From Wine to Beer:

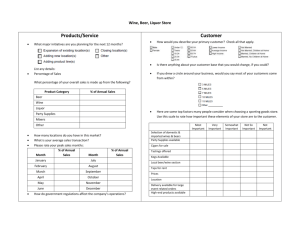

advertisement

From Wine to Beer: Changing Patterns of Alcoholic Consumption and Living Standards in Late-Medieval Flanders, 1300 – 1550 by John Munro (Toronto) From Wine to Beer in LateMedieval Flanders: Introduction • 1) Northern Europe: land of beer & butter; vs. southern Europe as land of wine and olive oil: not always so • 2) Meagre evidence on this shift: declining per capita wine consumption and rising per capita beer consumption: from studies by: Margery James, Michael Postan, Hans Van Werveke, Jan Craeybeckx, Herman Van der Wee, Richard Unger • 3) The Postan Thesis (CEH: 1952): technological: • - the crucial factor was the introduction of hops: in North German (Hamburg) and Dutch towns, from the 1320s • ‘hop’ thesis basically endorsed by Craeybeckx, Van der Wee, Unger (and many others): how valid is the thesis? • 4) Evidence on continued importance of wine: Antwerp Brewing with hops • 1) The importance of hops: replacing gruit • a) Long Distance Trade: hops improved both the stability and durability of brewed beers (as well as taste): stored for longer times, transported over longer distances • b) Safety in ‘drinkability’: hops improved the sterilization process (not all bacteria killed by boiling: note that beer is 90% water) • 2) Wine and Beer: in pre-modern societies, were not ‘sinful luxuries’ but vital necessities: because water and milk were generally unsafe to drink, especially in urban areas (pollution) • - Koch (1876), Pasteur (1878): discovery of bacterial transmission of diseases sewage & water purification systems in NW Europe, North America rapid fall in mortalities • 3) Nutritional Values of Beer (over wine): Nutritional Values of Beer • 1) Robert Allen’s consumer price index: • - Beer: 20.6% share: in his basket of consumer expenditures (same for wine in southern Europe) • cf: Phelps Brown & Hopkins (England): 22.5% share; Rappaport (London): 20.0%; Munro (Flanders): 20.43%; Van der Wee (Brabant): 17.08% (vs. 1% for wine) • 2) Allen’s caloric quantification: for annual household budgets: in late-medieval, early-modern Europe • a) northern budget: 182 litres of beer = 77,532 C. • b) Mediterranean budget: 68.5 litres wine = 58,035 C. Problems with the Hop Thesis: the Flemish Urban Evidence • 1) Basic problem with the ‘hop thesis’: major shift from wine to beer comes too late: not till 1430s • 2) The Evidence the Treasurers’ accounts for Bruges and Aalst: annual sales of excise-tax farms on wine, beer, other foodstuffs (esp. grains, fish), textiles • 3) excise tax-farms (on urban household consumption): urban revenues chiefly used to finance public debt payments: on rentes (annuities) sold primarily to finance warfare (European-wide). • 4) Wine and Beer: principal taxes: on necessities that were also very addictive highly inelastic demand • - very highly regressive taxes on all urban households The Bruges Financial Accounts • 1) Especially valuable: in two respects: • a) only urban accounts extant from early 14th century: from 1308, with few annual lacunae (unlike Ghent accounts; or Ypres – none extant until 1406): data in graphs and tables in this study to 1500 • b) evidence on consumption of foreign as well as domestic beers. • 2) Foreign beer imports: • a) Hamburg beers: from 1333 (possibly hop beers) • b) ‘Hop & Delft’ beers: from 1380: Dutch beers: initially much more important than Hamburg beers, but sharply diminishing from 1411: • - 1430: Delft beers amalgamated with German beers • c) from 1430s: foreign beers decline in both absolute (‘real) & relative importance predominance of Bruges beer • d) Why? Warfare with Hanseatic League and England – to 1470. Aalst vs. Bruges Financial Accounts • • • • • • • • • • 1) Importance of the Aalst annual financial accounts: - a) begin in 1395: but then virtually continuous (to 1550) - b) provide wage data to 1550; Bruges: none from 1480 2) Comparisons with the Bruges accounts on beer: a) Aalst: primacy of beer established from the beginning: 63% of total alcoholic excise farms in 1390s, but still only 67% ca. 1420 b) Bruges: beer: 34% of that total in 1308-10; only 33% in 1381-85; 37% in 1416-20 - note: Bruges wealthier, more mercantile, cosmopolitan town greater retained preference for imported wines. c) In both sets: more decisive shift to beer from 1430 - i) Bruges: 52% in 1431-35: almost continuous rise to 70% in 1490s - ii) Aalst: 73% in 1431-35 to 83% in 1466-70; 80% in 1496-1500 Estimating the Burdens of Urban Excise Taxes (1) • 1) Problem: the nominal money-of-account values of the excise-tax farms sales are otherwise useless in estimating tax burdens • 2) Reason: the impact of coinage debasements (finance warfare) consequent inflations • - grams silver in Flemish penny (groot): fell from 2.067 g in 1350 to 0.463 g in 1482 (0.479 in 1500) • - Flemish CPI (1451-75=100): from 60.5 in 1351-56 to 184.5 in 1486-90: 3-fold inflationary rise • 3) Note: periodic coinage debasements sharply reduced real incomes of wage-earners & those on fixed incomes (salaries, rents, pensions, etc.): RWI = NWI/CPI • - BUT so did the rises in highly regressive excise taxes Estimating the Burdens of Urban Excise Taxes (2) • 4) Two statistical methods of estimating the ‘real’ burden of urban excise tax farms: • a) Calculate the number of Flemish ‘commodity baskets’ (in the CPI) whose value = total revenues of the excise tax farms • (Bruges: alcohol only; Aalst: all excise farms) • b) Calculate the number of years’ of a master mason’s money-wage income whose value = total revenues of the excise tax farms (Aalst only: and for all excise tax farms) Real Tax Burdens during the Golden Age of the Artisans • 1) 15th-century ‘Golden Age of the Artisans’ (and labourers): concept based on evidence for real-wages of craftsmen in Flanders (and Brabant, and England): • 2) Rise in real wage index (RWI = NWI/CPI) from ca. 1440 to ca. 1470: basically determined by deflation: when coinage debasements had ceased and other forces for monetary contraction fall in price level Importance of the Aalst wage and excise-tax data • 1) The real wage data for Aalst during the Golden Age: also show marked rise c. 1440 – c. 1470 (RWI = NW/CPI) • 2) BUT the real value or burden of the excise tax farms, as measured in annual incomes of master mason: also rise in the very same period, offsetting rise in crude real wages • 3) Rising urban excise tax burden: rising taxes to finance steep rise in public debts incurred to finance previous and current warfare • - note England: no such excise taxes until 1640s (Civil War) • 4) Importance of the era from 1430s for Flanders: • a) rising excise-tax burdens: from warfare, which had also spawned deleterious coinage debasements • b) more rapid decline in traditional woollen draperies • c) also period of more rapid shift from wine to beer • - was that more pronounced shift due to real income changes? Demographic Questions • 1) Estimates of burdens of the urban excise taxes: based on assumptions of stable populations • 2) But, did Flemish populations (urban & rural) continued to decline, as in England? Evidence for Flanders is mixed: from 7% to 28% (Ypres); but some towns did not decline. • 3) Significance of the question: if urban populations fell Δ per capita tax burden: i.e., increase in household taxes • 4) For duchy of Brabant – just to east of Aalst, evidence of severe population decline, 1437 to 1496 – along with increased poverty, especially in small towns and villages • 5) Golden Age in mid 15th century?: for the artisan or for bacteria (Thrupp): but beer is always golden • except for those who prefer donker bier