Neema Carmel KN

advertisement

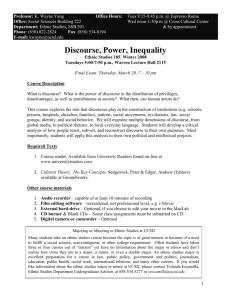

1 AMITHAV GHOSH’S ‘THE HUNGRY TIDE’: A SUBALTERN STUDY A dissertation submitted to Mahatma Gandhi University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts in English Literature. By Neema Carmel K N Reg No: 317088 Supervising Teacher Anu c Vijayan The Post Graduate Department Of English St.Albert’s College Ernakulam June 2013 2 3 Certificate This is to certify that the dissertation titled Amithav Ghosh’s The Hungry Tide : A Subaltern Study by Neema Carmel K N ,Reg .No:317088 is a record of bonafide research carried out by her under my supervision and guidance. Anu c Vijayan Lecturer in Charge St. Albert’s college Ernakulam Dr. A V Vijayan Head of the department of English St.Albert’s College Ernakulam Ernakulam June 2013 4 Declaration I do hereby declare that the dissertation Amitav ghosh’sThe Hungry Tide : A Subaltern study is the record of research work done by me and that it has not previously formed the basis for the award of any Degree, Diploma,Associatefellowship or other similar title or recognition. Neema Carmel K N Reg No:317088 Ernakulam 5 June2013 Acknowledgement First and Formost I would like to thank God the almighty, my creator who showered upon me His Blessings to render this work. I am immensely thankful to my project guide Ms.Anu C Vijayan ,Department of English ,St. Albert’s college, Ernakulam for her advice and guidance provided throughout my endeavour. She had been a great support for me by suggesting certain points and clearing my doubt.I am much obliged to her for concern and overall support. I express my sincere thanks to Prof.A V Vijayan,Head of the department of English, St.Albert’s college, Ernakulam for providing me encouragement and valueable suggestions throughout the work. I wish to acknowledge my sincere gratitude to Prof. Harry cleetus, principal, St.Albert’s College, Ernakulam for providing all facilities to carry out this work. Last but not least I am sincerely thankful to my family who helped me in gathering necessary information regarding my project,all my teachers,my class mate and others who have rendered all possible help on all occasions. Neema Carmel K N 6 Contents Sl.No. Title Page no. 1 Introduction 1 2 Subalternism 5 3 The Hungry Tide 9 4 Subaltern perspective in The Hungry Tide 13 5 Conclusion 26 6 Works cited 29 7 Introduction Amitav Ghosh is undoubtedly one of the most important writers writing in English today. His emergence in the world of India English literature is somewhat recent yet he is one of the few writers respected and admired by different kinds of readers. The lists of finest contemporary Indian English writers remain incomplete without his name. Ghosh’s popularity gained immensely from his second novel ‘The Shadow Lines’. The other bestsellers are ‘The GlassPalace’ ‘The Hungry Tide’and ‘Sea Of Poppies’. Amitav is a noted novelist, an essayist and a non-fiction writer. Amitav Ghosh’s standing in the realms of literature is truly unparalleled. His quintessential style of weaving riveting narratives with a bit of pedagogy is what lends his writings their unmistakable appeal, his love for history is well evident for his writings. Amitav Ghosh was born on 11 July 1956, in Kolkata in a middle class family. His Father was a lieutenant colonel. Hence, he spent much of his childhood travelling around the globe. Amitav received his early education from a school Uttarakhandand later went to complete his graduation from Delhi university. He moved to England for higher studies and in the year 1982,he received his doctoral degree in Social Anthropology from St.EdmundHall, Oxford. Although a PhD in social anthropology, Amitav followed his passion for writing by taking up a job in a print media company . His first job was in a local tabloid called the Indian Express. In 1986, he published his first book The Circle Of Reason. Over the years, Amitav wrote several books such as The Shadow Lines(1988) , In an Antique Land(1992), The Calcutta Chromosome(1995) ,Dancing in Cambodia(1998) , Countdown(1999) , The GlassPalace(2000) 8 The Imam and the Indian(2002), The Hungry Tide(2005), Sea OfPoppies(2008) , and River of Smoke(2011) that won him great adulation. His Books not only earned him the distinction of writer par excellence, but also won Him great laurels for his unconventional themes. His books are loaded with indo-Nostalgic rudiments accompanied with an interesting mix of his personal philosophy and strong post-colonialism themes. ‘Sea of poppies’ won a nomination at the Booker’s prize and got much appreciation from his admirers for his brilliant plot and storyline.Achievements and Awards of Amitav Ghosh has received several awards and recognition for his excellentcontribution in the domain of literature and writing . Some of the awards he haswon are Prix MedicisEtranger , France’s top literary award, for the book of ‘The Circle f Reason’, the SahityaAcademi Award and the AnandaPuraskarfor ‘The Shadow Lines’, Arthur C.Clarke Award for ‘The Calcutta Chromosome’, Frankfurt International e-Book Award for ‘The Glass Palace’ and crossword Book Prize for ‘The Hungry Tide’. Apart from these, he has also received other noted Distinctions like Grinzane Cavour Award in Italy and the Padma Shri by IndianGovernment. His book ‘Sea Of Poppies’ received the Crossword Book Award in2009 and was shortlisted for the man Booker Prize. Because of his distinguished contributions towards literature and his expertise towards teaching , Amitav was granted fellowship in Royal Society of Literature and at the center for studies in social sciences, Calcutta . He also received Dan David Prize for his innovativeInterdisciplinary research across traditional bounds and prototypes.The narrative style of Amitav Ghosh is typically postmodern. Indian writing in English has stamped its greatness by mixing up tradition and modernity in the production of art. At the outset, the oral transmission of Indian literary works gained ground gradually. It created an indelible mark in the mind and heart of the lovers of art . The interest in literature lit the burning thirst of the writers which turned their energy and technique to innovate new form and 9 style ofwriting.Amitav Ghosh is one among the postmodernists. He is immensely influenced bythe political and cultural milieu of post independent India . Being a socialanthropologist and having the opportunity of visiting alien lands, he comments on the present scenario the world is passing through in his novels. Cultural fragmentation, colonial and neo-colonial power structures , cultural degeneration,the materialistic offshoots of modern civilization ,dying of human relationships , blending of facts and fantasy , search for love and security ,diasporas, etc … arethe major preoccupations in the writings of Amitav Ghosh.The elemental traits of postmodernism are obviously present in the novels of Amitav Ghosh. As per post modernist, national boundaries are hindrance to human communication. They believe that Nationalism causes wars. So post-modernists speak in favour of globalization. Amitav Ghosh’s novels center around Multiracial and multiethnic issues; as a wandering cosmopolitan h roves around and weaves them with his narrative beauty. In ‘The Shadow Lines’ Amitav Ghosh makes the west and east meet on pedestal of friendship , especially through thecharacters like Tridib,May,Nice Prince etc. He stresses more on the globalizationrather than nationalization. In ‘The Glass Palace’, the story of half –bred Raj Kumar revolves around Burma, Myanmar and India. He travels round many places freely and gains profit. Unexpectedly, his happiness ends when his son is killed by Japanese bomb blast. The reason for this calamity is fighting for national boundaries. Amitav Ghosh has been credited for successfully mastering the genre known as ‘Magical realism ’which was largely developed in India by Salman Rushdie and inSouth America by Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Ghosh is “belonging to thisinternational school of writing which successfully deals with the post-colonial ethos of the modern world without sacrificing the ancient histories of separate lands”.(Anita Desai,1986:149; The criterion :An international 10 Journal in English).Like Salman Rushdie, Amitav Ghosh perfectly blends fact and fiction with magical realism. He reconceptualizes society and history. He is so scientific in thecollection of material, semiotical in the organisation of material, so creative in theformation of fictionalized history.Amitav Ghosh weaves his magical realistic plot with postmodern themes. Self-reflexity and confessionality characterize fictional works of Amitav Ghosh. Dispalcement has been a central process in his fictional writings; departure and arrivals have a permanent symbolic relevance in his narrative structure. Post modernism gives voice to insecurities, disorientation and fragmentation. Most of his novels deals with insecurities in the existence of humanity , which is one of the Postmoderntraits.Postmodernism rejects western values and beliefs as only a small part of the human Experience and rejects such ideas,beliefs, culture and norms of the western. In The Hungry Tide, Ghosh routes the debate on eco-environment and cultural issues through the intrusion o the west into east. ‘The Circle of Reason’ is an allegory about the destruction of traditional village life by the modernizing influx of western culture and the subsequent displacement of non-European peoples by imperialism. In An Antique Land, contemporary political tensions and communal rifts were portrayed. Postcolonial migration is yet another trait of postmodernism. In The Hungry Tide,the theme of immigration , sometimes voluntary and sometimes forced ,along with its bitter/sweet experiences, runs through most incidents in the core of the novel. Irony plays a vital role in the postmodern fiction . The writers treat the subjects like World War 11,communal riot, etc, from a distant position and choose to depict their histories ironically and humorously. Postmodernists defend the causeof feminists. Blurring of genres, one of the postmodern traits ,can be witnessed in the writings of Amitav Ghosh. He disfigures by blending many genres. GirishKarnard rightly 11 said about him , “Ghosh uses to great effect a matrix of multiple points of view in which memory , mythology and history freely interpenetrate……A delight to read”(Indian Express) Chapter– 2 Subalternism Subaltern, meaning ‘of inferior rank’, is a term adopted by Antonio Gramsci to those groups in society who are subject to the hegemony of the ruling classes. Subaltern classes may include peasants, workers and other groups denied accessto ‘hegemonic’ power. Since the history of the ruling class is realized in the state, history being the history of states and dominant groups, Gramsci wasinterested in the historiography of the subaltern classes. In ‘Notes on Italianhistory’ he outlined a six point plan for studying the history of the subalternclasses which included:(1)Their objective formation;(2) their active or passive affiliation to theDominant political formations;(3) the birth of new parties and dominated groups (4)theformation that the subaltern groups produce to press their claims(5) new formations within the old framework that assert the autonomy of the subaltern classes and other point referring to trade unions and political parties.(Gramsci 1971: 52;the key concepts of post colonialism) . In post - colonial theory ,the term Subaltern describes the lower classes and the margins of the society – a subaltern is a person render without human agency , by his or her social status. The term has adapted to post – colonial studies from the work of the subalternStudies group of historians, who aimed to promote a systematic discussion of Subaltern themes in South Asian Studies. It is used in Subaltern Studies ‘as a name of general attribute of subordination in South Asiansociety whether this is expressed in terms of class, caste,age,gender and office or in any 12 other way’. Thenotion of the subaltern became an issue in post – colonialtheory when Gayathrispivak critiqued the assumptions of the assumptions of the Subaltern Studies group in the essay ‘Can Subaltern Speak?’This question sheclaims is one that the group must ask. Her first criticism is directed at the Gramscian claim for the autonomy of the subaltern group which she says noamount of qualification byGuha – who concedes the diversity , heterogeneity andoverlapping nature ofsubaltern can save from its fundamentally essentialist premise. The people or thesubaltern is a group defined by its difference from the elite.To guard against essential views of subalterneityGuha suggests that there isa further distinction to be made between the subaltern and dominant indigenousgroups at the regional and local levels. Spivak goes on to elaborate the problems of the category of the subaltern bylooking at the situation of gendered subjects and of Indian women in particular , for ‘both as an object of colonialist historiography and a subject of insurgency, the ideology construction of gender keeps the male dominant ’.‘Can Subaltern speak?’ by GayathriSpivak relates to the manner in which western cultures investigate other cultures. Spivak uses the example of Indian Sati practices of widow suicide, however the main significance in that is ,in the first part which presents the ethical problems of investigating a different culture base on “universal” concepts and frame works. Spivak examines the position of Indian women through an analysis of a particular case ,and concludes with the declaration that ‘the subaltern cannot speak’. This has sometimes been interpretedto mean that there is no way in which oppressed or politically marginalized groupscan voice their resistance , or that the subaltern only has a dominant language or a dominant voice in which to be heard . But Spivak’s target is the concept of an unproblematically constituted subaltern identity, rather than the subaltern subject’s ability to give voice to political concerns. Her point is that no act of dissent or resistance occurs on behalf of an essential subaltern subject 13 entirely separate from the dominant discourse that provides the language and the conceptual categories with which the subaltern voice speaks. Clearly, the existence of post – colonialdiscourse itself is an example of such speaking and in most cases the dominant language or mode of representation is appropriated so that the marginal voice can be heard. In the 1970’s, the application of subaltern began to denote the colonized peoples ofThe south Asian subcontinent, and described a new perspective of the history of anImperial colony, told from the point of view of the colonized man and woman,rather than from the points of view of colonizers; in which respect, Marxist historians already had been investigating colonial history told from the perspectiveof the proletariat. In the 1980s,the scope of subaltern studies was applied as an“intervention in south Asian historiography”.As a method of intellectual discourse , the concept of the subaltern occasionallyProved culturally problematic, because it remained a Eurocentric method of historical enquiry when studying the non – western peoples of Africa ,Asia, andthe Middle East. From having originated as an historical – research model for studying the colonial experience of South Asian peoples, the applicabilityof the techniques of subaltern studies transformed a model of intellectual discourse into a method of vigorous post – colonial critique. The intellectual efficacy of the subaltern eased its adaptation and adoption to the methods of investigation in the fields of history, anthropology, sociology, human geography, and literature. In Marxist theory, the civil sense of the term subaltern was first used by the Italiancommunist intellectual Antonio Gramsci(1891- 1937), possibly as a synonym forthe proletariat. In several essays, the post – colonial critic Homi K. Bhabha, emphasized the importance of social power relations in defining subaltern social groups as oppressed, racial minorities whose social presence was crucial to self definition of the majority groups as such 14 subaltern social groups nonetheless, also are in a position to subvert the authority of the social groups who hold hegemonic power. The subaltern are the peoples who have been silenced in the administration of the colonial states they constitute, they can be heard by means of their political actionseffected in protest against the discourse of mainstream development, and, thereby, create their own, proper forms of modernization and development .Hence do subaltern social groups create social, political, and cultural movementsThat contest and disassemble the exclusive claims to power of the western imperialist powers, and so establish the use and application of local knowledge to create new spaces of opposition and alternative, non – imperialist futures. 15 Chapter – 3 The Hungry Tide In 2004, Ghosh published his latest novel, The Hungry Tide. It stands in Immediate contrast to the grandeur of The Glass Palace. Although it employsmany of the narrative techniques of the earlier novels, such as the ‘double – helix’pattern of alternate narrative strands, the use of flashback and memory , and the insertion of textual fragments that offer alternative avenues into a forgottenhistory, its scope is less ambitious than most of Ghosh’s previous works. For themost part, the narrative time frame only extends over some thirty to forty years and, in contrast to the Diaspora peregrination of his earlier novels, the action is concentrated in one geographical area. Set amongst the small, impoverished and isolated communities of the sundarbans, the mangrove swamps that congregate atthe mouth of the huge Ganges Delta, it returns to the themes of modernity and development which he had introduced into his writing with In an Antique Land.This is braided, moreover, with that strand in Ghosh’s work which has concerned Itself with the issues of scientific knowledge and its relationship to subaltern waysof thinking and being. A principle figure in The Hungry Tide is a scientist, this time a cytologist called Piya Roy. Cytology involves the study of marine mammals, and their particular Field of expertise concerns the freshwater river dolphins that are to be found inAsia’s great waterways the Indus, the Mekong, the Irawaddy, and, of course, the Ganges. The daughter of an Indian emigrant to the United States, she has had little Contact with her ancestral country but she is drawn to her 16 parents’ native Bengal inorder to conduct a survey of the marine mammals in the Gangatic delta. The novelopens with her meeting with one of the other principal characters, an urbane ,highly educated representative of modern India called Kanai. Significantly , he is a translator by profession , expert in six languages and proficient in several others,but he is also the nephew of an elderly women , called Mashima by the localpeople, who has established an extremely successful rural development organisation called the badabon Trust: an exemplary non – governmental development agency that has built up a rudimentary modern infrastructure including a school, a hospital and other welfare provisions. Kanai, however, is on his way to the Sundarbans to examine a newly recovered Notebook written by his deceased uncle, a poet and scholar whose dreams of socialist revolution are first dashed and then revived by his experience of ‘the tide country’ as he calls it. The notebook he has left behind allows him to reprise the theme of a coercive post – colonial governmental machinery first broached in The Circle of Reason.Piya Roy, the American cytologist is drawn into a curious love triangle involving the local fisherman Fokir , who helps her to locate dolphins in remote Garjontolapool; and KanaiDutt, a Delhi Dilettante, who is visiting his Aunt , Nilima. Yearsearlier, Nilima’s husband, the Marxist teacher Nirmal, had become involved inaiding and assisting a displaced refugee population who had settled on the sundarbans island of Morichjhapi. Among these refugees was Kusum, mother ofa then infant Fokir. In another love triangle of sorts, Nirmal had been motivatedto help the refugees out of love for Kusum, who was also being assisted by Horen. In the present, kanai has returned to the tide country from Delhi to read a‘lost journal’ written by his dead uncle, Nirmal. This recounts the final hoursBefore Morichjihapi island was forcibly cleared of refugees by police a Military troops following a protracted siege. Kusum was killed – in a cyclone,While guiding Piya on one of the tide 17 country’s many remote water ways. In anOdd resolution, Piya decides to continue her aquatic research in the tide country, And asks Nilima to help her set up a research trust , as a memorial to Fokir. She also asks Kanai to be her partner in thisventure.TheHungry Tide is a book about reading abook. Nirmal’s secret journal is discoveredand read by kanai as part of a larger sequence ofevents during his relationship with Piya andFokir. To kanai, the act of reading takes place while on a river boat with Piya and Fokir,waiting for the discovery of the Gangatic dolphin, feeling a measure of jealousy over Fokir’srelationship with Piya. The morichjhapi massacre, which took place in 1979, dramatizes the conflict between different ways of thinking and being, between the logic of modernity anddevelopment and ensuing politics of ecology on the one hand, and the ways of life of indigenous peoples and their relationship to the environment .These conflicts are explored and echoed in the relationships between the main three characters: the scientist, Piya; the modern Indian, Kanai; and an illiterate son of the tide country, a fisherman called Fokir. It is the tide country the novel’s central metaphor that constitutes the common point of referencethat binds Piya, kanai, and fokir together. As the novel makes the clear, the tide is a scientificphenomenon needs to be comprehend by people like Piya, is integral to the rhythms of life for people like Fokir, and it is also a text that is read differently by such people. Kanai is the bridge,the one who is able to translate the idioms of one into that of the other. As the novel reaches its climax, it is finally the environment itself, in the form of an unforgiving storm, whichcomprises the most significant character in the narrative.. The ‘tide country’ is the central metaphor that constitutes the common point of reference that binds Piya, Kanai and Fokir together. As the novel makes clear the tide is a scientific phenomenon that needs to be comprehended by people like Piya, is integral to the rhythms of life 18 for people like Fokir. Kanai is the bridge, the one who is able to translate the idioms of oneinto that of the other.The Hungry Tide is a novel which foregrounds language and textuality, and its relationship to lived experience. As the three of them launch into the elaborate backwaters, they are drawn unawares into the hidden undercurrents of this isolated world, where political turmoil exacts a personal toll that is every bit as powerful as the ravaging tide. Already an international success, The Hungry Tide is a prophetic novel of remarkable insight, beauty, and humanity.TheNarrative is meandering, long, slow, often covering over the previous happenings until the right time, much like the topography it is set in. Not particularly predictable, it still is gradual enough to allow reader to be patient and trust the author to reveal the clever undercurrents running through the story eventually. The Writing utilizes various devices, including portraying the pragmatism and superstition, merged together in an erratic but effective mix of lifestyle of the villagers of the Tide Country. My favorite aspect of the book was the very writing, which was a cerebral pace much akin to the very boats that traverse the rivers and delta of the Tide country, lolling and rolling, pacing up and down depending on the currents of the story itself, much dependent, like a boat is on the river it is crossing. 19 Chapter – 4 Subaltern Perspectives in The Hungry Tide Society is a place where a person or groups strive to attain equilibrium in cultural, social, political, economical aspects with a person or groups who possess the power to utilize it. Some people still lack behind in becoming the creative part of the society. It may include immigrants, migrants, expatriate, refugees, marginal and subalterns. Etymologically the word subaltern means ‘of inferior rank’. It used to demonstrate the person or groups, who are lower in position or rank. “Subaltern” is a British word for someone of inferior rank, and combines the Latin terms for ‘under’ (sub) and ‘other’ (alter). It includes workers, homeless, peasants, women etc. According to the post – colonial critic, Homi Bhabha, subaltern is a minority group who yearns for the hegemonic power and endeavor to access it. RanajitGuha established Subaltern Studies group. It intends to study to historiography of subalterns and subaltern themes in South Asian Studies. The group published ‘Selected Subaltern Studies’ (1988) , which examines the social, political, economical and historical status of subalterns in the elite society. In this reference Leela Gandhi has remarked as: “In other words, subaltern studies defined itself as an attempt to allow the people finally to speak within the jealous pages of elitist historiography and in so doing, to speak for, or to sound the muted voices of the truly oppressed ” (The Criterion: An International Journal in English;vol.3,issue:3). 20 Gayathrispivak’s essay ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’ popularized the term subaltern in the post – colonial theory. Spivak’s analytical study of the subaltern is gender oriented. She has particularly focused on the females of the third world as the subaltern. Spivak opines that the patriarchal society and colonial power have doubly oppressed the female of the third world. According to all these studies there are some tenants for this theory, they are 1. Subaltern are voiceless, they are unheard 2. Subalterns have no history. Need to reappraise the historiography of elite class. 3. Exclusion of subaltern from accessing the hegemonic power. 4. To resist the domination of upper class. Amitav Ghosh is the most contemporary novelist whose novels deals with the most contemporary issues such as modern man’s perennial problems of existential crisis, problems of alienation, problems of restless, rootless and unsettled, problems of marginalization. Ghosh’s The Hungry Tide narrates the misareble life of Bangladeshi refugees and the Morichjhapi massacre. He had depicted the unfulfilled hopes and aspiration of the post war and post partition subaltern classes of the sub continent. The problems which are depicted in the novel are the post war aesthetics of postcolonial migration and settlement of refugees and orphan.The novel is an account of the journey of an Indo – American cytologist Piya Roy. Fokir, a fisherman who assisted Piya in her research for the river dolphin. Kanai, a Delhi based business man set out to Lusibari on the request of his aunt Nilima, who invited him to read the journal of his dead uncle, Nirmal. In the novel Nirmal and Horen are the witnesses of the Morichjhapi massacre of Bangladeshi refugees. The refugees come from Bangladesh after the partition. Kusumwith her little child, 21 Fokir, returns along with refugees in sundarbans. Kusum resist forthe rights of refugees and is killed in assault. Nilima narrates the incident of Morichjhapi carnage to kanai she says: “…In Bangladesh they had been among the poorest of rural people, oppressed and exploited both by Muslim communalists and by Hindus of the upper castes.”(HT 124). The novel brings forth the history of post – partition India and the crisis occurred. The refugees come from east Bengal and are sent to Dandakaranya, Madhya Pradesh in 1961. They are forced to settle and live there in an unhealthy atmosphere and have to face the assailant by native tribes. Thus they are harassed and remain unheard. In the novel, Nirmal’s diary entries recounting Morichjhapi and the plight of the Fokir’s mother Kusum serve as a true reality of the sundarbans. On the Morichjhapi island, the refugees construct their small world of happiness. Kusum invites Horen and Nirmal to participate in their celebration of getting home. Nirmal says:Was it possible, even that in Morichjhapi had been planted the seeds of what might become if not a Dalit nation, then at least a safe heaven, a place of true freedom for the country’s most oppressed (205). The dreams of these refugees very soon come to end, when they are asked to turn back to their previous place. Kusum expresses her violent anger by questioning, which makes Nirmal totally dumb and helpless. Bengal government declares Morichjhapi island as the area of preservation for animals. Kusum asks, “who are these people…who love animals so much that they are willing to kill us for them?”. The refugees fought for survival, became the victim of Morichjhapi after the water and food supplies were cut off to the islands to coerce the refugees to flee. The police forces arrive in Morichjhapi forpatrolling and announcing consistently to abandon the 22 place. They not only destroy tube wells but also impede the supply of ration which results in starvation. “Who are we? We here do we belong? … We are the dispossessed. ” The above cited quotation of rootlessness expresses the hollow life of the refugees, who wander aimlessly in search of their existence and sits there helpless and listening to then policemen making their announcements, hearing them say that their lives, their existence was worth less than dirt and dust.(284). Homi Bhabha, the most important thinker of post colonial thought, propounded that the importance of power relations in the subaltern groups as had been focused as oppressed minority groups whose presence was crucial to the self definition of the majority group: subaltern group of the social structure also in a position to subvert the authority of those who had hegemonic power. The refugees of the novel who are the victims of the constructed East Bengali Muslims as the ontological ‘other’ who are every – where depressed, oppressed and as well as marginalized. The eminent critic of subaltern is GayathriChakravortySpivak whose epoch – making line is fully apt – “Can the subaltern speak?” implies that silence is the critical component of subaltern identity. Interestingly the maneuvering the Dalit and the gendered subaltern Kusum’s story retold by the male and elite class representative Nirmal.The role and the complexities of the subaltern language also very prominent in the text of the novel. The ethnicity and the gender intersections are the crucible for articulating the relationship between internal colonialism and subaltern studies which has been prominent in novel – The hungry Tide. The refugees, explicitly, are people without financial, commercial, or political power. As the refugees reached India they understood that they were not entirely welcome here either. The refugees were the subaltern classes who were forced to seek out a dwelling elsewhere but 23 unfortunately forced to shelter into resettlement camp some where in central India.‘They called it resettlement ’, said Nilima, ‘but people say it was more like a concentration camp, or prison. They were surrounded by security forces and forbidden to leave. Those who tried to get away were hunted down. (HT124). This narrative part shows the political brutality towards the refugees. And here they can’t speak against these and it again proves the silence of the subalterns. Nirmal, a revolutionary during his earlier days is enthused by the spectacle of resilience shown by the Morichjhapi incidents. He decided to record everything in his book so that history can get certain publicity through the kanai. Nirmal in his journal finds a strong utopian strand in his endeavor, in his attempt by the dispossessed to possess something of their own. It is brutally repressed by the government forces and aftermath Kusum is killed. Nirmal as a Marxist believed in rapprochement across class barriers that can bring subaltern people and the elite together which generation later Piya repeats with Kusum’s son Fokir. The inherent cause of the brutal violence, the Morichjhapi was for a long time in both for ban academia and popular imaginary can be attributed to the invisibility of the low caste and class identity. The west Bengal state committee meeting in 1982 also justified the eviction by pointing out that the refugees could not given any shelter under any circumstances. Ghosh is questioning this decision of government and to the global people through Kusum, “who are those people, I wonder who love animals so much that they are willing to kill us for them.”(HT 284). Through these words of Kusum Ghosh is trying to show the brutality of elite class people towards a subaltern group, a group of refugees. So the condition of the dispossessed, displaced, 24 dispriviledged is unpredictable and hostile in the terrain of the sundarbans. The massacre, the tiger killing Kusum’s father and Fokir’s vulnerability to the state officials are instance in the novel that depicted the subaltern as well as the marginalized people’s predicament. The voice of the common men, their struggle and sacrifices which went unnoticed in the annals of the history began to get a prominent voice in the fiction of Amitav Ghosh in a different way. History ceases to be the forte of those who wield power. In the recent period novelists are currently obsessed with in acquiring the lost history in which the powerless, marginalized and subjugated expresses themselves and move towards the center. But the centre and the dream of oppressed of finding a voice meet a silent death. Amitav Ghosh portrays these subaltern classes with using history as a tool which at least come to terms with our troubling present. The HungryTide as a whole constantly reflects subaltern relationships; the elite western and eastern characters respond to the impoverished Indian characters and in turn the reader and the characters respond to the animals in the novel – namely the tigers – and adding one more thread to this relational web, both the rural poor and the tigers all have to potential to turn against their elite oppressors. All these relationships and connections are multifaceted and are in constant transitions of balance of power and understanding. In terms of the subaltern being faced with the cosmopolitan and being subject to metropolitan dominance. The relationship between kanai and Fokir, is a model in which the relation displays the imposing the rule over the marginalized. We may say this kind of relation as a relation between city over rural. This kind of dominance is displayed in The Hungry Tide by the authorities’ treatment of the people of the tide country. 25 Spivak confronts the issue of allowing subaltern voices to manifest against the might of colonial and elite powers. In the case of The Hungry Tide the subaltern are the rural poor of west Bengal. When these impoverished eastern people exist in a world dominated by the west, the issue must be confronted with regards to their ability to have their voices heard and their opinions matter, as Spivak comments: “We must now confront the following question: On the other side of the international division of labor from socialized capital, inside and outside the circuit of the epistemic violence of imperialist law and education supplementing an earlier economic text, can the subaltern speak?(Spivak 283) Spivak’s concern is with the politically and socially silenced subaltern, it is an injustice which requires a resolution. She suggests that some resolve exists in the narrative that elite Indians can provide on behalf of the subaltern Indians, yet this is still not sufficient: “Certain varieties of the Indian elite are at best native informants for first world intellectuals interested in the voice of the other. But one must nevertheless insist that the colonized subaltern subject is irretrievably heterogeneous” (Spivak 284). Kanai is Ghosh’s example of the Indian elite and to some extent he does speak for Fokir and may be included as a heterogeneous subaltern voice as he is not a westerner like Piya. Kanai’s representation of Fokir however is somewhat clouded by his pride in caste and his need for superiority. Ghosh joins Spivak in her struggle to give the subaltern a voice and to empower this group of people. Spivak is opening a window to an alternate history by drawing forth the subaltern voices from among the ruins of the British Empire to counteract the dominating colonial narratives. In a 26 post colonial world, colonial rule has fallen and with it, its biased historical narratives must be challenged also. Spivak is initiating an empire writes back movement in her statements and it is writings like these which echo in Ghosh’s character of Fokir, the subaltern Indian man. Kanai is often found to speak or translate for Fokir when he speaks to Piya; therefore he both speaks for the uneducated subaltern and displays the dominance of his caste through verbal language. Here Ghosh had engaged with the class division theory of Spivak. In The Hungry Tide, the challenge of the dispossessed is registered via the human make up of the tide country. Each invader to the country was compelled by the government to leave the place and seek for new start. The island of Lusibari had first been populated as result of a philanthropic colonialist, the Scot Sir Daniel Hamilton, who had bought land from the forestry department in order to give an impoverished rural population a chance to settle new land and begin new agricultural projects. We can consider this story as an example for colonisationand the western invasion to east The novel’s four major women characters can be widely categorized based on their cultural positioning as rural and urban women. Nilima and Piya, the urban group of women are in a sense alien to the Sunderban topography in that they were not born into these adverse surroundings and had not been culturally conditioned into its rules of survival. Culturally removed by their superior learning and upbringing both these women are at pains to accustom themselves with the harsh realities of the rural life. Removed from their cloistered urban lives Nilima and Piya develop their personal networks - each unique in their application to forge a deal with their combative surroundings. The zeal and determination that these women exhibit even at face of terrible personal crisis have been faithfully chronicled in the text. 27 Married to Nirmal, the staunch Marxist, Nilima had long lost her husband to his revolutionary zeal and poetic temperament. Displaced from the comforts her affluent middle class upbringing Nilima seeks to construct some permanence within the unsettling flux she suddenly encounters. Out of the ashes of her lost faith in her husband’s impractical Marxism she creates her phoenixthe island’s MohilaSongothon – the Women Union – and ultimately the Badabon Trust. Years of hard work and dedication turns it into a beacon of hope amidst the general gloom of the water ravaged countryside. While Nirmal mellows in his poetry and idealism Nilima’s backbreaking efforts bear fruit, and Lusibari hospital becomes a model medical facility to the deltaic population. Nirmal’s hunger for a revolutionary moment in his life drives him to Morichjhâpi but Nilima is worldly wise and knows that their efforts can only end in self annihilation. Although sympathetic to the plight of the Morichjhâpi refugees her prosaic nature intervenes for the greater good. She stubbornly isolates herself and her organization from the revolutionary zeal that had gripped the islanders even at the cost of losing her husband to her rival and his muse, Kusum. To Nilima “the challenge of making a few little things better in one small place is enough" while for Nirmal "it had to be all or nothing". (387) However Nilima’s voice is muffled under the mad crescendo of Nirmal’s poetic hallucinations. The agency of language remains loyal to the patriarchy so that Nirmal’s ‘notebook’ – a metaphoric male discourse gains in supremacy under its new patriarchal benefactor, Kanai. Thus towards the end of the novel we hear the ‘subaltern’ Nilima’s pain stricken plea:‘And after you’ve put together his notebook, Kanai,’she said quietly, ‘will you put my side of it together too?’Kanai could not fathom her meaning. ‘I don’t understand?’‘Kanai, the dreamers have everyone to speak for them,’ she said. ‘But those who’re patient, those who try to be strong, who try to build things - no one ever sees any poetry in that, do they?’ (HT 387) Kanai however sees ample poetry in Piya, the migrant cytologist who soon 28 turns to be the object of his male ‘gaze’. In spite of her superior learning and global upbringing she can’t help but fall a prey to corrupt and vulgar forest officials. Stripped of the luxury of the vernacular, Piya is truly a ‘subaltern’ until Fokir rows her to the safe haven of the dolphin’s pool. It is among these river dolphins that Piya regains her natural strength and confidence. A troubled childhood and a nasty affair have permanently silenced her so that she prefers the humbling presence of nature to human conglomerations. Her passionate involvement with the Irrawaddy Dolphin can only match Nilima’s obsession with the Trust hospital. Piya’s mobility and rootlessness creates a false sense of empowerment which runs her into the perils of negotiating multiple spaces for herself. Piya is left vulnerable to the ploys of patriarchy bereft of any emotional or social stilts against the harsh realities of a migrant life. Cocooning herself in the gravity of her scientific work this globe totter had tried to save herself from future damage only to be exposed in a primitive encounter with the man of the ‘other’ world, Fokir. Fokir breaks through her shell so that she is able to communicate with him at supraverbal level. But Nature intervenes and Fokir dies trying to save her. Fokir’s death dooms Piya to a life of perpetual guilt. A rajavritta ‘widow’, Piya is condemned to a life of silence, unable to overcome the death of the man who had changed her life. But the grim realities of Sunderban and the resultant flux fortify Piya beyond any simplistic binaries so that she can exploit her mobility to build public opinion over the sensitive ecology of this Gangetic delta. The rural women of this marshy habitat have developed their own set of survival tactics unique and different from privileged order of urban women in that they draw sustenance from primitive belief structures and social norms. Positioned in an altogether different societal infrastructure than Piya and Nilima these native women of deltaic Bengal, Moyna and Kusum have sharpened their own tools of survival. However a similar upbringing cannot gloss over the 29 generational gap in the multiple aspirations of these women. The Sunderban women of a lost generation of Kusums had craved for a portion of land to claim as their own while the Moynas of the present anchor themselves on modern education and learning to get on in life and break free of their oppressive surroundings. Thus the ever silting topography of the region echoes in the changing aspirations of the women and the novel methods they adopt to counter Nature’s brute forces. It is an obstinacy to survive that makes Moyna the most haunting character in the novel. Oppressed and deprived under the patriarchal control Moyna braves all odds to educate herself and get on in life. But no sooner had she taken flight than she is perpetually shackled by the chains of patriarchy in an unequal marriage to the illiterate Fokir. Never abandoning her dreams to qualify as a nurse Moyna coaxes her husband to move to Lusibari and give proper education to her son. Her marital tussle with her unpragmatic husband echoes similar battles between Nilima and Nirmal. To complicate matters Moyna is a mother so her son’safety weighs utmost in her mind: ….It’s people like us who’re going to suffer and it’s up to us to think ahead. That’s why I have to make sure Tutul gets an education. Otherwise, what’s his future going to be? (HT 134)Fokir, her fisherman husband however loves to take his only son to his numerous fishing expeditions thereby endangering both their lives. Moyna, the rooted subaltern stands in sharp contrast to Piya, the globe totter. What Piya has lost in her multiple voyages; Moyna has gained in her rootedness. Piya, the migrant finds it difficult to negotiate her space in the modern western society where she is at pains to fit, or in the Sunderbans a part of her long forgotten past where people cheer the immolation of a tiger. Bereft of the traditional support structures of marriage and family Piya is constantly victimised as she inadeptly tries to fit the diverse roles bestowed by an alien world. The apparently disadvantaged Moyna on the other hand has developed her 30 personal networks through her association with the Trust hospital – a precious weapon to survive the contingencies of Sunderban life. Even when nature takes its final toll on her, the widowed Moyna, like Mahasweta Devi’s ‘the five women’in After Kurukshetra: Three Stories is better able to bear Fokir’s death. Born into the complexities of refugee life in the SunderbansFokir’s mother Kusum had instinctually learnt its lessons of survival. The myth of Bon Bibi had long served as a source of sustenance, an anchor of belief for the people of ‘the land of eighteen tides’. Women had chanted the name of Bon Bibi, the saviour of the land for the safe passage of their kin. Kusum had lost her father to the snares of the dreaded tiger, animating out of the legend of DokkinRai, the demonic oppressor. She had however never lost faith in Bon Bibi and her mercy – a belief structure moulding her survival strategies. Even when her family tears apart after the untimely death of her father, Kusum never runs out of spirit. Vulnerable to vulgar mercenaries she finds herself uprooted from the soft yielding mud of her native land to the sooty town of Dhanbad. Kusum strikes the best possible deal with life and marries Rajan banking on the traditional support structure of marriage to keep trouble at bay. However the subsequent death of the husband and the onrush of the uprooted refugees back to the tide country sweep her to the familiar yet hostile countryside. Unlike Nirmal or Horen, Kusum aims to build something concrete through her active involvement in the Morichjhapi project. As things turn sour and the Morichjhapi refugees, trying to resettle on conserved land are brutally exterminated by government forces, Kusum becomes one of their many preys. Kusum’s life lived in a flux and her brutal end reverberate the vulnerable niche the subaltern has constantly to negotiate in their adverse surroundings. However Kusum ensures the safety of her son Fokir, the best possible bridge under these situational 31 contingences to span the binaries of rural/urban, inter-religious and cross cultural divide. And the string that binds all these ‘widowed’ women together, the hospital or rather the Badabon Trust, has turned into a source of substance and weapon to fight the claws of widowhood in the ‘tide country’. Nilima’sMohilaSongothon becomes a source of female bonding that helps these women both urban and rural to find a reason however small to live. To Nilima it becomes an oblique escape from the frustrating emptiness of marriage, to Kusum a haven though temporary from the cruelties of an orphan life, to Moyna her only chance to get on in life and finally to Piya a sponsorship and hence a reason to stay connected with Fokir’s tide country. The female networks that these women develop help empower them and many such subaltern women of the region. The heroics of these unknown women of Sunderbans had long eluded the realms of history. Ghosh’s The Hungry Tide chronicles the daily negotiations and bargains of these subaltern women with the ‘jowar’ and ‘bhata’ of their lives and thus rescues them from being obliterated to anonymity by the ‘flood of history’. Through these four characters Ghosh is trying to engage his novel with that of Spivak’s theories on women as subalterns. 32 Conclusion Ghosh traces the trajectory of the silence of the subaltern primarily through the incident of Morichjhapi as a movement from the act of being silenced to the act of first resisting that silence, then to the act of appropriating that silence, and eventually to an ultimate journey of making that silence one’s own and transforming it in such a manner that it characterizes our way of knowing and being. Silence then is not opposed to language, but is something that is complementary to language: it adds meaning to language. Silence here functions as rhetoric; and we shall see that it is not treated in terms of Western binaries as something that is opposed to speech and is characterized by absence; — that silence is characterized by presence and has a life of its own; silence here is a creative force. Subaltern groups frequently use silence as rhetoric, since they are often denied the privilege of representation in mainstream narratives. Silence would often be a better tool than language, because language is the discourse of the powerful. Silence would not only resist the equation of power, but would also disrupt the very tools that have created the discrimination. Ghosh’s The Hungry Tide we have a journey from enforced silence to creative and collaborative silence. Amitav Ghosh's novel The Hungry Tide, explores the challenges faced by cosmopolitans seeking to make an ethical intervention in a subaltern space. By dramatizing the encounter between bourgeois characters and the traumatic history of people inhabiting the Sundarbans region of Bengal, Ghosh suggests that an unreconstructed cosmopolitanism is incapable of addressing social injustices; to effect any positive change, the cosmopolitan must undergo a transformation. 33 The author of The Hungry Tide also insists that poor be heard, and that make the author to create a character like Fokir. It is Fokir’s voice through other characters which is able to challenge western thinking and provoke reform. Perhaps, this is the point of entry of ‘Subaltern studies’ in the novel. This contentious claim is most clearly made in Guha’s ‘Introduction’ to the Subaltern Studies. The novel also says about the life of the refugees, who can be considered as marginal group members. Their sufferings in the tide country have been narrated deeply by Ghosh and that narration gave us a thought about the rights of refugees. The speeches given by the refugee mother Kusum may considered as the mind of the author about the settlers of the tide country after the partion. There is an incident in which the settlers calls the refugee camp as a prison all these give the reader a clear cut evidence that the elite class members in that place were considered the refugees as invaders. Ghosh’s novel is intended to leave resounding propositions in the minds of his readers. It represents the political darkness in India at the period of post – partion. It is the mobilization of the comfortable western elite into action that Ghosh is aiming to encourage through his novel. We can interact with the subaltern world though the eyes of the characters and the related incidents. They are confronted directly with impoverished subaltern voices. It is Fokir and Kusum who shows subaltern characters more. Ghosh’s message in a sense is powerless without the subaltern voices of Fokir. The refugees from Bangladesh are thus the oppressed subalterns whose voices have been silenced. Their indifferent existence in the society has proven them as subaltern identities. The tragedy of Morichjhapi carnage remained unheard and unnoticed.Ghosh has eloquently re read 34 the history of the subaltern which is a very essential and successful step of studying the subalterns. 35 Works cited Ashcroft, Bill, Gareth Griffiths and Helen Tiffin . eds.Post – Colonial Studies: The Key Concepts, London: RoutledgePublication.print. 2000 215- 219 Choudhury, Bibhash. Amitav Ghosh – Critical Essays. New Delhi: Asoke .2009. Print Ghosh, Amitav. The Hungry Tide. Delhi. Ravi DayalPublisher.print. 2008. Maher ShamdhanShital, “Refugees as ‘the subaltern’ in The Hungry Tide”. criterion.com. The Criterion: An international Journal in English vol. 3 Issue 3. September 2012. 2-4. Web. 7 January 2013. Spivak, Gayathrichakravorthy.“Can the Subaltern Speak?” 1988. personal .psu .edu: 24 - 28 Web. 7 January 2013. Suresh, Saravana R. “Post Modern Traits in the Novels of Amitav Ghosh”, thecriterion.com.The Criterion: An international Journal in English vol. 2 Issue 2. June 2011. 1- 4.web, 7 January 2013.