Josquin de Prez

advertisement

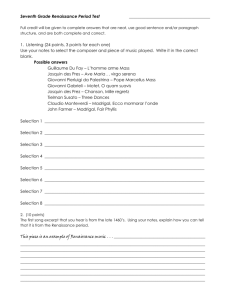

Josquin de Prez His revolutionary ways during the renaissance Andrew Bartlett 4/13/2012 1 Josquin de Prez Josquin de Prez was a revolutionary composer during the Renaissance (1450-1600). Not only was he famous during the time he was a live, he was famous after he died and still today in modern times. Josquin was one of the first Franco-Flemish composers that really began to change the way music was composed. Franco-Flemish means he was from the Netherlands region, and reflected somewhat on his approach to polyphonic music. He is often placed as the great composer between Guillaume Dufay and Palestrina. What sets him apart from his time is can be found in his many works of secular music, his motets such as Christum Ducem, and his chansons such as Cueurs desolez. Josquin’s music became widespread thanks to an Italian printer named Petrucci, however, over time there has been concern as to how many compositions he actually composed. Nevertheless, Josquin is rightly identified as the essence of Renaissance by many scholars today. The biography of Josquin is not very clear due to a lack of significant records. There have been a lot of presumptions about where he was born and when he was born based on other documented events in his life, but nothing that is 100% accurate. According to some artifacts such as his will, it can be determined that he was born a Frenchmen somewhere in the Dukes of Burgundy. It is estimated that he was born between 1450-1455, and died in 1521 on August 27th. While there may not be much information on his life, there is certainly plenty of information to be found about what he contributed to music during the Renaissance and into modern day (Burkholder, Grout, Palisca-2010: pg. 204). To understand how Josquin des Prez influenced music in the Renaissance, there must first be an understanding of what life and music was like before and during that time. Before the 2 Renaissance, religious music was still set with a high prestige that separated it from non-secular types of music. Machaut was the leading composer in the Ars Nova, and paved the way for polyphonic settings of masses with his Messe de Nostre Dame. The music was mostly treble dominated, which was very new to the Ars Nova. There was still a large use of parallel 5ths and octaves for cadences, and music was mostly isorhythmic and not too complex. The tenor line was used as a stable part, so that the other voices could sing above or below it and have a reference pitch. As the Renaissance began to emerge, the idea of humanism became a large part of how people viewed religious concepts and shifted views to favor Earthly observation instead of God. This shift in mindset provides a new range of music and new venues for performance. This applies specifically to those musicians who were on a paid salary in the court chapels of rulers, aristocrats, and church leaders. This was allowed because the musicians were paid by the rulers and not by the church, so they could be told to perform both secular entertainment and sacred functions. This mix of culture in music leads way for new compositions of secular music that begins to blend with the polyphonic techniques of non-secular music. The first big shift starts with the tenor acting as the heart of a polyphonic composition. This is different from the previous idea of the tenor being the voice which other voices could move around. In his article Music in the Culture of the Renaissance, Lowinsky states that Josquin was largely responsible for developing the means of using imitative style to create music (Lowinsky-1954: pg. 531). Imitative style gives the same musical theme to every voice in succession. This creates a very individualized line for each voice that has no direct ties to another voice, but at the same time they all have the fundamental musical theme that pulls them together. According to Bukofzer in Fauxbourdon Revisited, this largely pulls away from the 3 Cantus Firmus styles that were previously used to create polyphonic compositions, and leads to a new style where music wasn’t composed one line at a time starting with the Tenor (Bukofzer1952: pg. 38). Now, music was composed for each line simultaneously. What this brings to new compositions is a sense of perfection and unity between all the parts in a polyphonic composition that didn’t exist before. One example of this imitative style is in Jean Mouton’s composition of “Illuminare, illuminare Jherusalem”. Jean Mouton was another Renaissance composer that had taken many of Josquin’s styles and used them in his motets and other pieces. From the score book Si placet parts for motets by Josquin and his contemporaries, there is a modernized version of Jean’s score and in measures 108 – 118 are some examples of imitative style: see appendix one (Josquin, Schlagel-1521: pg. 118). Before it is explained where the imitation is, it is essential to understand what “Si placet” means. There are two parts that are labeled with [si placet] and this is because they were added over time to the original composition. They do not detract from the original in any way, but rather they compliment it, because it shows interest in the original composition and composers were still willing to analyze and work to make a great composition even better. In Jean’s composition, it is still fairly evident that imitation is in use because the entrances are very similar to each other. The text at the identified measures is “Et nos vernimus adorare Dominum” which translates to “And we have come to adore the Lord”. The order of the melodic lines begin with the Discantus secundus [si placet], then in the Discantus primus, Contratenor, Tenor secundus [si placet], Bassus, and finally Tenor primus all successively. The beginning melody is a whole note, followed by two half notes, a dotted half note, and a quarter note that leads up to another whole note (refer to attached music). With the si placet parts, there is a slight variation with the second half note being dotted instead of a regular half note. Every 4 part has this similar melodic pattern at different entrance times and even on different pitches. It is very interesting to see this technique used by another composer during the same time as Josquin, but that is just a way of showing how Josquin was popular during his time, and not just after he died and became a historical figure. Josquin’s motets are often considered to be the best of his works. With the diversity in texts, there was the ability to have more freedom with the music than there was to be had in the Masses. Most of the motets during this time were written for four voices, however, Josquin didn’t let the idea of composing for three and up to six voices over encumber him. A good example is in Josquin’s Miserere, which is a psalm motet written for five voices that was printed by Petrucci in 1519 (Josquin, Damrosch-1898 pg. 9,23,35). The motet is based on a simple canto fermo that is repeated one degree lower each time it appears in the first and third sections. In the second section it is repeated one degree higher: see appendix two. The publisher of the music Johannes Ott questioned if people would be able to identify this pattern just by listening to it because there was nothing that pointed it out or accented it. Aside from Johannes Ott’s concerns, this type of compositional technique helps to separate Josquin from his anonymous contributors. Perkins wrote in Josquin’s Qui habitat and the Psalm Motets that Josquin has a very unique compositional procedure that can be found in his motets (Perkins-2009). Perkins states in his book is that Josquin uses a “skillful and ingenious use of a variety of iterative procedures, including internal repetitions” to set his compositions apart from his other contemporaries. By looking at reliable motets, such as Josquin’s Miserere, theorists and analysts can compare different works to determine if it is a mere imitation of Josquin’s style, or if it is indeed Josquin’s brilliance. 5 Chansons were no exception when it comes to Josquin having an impact on the compositional style. There is a varied idea of how many chansons he composed vs. how many chansons were attributed to him, but the range is approximately 50-70 in total. Josquin’s new style started with his break away from the formes fixes, which is the repetitive patterns that are often found in rondeaus, virelais, and ballades. While he still set some of his chansons in the formes fixes he mostly composed freely as he would if he were composing a motet. In Cueurs desolez, one of Josquin’s five voice chansons, the voice singing the theme “Plorans ploravit in nocte” has a very distinct dramatic and sad/lamenting sound to it (Flamenca-2000). Josquin’s chansons are his only works that include this feature and he makes it very apparent to the listeners. Some of the ways he can make his works so filled with emotions is by texturizing the text and what he composes. For example, when there is a sad or lamenting sound, the music is slower, and there might be a solo voice or two singing homophonically. If the music is bright and uplifting, then all the voices will be singing with ornate polyphonic chords that portray a sense of happiness in the music (Burkholder, Palisca-2010: pg. 208-230). This largely characterizes French music and chansons by Josquin’s standards, and separates it from the style of the old Burgundian types of Chanson. So how did Josquin’s music become so popular all across Europe during his own lifetime? It was the invention of movable type and Ottaviano Petrucci that made this possible. In Mouser’s article Petrucci and his shadow: a case study of reception history, there are several descriptions of how Petrucci was able to make quality print and was able to disseminate it across Europe. Petrucci’s method of printing quality was unmatched by other printers of the time, because he used a triple press system where he first stamped the staves, then the music, and then the words. Petrucci was not only a quality printer, he also had a keen judgment of whose music 6 he should put into his books. Mouser points out in the study that over time, other publications of music books came out, and a large portion of them contained the same selection of music as Petrucci’s books (Mouser-2004: pg. 19-52). That is to say, Petrucci chose songs that became popular and continued to be performed and printed even after his death. Josquin was very fortunate in the fact that Petrucci decided to publish a great deal of Josquin’s work. According to Boorman’s book Ottaviano Petrucci: A Catalogue Raisonne, in 1514 Petrucci published Josquin’s book of masses, which happens to be one of the first books that was published with only one composer’s music inside (Boorman-2006). Petrucci was essential to boosting Josquin’s status as a brilliant composer during the Renaissance. Josquin was in fact so popular, that people were attributing their own compositions to Josquin’s name and getting them published in other books. This was done to help boost sales of a book, but in the long run of history it has caused some confusion as to what Josquin has actually composed, and what has been falsely attributed to him. Books such as Petrucci’s Canti B and other reliable books help to shed light on Josquin’s compositional styles to compare with other works of music in hopes of weeding out the songs that weren’t actually composed by him (Petrucci, Hewitt, Lowinsky-1967). The Renaissance was blessed with Josquin de Prez, and so are we now in a modern day sense. It was Josquin who helped revolutionize the way music was composed and performed then and now. His motet Miserere and Mouton’s Illuminare, illuminare Jherusalem are only two examples that were shown that contained Josquin’s imitative techniques and his brilliance for making his compositions his own in very unique ways. He was able to add emotions into music that were hard to find elsewhere such as in his chanson Cueurs desolez. Josquin was recognized 7 and famous during his own lifetime through the efforts of Petrucci, and he is famous today because of his many works that persist through time. 8 Citations Boorman, S. (2006). Ottaviano Petrucci: A Catalogue Raisonne. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Bukofzer, M.F. (1952) Fauxbourdon Revisited. The Musical Quarterly. Xxxviii, p. 38. Burkholder, J, Palisca, C. (2010). Norton anthology of western music (6th edition). New York London: W. W. Norton & Company. Burkholder, J, Grout, D, Palisca, C. (2010). A history of western music (8th edition). New York London: W.W. Norton & Company. Flamenca, C. (2000) Cueurs desolez. Oh Flanders Free: Flemish Renaissance music [cd]. Naxos Josquin des pres, Frank Damrosch (1898). G. Schirmers collection of oratorios and cantatas. Miserere mei Deus. New York: G. Schirmer. Josquin des prez, Schlagel S.P. (1521) Si placet parts for motets by Josquin and his contemporaries/edited by Stephanie P. Schlagel. Wisconsin, Middleton: A-R Editions. Lowinsky, E.E. (1954) Music in the culture of the renaissance. Journal of the History of Ideas, xv, p. 531. Mouser, M.J. (2004). Petrucci and his Shadow: A Case Study of Reception History. Fontes Artis Musicae, 51(1), 19-52. Perkins, L.L. (2009). Josquin’s Qui habitat and the Psalm Motets. Journal of musicology. Petrucci, O., Hewitt, H., & Lowinsky, E.E. (1967). Canti B Numero Cinquanta Venice, 1502. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.