cape in 1652 to set

up supply station, small early population speaking

predominantly coastal varieties of Dutch

Various language contact situations:

- European settlers and Khoikhoi, slaves from Indian

subcontinent, Dutch East Indies, West Africa, later Madagascar

and East Africa

- traces of these contact situations in present-day Afrikaans, e.g.

Baie, pisang, gogga, dagga, blatjang, sjambok etc.

- between European settlers (Dutch, French, German etc.),

-

Dutch establishes itself as dominant language in various forms, dialect

levelling, including learner (L2), pidgin & creole varieties,

vernacularisation > Cape Dutch/Afrikaans

-

However, never any question of shared identity across racial boundaries

– resistance to gelykstelling

- language shift from other European languages,

the VOC demanded that French speakers ‘be taught our language and

morals, and be integrated within the Dutch nation’

- integration of French speakers into Dutch identity community possible

because they were European & Christian

- large scale destruction of KhoiKhoi social order due to small pox

epidemics

- linguistic assimilation of slaves

- little in the way of official policy regarding language

British colonial language

policy

British seize Cape of Good Hope from Dutch in 1806

Aim of establishing that was ‘British in character as well as name’ =

imposition of British cultural practices on the Dutch-speaking population – a

policy of Anglicisation

“they were only a little over thirty thousand in number, and it seemed

absurd that such a small body of people should be permitted to perpetuate

ideas and customs that were not English in a country that had become part

of the British Empire.” (Malherbe, 1925:57)

denigration of Dutch/Afrikaans as a kombuistaal etc. – ‘a jargon

without literature, without scientific basis and without practical value

outside local confines’ (The Star, 1911)

‘The Afrikaans language is laughable because it lives in the kitchen, on the

street, in the canteens, in the houses of the uneducated’ (De Waal,

1939:268)

1822 – English made sole official language of Cape colony

‘Dutch should only be used to teach English and English to teach

everything else’

1828 – all court proceedings to be in English only

resistance to policy from Dutch/Afrikaans speakers, Afrikaners

set up private Dutch-medium schools, Doppers fought against

Anglicisation of religious life

origin of the taalstryd and the emergence of Afrikaner national

consciousness, belief in one-to-one link between language and

ethnic/national identity

W. Postma, Dutch Reformed Church Minister, 1910:

“Take away our language and we will become Englishmen”

Afrikaans emerges as a ‘core value’ of Afrikaner identity –

the failure of Anglicisation policy

Core values can be regarded as forming one of the most fundamental

components of a group’s culture. They generally represent the

heartland of the ideological system and act as identifying values which

are symbolic of the group and its membership. Rejection of core values

carries with it the threat of exclusion from the group. (Smolicz,

1981:75)

British colonial language policy

and the African population

-

sections of African population also target of linguistic/cultural

assimilation - Britain’s ‘civilising mission’

role of missionary schools and Anglicisation of the ‘mission elite’ - “the

tiny layer of black teachers, preachers, interpreters, clerks and other

professionals which the colonial system had necessarily given rise to”

“The scholarly missionaries educated a group of men and women with high

competence in English, a deep insight into the world of ideas and values and a

strong language loyalty to English”

-

English acquires prestige, as a key to black upward socio-economic

mobility, African languages not seen as appropriate for higher functions

In 1910, the African People’s Organisation (APO) encouraged

its members to:

“endeavour to perfect themselves in English - the

language which inspires the noblest thoughts of

freedom and liberty, the language that has the

finest literature on earth and is the most

universally useful of all languages. Let

everyone...drop the habit as far as possible, of

expressing themselves in the barbarous Cape

Dutch that is too often heard”

“The pursuit of Anglicisation was probably one of the greatest political

errors of South African history because it set in motion a chain of events

which continues to haunt education and language policy a hundred

years later.” (Kathleen Heugh, South African sociolinguist)

‘Black Englishmen’ also seen as an affront to the Afrikaner ideal

of racial and ethnocultural authenticity and a potential political

threat – to have a great influence on language ideology and

policy in the apartheid years

The invention of African

languages

British (and other European) colonial missionary linguists responsible

for identifying and naming many current South African ‘languages’, e.g.

isiXhosa, isiZulu

Wrote grammars, developed alphabets etc. with primary aim of

translating the bible in order to christianize the African population – not

unproblematic exercises

However, notion of discrete, countable, named ‘languages’ is a product

of 18th/19th century European nationalism, literate cultures

The idea of separate, object-like entities called languages was unknown

in African culture. ‘Languages’ not timeless, universal entities. Product

of ‘colonial imaginings’ and transplantation of Eurocentric ideologies

The naming of languages produced puzzling

questions such as ‘What languages do you

speak?’, as opposed to the typical African

question ‘Do you speak?’, which on its own

suggests that names of languages are not part of

the lexicon of speakers of these languages. This

indicates that language among lowly literate

African is conceptualised without positing the

existence of languages as spatially and ethnically

bounded entities, or without cutting up

language into different languages or different

parts such as verbs, nouns etc. (Makoni,

2011:683)

Does the hubristic colonial enterprise of naming and

inventing ‘languages’ where previously there were none

persist in modern-day linguistics?

Another problem in deciding how many languages there are in the

world arises from the fact that many have no special names. The

Sare people of the Sepik region of Papua New Guinea for example

call their language Sare, but this means simply ‘to speak or talk’.

The Gitksan people of British Columbia have no conventional

native name for their language which sets it apart from other

varieties such as Nisgha and Tsimshian. The Gitksan generally

refer to their own language as Sim’algax, “the real or true

language,” but the Nigsha and Tsimshian people do the same.

(Nettle and Romaine, 2000:27-28)

Notion of individual, separate languages often irrelevant to

a people’s self-conceptualisation of their linguistic

experience

Can the linguist tell people what language they speak?

The modern South African state

THE UNION OF SOUTH AFRICA (1910-1948)

Boer states of OFS & Transvaal join British Cape Colony & Natal

Dutch acquires co-official status, Afrikaans becomes official

language in 1925 alongside English, bilingual state

British persist with policy of Anglicisation, still an English-only

ideology

“English-speaking South Africa never took the matter seriously.

Bilingualism was regarded as nothing more than a polite gesture

towards the other section – neither more nor less. The average Englishspeaking South African was inclined to regard every political

recognition of the Dutch language as a menace to the interests of his

own race.’ (from the editor of Volksstem, 1929)

Apartheid language

policy

-

Official policy of ‘separate development’ began 1948, marks the start of the

high period of ethno-racial, white Afrikaner, linguistic nationalism

-

Strict division of society along racial and linguistic lines. Population divided

into 4 racial groups: White, Black, Coloured and Asian.

-

Afrikaner linguistic nationalism: language seen as essence of divinely

ordained nationhood

-

God willed separate nations and peoples, and He gave to each separate nation and

people its special vocation, task and gifts.

We will have nothing to do with a mixture of languages, of culture, of religion or of

race’ (Institute for Christian National Education, 1948).

Semiotic landscape of Apartheid

Apartheid education

- Cornerstone of Apartheid language policy: mother-tongue education

(moedertaalonderwys)

- For whites, education in one of the two official state languages: English

or Standard Afrikaans – Algemeen Beskaafd Afrikaans

For the African population, mother-tongue education had far more

negative implications

Apartheid philosophy views black population as consisting of many

different separate (potential) nations , each supposedly defined by

language

Bantu Education Act 1953 – compulsory mother-tongue schooling for

first 8 years of primary education, most black students did not continue

into secondary school

Closure of many English-medium mission schools

Aim to prevent black people from acquiring competence in

English, achieving social mobility uniting against apartheid

system

Mother-tongue schooling for blacks was employed

[. . .] to support the social and educational goals of

apartheid. The apartheid regime used such

programs to reinforce ethnic and tribal identity

among black schoolchildren, seeking to ‘divide and

conquer’ by encouraging ethnolinguistic divisions

within the black community. (Reagan, 2001:55)

Apartheid invention of languages

E.g. Northern Sotho language artificially distinguished from

Setswana for administrative and political purposes

Mother-tongue is a highly problematic concept in the South

African context. Relations between language and identity are far

more complex.

My father’s home language was Swazi, and my mother’s home language

was Tswana. But as I grew up in a Zulu-speaking area we used mainly

Zulu and Swazi at home. But from my mother’s side I also learnt Tswana

well. In my high school I also came into contact with lots of Sotho and

Tsonga students so I can speak these two languages well. And of course I

know English and Afrikaans. With my friends I also use Tsotsitaal. (cited

in Orman, 2008:88)

Mother-tongue education as a policy of social control and

division

‘The language policy of the apartheid regime explicitly fomented

fragmentation based on parochial ethnolinguistic identity. However,

instead of provoking linguistic tribalism, the apartheid policy merely

incited Blacks to rally around global English as the language of

resistance and protest [. . . ]Blacks saw English as the tool to combat

divisive Bantu education and the imposition of Afrikaans.

- English increasingly becomes a symbol of resistance to

apartheid, especially following Soweto uprising 1976.

Afrikaans seen as the ‘language of the oppressor.’

- Failure of apartheid language/identity planning

\

Language protests Soweto 1976

Post-apartheid language

policy (post 1994)

Change 2 to 11 official languages – ideology or pragmatism?

Official policy of ‘equitable multilingualism’, pluralism

Large increase in language planning bodies and activities,

e.g. PANSALB.

Promotion of nation-building based on multilingualism and

linguistic diversity, philosophy of unity in diversity – no

single national language, individual multilingualism

rejection of Eurocentric models of language and nation,

ideology of ‘one language, one nation’

But, the reality?

A large language policy-practice ‘gap’

‘The more languages, the more English’

Increasing English monolingualism in public life, dominance of elite

language practices > linguistic inequality

Declining position of Afrikaans as a public language, Anglicisation of

historic Afrikaans-medium universities, changing of Afrikaans place

names. E.g Pretroria-Tshwane, Bloemfontein-Mangaung

Language still a source of conflict, especially in relation to Afrikaans,

many protests

African languages remain highly marginalised, rising inequality

In summary

Throughout its colonial and postcolonial history, SA has been

a site of linguistic contact linguistic conflict

Linguistic divisions often correlated with racial divisions and

social inequality

Attempts to plan identities through language

policy/planning have generally been failures and generated

identities of resistance

The linguistic complexity of diverse societies such as SA

cannot be captured adequately through a Eurocentric notion

of individual, separate languages and easily identifiable

‘native’ speakers – these are highly problematic concepts

Any questions?