Scientific Ethics

advertisement

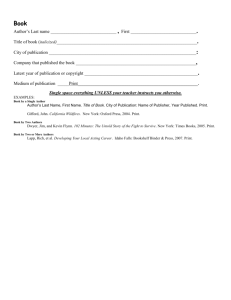

I. Scientific Ethics—an Introduction A. Source Documents 1. 2. B. Science is a Social Activity 1. 2. 3. 4. C. “On Being a Scientist”—National Academy of Sciences, 1995 “The Chemist’s Code”—American Chemical Society, 1994 Draw from past scientists; contribute to future work Students, technicians, postdocs, PI’s all work together Can have significant impact on society Can result in significant reward from society Science is frustrating 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Failed experiments Failed hypotheses Disagreements with colleagues and competitors Competition for money and recognition Dependence on other people for your success D. Flawed Human Process must become Enduring Truth 1. Creativity is countered with skepticism 2. New ideas are questioned and empirically tested 3. Must be able to convince others of your view of “how it works” E. Science and Ethics 1. Interplay of these forces result in hard decisions for scientists a. b. c. d. How do I treat this anomalous data? How do my values influence my research? Who should share credit for this work? Is that an honest error? Negligence? Misconduct? 2. Epistemology = study of the nature, origin, scope, of knowledge a. What is knowledge b. How is knowledge acquired c. What do people know 3. Society and Science a. Non-scientist play an increasing role in assessing science b. More social importance = more accountability to society II. Social Foundations of Science A. The complexity of science 1. 2. B. No single scientific method Not separate from technology, society, and personality Individual knowledge versus knowledge 1. 2. 3. Science is almost always collaborative Large advances are almost always individual Transfer from individual to society a. b. c. d. 4. C. Informal talking with colleagues Formal collaborations Oral presentations at meetings Written papers in journals Constant review and revision results from these interactions Results of this mechanism 1. 2. 3. Validation of scientific advances Generate accepted procedures and techniques Guard against deliberate or accidental errors III. Experimental Techniques and Data Treatment A. Generally Accepted Methods 1. 2. 3. Make data independently verifiable Eliminate bias Examples a. b. 4. Cold-fusion a. b. c. 5. Statistical tests of significance Double-blind studies Claims of energy from fusion at room temperature Implausible results from what is known of fusion; need extra proof Techniques didn’t eliminate errors; couldn’t be replicated “Frontier” research is inherently hard to prove a. b. c. d. Methods must be very clear and reproducible New methods need to be developed and verified New methods and new knowledge develop together Methods can be fallible i. Van Maanen’s methods on spiral nebulae showed in galaxy ii. Hubble used new, larger telescope showed not iii. Not an ethical problem, just a limitation of the method available IV. Values in Science A. Individual values greatly effect their science 1. 2. Curiosity, intuition, creativity are all key to scientific discovery Judgment in how to use those characteristics influence: a. b. c. d. B. Competing Hypotheses 1. 2. Several different explanations might work How do you choose which one to pursue a. b. c. C. Which problem to pursue—Interpretation of data What conclusions to draw Whom to work with and how How and when to discuss or disclose findings Must be internally consistent Should lead to accurate experimental predictions Unify disparate observations (especially if experimentation is difficult) Examples 1. 2. 3. Einstein and Q. Mech: “God does not play dice” with the universe. Lyell and Incremental Geology: Eternal God favors uniform history Eugenics: inferiority of races, rejection of Mendelian genetics D. Should we take value out of Science? 1. 2. 3. E. Tempering the effect of values on science 1. 2. 3. V. Desire to do good is a value and a scientific principle Honesty and objectivity are good (and good for science) Universe is understandable is a value (and good for science) The requirement of experimentation: If a hypothesis doesn’t stand up to experiment, it is rejected The social mechanism: others must understand, test, and accept an idea before it becomes part of scientific knowledge Self-examination: understand and deal with your own values Conflicts of Interest A. Multiple values may compromise scientific judgement 1. 2. B. Financial interest in a company might influence data interpretation Referee a paper that scoops your work Most institutions have “conflict-of-interest” policies to follow 1. 2. Disclosure of the conflict Outside monitoring of research or not doing the research at all VI. Publication A. The balancing act 1. 2. B. Accuracy of the data Priority and credit for the author(s) The Peer-Review System 1. 2. Henry Oldenburg, Royal Society of London Steps a. b. c. d. e. f. C. Prior to publication 1. 2. 3. D. Paper is submitted to an editor Paper is assigned to experts in the field to review for accuracy If “Peers” consent, the paper is published Publication established priority for the discovery Citation of others ideas until they become “common knowledge” Publication priority over discovery--only after published is it useful Research is “intellectual property”—some share, some don’t Patenting must take place prior to publication Should have the right to confirm accuracy and interpritation Post-publication: obligation to share data; even samples E. Non-Peer Reviewed Publication 1. 2. 3. 4. Posters, abstracts, invited talks, meeting presentations, internet Speeds and improves communication Propagates errors, weakens confidence News releases a. By-passes peer review, directly to the public b. Errors may not be caught c. Weakens public confidence if not significant, or in error F. Patents 1. Government grants temporary exclusivity, if results made public a. Makes useful technology available to the public b. Protects industry from others making money from their investment 2. Industry sponsored research may be held up from publication 3. Universities and other Institutions now have publishing policies G. Classified or Otherwise Sensitive Research 1. Scientist may need to get validation other than by publication a. Unclassified summaries b. Visiting committees 2. Should the research be done at all if dangerous to disclose (virus) H. Ethical problems related to publication 1. Performing substandard work to rush lots of publication a. Higher quality publications are more valuable than many publications b. “More people can count than can read.” James McCormick c. Universities beginning to limit number pubs considered for tenure 2. Publishing the same data in two journals a. Usually not the exact same data, but should have been one paper b. Clearly wrong, and done to increase number of publications 3. Always publishing short papers with little detail, not full papers a. Least publishable unit = minimum data to get published b. Many more “communications” than full papers is suspect 4. Other considerations a. b. c. d. Will someone scoop me if I hold on for a full paper? These students and postdocs need publications now My funding agencies want to see publication before they renew I’m giving up on this project, but I’ve got enough to publish something a. Publish as a “Note” rather than a communication b. Make data available in other ways VII. Allocating Credit A. Citation of other’s work 1. Purposes a. b. c. 2. Failure to cite others (or to cite them correctly) a. b. c. B. Acknowledge previous or related work done by others i. Conflicting data or hypotheses ii. Supporting data or hypotheses iii. Additional work in the same area Direct reader to related information Place your paper in context with the current state of the field Hard feelings; calls for corrections Hurting others careers: citations = reward for work, grants, promotion May be excluded from interaction with peers—reputation is hurt Authorship and Acknowledgement 1. How may authors? a. b. c. d. Historically, often just one Current collaborative nature of science means single author rare now Field dependent: Chemistry: 5-10 is common High Energy Physics or Genome Sequencing: hundreds 2. Who’s the most important author? a. b. c. 3. Avoiding problems a. b. c. 4. In some fields, the order listed is the order of contribution In Chemistry, it’s often this way, with PI listed last Some journals only list authors alphabetically Know going into a collaboration how authorship will be done Include anyone who has contributed—intellectually, or physically i. Instrument technicians (often Ph.D.’s) are often acknowledged ii. Colleagues who only discussed the idea are acknowledged iii. X-ray crystallographers seem always to be authors Avoid “honorary” authorship Responsibility of authors a. b. Each author is accountable for the results Each author should sign off on the results and agree with conclusions VIII. Error and Negligence A. Results are always provisional 1. 2. B. New data or new methods can change your interpritations All physical measurements are subject to error Types of errors 1. 2. Random errors can’t be accounted for or corrected Systematic errors can be discovered and accounted for a. b. c. 3. Instrumental, environmental errors Human errors—honest mistakes If discovered after publication, publish a correction—won’t be condemned Negligence = haste, carelessness, inattention a. b. Doesn’t meet the standards of professional scientists Reputation will suffer; public confidence is lowered IX. Scientific Misconduct A. Deception 1. 2. 3. B. Making up data or results Changing or falsifying data or results Using someone else’s ideas as yours = plagiarism Consequences 1. Minor ethical lapses a. b. 2. Scientific misconduct a. b. c. d. e. C. Can harm other people (medical research) Wastes tax dollars Damages the reputation and values of science to society; funding Destroys personal reputation, livelihood, research career Can be punished by the legal system (in rare cases) Procedure 1. 2. D. Handled within the scientific community Peer review, administrative action, tenure review Preliminary Investigation, usually be responsible institution Adjudication: Due Process to accused Other: fraud, harassment, tampering—normal legal system X. Responding to Ethical Violations 1. You have an obligation to act a. b. c. 2. What to do a. b. c. d. 3. Easiest to do nothing Power differential makes it difficult to act Accusations are very powerful—be certain of the violation Discuss it with friend, advisor, chair, etc… to get advice If you proceed, verbal complaints can often be dealt with easier Written complaints will seriously effect careers Institutions usually have a system in place, but rarely used Contacts a. b. National Science Foundation (NSF): Office of Inspector General National Institutes of Health (NIH): Office of Research Integrity XI. The Chemists Code of Conduct A. American Chemical Society: www.chemistry.org B. Responsibilities to: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. The Public—serve the public interest The Science of Chemistry—thorough, accurate, advancement The Profession—ethical considerations The Employer—honest effort for employer’s interests Employees—fairness, respect, safety, credit Students—obligation to society, treat with respect Associates—credit, respect, encouragement Clients—faithful, confidentially, honestly, charge fairly The Environment—understand consequences, protect