File

advertisement

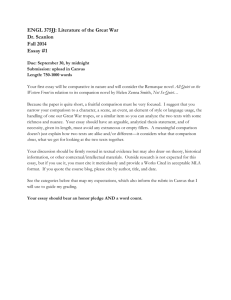

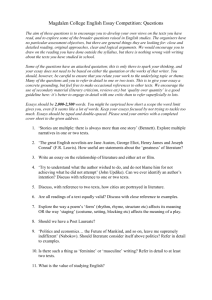

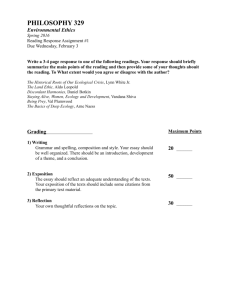

THE INTEGRATED EXTENDED RESPONSE THE HIVE Account - Account for: state reasons for, report on. Give an account of: narrate a series of events or transactions Analyse - Identify components and the relationship between them; draw out and relate implications Compare - Show how things are similar or different Contrast - Show how things are different or opposite Critically (analyse/evaluate) - Add a degree or level of accuracy depth, knowledge and understanding, logic, questioning, reflection and quality to (analyse/evaluate) Define - State meaning and identify essential qualities Demonstrate - Show by example Describe - Provide characteristics and features Discuss - Identify issues and provide points for and/or against Explain - Relate cause and effect; make the relationships between things evident; provide why and/or how Identify - Recognise and name Justify - Support an argument or conclusion Outline - Sketch in general terms; indicate the main features of Recommend - Provide reasons in favour Recount - Retell a series of events Summarise - Express, concisely, the relevant details Synthesise - Putting together various elements to make a whole This is the text type. Not all extended responses are formal essays. Extended responses cover a number of text types (modes/mediums/forms). Students are required to analyse, synthesise, manipulate and evaluate information and ideas to create their own texts for a specific purpose and audience. This may involve expressing and justifying a point of view, explaining and evaluating an issue, proposing a solution or solving a problem in the creation of texts. Expository texts explain, analyse or evaluate. An expository text describes objects, events or processes in an objective manner, presents or conveys an argument, states the solutions to a problem or explains a situation. The following are examples of expository texts: media analysis magazine article panel discussion seminar/speech/address argument/discussion/conversation analytical exposition (extended response) Persuasive texts argue or persuade, to convince readers to accept particular perspectives or points of view. The following are examples of persuasive texts: feature article profile or column review interview public address (Australia Day or similar) discussion forum letter to the editor Reflective texts ponder, muse or reflect on events and experiences. The following are examples of reflective texts: memoir personal narrative autobiography and biography obituary testimonial director’s notes personal letter/email Imaginative texts use language in aesthetic and engaging ways to entertain, to move, to express and reinforce cultural identity. The following are examples of imaginative texts: poems short story drama script television or film script monologue dramatic recreation news report diary/journal entry Your introduction is the first thing a marker reads. A good engaging introduction is a key element in all of your responses. Address the question – use language from the question (don’t just repeat it!) Outline your text title/s, composer/s and form/s. Take care to be correct! Establish a THESIS – this is your main argument; your answer/ position in response to the essay question. Your essay should act as a PLAN for your response. It should help the marker understand exactly what you’ll be discussing in your essay. Tip! Break down your question. Circle and underline key words and verbs. Then, consider alternative words (synonyms) for the key words to use throughout your essay. Be sure you address the key verbs (for example, analyse, discuss, evaluate, compare). You have studied two texts composed at different times. When comparing these texts and their contexts, how would the modern responder’s understanding of each text be developed and reshaped? Addresses the Q Text / Composer / Form Thesis Statement Fay Weldon’s epistolary commentary featured in ‘Letters to Alice on First Reading Jane Austen’ incites the modern responder to reconsider their initial understanding of the values presented in Jane Austen’s ‘Pride and Prejudice’. Fay Weldon provides a unique insight into the values representative of Austen's era to reshape their ‘boring, petty and irrelevant’ image, highlighting the need for a deeper appreciation of the 19th Century. Weldon’s tendentious approach successfully convinces the responder to find merit in her academic and feminist inspired reading of ‘Pride and Prejudice’. It is through her didactic critique that the responder's initial perception of Austen's world is transformed, allowing responders to gain a distinctly new perspective of the portrayal of marriage, the role of women and the importance of education. Elevated Vocab Three Key Concepts = Three Central Paragraphs Your thesis should answer the question - “If I had only one idea I wanted my reader to understand, what would it be?” WHAT? WHY? A concise, well-worded sentence that summarises your major point (your opinion) of the topic. It let’s your reader know what theory or ideas you are trying to prove. WHERE? If writing a single intro paragraph it should be the 1st or 2nd sentence. It needs to be the FOCUS of your introduction. You need to continue to refer to your thesis throughout your essay, however, try to change up some of the language. There are different levels of thesis statements. Take a look at the ones below, which all answer the question: How is hope important in The Book Thief? Simple and general: Hope is important in The Book Thief. More specific: Hope is important to some characters in The Book Thief because they need it to survive. Specific and well-written: World War II was a desperate time for both Germans and Jews. For many of the characters in Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief, hope was the only thing that gave them the willpower to try to survive with the hope of creating a better life. Specific, stylish, and with some foreshadowing: In the desperate times of World War II, hope was the only thing that gave many of the characters in The Book Thief the willpower to survive with the desire to create a better life, filled with justice and equality. Remember: one paragraph for each main point/argument! Start with your POINT—your topic sentence that explains your opinion about the paragraph’s topic. State your QUOTE/S or EVIDENCE as primary evidence to support your point, integrated into your own sentence. When you are referring specifically to techniques, use the IEEL scaffold (Identify-ExampleEffect-Links). Include an EXPLANATION of one or more sentences explaining how the quote supports your point. You can have more than one quote or piece of evidence, so repeat the Quote/Explanation steps as needed. Re-state your main position/thesis statement in which you address the question (use language from the question). But DON’T just repeat your introductory statement. For example: Original thesis: Violent movies exemplify and glorify what is wrong with our culture. Conclusion: The violence in society is reflected in the movies we view. Mention your texts, composers and forms. Finish on a strong statement that summarises your major ideas from the essay. Tip! Avoid saying “… in conclusion”. Your conclusion should be around 3-5 lines in length and should take around 3-5 minutes to write in exam conditions. Watch your time to ensure you write a conclusion. Quotations add evidence but must not be too long – the essence of the quotation should be selected and only this should be used in an examination essay. Focusing on the essential parts of a quotation allows you to develop your own explanation and illustrate understanding and personal engagement with the text. Use punctuation to paraphrase. “…it was a perfect day [in Riverdale]… [the sun was] a ball of red dust swirling in the lurid teal sky.” Placing a quotation first in a sentence changes the focus of the idea and implies that you are jumping from quotation to quotation. Make a statement about the topic first and then use the quotation to illustrate this. This foregrounds and then supports the idea. Use integrated quotes. Quotations should become part of the sentence as much as possible rather than inserted. Integrating your quotes is more sophisticated. The structure of your sentence should allow you to remove the quote marks and the sentence should make sense with the quote. For example: 'Mrs Bennet is a character that is thought to be silly and unwise as shown in the quote, "foolish and petty".' Not integrated 'Mrs Bennet is portrayed by Austen to be a "foolish and petty" character'. Integrated Underline key words and annotate your question to ensure that you address ALL aspects of a question. Then be sure to ADDRESS all aspects of the question. Only write in the first person if the question specifically asks you to write using a personal voice. Use your time wisely – a wasted few minutes could mean your work is half a page less than it could be! You should be writing at least one page every 10 minutes – and aiming to be writing one every 7-8 minutes by your HSC exams. Find ways to abbreviate long titles of texts. Practice hand writing within time constraints to ensure you are physically up to the task! Keep asking for feedback and re-working your practice responses until it is a high band piece of work. REMEMBER – if you have not completed high quality responses when you have time and resources on your side – how are you going to generate a solid response in exam conditions? Any answer MUST respond directly to the set question. Do not use language specific to past practice questions. It’s important to know when to leave out information if it isn’t relevant to the question. Knowing the texts is essential but only that knowledge which is relevant should be used and care has to be taken not to tell the story. A way of avoiding recount is by organising the essay under arguments or paragraphs that refer to ideas and concepts rather than following the novel or film from beginning to end. Understanding HOW the composer has made meaning is important but this information must SUPPORT any answer and not DRIVE it. The techniques must offer valid justification of how meaning is created, without becoming a list of techniques disconnected from overall meaning.