Julia Wohlfarth Doctor Wooster History 1301

advertisement

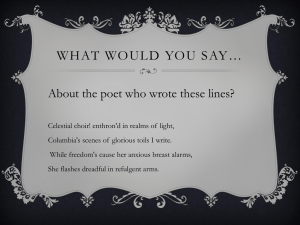

Julia Wohlfarth Doctor Wooster History 1301-246 2 November 2015 Beating the Odds “It was not natural. And she was the first” (Jordan 254). Although Phillis Wheatley is not generally considered as someone who stood up to slavery, by taking a closer look at her poetry it is evident that she did write with underlying tones of abolition and equality. By analyzing Wheatley’s poems On Being Brought from Africa to America and To the Right Honourable William, Earl of Dartmouth, it can be discovered that not only did she write about slavery, but she also wrote against it. Phillis Wheatley was many things: a writer, a poet, educated, a woman, literate, and above all— a slave. In his biography of Phillis Wheatley, author Vincent Carretta explains that at a very young age she was “…kidnapped from her family in Africa and forced to spend up to two months crossing the Atlantic” (1). However, Phillis Wheatley did not let slavery define her. After being bought by John and Susanna Wheatley, Phillis Wheatley was taught to read and write by Susanna and her children, something quite uncommon of slaves at the time (Carretta 13-22). Merely “sixteen months after her entry into the Wheatley household Phillis was talking the language of her owners” (Jordan 254). It didn’t take long for her to use these skills to begin writing what she is still famous for: poetry. The National Women’s History Museum states that she wrote and published her first poem at the young age of fourteen, and only three years later was able to publish a book of her poetry titled Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. The publication of her book made Phillis Wheatley the second woman to be published in America, and the first African American, as June Jordan put it: “It was not natural. And she was the first” (252). In the span of her life Phillis Wheatley was able to accomplish much more than would be expected of a woman living in slavery during the eighteenth century. In fact, her publisher thought that many people would not believe that Wheatley had actually written her poems, so he requested distinguished men like John Hancock and Charles Chauncey to swear that she had written them herself (Flanzbaum 71). Not only did she manage to learn how to read and write in English as well as Greek and Latin (National Women’s History Museum), but she became a published poet who was admired by Voltaire (Seeber 260) and George Washington (Washington). In his article on Phillis Wheatley, Edward Seeber writes of the huge significance of Phillis Wheatley during her life, stating that Voltaire, who generally did not think very highly of African Americans “… was one of the first eminent writers to praise Phillis Wheatley” (260). Not only was Phillis Wheatley praised by Voltaire, but also George Washington who wrote a letter to her, praising her “great poetical talents,” as well as calling her a “genius” and “favoured by the Muses,” even inviting her to come visit him if she ever found herself in town (Washington). With the help of her owners it didn’t take long for Phillis Wheatley to become quite popular during the eighteenth century. This popularity is even more astounding considering her social standing as a slave. Two of the most significant poems written by Phillis Wheatley are On Being Brought from Africa to America and To the Right Honourable William, Earl of Dartmouth. In his article, Personal Elements in the Poetry of Phillis Wheatley, Arthur Davis first discusses the major criticisms of Wheatley’s poetry, writing that “the most frequently stated criticism of Phillis Wheatley is that she was too highly objective in her writing…” (191). He goes on to state that “…she is not as devoid of racial and personal feeling…” as critics have claimed her to be, and that by re-examining her poetry it can be discovered “…that Phillis Wheatley does speak of her own problems more often than is commonly recognized” (Davis 192). Davis continues by analyzing Wheatley’s poem, On Being Brought from Africa to America, observing that her use of the phrase “scornful eye” was likely a feeling she knew all too well. In addition, June Jordan also analyzed Wheatley’s poem, commenting on the line “once I redemption neither sought nor knew,” stating that by this Wheatley meant that she once lived without the terms, but since she was forced to consider these terms of “good and evil/redemption and damnation” that she is “black as Cain,” but still able to be an angel, regardless of the color of her skin (255). These subtle implications made by Wheatley prove that while on the surface her poetry comes off as objective, it is actually more personal when looked at more closely. Furthermore, Wheatley’s poem To the Right Honourable William, Earl of Dartmouth more openly criticizes the institution of slavery in America. Davis continues his analysis of Wheatley’s poetry with an analysis of this poem, stating that “…the personal reference…” to freedom “…makes it as strong a protest against slavery as a slave could utter…” (195). Additionally, the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History references the lines in the poem “Wonder from whence my love of Freedom sprung” and “I, young in life, by seeming cruel fate Was snatch’d from Afric’s fancy’d happy seat: What pangs excruciating must molest, What sorrows labour in my parent’s breast?” stating that in these lines she is proclaiming that the reason she loves freedom is because of being a slave. She then goes on to give details about her kidnapping from Africa and her parents. Lastly, she writes “and can I then but pray others may never feel tyrannic sway?” With this, she perhaps makes her boldest accusations against slavery, by making a comparison between the way England treated the colonies and the way slave owners treat their slaves. This accusation would have been incredibly apt at the time due to very strenuous ties between America and England. Phillis Wheatley is still extremely relevant and important today for multiple reasons. Phillis Wheatley is rarely discussed in history even though she is one of the most significant historical figures of this time period. Wheatley was the first African American, and second woman published in America all while being a slave. She is one of the founders of African American literature in America. As Carretta wrote, “The little girl who had been enslaved in Africa…” became “…the founding mother of African American literature” (1). She deserves more historical credit, because she is often overlooked in history, due to the fact that American history is often taught from the white male perspective. As reported by Aljazeera, administrators of the school districts in and around Denver, Colorado attempted to change the U.S. history curriculum to only “present positive aspects of the nation and its heritage.” Furthermore, writer Daniel Czitrom writes for CNN that too often American history “ignores or marginalizes African-Americans, women, Latinos, immigrants and popular culture.” Even more shockingly, Trymaine Lee from the Huffington Post reports that “a group of Tea Party activists in Tennessee… is seeking to remove references to slavery and mentions of the country’s founders being slave owners.” These attempts to change what is taught in American history are simply gross misrepresentations of the past, but that doesn’t make them harmless. It is completely historically inaccurate to leave out the fact that the founding fathers owned slaves. It is a part of America’s history, for better or for worse. It is for reasons such as these that it is incredibly important to remember the past and learn about the lives of many African American’s this country is built on. Phillis Wheatley is often overlooked when discussing those who spoke out against slavery, however through an in depth analysis of her poetry, specifically On Being Brought from Africa to America and To the Right Honourable William, Earl of Dartmouth it is evident that she should be given much more credit. Works Cited Carretta, Vincent. Phillis Wheatley: Biography of a Genius in Bondage. Athens, GA: U of Georgia, 2011. Print. Czitrom, Daniel. "Texas School Board Whitewashes History." CNN. Cable News Network, 22 Mar. 2010. Web. 16 Oct. 2015. Davis, Arthur P. "Personal Elements in the Poetry of Phillis Wheatley."Phylon (1940-1956) 14.2 (1953): 191-98. JSTOR. Web. 17 Oct. 2015. “Denver Students Stage Walkout over Whitewashing History.” Al Jazeera America. Al Jazeera and The Associated Press, 24 Sept. 2014. Web. 01 Nov. 2015. Flanzbaum, Hilene. "Unprecedented Liberties: Re-Reading Phillis Wheatley." MELUS 18.3, Poetry and Poetics (1993): 71-81. JSTOR. Web. 16 Oct. 2015. Jordan, June. "The Difficult Miracle of Black Poetry in America or Something like a Sonnet for Phillis Wheatley." The Massachusetts Review 27.2 (1986): 252-62. JSTOR [JSTOR]. Web. 11 Oct. 2015. Lee, Trymaine. “Tea Party Group Pushes for Sunnier Side of Slavery in Textbooks.” The Huffington Post. The Huffington Post, 23 Jan. 2012. Web. 01 Nov. 2015. "Phillis Wheatley." National Women's History Museum. National Women's History Museum, n.d. Web. 17 Oct. 2015. Seeber, Edward D. "Phillis Wheatley." The Journal of Negro History 24.3 (1939): 25962. JSTOR. Web. 10 Oct. 2015. Washington, George. “George Washington to Phillis Wheatley.” 28 Feb. 1776. The Library of Congress. Wheatley, Phillis. “On Being Brought from Africa to America.” circa. 1773. Internet Archive. 16 Oct. 2015 Wheatley, Phillis. “To the Right Honourable William, Earl of Dartmouth” circa. 1773. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. 16 Oct. 2015