The final Romanow Royal Commission report entitled

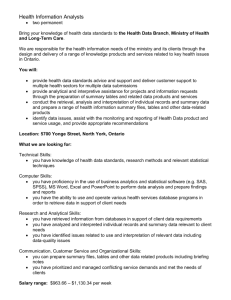

advertisement