1439037752_295897

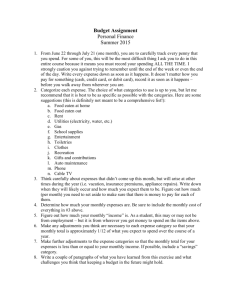

advertisement

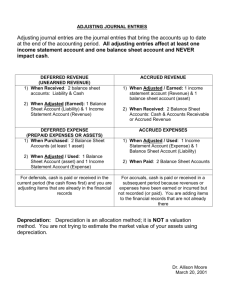

Chapter 12 1 Financial Statements, Closing Entries, and Reversing Entries College Accounting 10th Edition McQuaig McQuaig Bille Bille Nobles PowerPoint presented by Douglas Cloud Professor Emeritus of Accounting, Pepperdine University 12–1 © 2011 Cengage Learning The Income Statement Each of the amounts that appear in the Income Statement columns of the work sheet will be used in the income statement. The basic format of an incomes statement— Net Sales – Cost of Goods Sold = Gross Profit – Operating Expenses = Income from Operations 12–2 Gross Profit Contrasted with Net Profit Several years ago, Della Reyes bought an antique table at a second-hand store for $800. She sold the table for $1,850. She advertised in the daily newspaper at a cost of $73. How much did she clear as profit? Sale of Table $1,850 Less Cost of Table – 800 Gross Profit $1,050 Less Advertising Expense – 73 Net Income or Net Profit $ 977 12–3 Gross Profit Contrasted with Net Profit Gross Profit is the profit on the sale of the table before any expenses have been deducted. Net Income, or Net Profit, is the final or clear profit after all expenses have been deducted. Most accountants prefer Net Income. 12–4 Revenue from Sales Sales Returns and Allowances and Sales Discounts are deducted from Sales to give us Net Sales. Note that we record these items in the same order in which they appear in the ledger. 12–5 Gross Profit Percentage Net Sales is the 100 percent row 12–6 Gross Profit Percentage In 2010, for every $100 in net sales, cost of goods available for sale amounted to $59. $294,000 $500,000 12–7 Gross Profit Percentage In 2011, for every $100 in net sales, advertising expense amounted to $4. $21,400 $528,000 12–8 Gross Profit Percentage In 2010, for every $100 in net sales, net income amounted to $26. $132,000 $500,000 12–9 Cost of Goods Sold The section of the income statement that requires the greatest amount of concentration is the Cost of Goods Sold section. 12–10 Delivered Cost of Purchases First, let’s look closely at the Purchases section. To arrive at Net Purchases, we deduct the sum of Purchases Returns and Allowances and Purchases Discounts from Purchases. Then we add Freight In to get Delivered Cost of Purchases. 12–11 Cost of Goods Sold You might think of Cost of Goods Sold like this: Amount we started with (beginning inventory) + Net amount we purchased, including freight charges Total amount that could have been sold (available) ‒ Amount left over (ending inventory) Cost of the goods that were actually sold $ 67,000 87,920 $154,920 64,800 $ 90,120 Here’s the same Cost of Goods Sold expressed in proper wording: Merchandise Inventory, January 1, 20‒‒ + Delivered Cost of Purchases Cost of Goods Available for Sale ‒ Merchandise Inventory, December 31, 20‒‒ Cost of Goods Sold $ 67,000 87,920 $154,920 64,800 $ 90,120 12–12 Operating Expenses Selling Expenses are any expenses directly connected with the selling activity: Sales Salary Expense Sales Commissions Expense Advertising Expense Store Supplies Expense Delivery Expense Depreciation Expense, Store Equipment 12–13 Operating Expenses General Expenses are any expenses related to the office or administration, or any expense that cannot be directly connected with a selling activity: Office Salary Expense Property Tax Expense Depreciation Expense, Office Equipment Rent Expense Insurance Expense Office Supplies Expense 12–14 Income from Operations Net Sales – Cost of Goods Sold Gross Profit – Operating Expenses Income from Operations 12–15 Other Income and Other Expenses The Other Income classification includes any revenue account other than Sales. Typical accounts are as follows: Rent Income Interest Income Gain on Disposal of Equipment Miscellaneous Income The Other Expense classification includes various nonoperating expenses: Interest Expense Loss on Disposal of Equipment 12–16 The Statement of Owner’s Equity and the Balance Sheet Every figure in the Balance Sheet columns of the work sheet is used in either the statement of owner’s equity or the balance sheet. The income statement is prepared first, the statement of owner’s equity second, and the balance sheet last. 12–17 Balance Sheet for Whitewater Raft Supply 12–18 Current Assets Current Assets consist of cash and any other assets or resources that are expected to be realized in cash or to be sold or consumed during the normal operating cycle of the business (or one year, if the normal operating cycle is less than twelve months). Examples of accounts that are current assets include Cash, Notes Receivable, Accounts Receivable, and Merchandise Inventory. Notes Receivable (current) are short-term (one year or less) promissory notes (promise-to-pay notes) held by the firm. Prepaid Insurance and Supplies are considered prepaid items that will be used or will expire with the following operating cycle or one year. 12–19 Property and Equipment Property and Equipment are relatively long-lived assets that are held for use in the production or sale of other assets or services. Some accountants refer to them as fixed assets. Three accounts that usually appear in this category are Land, Building, and Equipment. Building and Equipment are followed by their respective Accumulated Depreciation accounts. 12–20 Current Liabilities Current Liabilities are debts that will become due within the normal operating cycle of the business, usually within one year. They normally will be paid, when due, from current assets. Three accounts that usually appear in this category are Notes Payable, Wages Payable, and Interest Payable. 12–21 Long-Term Liabilities Long-Term Liabilities are debts that are payable over a comparatively long period, usually longer than one year. The current portion of notes, contracts, and loans is shown as a current liability. An account that usually appears in this category is Mortgage Payable. 12–22 Working Capital and Current Ratio Working capital is the amount of capital a firm has available to use or to work with during a normal operating cycle Current Assets – Current Liabilities = Working Capital The Current ratio is useful in revealing a firm’s ability to pay its bills. It is calculated as follows: Current Assets (amount coming in within one year) Current Liabilities (amount going out within one year) 12–23 Working Capital and Current Ratio Two portions of Whitewater Raft Supply follow: 12–24 Working Capital Current Assets – Current Liabilities = Working Capital $123,355 ‒ $43,330 = $80,025 Current Ratio Current Assets = Current Ratio Current Liabilities Whitewater Raft $123,355 = 2.85 Supply has current $43,330 assets available to pay every dollar currently due on December 31. 12–25 Chart of Accounts The second digit in the chart of accounts stands for the subclassification. Assets: Current Assets Property and Equipment Liabilities Current Liabilities Long-Term Liabilities Owner’s Equity Capital 1-- Revenue 11- Revenue from Sales Other Income 12- Cost of Goods Sold 2-Purchases 21- Expenses 22- Selling Expenses 3-General Expenses 31- Other Expenses 4-41425-516-61626312–26 Closing Entries At the end of the fiscal period, you close the revenue and expense accounts so that you can start the next fiscal period with zero balances. You close the Drawing account because it, too, applies to one fiscal period. Recall that these accounts are called temporary-equity accounts, or nominal accounts. 12–27 Four Steps in the Closing Procedure STEP 1: Close the revenue accounts and the other accounts that appear on the income statement that have credit balances into Income Summary. 12–28 Four Steps in the Closing Procedure STEP 2: Close the expense and other accounts appearing on the income statement that have debit balances into Income Summary. Note that you close Sales Discounts and Sales Returns and Allowances along with the expense accounts. Four Steps in the Closing Procedure STEP 3: Close the Income Summary account into the Capital account, transferring net income or loss to the Capital account. 12–30 Four Steps in the Closing Procedure 12–31 Four Steps in the Closing Procedure STEP 4: Close the Drawing account into the Capital account. 12–32 Four Steps in the Closing Procedure 12–33 Reversing Entries Reversing entries are general journal entries that are the exact reverse of certain adjusting entries. A reversing entry enables the accountant to record routine transactions in the usual manner, even though an adjusting entry affecting one of the accounts involved in the transaction has intervened. 12–34 Reversing Entries Example All the employees of Mason Company earn, altogether, $400 per day for a five-day week and their payday occurs every Friday. Their current paychecks include wages for that Friday and for the preceding four days. The last day of the fiscal year falls on Wednesday, December 31. Wages Expense is debited and Cash is credited (ignoring taxes and deductions) $2,000. Wages Expense is debited and Cash is credited (ignoring taxes 12–35 and deductions) $2,000. Reversing Entries The following reversing entry is made on the first day of the following fiscal period (which is an exact reverse of the adjusting entry): 12–36 Reversing Entries Now, let’s follow the T accounts to see what happens. We begin with the adjusting entry at December 31. 12–37 Reversing Entries Next, we close Wages Expense (but not Wages Payable). Then we reverse the adjusting entry. 12–38 Reversing Entries Note that this gives Wages Expense a credit balance, and closes Wages Payable. 12–39 Reversing Entries On the first payday of the new fiscal period, the accountant can debit Wages Expense and credit Cash for $2,000 (just as if it was the middle of the fiscal year). After the payroll entry, there will now be a debit balance of $800 in Wages Expense, which is the correct amount. 12–40 Reversing Entries 12–41 Reversing Entries Rules If an adjusting entry is to be reversed, it must meet both of the following qualifications: 1. The adjusting entry increases an asset or liability account. 2. The asset or liability account did not have a previous balance. 12–42