Psychological and Ethical Egoism

advertisement

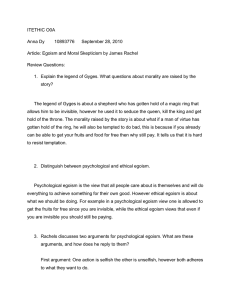

Psychological and Ethical Egoism How do we decide what to do? How should we decide? Joel Feinberg (1926-2004) Social and political philosopher at University of Arizona Wrote on a wide range of moral issues (capital punishment, treatment of the mentally ill, environmental ethics). Psychological Egoism Human beings always act in pursuit of (what they see as) their self-interest. Psychological egoism is purely descriptive –it says this is what humans do, not that it’s what they should do. But it’s a very strong claim– it isn’t that people are often, or even typically selfish. It holds that people are always being selfish, no matter what they do. Selfish? This is obviously some strange usage of the word ‘selfish’ that I wasn’t previously aware of. (apologies to D. Adams) For example: Bentham’s psychological hedonistic egoism: all voluntary behaviour is motivated by a desire for one’s own ‘pleasure’. Or perhaps it’s not ‘pleasure’ that motivates us, but happiness. Or some kind of personal well-being (our own idea of what would be good for us) Why suppose this strange view at all? After all, we enjoy it when we get what we want– so maybe all we really want is the enjoyment… Further, I can only act on my motives, pursuing my ends and desires, so surely I’m always acting selfishly. We know people can deceive themselves into thinking they’re being generous when they’re really serving their own interests. We teach morality by reward and punishment, so maybe that’s the only reason people act morally. The charge against PE This is vague, armchair ‘science’, not real (empirical) psychology. How testable is the claim that we are always (really) selfish? Think of the behaviour we have to explain under this assumption: A mother gives up her life in defense of her child. A busy man distributes food and clothing to homeless people at night. A soldier throws himself on a hand grenade to save his comrades. My motives needn’t be selfish Sure, my motives are my own. But that doesn’t mean (isn’t equivalent to their being) selfish. All voluntary action emerges from the agent’s motives. These motives belong to the agent, in some sense. But not all motives are selfish, in the sense of serving only the agent’s own interests. Pleasure and motive Further, even if we always enjoy or take pleasure in the results when our voluntary actions succeed (and it’s really hard to say this for the soldier case), this wouldn’t show that the motive for the action was to experience that enjoyment or pleasure. James: the fact that coal is always burned on a transatlantic voyage doesn’t show that burning coal is the purpose of every voyage. The Lincoln story: what exactly does it show, according to Feinberg? Revenge and malevolence Studies show that people are quite prepared to sacrifice their own interests to punish others who have refused to cooperate with them. This has been noted by many– these actions, too, cannot be plausibly explained in terms of purely selfish motives. (Why would you ‘enjoy’ such a sacrifice if you weren’t bent on harming this other person from the outset, rather than on serving your own interests?) Seeking pleasure or happiness alone? What’s puzzling about the ‘pursuit of happiness’? Consider Feinberg’s “Jones”: No particular desires or enjoyments. But desperately wants to be ‘happy’. Is there any hope for such a person? Note the parallel here to the Lincoln example: we can’t take pleasure in things unless we already value those things themselves. Morality vs. Reward and Punishment It’s true that we teach morality, in part, by the use of reward and punishment. But it doesn’t follow that no-one behaves morally except out of desire for reward or fear of punishment. In fact, studies show that too much emphasis on rewards (rather than on an activity and its intrinsic goals) can undermine performance. And a ‘moral’ person who is only moral in this way is hardly trustworthy… Against Hedonism ‘Pleasure’ can mean either intrinsically enjoyable sensory experiences, or Something that arises from achieving goals or desires. The second kind of pleasure presupposes a real desire for something other than pleasure. Exclusive focus on the first kind of pleasure is rare (consider gourmets on a food tour, or an oenophile on a wine tour). It doesn’t dominate our aims and goals in general, and does a terrible job of explaining a lot of what we do. Pleasure as satisfaction If the hedonist’s claim is that it’s always only satisfaction we want, then we seem to be in even worse trouble. The question is, satisfaction of what? Our desires? Then what are our desires for? For satisfaction? Surely that’s too tight a circle! Alternative forms of egoism Could our motives always be self-regarding (and thus selfish) even if they aren’t always a desire for pleasure or happiness? What could show this? We need to know the status of the claim first: is it Analytic (a matter of meanings alone)? Or Synthetic (something that is true, but could be false)? Playing games with the distinction One way to produce strange, but philosophicalsounding assertions is to say things that are naturally understood to be empirical but false, but To defend them in ways that make it clear that they aren’t empirical at all, but instead ‘built into’ a nonstandard take on what the words involved mean, i.e. that (for you) they are analytic. Then it seems we’re engaged in a dispute over the meanings of words, not the way the world is. A use for ‘selfish’ Many words get their force from a contrast that they invoke. Selfish/unselfish is one example of such a contrast, as are good-bad, large-small,… If we lose the contrast, then we lose something important to their meanings. But when everything we do is said to be ‘selfish’, we’ve lost the contrast here. Reductio ad trivium If we re-define a word so that a superficially startling statement actually turns out to be tautologous, then we’ve reduced the statement to the (merely) trivial. Worse, in this case, as well as having made a trivial claim (on one way of reading it, that “all motivated actions are motivated”), the PE advocate has suppressed the correlative. Our assumption that the correlative remains is all that makes the claim seem non-trivial. Changing languages We could change our language to adopt the PE proposal. This involves accepting that all motivated actions are ‘selfish’, But we will still need to distinguish selfish actions of the kind we would discourage and regard as wrongful from those that we praise and encourage. The old distinction is still there, and we still need our language to recognize it, one way or the other. So in the end, the PE proposal is pointless. James Rachels (1941-2003) An ethicist with broad interests including applied ethics (euthanasia, the treatment of animals, crime and punishment), in ethical theory, and in the history of evolutionary thought. Famine Relief Millions of children die every year of hungerrelated illness (not to mention other, easilypreventable causes). We don’t do much about it (governments have repeated failed to meet their pledges to increase foreign aid, and often tie food aid to support for their own agricultural sectors). What should we do about it, if anything? “Common sense” vs. ethical egoism Common sense morality holds that we are required to ‘balance our interests against the interests of others’ Ethical egoism holds that we have no ‘natural’ duties towards others, i.e. none that we don’t explicitly incur by (voluntarily) making promises… This is pretty radical– and it has obvious implications for the opening question here. Three Arguments for ethical egoism 1. 2. 3. It’s for the best (the pursuit of our own selfish interests actually produces the best overall result for everyone). Ayn Rand: Only ethical egoism recognizes “the value of an individual life”, the ultimate value for each individual. Ethical egoism is the best explanation/ theoretical framework for the demands of common sense ethics. Bad arguments: Argument 1 is confused: it assumes that we aren’t EEists, and argues we should nevertheless act as if we were. Argument 2 works only by presenting a false dilemma. The real alternative (the common sense morality of balancing interests) never gets discussed. Argument 3 shows that an EEist should behave reasonably well, but that’s not enough to show that EEism is correct. Arguments against EEism 1. 2. 3. Baier’s conflict of interest argument: the point of ethics is to resolve conflicts of interest, but EEism cannot do this. Baier et al.’s contradiction argument. EEism leads to a contradictory result– by EE, you should always act to prevent someone from doing you harm, but sometimes, by EE, they should harm you, so you should not act to prevent them. The argument from relevant differences. Bad arguments? Rachels says argument 1 and 2 both make assumptions that an EEist would reject. What about argument 3 (Rachels says it’s the best one)? Does the lack of any relevant difference between the interests of different groups or individuals show that we can’t justify declaring that some matter to us but others don’t? What is the key point about morality that Rachels draws from argument 3?