New Realisms (1)

advertisement

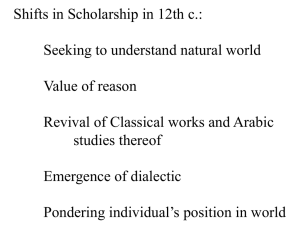

The History Play Britain’s ‘Serious’ Drama The (Royal) Court 1904-07 Harley Granville-Barker The Royal Court 1956-65 George Devine Post-War Britain: Context Internal Politics: Post-war Labour government (1945-51) followed by Conservative rule (1951-64); post-war consensus on the welfare state (health and education) External Politics: End of Empire (Suez Crisis, 1956), Cold War (nuclear threat), Soviet Invasion of Hungary (1956) Economy: growth and affluence (after rationing), rise of the consumer society (including a ‘young’ market) Culture: popularity of the monarchy (Coronation, 1953), television (‘mass culture’), American influence (Hollywood, rock & roll, jazz...) Post-War Theatre: Context The Arts Council (1945) London opening of Beckett’s Waiting for Godot (1955) Brecht’s Berliner Ensemble’s first visit to London (1956) Two new companies: English Stage Company, dir. George Devine (at the Royal Court Theatre from 1956) Theatre Workshop, dir. Joan Littlewood (touring from 1945; at Theatre Royal from 1953) Theatre Context: 1956 The English Stage Company: The ‘right to fail’ The ‘Angry Young Men’ ( ‘New Wave’, ‘Kitchen-Sink’) A theatrical revolution...? ...Or an ‘English’ reaction against continental influences and homosexuality? (see Rebellato, 1999) Political and Cultural Context: 1968 May Events in Paris Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia Anti-Vietnam War Demonstrations Assassination of Martin Luther King Anti-imperialist campaigns in Latin America (Che Guevara murdered in 1967) Enoch Powell’s ‘rivers of blood’ speech (British troops sent into Northern Ireland in 1969) Women’s Liberation Movement: Germaine Greer’s Female Eunuch and Kate Millet’s Sexual Politics published (Abortion Law Reform Act passed in 1967) Theatre Context: 1968 End of theatre censorship Rise of a ‘counterculture’ (to the left of Labour: committed to radical change) A belief in collaborative production processes and reaching wider audiences Non-traditional venues: arts labs and studios / pubs, working men’s clubs, community halls... Open attitude to form: non-illusionistic theatre, ‘avant-garde’ or ‘agitprop’ State-of-the-nation plays which were incorporated into mainstream venues (NT, RSC, regional theatres) New Writing ‘Waves’ Post-1956: John Osborne, Arnold Wesker, Harold Pinter, John Arden, Edward Bond, Ann Jellicoe, Shelagh Delaney Post-1968: Caryl Churchill, David Hare, Howard Brenton, David Edgar, Trevor Griffiths... 1980s: feminist playwrights (Sarah Daniels, Timberlake Wertenbaker, Bryony Lavery...) 1990s: Sarah Kane, Mark Ravenhill, Anthony Neilson, Gregory Burke, David Greig... 2000s: debbie tucker green, Simon Stephens, Lucy Prebble, Dennis Kelly, Laura Wade, Roy Williams... Political Theatre Forms Reality Verbatim Documentary Fiction History plays ‘Faction’ Satire Imagined worlds The History Play A traditional genre: Renaissance (e.g. Shakespeare), 18th century (e.g. Schiller), 20th c. (e.g. Shaw, Brecht) Post-1968: ‘radical’ (Peacock), ‘oppositional’ (Palmer) or ‘revisionist’ (Berninger) history plays, in synergy with new historiographies (e.g. Marxist, feminist) Beyond biography and domestic realism Against seeing the past as divorced from the present ‘Old’ and ‘New’ History (Palmer) ‘Old’ History ‘New’ History Chronology Time shifts, anachronisms Objectivity Interpretation Political and military events ‘Hidden’ histories Individual Collective Focus on the powerful Focus on the ‘losers’ Dominant men Women + Marginal groups Eurocentric viewpoint Post-colonial histories Brenton’s History Plays The Churchill Play (1974) Weapons of Happiness (1976) Howard Brenton (b. 1942) The Romans in Britain (1980) Brenton’s History Plays • • • • • • Paul (2005) In Extremis (2006) Never So Good (2008) Ann Boleyn (2010) 55 Days (2012) #aiww: The Arrest of Ai Wei Wei (2013) In Extremis (2006) First performed at the University of California, Davis, in 1997: an ‘Enlightenment play’ Revised version at Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre (2006, 2007) Twelfth-century love story of Peter Abelard and his pupil Heloise: ‘ahead of their time’ Aristotelian logic as a challenge to Christian theology In Extremis: Summary Act 1: The rise of Peter Abelard as a philosopher in Paris and the beginning of the passionate relationship with his pupil Heloise, then only seventeen years old but his intellectual equal. Abelard becomes a dangerous figure because he preaches the application of Aristotelian logic to theology and the lovers cause scandal with their sexual encounter in the countryside. Abelard is convinced that understanding faith will make it stronger, but Bernard (with the Church’s hierarchy) thinks his teachings “will only weaken belief” (35). Eventually, Abelard’s enemies inform Heloise’s uncle, Fulbert, about the affair and the couple exile themselves in Abelard’s family farm in Brittany, where their son Astralabe is born and looked after by Abelard’s sister, Denise. Heloise, who feels strongly against marriage, tells Denise: “Peter and I aren’t a family. [...] We’re warriors. Philosophical warriors. We’re fighting in a war of ideas” (46). Act 2: Abelard attempts –unsuccessfully– to reconcile with Fulbert by marrying Heloise in secret (marriage, although allowed, would spoil Abelard’s prospects as a cleric). Threatened by Fulbert’s cousins, the couple seek refuge in the convent of Ste Marie Argenteuil and even make love on the altar, but when Abelard returns to his lodgings he is castrated by the Fulbert gang. Abelard then takes the vows and asks Heloise to do the same. Act 3: Twenty years later, Bernard is planning to accept a public disputation with Abelard only to manipulate it (by getting the bishops drunk before the meeting). Abbot Abelard and Abbess Heloise, who now very rarely see each other, are excited by the prospect of the debate. When the day comes, however, Bernard accuses Abelard of heresy and the latter remains silent on realising that the Council has been fixed. Abelard is excommunicated and then pardoned, but he falls ill. He finally gets the opportunity to debate with Bernard, in private, and in the next scene he is brought to die (offstage) in Heloise’s arms. After his death, Heloise defiantly tells Bernard “You’ve lost, you know” and shows him a Penguin copy of hers and Abelard’s letters “eight hundred and fifty years from now” (89). In Extremis: Critical Response British critics compared the play favourably with the last account of this twelfth-century love story seen in London: a 1970 play by Ronald Millar (one of Margaret Thatcher’s speech writers) famous only for “the legendary nude scene by Diana Rigg and Keith Mitchell” (Paul Taylor in the Independent). If some reviewers were expecting even more controversy from the author of The Romans in Britain, this is not what they found: “In Extremis [...] is itself not without a certain shock factor: there’s vomiting, masturbation and a lusty bit of genital mutilation”, wrote Robert Shore in Time Out, “but it is still pretty tame by comparison with the Globe’s current production of Titus Andronicus”. What Brenton offered instead, according to Evening Standard’s Fiona Mountford, was “an admirable equilibrium [of] the elements of sexual desire, non-conformism and philosophical ideology that fuelled the couple’s relationship”. Michael Billington in the Guardian also saw balance in the presentation of Abelard and his nemesis, the ascetic but influential monk Bernard of Clairvaux, who “supposedly representing everything Brenton’s deplores [...] emerges not only as the most gripping figure but also the real revolutionary”. Bibliography Berninger, Mark. ‘Variations of a Genre: The British History Play in the Nineties’. Anglistik & Englischunterricht 64 (2002): 37-64. Holdsworth, Nadine. Joan Littlewood. London: Routledge, 2006. Itzin, Catherine. Stages in the Revolution: Political Theatre in Britain since 1968. London: Methuen, 1980. Megson, Chris (ed.) Modern British Playwriting: The 1970s. London: Methuen, 2012. Nicholson, Steve (ed.) Modern British Playwriting: The 1960s. London: Methuen, 2012. Palmer, Richard H. The Contemporary British History Play. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1998. Pattie, David (ed.) Modern British Playwriting: The 1950s. London: Methuen, 2012. Peacock, D. Keith. Radical Stages: Alternative History in Modern British Drama. London: Greenwood, 1991. Rabey, David Ian. English Drama Since 1940. London: Longman, 2003. Rebellato, Dan. 1956 And All That: The Making of Modern British Drama. London: Routledge, 1999. Reinelt, Janelle. After Brecht: British Epic Theater. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994. Roberts, Phillip. The Royal Court Theatre and the Modern Stage. Cambridge: CUP, 1999. Shellard, Dominic (ed.) British Theatre in the 1950s. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2000. Taylor, John Russell. Anger and After: A Guide to the New British Drama. Pelican Books, 1963. Wandor, Michelene. Look Back in Gender. London: Methuen, 1987.