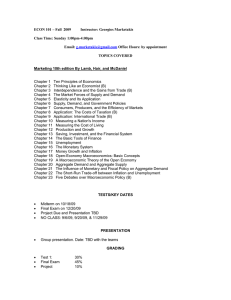

Monetary Policy in the Global Economic and Financial Crisis1 First, I

advertisement

1 Monetary Policy in the Global Economic and Financial Crisis1 First, I should say that this lecture is my own personal view. I mean this in two ways. Of course, it is not necessarily the view of the OECD or its member countries. But beyond that, some of what I say is certainly not obvious and would be disputed by others. Also, my view is coloured by the experience of North America and, especially in the 1980s, by my own experience at the Bank of Canada. Finally, I am going to talk almost always about the three major currencies: the American dollar, the euro, and the Japanese yen; and about the corresponding central banks: the Fed, the ECB and the BoJ. This has been a global crisis and surely the response has been dominated by the globally important players. This means I won’t talk much about: the euroarea crisis, the UK, Switzerland, or Canada and Australia. All have a role in the story. The euro crisis has to some extent driven ECB policy, especially so-called “unconventional” policy. If the euro fails, of course, then the euro-area crisis might prove to be the most important facet of the global financial crisis. The UK and Switzerland are major financial centres and so have been near the heart of the financial crisis, but they are relatively small economies which don’t have systemically important currencies. Australia and Canada are countries that sailed through the crisis pretty much unscathed, and so presumably have lessons to teach us. But again, they are small economies and currencies. The lecture will be divided into three parts. First is a brief history of monetary policy and theory. This is a bit of a detour, but it shows where monetary policymakers—and myself— stand when we are analysing the crisis. Second is the monetary policy response to the crisis. And third is my speculation on the future of monetary policy after the crisis has passed. 1 Robert Ford, Deputy Director of Country Studies, Economics Department, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. The views expressed are those of the author, and not necessarily those of the OECD or of its member countries. Preliminary: please do not quote. 2 1. The recent history of monetary policy and theory I want to begin by discussing the history of monetary policy in action and the relevant economic theory that has accompanied it. Again, much of this is disputable, and there are certainly other interpretations out there. Also, I will leave the impression that monetary policy is a fairly mechanical exercise in the obvious application of economic theory as it was understood at the time. This impression is false. Monetary policy operates in something of a fog, and this is true today more than ever. How the levers of policy affect financial markets, the real economy and prices is only imperfectly understood. Milton Friedman spoke of “long and variable lags”, by which he meant that central banks have no precise idea of the effects of their actions. These lags require that central bankers peer into the future, and the future is somewhere between hard and impossible to predict. And much else is going on besides monetary policy, making it difficult to figure out what influence policy has had, even after the fact. We are still arguing about the Great Depression and about the stagflation of the 1970s. And we will be arguing about the Great Recession for many years to come. Policy From the end of WW2 until 1970s, monetary policy in the major currency areas had been governed by the so-called Bretton Woods framework, which featured theoretical convertabilty to gold (at $35 to the ounce), a system of more-or-less fixed exchange rates, capital controls, and the US$ as the reserve currency. In the early 1970s, this system broke down as capital flows increased, US monetary policy began to lose control. and the US severed the formal link between the $ and gold. A new international monetary system emerged, one that to this day has not been very carefully thought out. It features floating exchange rates and much free-er capital flows. One result is that individual countries have more scope—or, put differently, more responsibility—to use monetary policy to stabilise their economies at full employment. The 1970s were characterised by “stagflation”: the combination of poor economic performance and rising inflation. At the time, stagflation was poorly understood, and gave rise 3 to various “heterodox” policy innovations, such as wage and price controls (in the US) and suggestions (not implemented) for things like “tax-based incomes policies”. The situation was badly clouded by the first oil price shock. In retrospect, we now believe that stagflation was due to a negative supply shock—falling productivity growth and an increase in the NAIRU. The implication is that monetary policy reacted in the wrong way: it tried to restore economic activity to its old path, which was impossible and resulted in rising inflation. The correct response would have been to tighten policy to bring aggregate demand into line with the lower output path. By the end of the 1970s, this lesson had been learned, and monetary policy tightened aggressively, especially under Fed governor Paul Volker. The result was a substantial recession and lower inflation. At the same time, central banks had to find a new policy framework, and some settled on money targeting of one sort or another. In the event, the money targets proved unstable and targeting them was thus of only limited practical use. By the mid-1980s inflation targeting was gaining ground. The logic is that central banks, ultimately, can control only inflation and that over time low and stable inflation maximises economic prosperity. By the end of the 1980s a number of central banks were adopting IT. And, it seemed to be a success. The period from the late 1980s to 2006 became known as the Great Moderation. By and large, growth was strong and inflation moderate. Even emerging market countries, notably Brazil, successfully adopted IT to get inflation under control without obviously hurting growth. Of course, the Great Moderation ended in the Great Recession, which we are still in. This has cast doubt on inflation targeting and raises the question of what might replace it, if anything. There is a parallel intellectual history to go along with the evolution of monetary policy. By the end of the 1960s, practical policy making theory was characterised by what I will call the Keynesian Synthesis: economic activity is driven by aggregate demand; aggregate demand can be affected by monetary and, especially, fiscal policy; macro policy faces a tradeoff between 4 inflation and unemployment (or economic growth) given by the Phillips curve. It is this last point that made stagflation—both unemployment and inflation rising—so puzzling. During the 1970s, this framework was significantly altered by the work originally done by Friedman and Phelps on the vertical Phillips curve and, a bit later, by people like Lucas, Sargent and Wallace on so-called rational expectations. The essence of the matter is that policymakers don’t face an inflation-unemployment trade off at all. Rather, the NAIRU is determined by “real” factors, beyond the control of monetary policy. Any attempt to hold unemployment below the NAIRU just increases inflation but does not permanently change the unemployment rate or economic activity. Moreover, for monetary policy in particular, this model shows that “time inconsistency” yields too-high inflation if central bankers use discretion, and thus provided powerful theoretical underpinnings for rules-based monetary policy, such as money or inflation targeting. This framework was soon generalised to become Real Business Cycle theory. With RBC, demand is not the main source of economic fluctuations—supply is. And supply is beyond the influence of monetary policy. Therefore, monetary policy should not seek to stabilise output. Rather, monetary (and, it should be said, fiscal) policy should focus on avoiding disruptions to the workings of the market; that is, activism should be avoided. Again, this underpins rulesbased monetary policy. A related strand of thought is New Keynesian theory, which is associated with Fischer and Mankiw. In these models, the economy is fundamentally determined by real factors, as in RBC theory, but temporarily deviates from full-employment equilibrium because of various nominal rigidities. Multi-year nominal labour contracts lock in wages, or “menu costs” keep nominal prices from adjusting continuously. The policy prescription consistent with New Keynesian theory is flexible inflation targeting, associated with Lars Svensson, which takes transitory deviations from full employment (due to the rigidities) into account in setting policy. Inflation targeting central banks are all flexible inflation targeters in practice. In that sense, New Keynesian theory has been more influential than RBC theory among policy makers. 5 Of course, the financial crisis and the Great Recession called into question models that assume equilibrium and the policies that flow from them. 2. Let me now turn to the specific issue of the monetary response to the global economic and financial crisis. It is now widely recognised that monetary policy was too loose in the period leading up to the crisis, in the sense that output levels were, in retrospect, higher than sustainable. And policy makers knew this. Interest rates were being raised quite sharply through to about 2006. They were also well aware of possible asset price bubbles, especially in real estate and especially in the United States. At the same time, however, inflation seems to have been contained. A number of explanations have been offered for this puzzle, none of which seem to me to be fully satisfactory. Perhaps the answer is that inflationary pressures were building, and had the Great Recession not occurred we would have found ourselves in a high inflation environment by end-2000s and needing to repeat the Volker experience of the early 1980s. But at the time, there was hope that the monetary policy tightening would be enough to stabilise inflation without requiring such tough medicine. The crisis itself, or at least its suddenness and severity, was surprising. In 2006, US house prices had started to fall. It was generally thought that this would depress activity, but not generate a big recession. Indeed, some welcomed the downturn in house prices in 2006 as desirable correction heralding a soft landing. In 2007 the outlook started to deteriorate, but growth was still positive. In the spring of 2008 Bear Stearns failed, but this caused little market disruption, providing some cause for optimism that the situation was manageable. In September 2008, of course, the collapse of Lehman Brothers and AIG triggered a global financial crisis that soon became the Great Recession. Conventional monetary policy 6 The policy response to the crisis was a complicated, and sometimes hesitant, combination of monetary and fiscal policy easing, and various emergency measures to shore up the banking sector. I will focus here on the monetary policy response. These next slides show the interest rate response—that is, the “conventional” monetary response—to the impending collapse. You can see the run up in official rates prior to the crisis, and then the very sharp cuts in late 2008 and into 2009. Interest rates in all three major monetary zones were almost immediately cut to practically zero. I would judge this an entirely conventional and appropriate response to what was undoubtedly the largest financial shock since the Great Depression. These slides show the corresponding market interest rates. They too had risen in the run up to the crisis, and then fell very quickly to very low levels. In this sense, the monetary policy transmission mechanism worked: official rate changes quickly affected market rates. In another sense, however, the transmission mechanism did not work very well: low market interest rates have not translated into economic recovery, even today. Why has policy not seem to have worked? On the one hand, the slow recovery was widely predicted. Historically, recessions caused by financial crises had been long, and there was little reason to think this time would be much different. It has not. Why are financial recessions long? First: they are preceded by increases in debt and accompanied by sharp falls in asset prices. By 2006, household debt had reached record proportions in many countries, and the recession triggered a sharp fall in house and equity prices—household wealth. So, as households reestablish their finances, consumption is not likely to be a source of growth. Second: banks are weak, in the sense that their capital is diminished, and their assets (loans) are less solid, because of bad investments of various sorts in falling housing markets. To rebuild, banks restrict their lending. Banking supervision has aggravated this. Since the proximate cause of the Great Recession was weak banks, regulators have been correctly insisting that banks 7 build up their capital. Thus, even though banks can fund themselves very cheaply, they are not so interested in taking on more credit risk. There are other reasons for the long recession, none of which are specifically related to its financial genesis, and some have nothing to do with monetary policy. First: One of the channels for expansionary monetary policy is exchange rate depreciation. But since all major currency areas are pursuing very expansionary policy, there has been remarkably little movement in exchange rates. This does not necessarily mean that global monetary easing should not have been effective. Nor does it mean that countries are wrong to ease: a country that did not would see its exchange rate appreciate. Second: Fiscal deficits expanded sharply during the Great Recession, and now governments are in the position of having to consolidate. (See my other lecture). Third: Business investment has been weak, and this is usually what pulls economies out of recession. To some extent, this might be explained by the shut-down of asset markets after Lehman, as many corporates raised money on these markets rather than through banks. Yet, by all accounts corporates now have plenty of internal cash and can once again raise money at very favourable rates. Fourth: The famous “zero lower bound”. Nominal interest rates cannot go much below zero, because otherwise it is better for asset holders to hold cash, which has a zero interest rate. The ZLB is not specific to a financial crisis, but would appear to limit on conventional monetary policy. Since inflation is very close to zero, real interest rates cannot be very low. For example, with inflation at about 1%, a zero nominal interest rate means a real rate of only -1%, when perhaps a real rate of -3% or -4% is needed to spark a strong recover. Policy rates could of course fall below zero: central banks could pay people to take money. This would wipe out money markets—why pay costs to transact there when you can make money by doing it through the central bank? It would also not push market interest rates below zero, and so real market interest rates might still be too high. 8 Fifth: Finally, it may be that the recession lowered the “natural” rate of interest—the rate at which the economy is in full-employment equilibrium. The natural rate is often identified with long-term growth, and perhaps the recession has been protracted enough that, for this purpose, we are now in the long term. If the degree of monetary policy stimulus depends on the difference between the natural rate and the actual rate, a fall in the natural rate cuts stimulus, all else equal. Conventional Unconventional monetary policy Concerns about the weak recovery soon led central banks to use so-called “unconventional” monetary policy, which I will identify with the term Quantitative Easing. There are many definitions of this term, and the associate term “quantitative easing”. Because QE is now the cutting edge of monetary policy, I want to spend some time on it. This table gives the QE highlights of the first year or so after Lehman. A common way to illustrate QE is the expansion of the central bank balance sheet, as in this chart. Indeed, some economists define QE as an expansion of the central bank balance sheet. Both the Fed and the ECB greatly expanded their balance sheets following the crisis. The BoJ had done the same much earlier, when Japan had its crisis, but has done less more recently, perhaps out of concern that its balance sheet is already very large. QE is basically large purchases of a range of assets by the central bank, in exchange for money (or reserves at the central bank). Put this way, QE is not particularly unconventional. Central banks have long operated through open-market operations: exchanging central bank liabilities (money) for private sector assets. What makes QE different? Probably three things: the size of the transactions; the type of assets acquired; and the duration of the operation. The size can be seen from the chart. In terms of numbers, since the crisis the Fed has purchased gross assets worth 22% of US GDP, Japan 37.3% of GDP, and the ECB only 3.5% of GDP. Not all asset purchases have expanded the central bank balance sheets, as some were offset by sales or reversed. But these are large numbers. 9 This table shows the composition of these asset purchases. The Fed has bought LT gov’t bonds and private-sector assets (mortgage backed securities). The ECB has also bought private assets (covered bonds), although it has also bought government debt on the secondary market. The BoJ has bought almost exclusively government debt, and most of that at the short end. In the US, about $700 billion of the long-term bond purchases were part of “operation twist”: that is, they were purchases not with money but with shorter-term debt. The ECB claims to have “sterilised” the SMP—that is to have sold some other form of debt to keep the money stock unchanged. If so, SMP is in this respect like “operation twist”. However, there has recently been big news in Japan. About a month ago, at its first policy meeting following the installation of the new Governor, the BoJ announced a huge change in its QE policy. In the next two years, it plans to double the BoJ’s balance sheet, bringing it to some 60% of GDP. This is far beyond anything a large country has done. Also, it is extending asset purchases to long-term government bonds (and a bit of private sector stuff). What is the logic behind QE? QE, or unconventional monetary policy more broadly, has been used for two reasons: to compensate for a “damaged” or “impaired” monetary transmission mechanism; and to increase monetary support once the policy interest rate has fallen to zero. Trichet, the former governor of the ECB, has emphasised that the ECB began unconventional monetary operations well before its intervention rate fell to zero. Some of the BoE operations are designed to get credit to certain groups—small businesses—that are seen as suffering particularly from an impaired transmission mechanism. Conventional monetary policy involves buying very short-term assets in exchange for money. This could stimulate activity in two ways. First, it drives down the short-term rate, which tends to pull down long-term rates. The interest rate charts I showed earlier illustrate how this worked. Lower long-term rates are supposed to spur activity by, for example, lowering the cost of capital for firms, who will then increase capital spending. Second, according to the money multiplier it should increase broad money, which is the counterpart of increased bank lending. 10 But now the short-term rates are now at the zero lower bound, and this policy option has run out of room. QE is an attempt by central banks to reduce longer rates further by buying up longer-term assets and locking them away for a while. How this works has been divided up into a number of “effects”: One: the portfolio balance effect. This is just supply and demand. If the various assets are not perfect substitutes, then buying up one type of asset raises its price, or lowers the interest rate. This means, by the way, that the BoJ approach is likely to be the least effective, as short-term government debt is a relatively close substitute to money itself. Two: the signalling effect. By buying large quantities of longer-term debt, a central bank demonstrates a commitment to hold down short rates longer; for one thing because it is now exposed to large capital losses if interest rates rise soon. Three: the liquidity effect. Central bank purchases increase market transactions and may reduce liquidity premiums that asset holders demand in crisis times because of the possible lack of a counterparty to sell to. And how effective has QE been? This is of course the subject of much research these days. The bottom line from event studies seems to be that individual episodes of QE have pushed down interest rates, at least for a while. They have not increased broad monetary much; that is, the money multiplier has dropped to almost nothing. It is less clear that QE has done much to stimulate spending, but that is difficult to judge because we have little way of knowing what would have happened without QE. Judgements on this point tend to come from model simulations, which are not exactly the same thing as empirical evidence. Unconventional unconventional monetary policy In addition to QE, central banks have tried to increase the effectiveness of monetary policy in a number of other, more or less unrelated ways. 11 First: “Forward guidance”: To bring down longer-term rates, some central banks have made announcements to convince markets that short rates will be held down for a long time. The Fed first announced it would hold rates down “for an extended period, then for specific periods, and most recently until the unemployment rate has fallen to 6.5%. Just this spring, the BoJ announced, for the first time, an inflation target of 2%, to help guide expectations away from the long-entrenched deflation. This sort of thing—the central bank making announcements to influence expectations—is actually commonplace. Some IT central banks have tried to institutionalise it by providing interest rate projections as part of their monetary policy announcements, and by publishing decisions and meeting minutes. Does it work? There is lots of evidence that, in general, markets respond to central bank announcements. There is less evidence that interest rate forecasts have much effect. As a counterexample, in Sweden, interest rate expectations have diverged systematically from the Riksbank’s published forecast. There is little evidence that the Fed’s forward guidance has had much effect. The lack of effect could be traced to the success of inflation targeting. Although the Fed does not officially target inflation, markets have long believed it would not tolerate inflation above 3% or so. Markets have surely been correct in this belief. Promising to hold down interest rates no matter what is, for an IT central bank, time inconsistent: as markets tighten, it will have to raise interest rates again. Second: “liquidity operations”: since the beginning of the crisis, central banks have been providing large amounts of liquidity—lending money—to the financial sector. To some extent, this is like lender-of-last-resort operations: the central bank lends to solvent banks to overcome a temporary cash shortage. Such shortages became almost universal following Lehman and the collapse of interbank and short-term paper markets. This is not normally considered monetary policy at all, but when it is extended for so long the difference becomes less evident. The ECB has lent some euro 1 trillion through its Long-term Refinancing Operation (LTRO), ostensibly to reduce risk premiums and thereby bank lending rates. This looks a lot like monetary policy. 12 Third, subsidies to specific activities: to some extent, Fed purchases of MBS can be thought of as a sort of industrial policy to increase housing investment. The UK has introduced its own programme to direct lending to the housing market and small firms (Funding for Lending). Fourth: “Helicopter money”: no central bank has announced any such thing, but it has come up in policy discussions. Helicopter money is paying for government spending by printing money, rather than issuing debt. It could equally be called “money-financed fiscal expansion”. It could be engineered by a combination of debt-financed public spending and an open-market operation in which the central bank buys government debt in exchange for money. When put this way, it looks quite a lot like what the Fed (with its purchases of government debt), the ECB (with its purchases of government debt with the SMP), and the BoJ (with its purchases of Japan government bonds and its lending to banks, which have used the money to purchase Japan government bonds) have all done. All three central banks can deny that this is really helicopter money. They all intend to reverse these operations at some point, but this could be described as first doing a helicopter operation and sometime later doing the reverse (a vacuum operation?). Risks of monetary expansion Let me end this part of the talk by noting that there are downsides to sustained and extreme monetary easing. These have been highlighted by Bill White and Ragu Rajan, although as far as I can tell nobody has actually recommended raising rates at this point. First, low interest rates are a subsidy to borrowers. Such a subsidy would be expected to lead to poor resource allocation—such as bad capex decisions. Symptoms of this might include “zombie” firms, evergreening bad loans, and increased leverage (which is cheap). For governments, it may take pressure off fiscal retrenchment, as even a very high debt burden seems affordable. Japan has gross public debt of some 230% of GDP, but as the interest rates on it are very low, it has been sustainable for some time. It is also a tax on asset holders. This is thought to spur a “search for yield”; that is, a shift in portfolios towards ever more risky assets. 13 One symptom of this is the large capital inflows into emerging market countries—Brazil is the best known case—which can be destabilising. Second, with QE central banks, and ultimately taxpayers, are taking on more risk. This is not necessarily a bad thing for the economy (it depends…), but given already difficult fiscal positions it could turn out badly. So far, central banks don’t seem to have lost money on these operations, but this could easily change. 3. The future of monetary policy This has 2 parts. First, what is policy actually going to do next? Second, how will the experience of the Great Recession influence the monetary policy framework in the future? What to do next. It seems to me that policy will have to stay very supportive for the time being. And we have pretty much run out of ideas for “unconventional” policy, except for outright helicopter money. A trickier issue is exit. As economies recover, interest rates will have to rise and QE unwound. For the latter, central banks will have to sell much of their accumulated assets. First is the issue of timing: it seems likely to me that central banks may withdraw stimulus too slowly, which will result in higher inflation and perhaps even require a monetary-policy induced recession, as happened under Volker at the end of the 1970s. This could arise for at least three reasons: (i) after years of high employment and poor growth, there will be pressure to avoid cutting the recovery short; (ii) with IT discredited, central banks may start to run policy off real variables, such as the unemployment rate, and they may underestimate the natural rate of unemployment, as happened in the 1970s (I will return to this); and (iii) deliberate inflation to help reduce the real value of the public debt. Second is the issue of how asset markets will react to the central bank sell off. I have little insight to offer here, because I don’t know of any relevant similar episode. Maybe it will go fine, maybe not. Will IT survive? 14 The Great Recession has called the monetary policy framework—and especially Inflation Targeting—into question. So, will IT survive? There are three answers: (i) Yes. Lars Svensson is probably the most vocal defender of this position. IT did just fine and the causes of the crisis are to be found in poor financial supervision, especially in the US mortgage market and in the European banking sector. So far no IT central bank has announced that it will no longer use the framework. For me, one reason to keep IT is the exit problem: even more than in the early 1970s, we have little idea about where potential output is, or what the natural rate of unemployment is. What the 1970s taught us is that especially in such a situation we should not ignore the signal from inflation. (ii) No. IT failed to prevent the largest crisis in 80 years, and arguably caused the crisis because central banks, seeing no inflation, ran policy too loose. This resulted in excess liquidity which, in the event, flowed into real estate and ever more dangerous financial product that were needed to keep that money on the move. This judgment raise the question: if not IT, then what? Let me say here that, so far, the search has not been very imaginative. The alternatives which are now under discussion are fine, and one or more of them may prevail. But in many senses they amount to fine tuning, and are not on the scale of the shifts we saw following the collapse of Bretton Woods or after the Great Stagflation. In particular, it is not clear that any of them would have performed better in the boom and the Great Recession than IT did. In that sense, unlike the previous shifts in monetary policy practice, none of these seem to be an adequate response to the challenges we face coming out of the Great Recession. There are now three major alternatives, which I won’t dwell on very long. price level targeting. Instead of inflation, monetary policy targets the price level, perhaps allowing a trend at, say, 2% a year. In rational expectations models, this is superior to IT because it generates much stronger feedback control and therefore, if it is credible (and in RE models it is always credible) it more tightly anchors expectations. If it 15 is not credible, then all bets are off. But in the end, this looks not all that different from inflation targeting, where the trend in the level target is the inflation rate target. Nominal income targeting. Here, monetary policy targets nominal GDP. The idea is that inflation and real GDP tend to move in the same direction, and so monetary policy stabilises a bit of both. This is not so different from so-called “flexible” inflation targeting, in which deviations of GDP from potential are taken into account. The difference is that under flexible inflation targeting the weight on GDP declines over time to nothing. NIT is subject to many criticisms: for example, nominal GDP is published only with a lag and is often significantly revised, so it is not so clear what the target is. But my worry is that it assumes that all shocks are demand shocks: that is when you get the positive correlation between inflation and real GDP. As we saw in the 1970s, this is not always true. real targets. This is, in a sense, a return to the 1970s. The Fed has announced that it will keep monetary conditions loose until the unemployment rate has fallen to 6%. This is not quite a target, and I’m sure the Fed is betting that inflation will not turn up before then because they are sure the natural rate of unemployment is well below 6%. But as the Great Stagnation drags on, there may be increasing calls for monetary policy to fight unemployment more directly, even to the point of targeting something like an unemployment rate. (iii) Sort of. This middle way is my guess of what will happen. On this view, IT was fine as far as it went, but was insufficient. Destructive imbalances grew—and this is very obvious now and was to some extent obvious even at the time—and monetary policy did not react properly. At a minimum, monetary policy also has to take into account some notion of financial stability and central banks will have to lean against things like asset price bubbles. The Greenspan doctrine of waiting for them to pop and then cleaning up afterwards failed. How this is exactly to be done is not clear. Even now, in some countries—Australia, Canada and Norway come to mind—central banks have been reluctant to tighten monetary policy solely to contain what appear to be, or what might turn out to be, housing bubbles. That is, they seem to 16 be focused on activity and inflation, just as before, and seem unprepared to sacrifice on that side to reduce the odds of an asset price bubble. Instead, the policy consensus seems to be forming around the combination of IT and so-called macro-prudential supervision. One way of looking at this is in terms of “instruments-targets”: you need as many instruments as you have targets. In this case, monetary policy targets inflation, and macro-prudential policy targets financial stability. What is macro-prudential supervision? It is still not very well defined, much less operational, but the idea is that some authority makes judgments about the state of the financial sector as a whole, as distinct from individual institutions, and uses tools other than traditional monetary policy to keep risk down and stability up. The sort of tools envisaged are not very different from normal prudential measures, but their application would be triggered by the overall financial situation, not the situation of an individual institution, and could be applied to all institutions, not just those judged to be weak. Some are different. For example, the idea of countercyclical capital requirements is popular among analysts, and was actually used in Spain, although this did not save its banking system. Another example might be caps on LTVs or on the amortisation period of mortgages, which would be meant to control household borrowing. There are more exotic suggestions, too. For example, some academics have proposed taxation of the use of short-term market financing, on the grounds that dependence of this sort of financing was one of the causes of the financial crisis and that it creates a sort of financialstability externality. (Those who advocate this argue that it is superior to the Basel III alternative of quantity restrictions on short-term financing. This view already seems influential in terms of the structure of monetary policy and banking supervision. The Fed has always had a lot of supervisory power, but it may become even more influential as a key player in the high-level council of supervisors that has been set up. The EU is set to move towards a “banking union”, and one aspect of this is to assign bank regulatory powers to the ECB. The UK has reformed its banking supervision structure, essentially by moving most of it to the BoE, which is now said to be the most powerful central bank in the world. 17 The international dimension Let me finish by considering the international dimension of all this. I have not talked about this very much. In effect, I have taken the view that in the post-Bretton Woods system of flexible exchange rates and capital mobility countries have the freedom and responsibility of carrying out their own monetary policy. Exchange rate movements deal with the international interactions. However, it is clear that the international monetary system has come under great strain, and that strains will continue. In the run-up to the crisis international bodies focused on so-called international “imbalances”, by which they meant large and persistent current account surpluses and deficits; notably, the US deficit and the Chinese surplus. This is illustrated on the chart here, which is hard to read but breaks down current account surpluses by type of country. It was feared that these imbalances would eventually force adjustments of exchange rates, interest rates and policies, and that these adjustments might prove disorderly. In the event, imbalances were not the cause of the Great Recession, but if the banking crisis had not occurred, they might have been. Since the crisis, the focus has shifted somewhat. Partly, this is because current account imbalances have diminished. The huge Chinese trade surplus has essentially vanished. The US deficit has narrowed, and seems likely to narrow further given the development of “fracking”. How permanent are these changes? Well, much of it is cyclical. For example, the narrowing US deficit and perhaps the Chinese surplus surely reflect the US recession and the decline in domestic demand. This will presumably be reversed. In OECD projections, the output gaps are not closed much and, as a result, there is not much change in projected imbalances. You can see on the chart that there was a once-off drop in the recession, and not much has happened since. In any case, attention has recently shifted to the effects of very easy monetary policy in advanced countries on emerging market countries. Specifically, Brazil has repeatedly argued that very easy monetary policy in the US and Europe has diverted capital flows to emerging 18 markets, raising their exchange rates and undermining financial stability. Brazil’s response has been a form of capital control, although this is to some extent disguised as macro-prudential measures. Indeed, the borderline between macro-prudential policy and capital controls is not very precise. Korea is following similar policies. Switzerland, as I mentioned earlier, has capped the exchange rate of the franc. A big part of the problem here is the sheer size of international capital movements: such movements are easily big enough to move exchange rates and are very difficult for financial systems to absorb. So this may be the future for the international monetary system. A return to selective capital controls and more direct intervention in exchange markets. And there will be damage, since capital and exchange-rate controls surely distort economic activity and will tend to reduce the advantages of international trade. In this sense, it would be better to come up with another international architecture that preserves the advantages of capital movement while controlling its bad effects. This is easier said than done. The IMF has been working on “rules” for such policies, in an effort to minimise the damage. I’m not sure how far they have got. The OECD has longstanding “codes” on capital flow liberalisation, which could also serve as a template for international rules on managing capital flows.