Endometrial carcinoma

advertisement

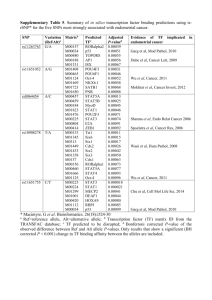

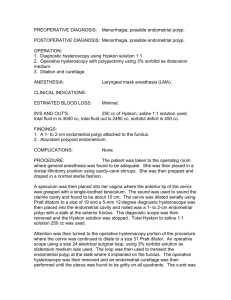

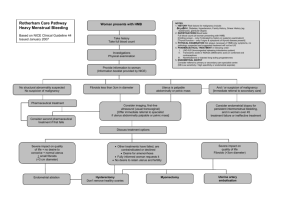

Endometrial carcinoma Dr. B. Zuckerman SZMC 2014 Endometrial Carcinoma in US (2011) • • • • • • • The most common gynecological malignancy 46,470 new cases 8,120 deaths Median age of diagnosis: 61 (most – 50-60 ) 90% - over the age 50 20% - before menopause 5% - before age 40 Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, Jemal A. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:212-36 Endometrial Carcinoma • 90% experiencing abnormal uterine bleeding • 75% - early stage disease • Stage 1 – 72% Stage 2 – 12% Stage 3 – 13% Stage 4 – 3% Stage St 1 St 2 St 3 St 4 Endometrial Carcinoma • Early onset of symptoms • Well-established diagnostic guidelines • Overall – good prognosis • High-risk or advanced disease – poor prognosis and death Malignancies of uterine body: Classification • Epithelial – 90% Endometrioid, serous, clear cell, mucinous • Mesenchymal – 5% Endometrial stromal sarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, other sarcomas • Mixed – 3% Carcinosarcoma, adenosarcoma • Secondary – 2% Uterine malignancies Carcinoma of endometrium Types of endometrial carcinoma Epidemiological risk factors • Chronic estrogenic stimulation • Associated medical illness • Demographic characteristics Chronic estrogenic stimulation Factors Relative risk Estrogen replacement (no progestin) 2-12 Early menarche / Late menopause 1.6-4.0 Nulliparity 2-3 Anovulation ND Estrogen-producing tumors ND Associated medical illness Factors Relative risk Diabetes mellitus 3 Obesity 2-4 Hypertension 1.5 Gallbladder disease 3.7 Prior pelvic radiotherapy 8 Demographic characteristics Factors Relative risk Increasing age 4-8 White race 2 High socioeconomic status 1.3 European/North American country 2-3 Family history of endometrial cancer 2 Precursors of endometrial carcinoma Simple hyperplasia Increased number of glands but regular glandular architecture Precursors of endometrial carcinoma Complex hyperplasia without atypia Crowded irregular glands. Cytological atypia is absent Precursors of endometrial carcinoma Simple atypical hyperplasia Simple hyperplasia with presence of cytological atypia (prominent nucleoli and nuclear pleomorphism) Precursors of endometrial carcinoma Complex atypical hyperplasia The endometrial glands are irregular in size and shape with branching and outpouchings (complex hyperplasia) with cytological atypia Precursors of endometrial carcinoma Foci of well-differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma Areas of complex atypical hyperplasia Precursors of endometrial carcinoma Malpica, Deavers, and Euscher. Biopsy interpretation of the uterine cervix and corpus. Lippincott, William & Wilkins, p. 167-168, 2010 Hereditary Syndromes • Endometrial cancer is not typically a hereditary disorder • Genetic predisposition is seen in up to 10% of patients (5% women with Lynch syndrome) Lynch syndrome • Hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) • Autosomal dominant inherited cancer susceptibility syndrome Lynch syndrome • Germ line mutation in one of the DNA mismatch repair genes (MSH2, MLH1, MSH6, PMS2) • Early age at cancer diagnosis and the development of multiple cancer types, particularly colon and endometrial cancers • 40% to 60% risk of endometrial cancer Cellular classification Endometrioid type 80% • • • • G1 Well differentiated G2 Moderately differentiated G3 Poorly differentiated Other Non-endometrioid type (G3) 20% • • • • • • Papillary serous <10% Clear cell 4% Mucinous 1% Squamous cell <1% Mixed 10% Undifferentiated Natural history Primary sign: abnormal bleeding Natural history Myometrial invasion Natural history Lymph vascular invasion Natural history Lymph none metastases Staging Surgical Stage 1 IA: No or < ½ myometrial invasion IB: Invasion >= ½ of the myometrium Stage 2 II: Invasion of cervical stroma, but does not extend beyond the uterus. Stage 3 IIIC: Cancer has spread to lymph nodes in the pelvis - IIIC1 and/or around the aorta - IIIC2 IIIA: Cancer has spread to the outer layer of the uterus and/or to the fallopian tubes, ovaries, or ligaments of the uterus IIIB: Cancer has spread to the vagina and/or to the parametrium Stage 4 IVA: Cancer has spread into the bladder and/or bowel IVB: Cancer has spread beyond the pelvis to other parts of the body Diagnosis: endometrial biopsy • Abnormal uterine bleeding (older than 40) • Atypical glandular cells in PAP (older than 35) Ultrasound 96% of bleeding postmenopausal women with cancer have endometrial thickness greater than 5 mm US triage patients with PMB Hysteroscopy Indication: symptoms of AUB continue and cannot by explained by the office biopsy Preoperative evaluation Type I tumors • Physical examination • Chest radiograph • Electrocardiogram Type II tumors • CT or MRI (CT scan imaging changed treatment in 11%) • Serum CA 125 (may be a predictor of extrauterine disease) Comprehensive surgical staging • Hysterectomy • Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy • Pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy Surgical staging controversy Proponents • Full staging should be performed on all patients regardless of tumor grade or depth of invasion Opponents • No staging in clinical early stage disease: low likelihood of lymph node metastases and the risks of a lymphadenectomy outweigh the potential benefits of having the information gained from staging A third group: surgical staging is indicated in a select group of women at highest risk for extrauterine disease; however, the precise definition of a high-risk patient remains elusive Surgical staging controversy: RCT Italian trial • 514 patients, 31 centers in two countries, 10-year period • Both early and late postoperative complications occurred more frequently in patients who had undergone a pelvic lymphadenectomy • The 5-year disease-free and overall survival rates were similar between the two groups (81% and 86%) Systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy vs. no lymphadenectomy in early-stage endometrial carcinoma: randomized clinical trial. Panici PB, Stefano S, Maneschi F, et al. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:1707. Surgical staging controversy: RCT ASTEC (A Study in the Treatment of Endometrial Cancer) • Objective: to determine if lymphadenectomy increases survival independent of adjuvant irradiation • 1,408 women, 85 centres, 4 countries, over 7 years Efficacy of systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (MRC ASTEC trial): a randomized study. The writing committee on behalf of the ASTEC study group. Lancet 2009;373:125. ASTEC (A Study in the Treatment of Endometrial Cancer) • 1st randomization: standard surgery vs. standard surgery plus lymphadenectomy • 2nd randomization in intermediate and high-risk group (IA or IB with high-grade pathology, or IIA): radiation vs. no further therapy • no evidence of a benefit in terms of overall survival or recurrence-free survival for pelvic lymphadenectomy in women with early endometrial cancer Surgical staging controversy Retrospective data • The outcomes of 27,063 women with unstaged endometrioid uterine cancer. • From Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database • 39,396 patients • Surgical staging procedures that included a lymphadenectomy vs. no lymphadenectomy Chan JK, Wu H, Cheung MK, et al. Gynecol Oncol 2007;106:282. Retrospective data • In stage I grade 3 patients, those who underwent lymphadenectomy had a better 5-year disease-specific survival than those without lymphadenectomy • no benefit for lymphadenectomy was seen for patients with stage I grade 1 and grade 2 Surgical staging controversy Additional studies are needed to determine the role of lymphadenectomy, the extent of lymphadenectomy, and the indications for surgical staging in patients with endometrial cancer Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy • Alternative to complete pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomies • Endometrial cancer tumors: difficult to visualize and to inject Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy • In a prospective multicentre study (SENTI-ENDO) of sentinel lymph node biopsy via cervical injection, pelvic sentinel lymph nodes (SLNs) were detected in 89% of patients; and the sensitivity and negative predictive value of SLN biopsy were 84% and 97%, respectively. Ballester M, Dubernard G, Lécuru F, et al. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:469-76 Surgical Approaches • Surgery represents the cornerstone for treatment of endometrial cancer • Standard approach: exploratory laparotomy, hysterectomy and bilateral salpingooophorectomy • Comorbidity: severe obesity, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases Surgical Approaches • Minimizing surgical morbidity: minimally invasive surgery (Laparoscopic surgery, robotic-assisted surgery ) • Less blood loss, decreased transfusion rates, shorter length of hospitalization, and a faster return to daily activities GOG trial: laparotomy vs. laparoscopy • Laparoscopic surgical staging for uterine cancer is feasible and safe in terms of short-term outcomes (2010) • Fewer complications and shorter hospital stays • Potential for a small increased risk of cancer recurrence with laparoscopy versus laparotomy • 5-year overall survival being almost identical in both arms at 89.8% (2012) Walker JL, Piedmonte MR, Spirtos NM, et al. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:695-700 Robotics Robotics • In 2005 the U.S. FDA approved the daVinci robotic system for gynecologic procedures • The advantages of the robotic system over standard laparoscopy: high-definition three-dimensional vision, more surgical precision and dexterity, improved ergonomics for the surgeon, improved teaching capabilities for trainees • The disadvantage: very high cost Robotics To date, there are no prospective trials comparing laparotomy vs. laparoscopy vs. robotic surgery in the management of patients with endometrial cancer Uterine risk factors Major prognostic factors • Grade or cell type • Depth of myometrial invasion • Tumor extension to the cervix Less important • Extent of uterine cavity involvement • Lymph–vascular space invasion • Tumor vascularity Extrauterine risk factors • • • • • Adnexal metastases Pelvic or para-aortic lymph node spread Peritoneal implant metastases Distant organ metastases Positive peritoneal cytology Radiation Therapy • Today it is delivered almost exclusively following surgery in women with adverse pathologic features • External beam approach is whole pelvic radiotherapy • Brachytherapy Adjuvant Radiation Therapy • Reduces the risk of pelvic recurrence in early stage patients with adverse pathologic features • Does not improve survival Adjuvant external beam radiotherapy in the treatment of endometrial cancer (MRC ASTEC and NCIC CTG EN.5 randomized trials): pooled trial results, systematic review and meta-analysis. ASTEC/EN.5 Study Group, Blake P, Swart AM, et al. Lancet 2009;373:137 Adjuvant brachytherapy alone • Brachytherapy vs. pelvic radiotherapy: no differences in overall or disease-free survival • Less toxicity Vaginal brachytherapy versus pelvic external beam radiotherapy for patients with endometrial cancer of high-intermediate risk (PORTEC-2): an open-label, non-inferiority randomised trial. Nout RA, Smit VT, Putter H, et al. Lancet 2010;375:816 Quality of life after pelvic radiotherapy or vaginal brachytherapy for endometrial cancer: first results of the randomized PORTEC-2 trial. Nout RA, Putter H, Jurgenliemk-Schulz IM, et al. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3547 Adjuvant chemotherapy in early stage disease • Pelvic radiotherapy versus chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and cisplatin [CAP]) • No differences in progression-free or overall survivals were seen at 5 years Randomized phase III trial of pelvic radiotherapy versus cisplatin-based combined chemotherapy in patients with intermediate and high-risk endometrial cancer: a Japanese Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Susumu N, Sagae S, Udagawa Y, et al. Gynecol Oncol 2008;108:226 Hormone (Progesterone) Therapy • Complex atypical hyperplasia and low-grade endometrial cancers diagnosed in young women who are still considering child-bearing • Very high risk surgery group