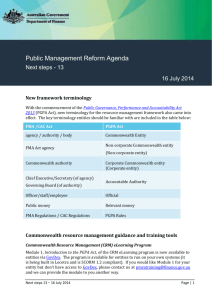

- Department of Finance

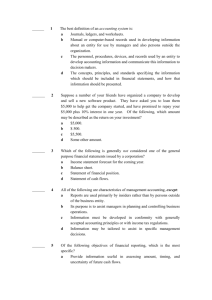

advertisement