Slides - Clinicians Channel

advertisement

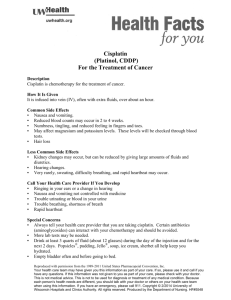

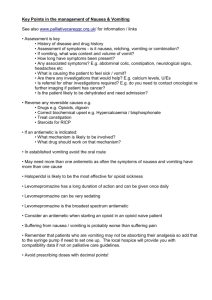

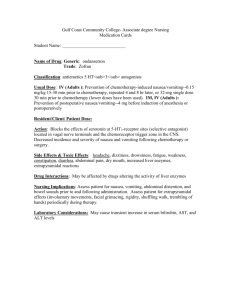

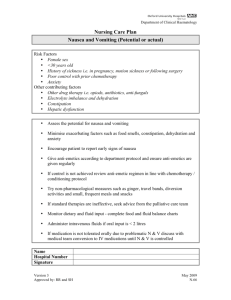

Looking at Breakthrough Nausea/Vomiting and Cancer-Related Pain The Cannabinoid Experience Vincent Maida, MD Assistant Professor University of Toronto Division of Palliative Medicine William Osler Health Centre Toronto, Ontario, Canada Incidence of Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting (CINV) and Pain in Cancer Patients Approximately 70%–80% of chemotherapy patients experience nausea and vomiting1 Patients rank nausea and vomiting as 2 of the most feared side effects of cancer treatment More than three quarters of cancer patients experience chronic pain during the course of their disease2 1. Wiser W, Berger A. Oncology. 2005;19:637. 2. Portenoy RK. Semin Oncol. 1995;22(suppl 3):112. Consequences of Unresolved CINV Adverse sequelae of nausea and vomiting in the cancer patient Serious metabolic derangements Nutritional depletion and anorexia Esophageal tears Wound dehiscence Deterioration of patients’ physical and mental status Degeneration of self-care and functional ability Discontinuation of therapy NCCN Practice Guidelines in Oncology–Version 1. 2007. Antiemesis, MS-1. CINV—Decreased Quality of Life FLIE Questionnaire HEC-FLIE > MEC-FLIE FLIE-nausea > FLIE-Vomiting P = .0097 There is a greater negative impact on QOL from nausea than there is from vomiting P = .0049 FLIE = Functional Living Index-Emesis; HEC = highly emetogenic chemotherapy; MEC = moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Bloechl-Daum, B, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4472. NCCN Practice Guidelines Prechemotherapy Emesis Prevention Highly emetogenic regimens – Day 1: aprepitant, dexamethasone, and a 5-HT3 antagonist +/- lorazepam – May be modified on days 2–4 Moderately emetogenic regimens – Day 1: dexamethasone and a 5-HT3 antagonist +/- lorazepam (aprepitant added with select moderately emetogenic regimens) – Modified on days 2–4 Low emetogenic regimens – Dexamethasone, proclorperazine, or metoclopramide +/- lorazepam NCCN Practice Guidelines in Oncology – Version 1. 2007. Antiemesis, MS-1. NCCN Practice Guidelines Postchemotherapy/Delayed Emesis Prevention Highly emetogenic regimens – Primary antiemetic regimen continued through period when delayed emesis may occur (ie, 2–3 days after chemotherapy cycle) Moderately emetogenic regimens – Dependent upon the antiemetic used before chemotherapy Palonosetron on day 1 only Aprepitant continued on days 2 and 3 +/- dexamethasone or lorazepam Dexamethasone or a 5-HT3 antagonist +/- lorazepam NCCN Practice Guidelines in Oncology – Version 1. 2007. Antiemesis, MS-1. NCCN Practice Guidelines Breakthrough Treatment Around-the-clock administration, rather than PRN dosing, should be considered Additional agents should be from a different drug class than initial therapy – Possibilities include: dopamine antagonists, metoclopramide, butyrophenones, cannabinoids, corticosteroids, or agents such as lorazepam Nabilone (cannabinoid) has recently been approved for nausea/vomiting in patients who have not responded to conventional antiemetics NCCN Practice Guidelines in Oncology – Version 1. 2007. Antiemesis, MS-1. Cannabinoids Botanical Endogenous Pharmaceutical Marijuana Anandamide Nabilone Hashish 2-AG Dronabinol PEA Delta-9-THC & cannabidiol Cannabinoid Receptors CB1—neuromodulation CB2—immunomodulation Basal ganglia Spleen Hippocampus Tonsil Cerebral cortex Mast cells Cerebellum Macrophages Spinal cord Lymphocytes Afferent nociceptors Microglia Kalant H. Pain Res Manag. 2001;6:80. Mechanism of Action of the Cannabinoids 5 EXOGENOUS Cannabinoid Therapy Presynaptic Neuron Inhibition of Neurotransmitter Release 1 Neurotransmitter (NT) from presynaptic neuron activates the postsynaptic neuron 2 Activated postsynaptic neuron releases endocannabinoids 3 Endogenous CB1 ligand diffuses back to and binds to the presynaptic CB1 receptor 4 CB1 receptor activates a G-protein, leading to inhibition of NT release 5 Nabilone is thought to activate CB1 receptors directly, mimicking the effects of endocannabinoids CB1 Receptor 4 1 Postsynaptic Neuron 2 Neurotransmitter Receptor Endogenous and Exogenous Cannabinoids Reduce Neuronal Signaling 3 Endogenous Cannabinoid Retrograde Signaling Adapted from Page 5 of Slatkin NE. J Support Oncol. 2007;5(suppl3):1. Reprinted with permission. Cannabinoids—Supportive Oncology Established roles – CINV Emerging roles – Analgesia – Spasmolysis – Anorexia-cachexia – Sedative – Antidepressant – Antineoplastic Causes of Nausea and Vomiting in Cancer Patients Gastric stasis Drugs – Opioids – Chemotherapy Biochemical – Hypercalcemia – Uremia Raised intracranial pressure Intestinal obstruction Pain Twycross R. Palliative Care. 3rd ed, Radcliffe Medical Press. Oxford:1999:114. Diverse Neurotransmitters Mediate Emesis Serotonin (5-HT3) Substance P (NK-1) Dopamine (D2) N+V REFLEX GABA Histamine Endorphins Acetylcholine Cannabinoids Drug classes FDA approved in CINV Adapted from Andrews PL, Naylor RJ, Joss RA. Supportive Care Cancer. 1998;6:197-203. Delayed CINV Is More Prevalent Than Acute CINV Delayed emesis is 2.5 times more prevalent than acute emesis For moderately emetogenic chemotherapy – Delayed nausea exceeds acute nausea by 16% – Delayed emesis exceeds acute emesis by 15% For highly emetogenic chemotherapy – Delayed nausea exceeds acute nausea by 27% – Delayed emesis exceeds acute emesis by 38% Grunberg SM, et al. Cancer. 2004;100:2261. Patients with Delayed Nausea/Vomiting (%) 5-HT3 Antagonists Are Ineffective for Controlling Delayed CINV in a Substantial Proportion of Patients 40 Mild nausea Moderate nausea Severe nausea Emesis 38 360 41 34 35 – 322 completed requirements for chemotherapy cycle 1 30 20 25 24 25 25 23 21 17 19 17 15 10 10 5 0 Carboplatin Cisplatin Hickok JT, et al. Cancer. 2003;97:2880. patients at 18 private medical oncology groups were enrolled in the study Doxorubicin Antiemetic regimen – Day 1 30-min prechemotherapy: ondansetron (24 mg PO or 20 mg IV) + dexamethasone (12 mg PO or 10 mg IV) – Remaining days of chemotherapy: regimen that comprised standard care at each practice site % of Patients Who Failed to Achieve Endpoint (Days 1–5) Palonosetron Improves Outcomes, Yet CINV Persists in Most Patients 100 90 80 70 60 50 66 58 49 40 30 20 10 0 No Emetic Episode No Rescue Medication No Nausea* Endpoint *Moderate or severe Brames MJ, et al. Presented at the MASCC/ISOO 18th International Symposium; June 22-24, 2006: Toronto, Canada. Reprinted with permission. Aprepitant Improves Outcomes, Yet CINV Persists in Most Patients 70 % of Patients in Whom CINV Persisted Aprepitant 60 59 56 Standard therapy 50 44* 40 35 39* 30 20* 20 10 0 Acute CINV *P >.001 compared with standard therapy. Poli-Bigelli S, et al. Cancer. 2003;97:3090. Delayed CINV Overall Anticipatory Nausea and Vomiting Anticipatory nausea occurs in 29% of chemotherapy patients1,2 Anticipatory vomiting occurs in 11% of chemotherapy patients1,2 Anticipatory nausea and vomiting – Mostly on the basis of classic or Pavlovian conditioning3 1. Roscoe JA, et al. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20:113. 2. Morrow GR, et al. Support Care Cancer. 1998;6:244. 3. Reesal RT, et al. Can J Psychiatr. 1990;35:80. Cannabinoids for the Treatment of CINV—Distinct Therapeutic Mechanism Combining agents with different mechanisms of action (MOAs) may be the optimal approach to management of CINV1 Cannabinoids have an MOA different from conventional antiemetics (eg, 5-HT3 or D2 receptor antagonists)1-3 The antiemetic effect of cannabinoids may be due to interaction with the cannabinoid receptor system (ie, CB1 receptors found in neural tissues)4 1. National Cancer Institute. Available at: http://www.meds.com/pdq/supportive_pro.html. Accessed June 13, 2007. 2. Tramer MR, et al. BMJ. 2001;323:16. 3. NCCN Practice Guidelines in Oncology. 2005;1. Antiemesis. 4. CesametTM (nabilone). Product Information. San Diego, CA: Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America; 2006. Control of Nausea and Vomiting Cannabinoids—A Systematic Review* 80 Control (placebo or active) Cannabinoid 70 Event Rate (%) 66 60 59 57 57 45 43 40 36 20 0 vs Placebo Nausea vs Active vs Placebo Vomiting vs Active *21 randomized, comparative studies of cannabinoids with placebo or other antiemetics (oral nabilone, oral dronabinol, intramuscular levonatrodol.) Active control = prochlorperazine, metoclopramide, chlorpromazine, haloperidol, domperidone, and alizapride. Tramer MR, et al. BMJ. 2001;323:16. Patients’ Rating Preference for Cannabinoids Preference for cannabinoids vs placebo (4 studies) vs active control (14 studies) 0.5 1.0 2.0 4.0 6.0 8.0 Relative risk (95% CI) Favors cannabinoids 10.0 Active control = prochlorperazine, metoclopramide, chlorpromazine, thiethylperazine, haloperidol, domperidone, and alizapride. Tramèr MR, et al. BMJ. 2001;323:16. Etiology of Pain in Breast Cancer Patients Iatrogenic – Postmastectomy syndrome – Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy Taxanes >> vinorelbine > capecitabine Bone metastases Neuropathic – Malignant plexopathy – Malignant radiculopathy – MSCC Cannabinoids—Cancer Pain European phase III study of a cannabidiol/THC buccal spray1 N = 177 Opioid nonresponsive pain Cannabidiol/THC spray significantly reduced pain compared with placebo (P = .014) 43% of patients showed >30% improvement in pain (P = .024) 1http://www.dpna.org/1sativex.htm Cannabinoids in the Treatment of Other Pain Chronic, incapacitating back pain1 – Multiple Sclerosis (MS) neuropathic pain2 – Decrease in spinal pain intensity and headache with nabilone Cannabinoids (cannabidiol/THC buccal spray, cannabidiol, and dronabinol) were significantly superior to placebo in treating neuropathic pain in MS MS spasticity-related pain3 – Nabilone resulted in a significant decrease in spasticityrelated pain 1. Pinsger M, et al. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2006;118:327. 2. Iskedjian M, et al. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:17. 3. Wissel J, et al. J Neurol. 2006;253:1337. Rx Cannabinoids—Pharmacokinetics Nabilone Dronabinol Oral dosing 1–2 mg 1–3 h before chemotherapy, and BID for up to 48 h afterwards 5 mg/m2 1–3 h before chemotherapy, and every 2–4 h afterwards for a total of 4–6 doses/d Source Synthetic ∆9-THC analog Synthetic ∆9-THC Formulation Crystalline powder capsule Capsule formulated with sesame oil, among other ingredients (contraindicated in patients with a hypersensitivity to sesame oil) Onset of action 60–90 min 30–60 min Peak plasma concentrations (Tmax) 2h 2–4 h Duration of action 8–12 h 4–6 h for psychoactive effects Metabolites 2 active metabolites 2 active metabolites and >20 other metabolites Clearance Major excretory pathway is the biliary system Biliary excretion is major route of elimination Cesamet® (nabilone). Product Information. Costa Mesa, CA: Valeant Pharmaceuticals; 2006. Marinol® (dronabinol). Product Information. Marietta, GA: Unimed Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2006. Cannabinoid Metabolism CYP450 Metabolizing Enzymes CYP450 Enzyme Inhibition CYP450 Enzyme Induction Nabilone 2C9*, 3A4 (aldehyde oxygenase) None to date None to date Dronabinol 2C9*, 2C11, 3A4 (aldehyde oxygenase) 3A4 None to date *Main metabolizing isoenzyme Metabolized principally through the CYP450 2C9 isoenzyme No inhibitory or inducing effect on any of the isoenzymes Competes with very few medications at the metabolic level, including opioids Examples of medications metabolized by CYP3A4: antifungals, methadone, many antidepressants, HIV protease inhibitors Nahas GG, et al, eds. Marihuana and Medicine. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1999: 74-116. Aprepitant Metabolism Oral aprepitant 40 mg 125 mg Inhibitory Effect on Orally Administered CYP3A4 Substrate* Inhibitory Effect on IV Administered CYP3A4 Substrate* Weak Moderate — Weak *Midazolam Majumdar AK, et al. J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;47:744. Side Effects of Cannabinoids* Symptom/Effect CNS Sedation Somnolence Dizziness Euphoria/“high” Blurred vision Anxiety; panic Paranoia Psychosis Depression Ataxia Asthenia Cognitive effects Cardiovascular Postural hypotension Vasodilatation (red eyes) Tachycardia Palpitations Others Dry mouth Headache Most Common 4 4 4 Common 4 4 4 4 4 Rare 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 *If smoked, respiratory effects, such as bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung infection. Clark AJ. Pain Res Manage. 2005;10(suppl A):44A. Summary Emesis is mediated by a variety of neurotransmitters; thus, full control may require the blocking of multiple brain receptor sites Current antiemetic agents provide inadequate relief in a substantial number of cancer patients The mechanism of action of cannabinoids differs from that of conventional antiemetics, making it an appropriate candidate for combination with traditional agents Cannabinoids have proven to be effective antiemetic adjuvants in patients with uncontrolled nausea/vomiting and can provide additional relief in patients with severe pain Cannabinoids have demonstrated long-term efficacy and safety Case Study: Breakthrough CINV with Anthracycline-Based Therapy William J. Gradishar, MD, FACP Director, Breast Medical Oncology Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center Chicago, Illinois Ms. J A 44-year-old female presents with a right breast lump, which on physical examination measures ~ 1 cm A mammogram reveals a suspiciousappearing lesion measuring ~ 1.5 cm in the same area noted on physical exam Infiltrating Ductal Carcinoma ER, PR, and HER2 (-) The patient undergoes lumpectomy and sentinel lymph node biopsy, which confirms the presence of a 1.4 cm infiltrating ductal carcinoma that is ER, PR, and HER2 negative Sentinel Lymph Node Negative for Tumor The sentinel lymph node was negative for tumor The patient is referred to a medical oncologist for consideration of postoperative systemic adjuvant therapy Additional planned breast irradiation Medical Oncologist Assessment The assessment of the medical oncologist is that the patient will benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy, and recommends 4 cycles of doxorubicin 60 mg/m2 and cyclophosphamide 600 mg/m2 (AC) Discussion with Oncologist Risk reduction might be expected with this regimen Expected toxicities – Neutropenia, alopecia, cardiac toxicity, mouth sores, fatigue, and nausea and vomiting Reassurance and Management The medical oncologist assures the patient that these symptoms can be prevented or successfully managed should they develop. AC Regimen and CINV The doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide (AC) regimen is one of the most commonly recommended regimens for adjuvant therapy of breast cancer, either as a “stand alone” treatment or to be used in conjunction with a taxane (concurrently or sequentially) Although medical oncologists believe that AC chemotherapy is generally well tolerated by most women, the AC regimen actually falls into the “moderate risk” category (30%–90%) of chemotherapy regimens as it relates to the risk of emesis AC Regimen and CINV When patients are carefully questioned regarding symptom control after receiving a chemotherapy regimen such as AC along with standard antiemetics, many (up to 70%) will indicate that emesis is controlled on day 1 after chemotherapy Only a fraction of patients with wellcontrolled emesis can decrease to 50% on days 2 and 3 following chemotherapy Hesketh PJ, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4112. Poli-Bigelli S, et al. Cancer. 2003;97:3090. Warr DG. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(suppl): abstr 8007. Delayed Symptoms Some patients experience delayed symptoms (24 hours or more after chemotherapy), and the risk of nausea and vomiting increases during multiple cycles of therapy Patients (%) Perception vs Reality in Patients Receiving Moderately or Highly Emetogenic Chemotherapy 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 MD/RN prediction Patient experience Acute Acute Delayed Delayed Nausea Vomiting Nausea Vomiting 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Moderately Emetogenic Chemotherapy MD/RN prediction Patient experience Acute Acute Delayed Delayed Nausea Vomiting Nausea Vomiting Highly Emetogenic Chemotherapy Schwartzberg L. J Support Oncol. 2006;4(suppl 1):3. Prevention of Emesis in Women on Day 1 After Chemotherapy Results with Standard Therapy in Randomized Trials All patients received dexamethasone and ondansetron Patients (%) 100 80 60 AC 69 66 Cisplatin 40 20 0 Cisplatin group (N = 438): all received cisplatin >70 mg/m2 . Anthracycline/cyclophosphamide group (N = 424): 99% received AC. AC = doxorubicine/cyclophosphamide. Hesketh PJ, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4112. Poli-Bigelli S, et al. Cancer. 2003;97:3090. Warr DG. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(suppl): abstr 8007. Prevention of Emesis in Women on Days 2 and 3 Results with Standard Therapy in Randomized Trials Patients (%) On Days 2 and 3: Cisplatin patients given dexamethasone 8 mg bid AC patients given ondansetron 8 mg bid 100 80 60 AC Cisplatin 49 47 40 20 0 Cisplatin group (N = 438): all received cisplatin >70 mg/m2 . Anthracycline/cyclophosphamide group (N = 424): 99% received AC. AC = doxorubicine/cyclophosphamide. Hesketh PJ, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4112. Poli-Bigelli S, et al. Cancer. 2003;97:3090. Warr DG. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(suppl): abstr 8007. Breakthrough CINV In this 44-year-old woman with breast cancer receiving AC adjuvant therapy, breakthrough nausea/vomiting developed despite antiemetic prophylaxis given according to the NCCN guidelines Options for Breakthrough CINV Additional agents should be from a different drug class than initial therapy Possible options include dopamine antagonists, metoclopramide, butyrophenones, cannabinoids, corticosteroids, or agents such as lorazepam NCCN Practice Guidelines in Oncology – Version 1. 2007. Antiemesis, MS-1. Additional Treatment Options for breakthrough treatment were discussed with the patient Dexamethasone + lorazepam were added to her antiemetic regimen Take-Home Messages Many patients receive adjuvant chemotherapy, particularly those with small node negative breast cancers, for an acknowledged small potential benefit (reduction in risk of recurrence) It is incumbent upon oncologists to deliver adjuvant chemotherapy with as few side effects as possible A substantial portion of patients receiving common regimens such as AC experience CINV despite recommended emetic therapy There are a variety of options available for the treatment of breakthrough CINV, these include dopamine antagonists, metoclopramide, butyrophenones, cannabinoids, corticosteroids, or agents such as lorazepam Case Study: Anticipatory CINV and Opioid-Refractory Pain Judith A. Luce, MD Clinical Professor of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco Director, Oncology Services San Francisco General Hospital San Francisco, California Ms. F Ms. F is a 50-year-old Honduran woman who was diagnosed with stage II breast cancer 3 years ago She had been treated with mastectomy, chest wall radiation therapy, 6 cycles of FEC-75 chemotherapy, and tamoxifen She came to our hospital with an enlarging mass in her sternum and severe pain Ms. F Incisional biopsy was performed because of a lack of information from Honduras—the mass was metastatic triple-negative breast cancer Staging revealed 2 other osseous metastases, right neck nodes, and no visceral disease Radiation therapy to the sternal mass was delivered, ultimately helping to reduce pain Patient was started on short-acting opioids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) orally, but said the NSAID irritated her stomach Ms. F Ms. F returns to clinic having lost 2 kilograms, complaining of insomnia, anorexia, terrible pain, nausea, and fatigue. She is tearful and depressed. She spends most of her time on the sofa or in bed Opioids are increased, long-acting opioid prescribed, and sertralene and prochlorperazine given Chemotherapy with weekly paclitaxel and bevacizumab is begun Ms. F The patient is much worse at her next visit. She has had nearly continuous nausea and vomiting on weekly chemotherapy, still has poorly controlled pain, anorexia, and insomnia. She says she had bad nausea after her original chemotherapy also. She complains about “all the pills” but does say that the radiation has helped her pain a lot. Now another bone hurts She is given increased opioids, lorazepam, granisetron, and the chemotherapy is switched to every 21 days Ms. F Ms. F continues to have chemotherapyinduced nausea and vomiting for about a week after chemotherapy She now notes that taking the short-acting opioid makes her more nauseated, but she doesn’t feel any immediate relief from the long-acting drug. She notes “no help” from sertralene and lorazepam, so she stopped them. She has sleepiness from the prochlorperazine Her tumor has progressed Ms. F She remains weepy, discouraged, and the only medications she takes regularly are the short- and long-acting opioids, but she takes the PRN only about twice a day. She has lost 4 more kilograms Taking chemotherapy “time out,” radiation to new bone pain The Perfect Storm This patient has Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV), with a major contribution from anticipatory NV, since her regimen is of relatively low emetogenic potential Anxiety and depression Anorexia, complicated by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) Nausea from her opioids Severe bone pain, not well relieved Poor compliance due to discouragement The Perfect Storm Anorexia Chemotherapy Opioid analgesics Nausea Fatigue Pain All of this Poor compliance Anxiety, depression Poor quality of life Nausea Issues for This Patient Anticipatory nausea and vomiting Still occurs in about 25% of patients in spite of new antiemetics Prevention is key: lower incidence when initial CINV is well managed Memory? Anxiety? Lorazepam, cannabinoids may reduce incidence Treat before chemotherapy Training measures: visualization, acupressure? Nausea Issues for This Patient CINV with delayed nausea About half of all patients experience moderate to severe delayed nausea and vomiting even in this era of better agents Fewer than half of patients with moderate to severe CINV after cycle 1 get an adjustment of regimen before cycle 21 Association of CINV with fatigue, “down time” is quite strong2 Nausea causes greater QOL impact than vomiting3 1. Dibble SL, et al. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2003;30:E40. 2. Dibble SL, et al. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31:E1. 3. Bloechl-Daum B, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4472. Pain Issues in This Patient Fear of opioids, fear of meaning of pain – Better pain control in patients with lower scores on Pain Barriers scale1 – Suggests strong role for patient education, coaching Compliance with regimen – Cancer patients with an average of 8 hours of pain/day complied better with long-acting around-the-clock meds, only 25% with PRNs2 – Better pain management is 1 outcome of support interventions for stress3 – Active phone coaching resulted in better pain control by about 1/34 1. Gunnarsdottir S, et al. Pain. 2002;99:385. 2. Miaskowski C, et al. J Pain. 2002;3:12. 3. Antoni MH, et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1791. Pain Management Adjuncts Antianxiety drugs, usually benzodiazepines Neuroleptics with neuropathic pain activity Anti-inflammatory agents Antidepressants: many possibilities Cannabinoids Topical agents: lidocaine, capsaicin Physical measures: splints, physical therapy, massage, acupuncture, topical physical agents Psychosocial measures: active coaching regimen, relaxation/meditation, group support Cannabinoids and Pain Management Use goes back to ancient times Preclinical data for multiple types of pain mechanisms Synergy with NSAIDS, acetaminophen, mu opiate receptors Clear clinical efficacy in neuropathic pain, including multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) Modulation of inflammation may also help pain—efficacy in RA, postoperative pain Cancer pain studies are fewer – Mostly older studies, small, but randomized – Best was European Sativex study: 43% of patients achieved ≥30% reduction in pain vs placebo1 – Side effects may be more common with THC vs sativex 1http://www.dpna.org/1sativex.htm Cannabinoids and Pain Management Effects Showed in Preclinical Studies Type of Pain Acute Antinociceptive Hyperalgesia Visceral Significant evidence Significant evidence Significant evidence Anti-inflammatory Chronic Neuropathic Significant evidence Significant evidence Significant evidence Due to upregulation of CB1 receptors _______________ Data from animal studies support a role for CB2 receptors CB2 receptors play important role CB2 receptors play important role Allodynia Comparison with opioids Due to up-regulation of CB1 receptors Comparable in potency and efficacy Greater potency and efficacy in both inflammatory and neuropathic pain Lynch M. Pain Res Manage. 2005;10(suppl A). Cross-Reacting Pharmacotherapy Nausea medications Phenothiazines, butyrophenones: sedation, potentially desirable CNS effects Cannabinoids: anxiolytic; synergy with opioids, anti-inflammatory agents; orexigenic NK1 antagonists, 5HT3 antagonists Benzodiazepines: lorazepam reduces anxiety and anticipatory nausea/vomiting; improves sleep Steroids: orexigenic, anti-inflammatory, mood Options for This Patient Better nausea management Continue prochlorperazine, 5HT3 Addition of cannabinoid Regular schedule of administration Medi-set and home nursing coaching Consider, with new chemotherapy: aprepitant, steroid taper Options for This Patient Better pain management Continue around-the-clock long-acting opioid, increase dose Emphasize regular use of PRN short-acting opioid Add cannabinoid Trial of NSAID plus proton pump inhibitor Home nursing for coaching, physical therapy Referral to acupuncture and massage – Change SSRI to either quetiapine or olanzapine – Continue PRN lorazepam Case Study: Noncompliance as a Result of CINV and Pain Kristen Fessele, RN, MSN, AOCN Associate Director, Human Research Services The Cancer Institute of New Jersey New Brunswick, New Jersey Ms. D Ms. D is 38 years old Mother of a 6-year-old son Originally diagnosed with infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the right breast at age 33 – ER/PR negative – Her2/neu amplified by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) Ms. D Received doxorubicin + cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel (trastuzumab was not given adjuvantly outside clinical trials at that time) Had difficulties with postchemotherapy nausea and vomiting, as well as anticipatory vomiting Developed herpes zoster to the left upper chest (C3 dermatome) in cycle 6; continues to experience poorly controlled postherpetic neuralgia Ms. D Relapsed with a solitary pulmonary metastasis 7 months ago – Receives paclitaxel, cisplatin and trastuzumab with a 75% decrease in size of lesion Has recently “forgotten” several lab appointments, and this week did not appear for her treatment appointment “I can’t take this anymore, and nothing you’ve given me is really helping!” Complaining of: Poorly controlled nausea after chemotherapy despite use of 5-day antiemetic regimen posttreatment including – Dexamethasone – Ondansetron – Prochlorperazine Increasing frequency and intensity of postherpetic neuralgia “I dread chemo all week because I know I’m going to feel even worse afterwards…” Patient’s fear of nausea and vomiting is causing her to become noncompliant with her chemotherapy plan – May jeopardize the stability of her disease response Overall symptom burden is draining her coping reserve “I hate this –if I take all those pills, I’m too sleepy to do anything, and if I don’t, I can’t sleep, and I’m tired anyway…” Ms. D has not acclimated to opiate-induced sedation as most patients do, possibly due to her inconsistent dosing pattern Gabapentin, used specifically for her neuropathic pain (as well as for hot flashes due to chemotherapy-induced premature menopause), also induces unacceptable sedation in this patient Topical lidocaine application provides some, but incomplete, relief of postherpetic neuralgia Pain Management Ms. D has used oxycodone 5 mg with acetaminophen 325 mg, 1–2 tablets once or twice daily to make her postherpetic neuralgia pain “almost bearable” Lidocaine patches offer some relief She has also tried gabapentin at varying (but suboptimal) doses and schedules without good effect, as she finds it too sedating to fully escalate Common Opioid-Induced Adverse Effects Nausea/vomiting – Approximately 25% of patients1 – Usually transient2 Sedation – Between 20% and 60% of patients3 – Usually at initiation of therapy or with dose increases4 Constipation – Most common side effect2 Pruritis – Between 2% and 10% of patients3 1. Cepeda MS, et al. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;74:102. 2. Swegle JM, Logemann C. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:1347. 3. Cherny N, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2542. 4. McNicol E, et al. J Pain. 2003;4:231. Opioid-Induced Adverse Effects Risk Factors Gender – Nausea/vomiting are more likely to occur in women than in men1 Race – Nausea/vomiting are more likely to occur in Caucasian-Americans than in African-Americans1 Age – Age-related reduction in renal function may lead to accumulation of opioids and their metabolites1,2 1. Cepeda MS, et al. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;74:102. 2. Forman WB. Clin Geriatr Med.1996;12:489. Approaches for Managing Opioid-Induced Adverse Effects Dose reduction of opioid Symptomatic management of adverse effect Opioid rotation Switching route of systemic administration Cherny N, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2542. Goals More effective, reliable control of nausea and vomiting More effective control of neuropathic pain Increased compliance with treatment plan to allow continued response to chemotherapy regimen Tumor Board Presentation During discussion of challenging management cases at weekly tumor board, Ms. D was reviewed A colleague, trained in Canada, suggested a trial of a cannabinoid adjuvant to improve the symptom cluster Compelling Preclinical Data—More Evidence Is Needed Several studies describe the potentiating effects of opioids and cannabinoids on pain1-3 Systematic review of human studies in BMJ 2001 by Campbell et al noted – “…suggestions of efficacy in spasticity and neuropathic pain”4 1. Cichewicz DL. Life Sci. 2004;74:1317. 2. Manzanares J, et al. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:287. 3. Reche I, et al. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;318:11. 4. Campbell F. BMJ. 2001;323:13. Clinical Trials Under Way Sativex A biologically derived compound of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannbidiol (CBD), administered as an oromucosal spray, is used in the United Kingdom for neuropathic pain and spasticity associated with multiple sclerosis – FDA approved IND status for Cannabis sativa L. extract in 2006, allowing start of phase III trial in the United States to evaluate effect of this compound on patients with cancer experiencing chronic pain GW Pharmaceuticals, 1/4/06 (Press release) Clinical Trials Under Way Nabilone Phase IV multicenter trial of nabilone in patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy – Average, worst pain; pain at night scores – Other QOL measures Phase IV multicenter trial of nabilone in patients receiving initial chemotherapy – Cycle 1: standard antiemetic regimen – Cycle 2: standard regimen plus nabilone Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct/action/GetStudy. Accessed May 16, 2007. Cannabinoid Indications Nabilone and dronabinol1,2 – Nausea and vomiting that has not responded adequately to conventional antiemetic treatments Dronabinol2 – Appetite loss associated with weight loss in people with AIDS 1. CesametTM (nabilone) Product Information. Costa Mesa, CA: Valeant Pharmaceuticals; 2006. 2. Marinol® (dronabinol) Product Information. Marietta, GA: Unimed Pharmaceuticals; 2006. Recommendations Educate patient on – Product nature – Potential benefits – Side effects – Risk of addiction Develop a treatment plan incorporating these goals – Reduction in pain – Increased functional abilities – Improved sleep quality – Increased quality of life – Reduction in the use of other medications Precautions—Nabilone and Dronabinol Use with caution in – Older patients1,2 – Those with current or previous psychiatric disorders (bipolar disorder, depression, schizophrenia)1,2 – Those with cardiac conditions or at risk for tachycardia or orthostatic hypotension1,2 – Those with a history of seizures2 1. CesametTM (nabilone) Product Information. Costa Mesa, CA: Valeant Pharmaceuticals; 2006. 2. Marinol® (dronabinol) Product Information. Marietta, GA: Unimed Pharmaceuticals; 2006. Most Common Adverse Events Nabilone1 Dronabinol2 – Drowsiness – Euphoria (“high”) – Vertigo – Abdominal pain – Dry mouth – Nausea/vomiting – Euphoria (“feeling high”) – Dizziness – Ataxia – Somnolence – Headache – Paranoid reaction – Concentration difficulties – Abnormal thinking 1. CesametTM (nabilone) Product Information. Costa Mesa, CA: Valeant Pharmaceuticals; 2006. 2. Marinol® (dronabinol) Product Information. Marietta, GA: Unimed Pharmaceuticals; 2006. Patient Update/Summary Nabilone was added to Ms. D’s antiemetic regimen on her most recent cycle. She reports good improvement in her nausea control, and no episodes of vomiting. She is continuing use of a pain diary to track dosing of breakthrough opioids, and reports an overall improvement in symptom burden. Conclusions Additional options for symptom management are beneficial, especially for patients with metastatic disease and multiple sources of distress Cannabinoids may prove to be a helpful adjunct to standard antiemetic regimens and to opioids for pain management – Clinical studies are under way to evaluate if cannabinoids may help to reduce the dose of opioids needed

![[Physician Letterhead] [Select Today`s Date] . [Name of Health](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006995683_1-fc7d457c4956a00b3a5595efa89b67b0-300x300.png)