Long Term Care Restructuring in New York State

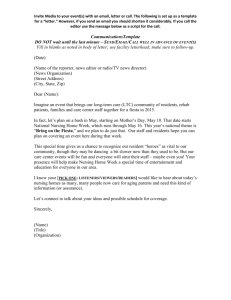

advertisement