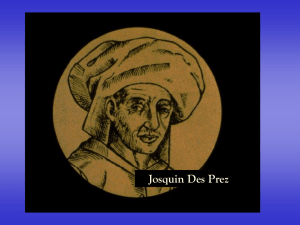

Josquin des Prez Bio

advertisement

Josquin des Prez (1440-1521) Josquin probably trained in or near Saint Quentin in northern France, halfway between Paris and Brussels. During the course of his life, he traveled extensively around Europe, a common practice for composers or musicians of such great reputation. He held a series of prestigious positions at courts and churches in France and Italy during his career. Josquin’s music was more than a little popular. For instance, Martin Luther, the religious reformer, liked Josquin’s music and proclaimed that he believed strongly in the educational and ethical power of such music. Part of Josquin’s fame during his lifetime came from printing his own music and distributing it—Gutenberg had invented the printing press around the time of Josquin’s birth. A Venetian called Petrucci was the first to publish and disseminate Josquin’s work. Josquin spent 60 years writing music, which seems like a very long time by any standards. He wrote 20 Masses, 100 motets, and 75 secular pieces. His work was considered central to the High Renaissance and a gateway to the Baroque. Though we do not know many details of his personal life, what we do know is just what Josquin's contemporaries knew: that he created wonderful music. What stands out most in his music is his care for the words. This is seen in part by the way he uses imitation to allow each voice to present the text before the texture becomes too dense to be clear. He also made use of homophonic textures to give the text an added clarity. Some of his works, especially his Masses, use the older cantus firmus technique. Here he uses the borrowed melody to create a huge scaffolding upon which he constructs the other melodies. Some of these pieces display a high level of technical complexity. At the same time, he could create pieces of marvelous simplicity and elegance, as he did so often in his motets and chansons. But Josquin's motets represent him at his best. By setting texts rarely touched by his predecessors or contemporaries (psalms, Gospel verses), he opened up new possibilities for musicians. By having the motet text generate melodic motives and thereby replace in function the traditional cantus firmus, he made the motet the harbinger of a new style. From most evidence it appears that Josquin turned to the writing of motets somewhat late in his career but composed them in large numbers after he turned away from the Mass. In Josquin's famed motet Ave Maria, probably composed in his middle (Roman) period, he consistently uses imitation. For each of several lines or phrases, he creates a unique musical motive that is imitated by each voice in turn. Sometimes a phrase is set to a pair of counter pointing voices that are in turn imitated by a second pair. For variety, chordal sections emphasizing the text alternate with those in imitation. A few motets like Domine Jesu Christe and Qui velatus facie fuisti are wholly chordal, but Josquin prefers, as in his Ave Maria, to alternate chordal with linear writing. This illustrates the composer's awareness of the text as an equal partner with the music.