Chapter 5

advertisement

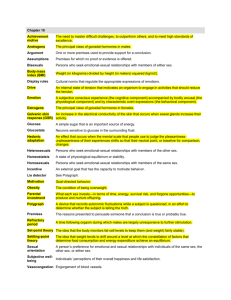

Chapter 5: Lecture Notes Premises: What to Accept and Why Chapter 5 Acceptable premises are important because even if you have the best, most elegant reasoning possible, if the premises are acceptable, then the reasoning does not matter. What does it mean to say that the premises of an argument are rationally acceptable? How might we show that they are? We are going to look at seven ways to show premises are acceptable. Chapter 5 When premises are acceptable: (i) Before you begin we need to make an important philosophical point. Govier refers to 'acceptable' and 'unacceptable premises. She doesn't want to refer to 'truth' or 'falsity' or have you say: 'Such and such is true' because whether something is 'true' or 'false' is independent of whether or not anyone KNOWS or BELIEVES it to be true or false. Think about it. (ii) It is either True or False that there is someone named Deanna sitting in a Cafe' in Graz Austria right now. But is this reasonable to believe? How can you KNOW it if you aren't there right now? Or how about whether there is life after death? It's either true or false, but how do we determine which it is? Acceptability is a much better concept to start with since it puts this more epistemologically complex concept of 'what is truth?‘ aside for now ("epistemology" is a branch of philosophy dealing with different theories of knowledge). Chapter 5 Premises are acceptable if: (1) They are supported by a cogent subargument. This means that if the conclusion of a cogent subargument is a premise in another argument, then there is every reason to accept it as a premises. (2) The premises are supported elsewhere. Elsewhere there could be another cogent argument that the author or some other author has already established as cogent. Chapter 5 (3) The premise is know a priori to be true. A priori statements are the kind of things a person could know independent of experience or before experiences. It is contrasted with the term a posteriori. Statements that are knowable a posteriori require experience. Consider the following claims, the first is a priori and the second a posteriori. (i) (ii) Bachelors are unmarried males. Chuck D. is a bachelor. (i) is knowable with out experience, but to know Chuck D. is a bachelor requires experience in the world. Chapter 5 (4) A premise is acceptable if it is a matter of common knowledge. If just about everyone knows or understands that a premise is true, then the premise is acceptable. Some simple examples: (i) (ii) (iii) (iv) (v) The flu is contagious. You cannot take a train from London to Los Angeles. Cats have claws Motorcycle riders are safer while wearing helmets. Hitting a curve ball from a Major League pitcher is hard. Chapter 5 When it comes to common knowledge we have to be careful because common knowledge can change given the times and what kind of events are occurring in the world. So, must people that live near Chicago, know that the Cubs last won a World Series in 1908. But few know when the last time the Los Angeles Dodgers won. If you were near Los Angeles, you would be more likely to find someone that knew the Dodger last World Series win was 1988. Chapter 5 (5) Testimony -- under some conditions, a claim is acceptable on the basis of a person’s testimony. There are three main factors that will undermine our acceptance of testimony as reliable. (i) (ii) (iii) The claims made are implausible The person making the claim or other source is unreliable The content of the claim goes beyond the experiences or competency of the testifier A lot of things give rise to when and how we accept testimony and how to govern its acceptability. Chapter 5 (6) Appeal to a proper authority Sometimes we have to take the word of a proper authority with respect to the acceptability of a premise. If a logic professor told you that a particular argument was deductively valid, you can trust that because she is a proper authority on the validity of arguments. This same logic professor, however, may not be an authority on the exports of the state of Florida, and cannot explain if an income tax would increase tax revenue or not. Authorities must be proper to make premises acceptable. Chapter 5 (7) The last method of accepting premises is different from the rest. We say that we accept a premise provisionally or conditionally. You might find an argument to pass both the (R) and (G) conditions for cogency, but are uncertain about the acceptability of the premises. You can provisionally accept the premises and thus provisionally accept the conclusion and cogency of the argument. Chapter 5 Summary of the acceptability conditions: A premise in an argument is acceptable if any one of the following conditions is satisfied: (1) It is supported by a cogent subargument. (2) It is supported elsewhere by the arguer or other person, and this fact is noted. (3) It is know a priori to be true. (4) It is a matter of common knowledge. (5) It is supported by appropriate testimony. (6) It is supported by an appropriate appeal to authority. (7) The premise is not know to be rationally acceptable, but can be accepted provisionally for the purpose of the argument. Chapter 5 When premises are unacceptable: Premises are not acceptable or unacceptable in many ways, and we are going to look at five general ways. (1) The premise is easily refuted. For example: (i) (ii) Every male golfer is better than every female golfer. All politicians are corrupt. Both (i) and (ii) are easily show false. Michelle Wie defeated lots of men in a golf tournament. Abraham Lincoln or some other politician are not corrupt. Chapter 5 (2) Claims that know a priori to be false. There are some statements that are know to be false by the very understanding. For example, (i) The triangle did not have three sides. (ii) The square was not a rectangle. (iii) He was both awake and asleep at the same time. All of these statements are false and are know to be false without having to have any experience. We can reason that they cannot be true by their very nature. Chapter 5 (3) Inconsistent premises make the premises unacceptable. If the premises of an argument directly or indirectly contradict each other then one of them is unacceptable. Imagine that in the course of a long argument the following two statements are made: (i) (ii) James is always mean to Judy. James kindly helped Judy with her logic homework. Now it is clear that if (ii) is true, then (i) is false. This kind of contradiction is implicit because we don’t have a claim and its direct opposite like: James is not always mean to Judy, which would be a direct contradiction. Chapter 5 (4) Vagueness or ambiguity can give rise to unacceptable premises. For example, (a) Aggressive behavior is rampant in young boys. The fact is that the terms aggressive behavior, rampant, and young are vague and make it so that this premise is not acceptable in its current form. In order for us to accept a premise it has to be presented with clear language that is neither vague nor ambiguous. Chapter 5 (5) The fallacy of begging the question occurs when the premises are no more acceptable than the conclusion. Sometimes this is referred to as circular reasoning or circularity. To beg the question in the logical sense occurs when a premises is not acceptable because it states or assumes the conclusion. The following argument begs the question: The killing of innocents is wrong. Abortion is the killing of innocents. Therefore, abortion is wrong. Chapter 5 The reason it begs the question is because the first two premises are in need of support in the same way that the conclusion does. In political contexts begging the question means to avoid a topic or question. This is not the sense for which we are using begging the question. Chapter 5 Summary of Unacceptable Conditions (1) One or more premises are refutable on the basis of common knowledge, a priori knowledge, or reliable knowledge from testimony or authority. (2) One or more premises are a priori false. (3) Several premises, taken together, produce a contradiction, so that the premises are explicitly or implicitly inconsistent. (4) One or more premises are vague or ambiguous to such an extent that it is not possible to determine what sort of evidence would establish them as acceptable or unacceptable. (5) One or more premises would not be rationally acceptable to any person who did not already accept the conclusions. In this case, the argument begs the question or is circular. Chapter 5 Internet sources: When accessing the internet for information you should keep the following three questions in mind. (1) (2) (3) What questions are you asking and what is relevant to your search Which sources are credible and which are not How to evaluate content and synthesize so as to construct your own argument It is important to understand the kind of internet pages you might encounter: New pages, informational pages, advocacy pages, business pages, entertainment pages, and personal web pages all require. Chapter 5 The credibility of the source is important. Asking these questions is important. (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) Who wrote the material? What are the qualifications of the person? With what institution or group, if any, is the person affiliated? If there is an institution or group, what is its nature or credibility? Is there information that would enable you to contact this author and make inquiries about the material? (6) Does this person give sources for his or her claims? Chapter 5 Dating of Material: Here are some problems with data from the internet: (1) Overabundance (2) Absence of gatekeepers (3) Mixing contexts (4) Instability (5) Confusing mixtures Chapter 5 Terms to review: A priori statement A posterior statement Authority Begging the question Common knowledge Empirical Faulty appeal to authority Inconsistency Provisional acceptance of conclusion Provisional acceptance of premises Refuted Testimony