PowerPoint Slides to Accompany Marketing Channels, 7th Edition

advertisement

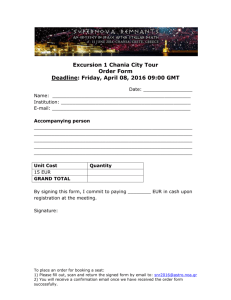

Anne T. Coughlan, Northwestern University Erin Anderson, INSEAD Louis W. Stern, Northwestern University Adel I. El-Ansary, University of North Florida FIGURE 1-1: CONTACT COSTS TO REACH THE MARKET WITH AND WITHOUT INTERMEDIARIES Manufacturers Selling Directly 40 Contact Lines Retailers Manufacturers Selling Through One Wholesaler Wholesaler Retailers Manufacturers 14 Contact Lines Selling Through Two Wholesalers Wholesalers 28 Contact Lines Retailers FIGURE 1.2: MARKETING FLOWS IN CHANNELS Producers Physical Possession Ownership Physical Possession Ownership Physical Possession Ownership Promotion Promotion Promotion Negotiation Financing Wholesalers Negotiation Financing Retailers Negotiation Financing Risking Risking Risking Ordering Ordering Ordering Payment Payment Payment Commercial Channel Subsystem Consumers Industrial and Household FIGURE 1-3: FRAMEWORK FOR CHANNEL DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION Channel Design Process: SEGMENTATION: Recognize and respond to target customers’ service output demands Channel Implementation Process: CHANNEL POWER: Identify sources for all channel members Decisions About Efficient Channel Response: CHANNEL STRUCTURE: What kinds of intermediaries are in my channel? Who are they? How many of them? SPLITTING THE WORKLOAD: With what responsibilities? DEGREE OF COMMITMENT: Distribution alliance? Vertical integration/ownership? GAP ANALYSIS: What do I have to change? CHANNEL CONFLICT: Identify actual and potential sources MANAGE/DEFUSE CONFLICT: Use power sources strategically, subject to legal constraints GOAL: Channel Coordination INSIGHTS FOR SPECIFIC CHANNEL INSTITUTIONS: Retailing, Wholesaling and Logistics, Franchising TABLE 1-1: SERVICE OUTPUT DEMAND DIFFERENCES (an example of segmentation in the book-buying market) Browser buying best-sellers to take on vacation Descriptor Service Output Demand Level Student buying textbooks for fall semester at college Descriptor Service Output Demand Level Bulkbreaking “I’m looking for some ‘good read’ paperbacks to enjoy.” Medium “I only need one copy of my Marketing textbook!” High Spatial convenienc e “I have lots of errands to run before leaving town, so I’ll be going past several bookstores.” Medium “I don’t have a car, so I can’t travel far to buy.” High Waiting and delivery time “I’m not worried about getting the books now… I can even pick up a few when I’m out of town if need be.” Low “I just got to campus, but classes are starting tomorrow and I’ll need my books by then.” High Assortment and variety “I want the best choice available, so that I can pick what looks good.” High “I’m just buying what’s on my course reading list.” Low Customer service “I like to stop for a coffee when book browsing.” High “I can find books myself, and don’t need any special help.” Low “I value the opinions of a well-read bookstore employee; I can’t always tell a good book from a bad one before I buy.” High “My professors have already decided what I’ll read this semester.” Low Informatio n provision Channel Design Process: Channel Implementation Process: SEGMENTATION: Chapter 2 CHANNEL POWER: Chapter 6 CHANNEL CONFLICT: Chapter 7 Decisions About Efficient Channel Response: CHANNEL STRUCTURE: Chapter 4 SPLITTING THE WORKLOAD: Chapter 3 DEGREE OF COMMITMENT: Chapters 8, 9 GAP ANALYSIS: Chapter 5 MANAGE/DEFUSE CONFLICT: Chapters 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 GOAL: Channel Coordination INSIGHTS FOR SPECIFIC CHANNEL INSTITUTIONS: Chapters 11, 12, 13 TABLE 2-1: ESTIMATED NUMBER OF U.S. CONSUMERS USING ONLINE BILL PAYMENT, VARIOUS YEARS YEAR # U.S. CONSUMERS PAYING AT LEAST 1 BILL ONLINE (millions, est.) % OF U.S. POPULATION (est.) 1998 3.4 1.3% … … … 2001 20.4 7.3% 2002 25.5 9.1% 2003 35 12.5% 2004 65 23% Notes: 1998: in 1998, just 2% of U.S. households used online bill payment, according to Tower Group (Bielski 2003). From U.S. Census data, in 1998, there were 100 million households in the U.S., with an average of 1.7 adults per household; thus, 2 million households or 3.4 million adults were using online bill payment in 1998. 2001: A Forrester Research report said that nearly 17 million U.S. households will pay bills online in 2002, up 41 percent from 2001 numbers (Higgins 2002). Thus, in 2001, 12 million U.S. households paid bills online. From U.S. Census data, there were 108 million households in the U.S., with an average of 2.58 adults per household; thus, there were 20.4 million adults using online bill payment in 2001. 2002: The same Forrester Research report said that nearly 17 million U.S. households will pay bills online in 2002 (Higgins 2002), while a Tower Group report said that 13.7% of U.S. households did pay bills online in 2002 (Bielski 2003). The table therefore reports the numbers from Bielski. There were 109 million households in the U.S. in 2002; thus, 15 million households paid bills online. Further, there were an average of 2.58 adults per household in the U.S. in 2002 (from U.S. Census data), yielding the estimate of 25.5 million adult online bill payers in 2002. 2003 and 2004: A Gartner study cites 65 million U.S. consumers paying at least some bills online, and reports this is almost twice as many as in 2003 (Park, Elgin et al. 2004). We therefore estimate that 35 million U.S. consumers paid bills online in 2003. OPTION: Paper Bill Payment Direct Biller Online Pay Third-Party Online Bill Payer (e.g. bank, Quicken) SET-UP PROCESS: None Consumer logs on to biller’s website; Enters information about account, name, bank account fr/which payment will be made, etc.; Picks a password, specific to this website, to gain access in future; Activation usually occurs within 24 hours Consumer logs on to third-party website; Enters information about each account individually; Picks a password, specific to this site but common across all bills paid at this site, to gain access in future BILL PRESENTMENT TO CONSUMER: Consumer receives bill through U.S. mail in envelope containing summary of bill charges & due date, payment stub, & payment envelope Either through U.S. mail (see paper bill) or electronic bill presentment through e-mail alert; both note payment due date Arrival of electronic bill noted through e-mail alert; Third party may/may not offer actual bill presentment CONSUMER BILL REVIEW AND PAYMENT AUTHORIZATION: Consumer reconciles bill with paper receipts; fills out payment stub; writes paper check; inserts check and stub in envelope; puts U.S. first-class stamp on envelope; mails payment Consumer reconciles bill with receipts; Visits biller website’s payment page; Enters amount and date of payment; [website indicates how fast payment will be made] Consumer visits third party’s website to view bill (if no presentment by third party) and reconcile; Enters amount and date of payment (may need up to 5 days to clear payment) CONFIRMATION OF PAYMENT TO CONSUMER: Only when next bill is received does consumer learn if previous payment was received in time (unless consumer telephones biller) Typically, e-mail confirmation of payment receipt the day payment is recorded Typically, e-mail confirmation that payment was made COST TO CONSUMER: Cost of first-class stamp; No cost to learn system; Cost of time to process bill & write check; Cost of paper check; Risk-adjusted cost of late payment (perceived very low) No monthly fee for payment processing No stamp; Initial learning time, for each biller’s system; Cost of time to check bill’s accuracy; No check writing or cost; Risk-adjusted cost of late payment (perceived low); No monthly fee for payment processing No stamp; Initial learning time, once for whole system; Cost of time to check bill’s accuracy; No check writing or cost; Risk-adjusted cost of late payments (moderate: up to 5 days to clear payment) May be a monthly fee (e.g., Quicken: $9.95/month for up to 20 bills, plus $2.49 per 5 bills thereafter; but many banks now do not charge for service); May be low cost to integrate with home financial records (e.g., Quicken financial software program) Respondents allocated 100 points among the following supplier-provided service outputs according to their importance to their c = Greatest Discriminating Attributes Lowest Total Cost/ Possible Service Pre-Sales Info Output Priorities Segment Responsive Support/ Post-Sales Segment = Additional Important Attributes Full-Service References and Relationship Segment Credentials Segment References and Credentials 5 4 6 25 Financial Stability and Longevity 4 4 5 16 Product Demonstrations & Trials 11 10 8 20 Proactive Advice & Consulting 10 9 8 10 Responsive Assistance During Decision Process 14 9 10 6 4 1 18 3 Lowest Price 32 8 8 6 Installation and Training Support 10 15 12 10 Responsive Problem Solving After Sale 8 29 10 3 Ongoing Relationship with a Supplier 1 11 15 1 100 100 100 100 16% 13% 61% 10% One-Stop Solution Total % Respondents Source: Reprinted with permission of Rick Wilson, Chicago Strategy Associates, 2000. FIGURE 2-1: IDEAL CHANNEL SYSTEM FOR BUSINESS-TO-BUSINESS SEGMENTS BUYING A NEW HIGH-TECHNOLOGY PRODUCT Manufacturer (New High Technology Product) Associations, Events, Awareness Efforts Pre-Sales Dealers Sales TeleSales/ TeleMktg VARs Internal Support - Install, Training & Service Group Post-Sales Segment Full-Service Responsive Support References/ Credentials ThirdParty Supply Outsource Lowest Total Cost Source: Reprinted with permission of Rick Wilson, Chicago Strategy Associates, 2000. Buyer’s Location Shipping Method Shipping Charge Time to Delivery United States Standard UPS $11.95 3 to 5 business days Mexico Surface Mail $20.00 8 to 12 weeks Mexico Priority Air $30.00 2 to 4 weeks Mexico UPS $50.00 1 to 2 weeks Source: www.landsend.com website. FIGURE 2-2: ADVERTISING COPY FOR AN AD FOR BN.COM Advertising Copy Service Output Offered “Really free shipping”: offers free shipping if 2 or more items are purchased. “We make it easy and simple.” Customer service “Fast & easy returns”: end-user can return unwanted books to a bricks-and-mortar Barnes & Noble bookstore. “Just try and return something to a store that isn’t there.” Quick delivery (for returns), spatial convenience; note implicit comparison with amazon.com, the pure-play online bookseller “Books not bait”: promises no additional sales pitches to buy non-book products. Assortment/variety: just books (targeting the book lover). Again, note implicit comparison with amazon.com. “Same day delivery in Manhattan”: delivery by 7:00 p.m. on any item(s) ordered by 11:00 a.m. that day. “No other online bookseller offers that.” Quick delivery: the offer is possible because of Barnes & Noble’s warehouses in New Jersey, near Manhattan. Note direct comparison with other online booksellers (notably, amazon.com) “The gift card that gives more”: can be used either online or in the bricks-and-mortar bookstores, nationwide. Spatial convenience, assortment/variety: when buying a gift for a friend, this provides virtually limitless assortment, and does so anywhere the recipient lives in the United States. “bn.com – 1,000,000 titles; amazon.com – 375,000 titles” Assortment/variety: direct comparison with amazon.com, offering a broader assortment of titles to the consumer Source: advertisement for bn.com in Wall Street Journal, November 20, 2002, p. A11. SERVICE OUTPUT DEMAND: SEGMENT NAME/ DESCRIPTOR BULK BREAKING SPATIAL CONVENIENCE DELIVERY/ WAITING TIME ASSORTMENT/ VARIETY CUSTOMER SERVICE INFORMATION PROVISION 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. INSTRUCTIONS: If quantitative marketing-research data are available to enter numerical ratings in each cell, this should be done. If not, an intuitive ranking can be imposed by noting for each segment whether demand for the given service output is high, medium, or low. Producers Physical Possession Ownership Physical Possession Ownership Physical Possession Ownership Promotion Promotion Promotion Negotiation Financing Wholesalers Negotiation Financing Retailers Negotiation Financing Risking Risking Risking Ordering Ordering Ordering Payment Payment Payment Consumers Industrial and Household Commercial Channel Subsystem The arrows above show flows of activity in the channel (e.g. physical possession flows from producers to wholesalers to retailers to consumers). Each flow carries a cost. Some examples of costs of various flows are given below: Marketing Flow Cost Represented Physical possession Storage and delivery costs Ownership Inventory carrying costs Promotion Personal selling, advertising, sales promotion, publicity, public relations costs, trade show costs Negotiation Time and legal costs Financing Credit terms, terms and conditions of sale Risking Price guarantees, returns allowances, warranties, insurance, repair, and after-sale service costs Ordering Order-processing costs Payment Collections, bad debt costs TABLE 3-1: CDW’S PARTICIPATION IN VARIOUS CHANNEL FLOWS Channel Flow CDW’s Investment in Flow Physical possession (a) CDW has a 400,000 sq. ft. warehouse. (b) CDW ships 99 percent of orders the day they are received. (c) For CDW’s gov’t buyers, CDW has instituted an “asset tagging” system that lets buyer track what product is going where; product is scanned into both buyer and CDW databases, for later ease in tracking products (e.g. for service calls) (d) CDW buys product in large volumes from mfgrs., taking in approximately eight trailer-loads of product from various suppliers every day. Loads are received in bulk, with few added services. Promotion (a) CDW devotes a salesperson to every account (even small, new ones!), so that an end-user can talk to a real person about technology needs, system configurations, post-sale service, etc. (b) Salespeople go through 6½ weeks of basic training, then 6 months of on-the-job coaching, then a year of monthly training sessions. (c) New hires are assigned to small-business accounts to get more opportunities to close sales. (d) Salespeople contact clients not through in-person sales calls (too expensive), but through phone/e-mail. (e) CDW has longer-tenured salespeople than its competitors. Negotiation (a) CDW-G started a small-business consortium in 2003 to help small firms compete more effectively for federal IT contracts. What CDW-G gives the small biz partner: lower prices on computers than they could otherwise get; business leads; and access to CDW’s help desk and product tools; CDW also handles shipping and billing, reducing the small biz partner’s channel flow burden. What the small biz partner provides: access to contracts CDW could not otherwise get. Financing (a) CDW collects receivables in just 32 days; CDW turns its inventories 2x per month; CDW has no debt. Risking (a) “We’re a kind of chief technical officer for many smaller firms”: (b) In April 2004, CDW was authorized as a Cisco Systems Premier (CSP) partner, in serving the commercial customer market. TABLE 3-2: PRODUCT RETURNS: A LARGE-SCALE PROBLEM Product Returns: A Large-Scale Problem The value of returned goods is close to $60-100 billion annually in the U.S. Web returns alone had value between $1.8 and $2.5 billion in 2002 Estimates are that the cost of processing those Web returns is twice as high as the merchandise value itself! U.S. companies are estimated to spend $35 billion to more than $40 billion per year on reverse logistics The average company takes 30-70 days to move a returned product back into the market The estimated number of packages returned in 2004 is 500 million Furthermore, returns are very significant in many industries. In a survey of over 300 reverse logistics managers in 1998, researchers found the following ranges for return percentages: TABLE 3-3: PRODUCT RETURNS: PERCENTAGE RANGES Industry Magazine Publishing Return % Ranges 50% Catalog Retailers 18-35% Book Publishers 20-30% Greeting Cards 20-30% CD-ROMs 18-25% Computer Manufacturers 10-20% Book Distributors 10-20% Mass Merchandisers 4-15% Electronic Distributors 10-12% Printers 4-8% Auto Industry (Parts) 4-6% Consumer Electronics 4-5% Mail Order Computer Manufacturers 2-5% Household Chemicals 2-3% TABLE 3-4: DIFFERENCES BETWEEN FORWARD AND REVERSE LOGISTICS Factor Difference Between Forward and Reverse Logistics Volume forecasting More difficult for returns than for original sales of new product Transportation Forward: ship in bulk (many of one SKU), with economies of scale. Reverse: ship many disparate SKUs in one pallet, no economies of scale. Product quality Forward: uniform product quality. Reverse: variable product quality, requiring costly evaluation of every returned unit. Product packaging Forward: uniform packaging. Reverse: packaging varies with some like-new, some damaged – no economies of scale in handling. Ultimate destination Forward: clear destination – to retailer or industrial distributor. Reverse: many options for ultimate disposition of product, necessitating separate decisions. Accounting cost transparency Forward: high. Reverse: low, because activities are not consistently tracked on a unified basis. Poor quality product, ships as spare parts to manufacturer Return for sale Manufacturer Return for credit Inspect, grade Manufacturer-run Return/Sorting Facility In sp ec t Re pa ir ,g ra de ab le pr od uc Retailer Return for refund Ins pec t, gra de Third-Party Returns/ Reverse Logistics Firm Repairable product t Repair/ Refurbishment Facility Hig h-q ua lity Consumer pro duc t Secondary Market, Broker, Jobber Charity Key: solid lines denote product to be salvaged for subsequent revenue. Dotted lines denote non-revenue-producing product flows. WEIGHTS FOR FLOWS: COSTS* BENEFIT POTENTIAL (High, Medium, or Low) FINAL WEIGHT * PROPORTIONAL FLOW PERFORMANCE OF CHANNEL MEMBER: 1 2 3 4 (end-user) TOTAL PHYSICAL POSSESSION** 100 OWNERSHIP 100 PROMOTION 100 NEGOTIATION 100 FINANCING 100 RISKING 100 ORDERING 100 PAYMENT 100 TOTAL 100 N/A 100 NORMATIVE PROFIT SHARE*** N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A 100 * Entries in column must add up to 100 points. ** Entries across row (sum of proportional flow performance of channel members 1 through 4) for each channel member must add up to 100 points. *** Normative profit share of channel member i is calculated as: (final weight, physical possession)*(channel member i's proportional flow performance of physical possession) + … + (final weight, payment)*(channel member i's proportional flow performance of payment). Entries across row (sum of normative profit shares for channel members 1 through 4) must add up to 100 points. Consumption Customer Retailers Wholesalers Manufacturers Suppliers Source: Based on the lecture notes of Enver Yücesan at INSEAD. WEIGHTS FOR FLOWS: COSTS BENEFIT POTENT IAL (High, PROPORTIONAL FLOW PERFORMANCE OF CHANNEL MEMBER: FINAL WEI GHT Mfgr. Retailer End-user TOTAL Medium, or Low) PHYSICAL POSSESSIO N 30 High 35 30 30 40 100 OWNERSHIP 12 Medium 15 30 40 30 100 PROMOTION 10 Low 8 20 80 0 100 NEGOTIATION 5 Low/Medium 4 20 60 20 100 FINANCING 25 Medium 29 30 30 40 100 RISKING 5 Low 2 30 50 20 100 ORDERING 6 Low 3 20 60 20 100 PAYMENT 7 Low 4 20 60 20 100 TOTAL 100 N/A 100 N/A N/A N/A N/A NORMATIVE PROFIT SHARE N/A N/A N/A 28% 39% 33% 100 WEIGHTS FOR FLOWS: PROPORTIONAL FLOW PERFORMANCE OF CHANNEL MEMBER: COSTS BENEFIT POTENTIAL (High, Medium, or Low) FINAL WEIGHT Mfgr. Retailer End-user TOTAL PHYSICAL POSSESSION 30 High 35 2 2 2 100 OWNERSHIP 12 Medium 15 2 2 2 100 PROMOTION 10 Low 8 1 3 0 100 NEGOTIATION 5 Low/Medium 4 1 2 1 100 FINANCING 25 Medium 29 2 2 2 100 RISKING 5 Low 2 2 2 1 100 ORDERING 6 Low 3 1 2 1 100 PAYMENT 7 Low 4 1 2 1 100 TOTAL 100 N/A 100 N/A N/A N/A N/A NORMATIVE PROFIT SHARE N/A N/A N/A ? ? ? 100 WEIGHTS FOR FLOWS: PROPORTIONAL FLOW PERFORMANCE OF CHANNEL MEMBER: COSTS BENEFIT POTENTIAL (High, Medium, or Low) FINAL WEIGHT Mfgr. Retailer End-user TOTAL PHYSICAL POSSESSION 30 High 35 33 33 33 100 OWNERSHIP 12 Medium 15 33 33 33 100 PROMOTION 10 Low 8 25 75 0 100 NEGOTIATION 5 Low/Medium 4 25 50 25 100 FINANCING 25 Medium 29 33 33 33 100 RISKING 5 Low 2 40 40 20 100 ORDERING 6 Low 3 25 50 25 100 PAYMENT 7 Low 4 25 50 25 100 TOTAL 100 N/A 100 N/A N/A N/A N/A NORMATIVE PROFIT SHARE N/A N/A N/A 32% 38% 29% 100 FIGURE 4- 1: SAMPLE REPRESENTATIONS OF THE COVERAGE/MARKET SHARE RELATIONSHIP FOR FAST MOVING CONSUMER GOODS 100% D C Brand Market Share B A “normal” expectation 100% Extent of Dis tribution Coverage for a Brand (% of all Poss ible Outlets ) Function A is an example of the type of relationship that would ordinarily be expected between distribution coverage and market share. Functions B, C and D are convex and are examples of approximate relationships often found in FMCG markets. A brand can achieve 100% market share at less than 100% coverage because not every possible outlet will carry the product category. For example, convenience stores sell food but not every category of food. Based on Reibstein, David J., and Paul W. Farris (1995), "Market Share and Distribution: A Generalization, A Speculation, and Some Implications," Marketing Science, 14 (3), G190-G202. FIGURE 4- 2: : SELECTIVE COVERAGE--THE MANUFACTURER’S CONSIDERATIONS For For the the Manufacturer Manufacturer Limited coverage is currency More selectivity = more money Exclusive distribution = Manufacturers use the money to “pay” the Channel Members for : - limiting its own coverage of brand in product category (gaining exclusive dealing is very expensive) - supporting premium positioning of the brand - finding a narrow target market - coordinating more closely with the manufacturer - making-supplier specific investments • new products • new markets • differentiated marketing strategy requiring downstream implementation - accepting limited direct selling by manufacturer - accepting the risk of becoming dependent on a strong brand Manufacturers need to “pay more” when : - the product category is important to the Channel Member - the product category is intensely competitive FIGURE 4- 3: CATEGORY SELECTIVITY: THE DOWNSTREAM CHANNEL MEMBERS’ CONSIDERATIONS For For the the Downstream Downstream Channel Channel Member Member Limiting brand assortment is currency Fever brand = more money Exclusive dealing = Downstream Channel Members use the money to “pay” the supplier for : - limiting the number of competitors who can carry the brand in the Channel Member’s trading area - providing desired brands that fit the Channel Member’s strategy - wording closely to help the Channel Member achieve competitive advantage - making Channel-Member-specific investments • new products • new markets • differentiated Channel Member strategy requiring supplier cooperation - accepting the risk of becoming dependent on a strong Channel Member Downstream Channel Members need to “pay more” when : - the trading area is important to the supplier - the trading area is intensely competitive FIGURE 5-1: THE GAP ANALYSIS FRAMEWORK SOURCES OF GAPS Environmental Bounds: Local legal constraints Local physical, retailing infrastructure Managerial Bounds: Constraint due to lack of knowledge Constraint due to optimization at a higher level TYPES OF GAPS Demand-Side Gaps: SOS < SOD SOS > SOD Which service outputs? Supply-Side Gaps: Flow cost is too high Which flow(s)? CLOSING GAPS Demand-Side Gaps: Offer tiered service levels Expand/contract provision of service outputs Change segment(s) targeted Supply-Side Gaps: Change flow responsibilities of current channel members Invest in new low-cost distribution technologies Bring in new channel members FIGURE 5-2: ONLINE BILLING AND PAYMENT: GAP ANALYSIS BOUNDS GAPS CLOSING THE GAPS Environmental: Technology infrastructure: takes time to fully develop initially endowed benefits more on billers than on payers is not universally available is characterized by high fixed set-up costs, but low marginal implementation costs and thus is not attractive unless significant scale is achieved Demand-side: Assortment/variety (one-stop bill payment site not available) Waiting time too long (some e-bills took 5 days to pay) Information provision poor (thus e-bill payment viewed as risky) Supply-side: Clear lowering of many channel flow costs But consumer (as a channel member) bears more perceived risk, with no compensating price cut Cost cuts initially much more available to biller than to payer (asymmetric cost efficiencies that hamper adoption) Relax environmental bounds: Build software applications to generate back-office benefits for B2B players Presentment technology eventually developed to improve assortment/variety for consumer payers Increase promotional efforts generate information for consumers Add new specialist channel members New specialists develop new technology to provide integrated benefits to consumers and B2B payers Consumers adopt e-bill payment Banks, billers increase promo efforts to publicize e-bill payment; may even cut cost to consumer Scale goes up at biller or bank Due to economies of scale, per-transaction cost of offering e-bill payment falls Note: the B2B process exhibits a similar path, with the added inducement to payers of the development of technologies to integrate bill payment information with backoffice (accounts payable, inventory management, and ordering) processes. Sources of Gaps: Environmental Bounds: Managerial Bounds: Infrastructure for managing returns is not as well developed as for forward logistics. Many manufacturers lack information about scope of problem and how much money they are losing by not managing it better. Types of Gaps: Demand-Side Gaps: Supply-Side Gaps: Customer service: end-users may be dissatisfied when charged a restocking fee, as many are not widely publicized. Quick delivery: end-users fail to get their desired product quickly when they have to return it for exchange or refund. Physical possession, ownership, and financing: returned product held in the system for 30-70 days before returning to the market for resale adds to all of these costs. Promotion: when returned product is sent to a liquidator, it is likely to end up in a channel competitive to the new-goods market, creating brand confusion and promotional inefficiency. Risking: uncertainty on both the supply (demand forecasting) and demand (what product is right for me?) sides Payment: returns trigger multiple new payment flows, to end-user (who returns product), to retailer (who gets money back from original invoice paid to manufacturer), and to third-party disposal or logistics firms. Closing Gaps: Demand-Side Gaps: Efforts to minimize returns improve on quick delivery. Supply-Side Gaps: Effective third-party logistics specialists not only handle returned product faster, but also repackage and re-kit it to sell through non-competing new channels. 5 3,6 1,4 2,7 KEY: 1,4: Lebanon, Indiana 2,7: Marina del Rey, California 3,6: Jamesburg, New Jersey 5: Bridgewater, Massachusetts TOTAL DISTANCE: 9,600 MILES TABLE 5-1: U.S. RETAIL MUSIC SALES, 1999-2003 Year Sales in $billion 1999 $14.6 2000 $14.3 2001 $13.7 2002 $12.8 2003 $11.8 Time Period Average Price 2002 (Q1) $13.90 2002 (Q2) $13.90 2002 (Q3) $13.60 2002 (Q4) $13.90 2003 (Q1) $13.80 2003 (Q2) $13.70 2003 (Q3) $13.50 2003 (Q4) $13.55 2004 (Q1) $13.25 TABLE 5-3: SHARE OF ALBUMS SOLD BY CHANNEL, 2002 Channel Share of Albums Sold Music chain stores 51.0% Mass merchants 33.8% Independents 11.9% Other 3.3% Notes: 680.9 million albums were sold in total in 2002. Mass merchant channel includes Best Buy, Kmart, Wal-Mart, Costco, and Target. COST PERFORMANCE LEVEL: Demand-side Gap (SOD>SOS) No DemandSide Gap (SOD=SOS) Demand-side Gap (SOS>SOD) Price/value Price/value No Supply-Side proposition=right proposition=right No Gaps Gap (Efficient for a less for a more Flow Cost) demanding demanding segment! segment! Supply-side Gap Insufficient SO High cost, but High costs and (Inefficiently High provision, at high SO’s are right: SO’s=too high: Flow Cost) costs: price &/or value is good, but no extra value cost too high, price &/or cost is created, but price value too low high &/or cost is high 45 Total Cost as a Function of Delivery Time 40 G 35 30 Cost 25 End-User's Cost of Holding Goods A E 20 F 15 B 10 Cost of Moving Goods to the End-User 5 C D 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 Delivery Time Source: Adapted from Louis P. Bucklin, A Theory of Distribution Channel Structure (Berkeley, CA: IBER Publications, University of California, 1966), pp. 22-25. SERVICE OUTPUT LEVEL DEMANDED (SOD) VERSUS SERVICE OUTPUT LEVEL SUPPLIED (SOS) SEGMENT NAME/ DESCRIPTO R BULK BREAKING SPATIAL CONVENIENC E DELIVERY/ WAITING TIME ASSORTMEN T/ VARIETY CUSTOMER SERVICE INFORMATIO N PROVISION MAJOR CHANNEL FOR THIS SEGMENT 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Notes and directions for using this template: Enter names and/or descriptions for each segment. Enter whether SOS>SOD, SOS<SOD, or SOS=SOD for each service output and each segment. Add footnotes to explain entries if necessary. If known and relevant, footnote can record any supply-side gaps that lead to each demand-side gap. Record major channel used by each segment, i.e., how does this segment of buyers choose to buy? CHANNEL [targeting which segment(s)?] CHANNEL MEMBERS AND FLOWS THEY PERFORM ENVIRONMENTAL/ MANAGERIAL BOUNDS SUPPLY-SIDE GAPS [affecting which flow(s)?] PLANNED TECHNIQUES FOR CLOSING GAPS DO/DID ACTIONS CREATE OTHER GAPS? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Notes: Record routes to market in the channel system. List should include all channels recorded in Figure 5-4 above. Note the segment or segments targeted through each channel. Summarize channel members and key flows they perform (ideally, link this to the Efficiency Template analysis in Chapter 3). Note any environmental or managerial bounds facing this channel. Note all supply-side gaps in this channel, by flow or flows affected. If known, record techniques currently in use or planned for use to close gaps (or note that no action is planned, and why). Analyze whether proposed/actual actions have created or will create other gaps. SERVICE OUTPUT LEVEL DEMANDED (SOD: L/M/H) VERSUS SERVICE OUTPUT LEVEL SUPPLIED BY CDW (SOS) SEGMENT NAME/ DESCRIPTO R BULK BREAKING SPATIAL CONVENIENCE DELIVERY/ WAITING TIME ASST/ VARIETY 1. Small business buyer H (SOS=SOD) Original equipment: M (SOS=SOD) Post-sale service: H (SOS=SOD) Original equipment: M (SOS>SOD) Post-sale service: H (SOS=SOD) M (SOS>SOD) 2. Large business buyer L (SOS>SOD) Original equipment: H (SOS=SOD) Post-sale service: L (SOS>SOD) Original equipment: M (SOS>SOD) Post-sale service: L (SOS>SOD) 3. Gov’t/ education L (SOS>SOD) Original equipment: H (SOS=SOD) Post-sale service: H (SOS=SOD) Original equipment: M (SOS>SOD) Post-sale service: M (SOS>SOD) CUSTOMER SERVICE INFORMATIO N PROVISION MAJOR CHANNEL FOR THIS SEGMENT H (SOS=SOD) H (both pre-sale and post-sale) (SOS=SOD) Value-added reseller like CDW, or retailer M/H (SOS=SOD) M (SOS>SOD) L (SOS>SOD) Manufacturer direct, or large reseller like CDW M/H (SOS=SOD) H (SOS=SOD) H (both pre-sale and post-sale) (SOS=SOD) Manufacturer direct, or reseller; 23 percent from small business (VARs) CHANNEL [targeting which segment(s)?] CHANNEL MEMBERS AND FLOWS THEY PERFORM* ENVIRONMENTAL (E) / MANAGERIAL (M) BOUNDS SUPPLY-SIDE GAPS [affecting which flow(s)?] PLANNED TECHNIQUES FOR CLOSING GAPS DO/DID ACTIONS CREATE OTHER GAPS? 1. CDW direct to buyer ( small business buyer) Manufacturer; CDW; Sm. Bus. Buyer (M): no screening of recruits for expected longevity with firm Promotion [sales force training/turnover] Better screening of new recruits No Buying from CDW closes gaps for customer in Risking 2. CDW direct to buyer ( large business buyer, government) Manufacturer; CDW, CDW-G; Lg. Bus. Buyer or Government Buyer (E): government requires 23 percent of purchases from small vendors (M): no screening of recruits for expected longevity with firm Promotion [sales force training/turnover] Negotiation [cannot close 23% of deals with government] Better screening of new recruits; Rely on consortium channel structure (below) No 3. CDW + small business VAR consortium member ( government) Manufacturer; CDW-G; Small VAR; consortium partner Government Buyer (E): government requires 23 percent of purchases from small vendors; (M): VAR’s small business size (M): no screening of recruits for expected longevity with firm Promotion [sales force training/turnover]; (Negotiation: only a gap for a small VAR not in the CDW alliance) Better screening of new recruits; Negotiation gap above is closed through consortium with small VARs No Note: all channel members perform all flows to some extent. Key channel flows of interest are promotion, negotiation, FIGURE 6-1 THE NATURE AND SOURCES OF CHANNEL POWER A’s Level of Investment In : Reward Coercion Legitimacy Expertise Reference UTILITY DERIVED BY B FROM A A’s Offering to B: Reward Dependence of B on A Coercive Legitimacy Expertise Referent Competitive Levels Of: Reward Coercion Power of A over B SCARCITY OF B’s ALTERNATIVES TO A Legitimacy Expertise Reference B’s access to A’s competitors FIGURE 6-2 USING POWER TO EXERT INFLUENCE Power Source(s) Necessary Influence Strategy for this to Work 1. Promise Reward 2. Threat Coercive 3. Legalistic Legitimate 4. Request Referent, Reward, Coercive 5. Info Exchange Expertise, Reward 6. Recommendation Expertise, Reward Supplier Goals Financial Reseller Viewpoint Viewpoint Maximize own profit - Higher prices to reseller - Higher sales Maximize own by profit - Higher own by reseller (lower prices from our and higher prices to our ) - Higher reseller expenses - Lower expenses - Higher reseller inventory - Faster inventory Target ( less too high . : You don’t Reseller support) effort are support me money . enough , we can’t make . turnover stocks) from manufacturers on : - Segment Accounts - Multiple on : Focus - Multiple segments markets - Many accounts ( raise put enough Your prices - Higher allowances reseller Focus Desired brand. With your wholesale prices (lower reseller to behind my supplier of Clash : You don’t Supplier by -level margins customer - Lower allowances Expression corresponding Supplier to resellers’ positioning more effort. Our (e.g. discounter) for us. - Our Reseller markets only - Selected accounts volume and share ) (those that strategy more : We need coverage and reseller doesn’t : You don’t respect . We need do enough our marketing to make money too . too many lines . You are profitable to serve) Desired Product - Concentrate And Accounts product category Policy our brand - Carry on our our full conceivable need * Based on Magrath and Hardy scope over product categories don’t give line - Serve every brand assortment , plus to expand our line outside our traditional strenghts Supplier disloyal (a variation for efforts and - Achieve economies of ) (1989) our customers by offering - Do not carry slow- moving supplier (every these ) Reseller : You carry us enough or By the way has some of , you will benefit , shouldn’t you consider pruning your product line items You’re : Our customers come first satisfy our customers inferior attention. . ? . If we . FIGURE 8-1: SYMPTOMS OF COMMITMENT IN MARKETING CHANNELS A committed party to a relationship (a manufacturer, a distributor, or another channel member) views its arrangement as a long-term alliance. Some manifestations of this outlook show up in statements such as these, made by the committed party about its channel partner. • We expect to be doing business with them for a long time. • We defend them when others criticize them. • We spend enough time with their people to work out problems and misunderstandings. • We have a strong sense of loyalty to them. • We are willing to grow the relationship. • We are patient with their mistakes, even those that cause us trouble. • We are willing to make long-term investments in them, and to wait for the payoff to come. • We will dedicate whatever people and resources it takes to grow the business we do with them. • We are not continually looking for another organization as a business partner to replace or add to this one. • If another organization offered us something better, we would not drop this organization, and we would hesitate to take on the new organization. Clearly, this is not normal operating procedure for two organizations. Commitment is more than having an ongoing cordial relationship. It involves confidence in the future, and a willingness to invest in the partner, at the expense of other opportunities, in order to maintain and grow the business relationship. FIGURE 8-2: MOTIVES TO CREATE AND MAINTAIN STRATEGIC ALLIANCES IN CHANNELS Motives to Ally Strategically The Upstream Channel Member The Downstream Channel Member Fundamentals Motivate downstream channel members to represent them better In current markets With current products In new markets With new products Avoid stockouts while keeping costs under control Lower costs of all flows performed, such as lower inventory holding costs Generate customer preference Coordinating marketing efforts more tightly with downstream channel members Get closer to customers and prospects Enhance understanding of the market Coordinating marketing efforts more tightly with upstream channel members Serve the customer better Convert prospects into customers Net effect: higher volume and margins Preserving choice and flexibility of channel partners Guaranteeing market access in the face of consolidation in wholesaling Keep routes to market open Rebalance power between the producer and surviving channels Assure a stable supply of desirable products, even as manufacturers consolidate In current markets Selling current products Opening to new markets With new products Strategic pre-emption Erecting barriers to entry to other brands Induce channels to refuse access Induce channels to offer low levels of support to entrants Differentiate themselves from other downstream channel members Supplier’s preferred outlet Value-added services, difficult to copy and of high value to their customers Superordinate Goal Enduring competitive advantage leading to profit Reduce accounting and opportunity costs Enduring competitive advantage leading to profit Reduce accounting and opportunity costs Supplier’s Guess: How committed is this distributor to me? Supplier’s Commitment to a Distributor Distributor’s Commitment to a Supplier Distributor’s Guess: How committed is this supplier to me? Relationship Phas e 1: Awarenes s Relationship Phase 2: Exploration Relationship Phase 3: Expans ion Relationship Phase 4: Commitment Relationship Phas e 5: Decline and Diss olution • One organization sees another as a feas ible exchange partner • Little interaction • Networks are critical : one player recommends another • Physical proximity matters: parties more likely to be aware of each other • Experience with transactions in other domains (other products, markets , functions) can be us ed to identify parties • Testing, probing by both s ides • Inves tigation of each other’s natures and motives • Interdependence grows • Bargaining is intens ive • Selective revealing of information is initiated and mus t be reciprocated • Great s ensitivity to is sues of power and justice • Norms begin to emerge • Role definitions become more elaborated • Key feature: each s ide draws inferences and tests them • This phase is eas ily terminated by either side • Benefits expand for both s ides • Interdependence expands • Each party inves ts to build and maintain the relations hip • Long time horizon • Parties may be aware of alternatives but do not court them • High expectations on both s ides • High mutual dependence • High trus t • Partners resolve conflict and adapt to each other and to their changing environment • Shared valves and/or contractual mechanis ms (s uch as s hared risk) reinforce mutual dependence • Key features: loyalty, adaptability, continuity, high mutual dependence s et these relations hips apart • Tends to be s parked by one s ide • Mounting diss atis faction leads one s ide to hold back inves tment • Lack of investment provokes the other s ide to reciprocate • Dis solution may be abrupt but is us ually gradual • Key feature: it takes two to build but only one to undermine. Decline often s ets in without the two parties’ realization 1 2 3 • Ris k taking increases • Satis faction with res ults leads to greater motivation and deepening commitment • Goal congruence increas es • Cooperation increases • Communication increas es • Atlernative partners look less attractive • Key feature: momentum mus t be maintained . To progres s, each party mus t s eek new areas of activity and maintain cons istent efforts to create mutual payoffs 4 5 FIGURE 9-1: THE CONTINUUM OF DEGREES OF VERTICAL INTEGRATION Buy Classical Market Contracting Third Party Does it (for a price) Their people Their money Their risk Their responsibility Their operation (control) Their gain or loss Make Quasi-Vertical Integration (Relational Governance) How does the the work get done The costs You and third party share costs and benefits The benefits Vertical Integration You do it Your people Your money Your risk Your responsibility Your operation (control) Your gain or loss Function Classical Market Contracting 1) Selling (only) Manufacturers’ Representatives 2) Wholesale Distribution Independent Wholesaler 3) Independent (3rd party) Retail Distribution Quasi-vertical Integration “Captive” or Exclusive Sales Agency * Distribution Joint Venture Franchise Store Vertical Integration Producer Sales Force (direct sales force) Distribution Arm of Producer Company Store * Operationally, a sales agency deriving more than 50% of its revenues from one principal Highly Volatile Market Low Specificity Outsource Distribution to Retain Flexibility Until Uncertainty Is Reduced High Specificity Highly Promising Market Vertically Integrate to Gain Control Over Employees And Avoid Small-Numbers Bargaining In Changing Circumstances Less Promising Market Do Not Enter Step 2: Question Outsourcing Where Markets Are Not Competitive: Step 1: Outsourcing Distribution to Benefit from Advantages of Competitive Markets: + Revenues + • Motivation • Specialization • Survival of the Economic Fittest • Economies of Scale • Heavier Coverage • Independence from a Single Producer 1) Valuable Company-Specific Capabilities are Needed: • Know-How • Relationships • Brand Equity Created by Distribution Activities • Dedicated Capacity • Site Specificity • Customized Physical Facilities 2) Thin Supply - - Direct Costs Overhead - Step 3: Question Outsourcing Where Indicators of Results Do Not Correspond to Performance: + • Cannot be benchmarked • Not Timely • Inaccurate FIGURE 10-1: PRINCIPAL U.S. FEDERAL LAWS AFFECTING MARKETING CHANNEL MANAGEMENT Act Key Provisions Sherman Antitrust Act, 1890 1.Prohibits contracts, combinations, or conspiracies in restraint of interstate or foreign commerce. Clayton Antitrust Act, 1914 Where competition is, or may be, substantially lessened, it prohibits: 1.Price discrimination in sales or leasing of goods 2.Exclusive dealing 3.Tying contracts 4.Interlocking directorates among competitors 5.Mergers and acquisitions. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Act, 1914 1.Prohibits unfair or deceptive trade practices injurious to competition or a competitor. 2.Sets up FTC to determine unfairness. Robinson-Patman Act, 1936 1.Discriminatory prices for goods are prohibited if they reduce competition at any point in the channel. 2.Discriminatory prices can be given in good faith to meet competition. 3.Brokerage allowances are allowed only if earned by an independent broker. 4.Sellers must give all services and promotional allowances to all buyers on a proportionately equal basis if the buyers are in competition. The offering of alternatives may be necessary. 5.Buyers are prohibited from knowingly inducing price or promotional discrimination. 6.Price discrimination can be legal if it results from real cost differences in serving different customers. FTC Trade Practice Rules 1.Enforced by FTC. Defines unfair competition for individual industries. These practices are prohibited by the FTC. 2.Defines rules of sound practice. These rules are not enforced by the FTC, but are recommended. FIGURE 10-2: LEGAL RULES USED IN ANTITRUST ENFORCEMENT Per se illegality: The marketing policy is automatically unlawful regardless of the reasons for the practice and without extended inquiry into its effects. It is only necessary for the complainant to prove the occurrence of the conduct and antitrust injury. Modified rule of reason: (also called "Quick Look") The marketing policy is presumed to be anticompetitive if evidence of the existence and use of significant market power is found, subject to rebuttal by the defendant. Rule of reason: Before a decision is made about the legality of a marketing policy, it is necessary to undertake a broad inquiry into the nature, purpose, and effect of the policy. This requires an examination of the facts peculiar to the contested policy, its history, the reasons why it was implemented, and its competitive significance. Per se legality: The marketing policy is presumed legal. Retailer (by rank; home country) (rank in 1998) Retail Formats 2003 Retail Sales (US$ million) 5 Year Retail Sales Compound Annual Growth Rate 1. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. (USA) (1) Discount, Hypermarket, Supermarket, Superstore, Warehouse 256,329 13.2% 2. Carrefour (France) (8) Cash & Carry, Convenience, Discount, Hypermarket, Specialty, Supermarket 79,796 20.8% 64,816 16.5% 60,503 3.1% 53,791 14.4% 51,535 12.5% 46,781 8.9% 44,584 10.7% 41,693 11.8% 40,060e 14.4% 3. Home Depot (USA) (16) 4. Metro (Germany) (2) 5. Kroger (USA) (3) 6. Tesco (UK) (18) 7. Target (USA) (ii) 8. Ahold (Netherlands) (5) 9. Costco (USA) (24) 10. Aldi Einkauf (Germany) (17) DIY Cash & Carry, Department, DIY, Food Service, Hypermarket, Specialty, Superstore Convenience, Discount, Specialty, Supercenter, Supermarket, Warehouse Convenience, Department, Hypermarket, Supermarket, Superstore Department, Discount, Supercenter Cash & Carry, Convenience, Discount, Drug, Hypermarket, Specialty, Supermarket Warehouse Discount, Supermarket Number of Countries; On Which Continents (i) 10 (N. Am., S. Am., Asia, Eur.) 30 (Af., S. Am., Asia, Eur.) 4 (N. Am.) 28 (Af., Asia, Eur.) 1 (N. Am.) 12 (Asia, Eur.) 1 (N. Am.) 21 (N. Am., C. Am., S. Am., Asia, Eur.) 9 (N. Am., S. Am., Asia, Eur.) 12 (N. Am., Eur., Pac.) 11. Rewe (Germany) (12) 12. Intermarche (France) (4) 13. Sears (USA) (6) 14. Safeway, Inc. (USA) (19) 15. Albertson’s (USA) (9) 16. Schwarz Group (Germany) (36) Cash & Carry, Discount, DIY, Drug, Hypermarket, Specialty, Supermarket, Superstore Cash & Carry, Convenience, Discount, DIY, Food Service, Specialty, Supermarket, Superstore Department, Mail Order, Specialty Supermarket Convenience, Drug, Supermarket Discount, Hypermarket, Superstore 17. Walgreens (USA) (31) Drug 18. Auchan (France) (21) Department, DIY, Hypermarket, Specialty, Supermarket, Superstore 19. Lowe’s (USA) (40) DIY 20. Ito-Yokado (Japan) (23) Convenience, Department, Food Service, Specialty, Supermaket, Superstore Cash & Carry, Discount, DIY, Drug, Hypermarket, Specialty, Supermarket, Superstore Convenience, Drug, Department, Discount, DIY, Food Service, Specialty, Supermarket, Superstore 21. Tengelmann (Germany) (13) 22. AEON (Japan) (n.l.) 38,931e 1.5% 37,472e 204% 36,372 -2.5% 35,553 7.7% 35,436 17.2% 33,435e 22.4% 32,505 16.3% 32,497 1.4% 30,838 20.3% 30,819 4.4% 4 (N. Am., Asia) 29,091e -2.0% 15 (N. Am., Asia, Eur.) 28,697 6.9% 11 (N. Am., Asia, Eur.) 13 (Eur.) 7 (Eur.) 3 (N. Am.) 3 (N. Am.) 1 (N. Am.) 17 (Eur.) 1 (N. Am.) 12 (Af., S. Am., Asia, Eur.) 1 (N. Am.) 23. J. Sainsbury (UK) (20) 24. Edeka (Germany) (11) Convenience, Hypermarket, Supermarket, Superstore Cash & Carry, Convenience, Discount, DIY, Specialty, Supermarket, Hypermarket, Superstore 25. E. Leclerc (France) (22) Convenience, Hypermarket, Supermarket 26. CVS (USA) (32) Drug 27. Casino (France) (33) Cash & Carry, Convenience, Department, Discount, Food Service, Hypermarket, Specialty, Supermarket, Warehouse 28. Best Buy (USA) (51) Specialty 29. Kmart (USA) (10) Discount, Superstore 30. Delhaize Group (Belgium) (34) 31. Woolworths (Australia) (48) Cash & Carry, Convenience, Drug, Specialty Convenience, Department, Specialty, Supermarket 32. J.C. Penney (USA) (15) Department, Mail Order 33. KarstadtQuelle (Germany) (47) 34. AutoNation (USA) (n.l.) Department, Food Service, Mail Order, Specialty 35. Publix (USA) (46) Convenience, Supermarket Auto 28,630 1.0% 28,330e -3.1% 27,396e 5.7% 26,588 11.7% 26,018 10.6% 24,547 19.5% 23,253 -7.1% 21,306 7.8% 19,941 10.6% 17,786 -9.7% 16,976 -2.3% 16,867 5.9% 16,848 6.9% 2 (N. Am., Eur.) 5 (Asia, Eur.) 6 (Eur.) 1 (N. Am.) 19 (N. Am., S. Am., Asia, Eur.) 2 (N. Am.) 1 (N. Am.) 10 (N. Am., Asia, Eur.) 2 (Pac.) 3 (N. Am., S. Am.) 23 (N. Am., Eur.) 1 (N. Am.) 1 (N. Am.) 36. Rite Aid (USA) (44) 37. Coles Myer (Australia) (43) 38. Gap (USA) (57) 39. Pinault-PrintempsRedoute (France) (52) 40. Federated Department Stores (USA) (29) 41. Safeway (UK) (45) 42. Daiei (Japan) (25) 43. Kingfisher (UK) (30) 44. El Corte Ingles (Spain) (70) 45. Marks & Spencer (UK) (38) Drug Convenience, Department, Specialty, Supermarket Specialty Auto, Department, Mail Order, Specialty Department, Specialty Convenience, Hypermarket, Supermarket, Superstore Department, Discount, Specialty, Supermarket, Superstore DIY Convenience, Department, Hypermarket, Specialty, Supermarket Department, Specialty, Supermarket 46. Loblaws (Canada) (63) Cash & Carry, Convenience, Hypermarket, Supermarket, Superstore, Warehouse 47. May Department Stores (USA) (41) Department, Specialty 48. TJX Cos. (USA) (68) Discount 16,600 5.6% 16,045 5.6% 15,854 11.9% 15,739e 10.2% 15,264 -0.7% e 3.5% 15,129 14,562 -10.3% 14,522 3.5% 13,686 17.1% 13,498 0.2% 13,441 8.5% 13,343 0.4% 13,328 10.9% 1 (N. Am.) 2 (Pac.) 6 (N. Am., Asia, Eur.) 46 (Af., N. Am., S. Am., Asia, Eur.) 1 (N. Am.) 1 (Eur.) 3 (N. Am., Asia) 11 (Asia, Eur.) 2 (Eur.) 27 (N. Am., Asia, Eur.) 1 (N. Am.) 1 (N. Am.) 4 (N. Am., Eur.) 49. McDonald’s (USA) (n.l.) Food Service 50. IKEA (Sweden) (75) Specialty 51. Coop Italia (Italy) (64) 52. Toys “R” Us (USA) (49) 53. Otto Versand (Germany) (26) 54. Meijer (USA) (60) 55. Migros Genossenschaft (Switzerland) (50) 56. Dixons (UK) (98) 57. H.E. Butt (USA) (77) Discount, DIY, Hypermarket, Supermarket Specialty Cash & Carry, Mail Order, Specialty Superstore Convenience, Department, Hypermarket, Specialty, Supermarket, Superstore Specialty Supermarket 58. Coop Norden (Sweden) (n.l.) Convenience, Discount, DIY, Supermarket, Superstore 59. Winn-Dixie (USA) (37) Supermarket 60. SuperValu (USA) (89) Discount, Supermarket, Superstore 61. Kohl’s (USA) (n.l.) Department 12,795 0.6% 12,118 12.5% 11,784e 6.7% 11,566 0.7% 11,419 -10.3% 11,100e 7.9% 10,704 -0.1% 10,702e 15.1% 10,700e 11.4% 10,683 ne 10,633 -5.5% 10,551 15.7% 10,282 22.8% More than 100 (Af., N. Am., C. Am., S. Am., Asia, Eur., Pac.) 32 (N. Am., Asia, Eur., Pac.) 2 (Eur.) 31 (Af., N. Am., Asia, Eur., Pac.) 18 (N. Am., Asia, Eur.) 1 (N. Am.) 3 (Eur.) 13 (Eur.) 2 (N. Am.) 3 (Eur.) 2 (N. Am.) 1 (N. Am.) 1 (N. Am.) 62. Louis Delhaize (France) (n.l.) 63. Uny (Japan) (62) 64. Circuit City (USA) (53) Cash & Carry, Convenience, Discount, Hypermarket, Specialty, Supermarket Convenience, Department, DIY, Drug, Specialty, Supermarket, Superstore Specialty 65. Dell (USA) (n.l.) E-commerce 66. Coop Switzerland (Switzerland) (61) Convenience, Department, Drug, DIY, Food Service, Hypermarket, Mail Order, Specialty, Supermarket 67. Great Universal Stores, PLC (GUS) (UK) (73) 68. Staples (USA) (74) 69. Limited Brands (USA) (55) 70. Millunnium Retailing Group (Japan) (n.l.) 71. Office Depot (USA) (58) 72. Takashimaya (Japan) (56) 73. Yamada Denki (Japan) (n.l.) 74. Systeme U Centrale Nationale SA (France) (54) Department, DIY, Specialty E-commerce, Mail Order, Specialty Specialty Department E-commerce, Mail Order, Specialty Department, Specialty Specialty Hypermarket, Supermarket, Superstore 10,189e 5.1% 10,141 1.0% 9,745 0.9% 9,700e n/a 9,454 2.6% 9,447 6.2% 9,440e 5.8% 8,934 -0.9% 8,546 ne 8,397e -1.4% 8,360 -1.2% 8,330 31.1% 8,264e -2.7% 8 (S. Am., Eur.) 2 (Asia) 1 (N. Am.) Global (ecommerce) 1 (N. Am.) 26 (Af., N. Am., Asia, Eur., Pac.) 10 (N. Am., Eur.) 1 (N. Am.) 1 (Asia) 23 (N. Am., C. Am., Asia, Eur.) 6 (N. Am., Asia, Eur.) 1 (Asia) 4 (Eur.) 75. Empire/Sobey’s (Canada) (72) 76. Wm. Morrison (UK) (n.l.) 77. Seiyu (Japan) (n.l.) 78. Somerfield (UK) (65) 79. Boots (UK) (71) Convenience, Discount, Drug, Supermarket, Superstore Supermarket, Superstore Department, DIY, Specialty, Supermarket, Superstore Convenience, Discount, Supermarket Drug 80. Lotte (S. Korea) (n.l.) Convenience, Department, Food Service, Hypermarket, Supermarket 81. Dillard’s (USA) (59) Department 82. Mercadona (Spain) (n.l.) 83. Army & Air Force (USA) (79) 84. Yum! Brands (USA) (n.l.) Specialty, Exchange Services 85. John Lewis (UK) (88) Department, Hypermarket, Supermarket 86. United Auto Group (USA) (n.l.) 87. CCA Global (USA) (n.l.) 88. Mitsukoshi (Japan) (67) Supermarket Food Service Auto Specialty Department 8,234 12.1% 8,171 14.3% 7,876 -3.1% 7,742 -5.2% 7,649 -0.5% 7,633 12.7% 7,599 -0.5% 7,592 25.2% 7,585 1.3% 7,441 -1.1% 7,437 5.0% e 20.8% 7,000e 23.9% 6,943 -3.5% 7,400 1 (N. Am.) 1 (Eur.) 4 (Asia) 1 (Eur.) 8 (N. Am., Asia, Eur.) 2 (Asia) 1 (N. Am.) 1 (Eur.) Global Global 1 (Eur.) 3 (N. Am., S. Am., Eur.) 5 (N. Am., Eur., Pac.) 10 (N. Am., Asia, Eur.) 89. Dollar General (USA) (n.l.) Discount 90. Kesko (Finland) (100) Auto, Department, DIY, Discount, Food Service, Hypermarket, Supermarket, Specialty 91. Avon (USA) (n.l.) 92. S. Group (Finland) (84) 93. Metcash (South Africa) (n.l.) 94. Hutchison Whampoa/AS Watson (Hong Kong SAR) (n.l.) 95. GJ’s Wholesale Club (USA) (n.l.) 96. Nordstrom (USA) (90) 97. Schlecker (Germany) (96) 98. Galeries Lafayette (France) (83) Direct Selling Cosmetics Auto, Convenience, Department, Discount, Food Service, Hypermarket, Specialty, Supermarket Cash & Carry, Convenience, Specialty, Supermarket Drug, Specialty, Supermarket Warehouse Department, Specialty Drug, DIY, Hypermarket Department, Hypermarket 99. CompUSA (USA) (82) Specialty 100. KESA Electricals (UK) (n.l.) Specialty 6,872 16.4% 6,812 10.7% 6,805 5.5% 6,728 10.1% 6,698e 10.4% 6,631e 31.9% 6,585 13.6% 6,492 5.2% e 6.6% 6,453 6,261 3.7% 4,700e -2.3% 6,233 ne 1 (N. Am.) 5 (Eur.) Global 3 (Eur.) 14 (Af., Asia, Pac.) 15 (Asia, Eur.) 1 (N. Am.) 5 (N. Am., Eur.) 8 (Eur.) 1 (Eur.) 1 (N. Am.) 6 (Eur.) Notes: Source: “2005 Global Powers of Retailing,” Stores, January 2005, available on http://www.stores.org . (i) Continents are abbreviated as follows: Af. = Africa; N. Am. = North America; C. Am. = Central America; S. Am. = South America; Asia = Asia; Eur. = Europe; Pac. = Pacific (Australia, New Zealand). (ii) Target was part of Dayton-Hudson Corporation in 1998. Dayton-Hudson itself was ranked 14th in 1998 sales, and if Target’s 1998 sales are taken alone, it would have ranked 25th in sales in 1998 among global retailers. “n.l.” = not listed in top 100 retailers in 1998. FLOOR MAIN FLOOR (39% of total profit) SECOND FLOOR (12% of total profit) THIRD FLOOR (6% of total profit) FOURTH FLOOR (9% of total profit) FIFTH FLOOR (7% of total profit) SIXTH FLOOR (10% of total profit) SEVENTH FLOOR (9% of total profit) EIGHTH FLOOR (5.5% of total profit) NINTH FLOOR (2.5% of total profit) DEPARTMENT Cosmetics Accessories (belts, handbags, sunglasses) Costume jewelry Fine jewelry Hosiery Men's shirts, ties, accessories Penhaligon's (British shop) Designer sportswear Men's sportswear High-end designer collections Furs Bridal boutique Career wear Designer shoes Women's contemporary designers Shoes Men's suits Men's designer clothing Women's coats Women's petite sizes Women's dresses Lingerie Children's clothes Restaurant & candy shop Salon Z (large sizes) Beauty salon PERCENT OF TOTAL STORE PROFIT GENERATED BY THIS DEPARTMENT 18% 10% 3% 4% 0.5% 3% 0.5% 8% 4% 4.5% 1% 0.5% 8% 1% 6% 1% 8% 2% 3% 4% 2% 3% 2% 0.5% 2% 0.5% Source: adapted from Jennifer Steinhauer (1997), "The Money Department," The New York Times, Magazine Section 6, April 6, pp. 62 Author: Sue Grafton, a popular mystery writer; book titles each start with a letter of the alphabet, beginning with “A is for Alibi,” published in 1982. “R is for Ricochet” was published in 2004. Some of the Sue Grafton books available at www.bookbaron.com on July 5, 2005: Title E is for Evidence Pub. date 1988 Price $125.00 H is for Homicide F is for Fugitive 1991 $50.00 1989 $35.00 I is for Innocent 1992 $35.00 M is for Malice N is for Noose P is for Peril I is for Innocent M is for Malice 1996 1998 2001 1992 1996 $30.00 $30.00 $30.00 $25.00 $15.00 Condition 1st edition; near fine in near fine dust jacket (DJ). Light browning to edges of DJ. 1st edition; near fine in DJ. Signed by author, review copy. 1st edition; fine in near fine DJ; slight yellowing along edge of flaps. 1st edition; near fine in DJ. Inscribed by the author. Light shelfwear, spine lean. 1st edition; fine in DJ. Signed. 1st edition; fine in DJ. Signed. 1st edition; fine in DJ. Signed by author. 1st edition; fine in DJ. 1st edition; near fine in DJ. Light shelfwear. Net Sales ($million) General Merchandise, Hypermarkets, Category Killers: Wal-Mart Home Depot Costco Target Lowe’s Office Supplies, Drugs: Walgreen Best Buy Office Depot Circuit City Department Stores: J.C. Penney May Kohl’s Dillard’s Nordstrom Specialty Stores: Gap Limited Ann Taylor Chico’s SG&A Expenses ($million) SG&A as % of Net Sales 285,222 73,094 47,146 45,682 36,464 51,105 16,504 4,598 9,797 7,562 17.9% 22.6% 9.7% 21.4% 20.7% 37,508 27,433 13,565 10,018 8,072 5,053 3,703 2,308 21.5% 18.4% 27.3% 23.0% 18,424 14,441 11,701 7,529 7,131 5,827 3,021 2,540 2,099 2,020 31.6% 20.9% 21.7% 27.9% 28.3% 16,267 9,408 1,854 1,067 4,296 1,872 843 398 26.4% 19.9% 45.5% 37.3% Source: annual reports for 2004/2005 for each company. Depending on the company’s fiscal year end, 2004 or 2005 figures are used. The actual fiscal years overlap in all cases. RETAILER TYPE Department store (e.g., May Co.) Specialty store (e.g., Gap) Mail Order/ Catalog (e.g., Lands' End) Convenience store (e.g., 7Eleven) Category killer (e.g., Best Buy) Mass Merchandiser (e.g., Wal-Mart) Hypermarket (e.g., Carrefour) Warehouse Club (e.g., Sam's Club) MAIN FOCUS ON MARGIN OR TURNOVER? Margin BULKBREAKING SPATIAL CONVENIENCE WAITING & DELIVERY TIME VARIETY (BREADTH) ASSORTMENT (DEPTH) Yes Moderate Low wait time Broad Margin Yes Moderate Low wait time Narrow Moderate/ Shallow Deep Margin Yes Extremely High Moderate/ High wait time Narrow Moderate Both Yes Very High Low wait time Broad Shallow Turnover Yes Moderate Low wait time Narrow Deep Turnover Yes Low Broad Shallow Turnover Yes Low Broad Moderate Turnover No Low Moderate wait time (may be out of stock) Moderate wait time Moderate/high wait time (may be out of stock) Broad Shallow FIGURE 11-1: U.S. E-COMMERCE SALES, IN $ MILLION AND AS A PERCENTAGE OF TOTAL U.S. RETAIL SALES Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Released May 20, 2005, available at http://www.census.gov/mrts/www.ecomm.htm U.S. E-commerce sales 25,000 2.5 20,000 2 As % of total U.S. sales 1.5 10,000 1 Percent $Million 15,000 E-commerce sales ($million) 5,000 0.5 0 0 1Q05 4Q04 E-commerce as % of total US retail sales 3Q04 E-commerce retail sales ($m) 2Q04 1Q04 4Q03 3Q03 2Q03 1Q03 4Q02 3Q02 2Q02 1Q02 4Q01 3Q01 2Q01 1Q01 4Q00 3Q00 2Q00 1Q00 4Q99 Quarter/Year FIGURE 11-2: PERCENTAGE CHANGE FROM ONE YEAR AGO, IN TOTAL U.S. RETAIL SALES AND U.S. E-COMMERCE SALES Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Released May 20, 2005, available at http://www.census.gov/mrts/www.ecomm.html % Change from 1 Year Ago: Total U.S. Retail Sales and E-Commerce Sales 80 70 60 Percent 50 40 30 20 10 0 1Q 05 $ Change from 1 Year Ago: E-Commerce Sales 04 04 04 04 03 03 03 03 02 02 02 02 01 01 01 01 00 00 00 00 99 % Change from 1 Year Ago: Total U.S. Retail Sales 4Q 3Q 2Q 1Q 4Q 3Q 2Q 1Q 4Q 3Q 2Q 1Q 4Q 3Q 2Q 1Q 4Q 3Q 2Q 1Q 4Q Quarter/Year FIGURE 11-3: PERCENTAGE DISTRIBUTION OF E-COMMERCE SALES BY MERCHANDISE LINE, 2003 (for U.S. Electronic Shopping and Mail-Order Houses) % Distribution of E-Commerce Sales by Merchandise Line, 2003, for U.S. Electronic Shopping and Mail-Order Houses (NAICS 454110), Excluding Nonmerchandise Receipts Total E-Commerce Sales: $37.75 billion; Total Sales: $125.385 billion Other merchandise 13% Toys/hobbies/games 4% Books/magazines 6% Clothing 15% Sporting goods 3% Office equipment/supplies 9% Computer hardware 18% Music/videos 5% Furniture 9% Food/beer/wine 2% Electronics/appliances 8% Computer software 3% Drugs, health/beauty aids 5% E-Commerce as % of Sales for U.S. Electronic Shopping and Mail-Order Houses (NAICS 454110), 2003 Other merchandise Toys/hobbies/games Sporting goods Office equipment/supplies Music/videos Furniture Food/beer/wine Electronics/appliances Drugs, health/beauty aids Computer software Computer hardware Clothing Books/magazines 0.00 10.00 20.00 30.00 Percent 40.00 50.00 60.00 Country Year Retail Sales (in U.S. $) Number of Salespeople Average Sales Per Salesperson Per Capital Income (1998) 1. United States 2003 $29.5 billion 13,300,000 $2,218 $441,400 2. Japan 2003 $27.0 billion 2,000,000 $13,500 $37,180 3. Brazil 2004 $3.92 billion 1,538,945 $2,547 $3,090 4. United Kingdom 2004 $3.03 billion 520,000 $5,827 $33,940 5. Italy 2004 $2.98 billion 272,000 $10,956 $26,120 6. Mexico 2003 $2.89 billion 1,850,000 $1,562 $6,770 7. Germany 2004 $2.88 billion 206,346 $13,957 $30,120 8. Korea 2003 $2.73 billion 3,208,000 $851 $13,980 9. France 2004 $1.72 billion 170,000 $10,117 $30,090 10. Taiwan 2003 $1.56 billion 3,818,000 $409 $25,300* 11. Malaysia 2003 $1.26 billion 4,000,000 $315 $4,650 12. Australia 2004 $1.07 billion 690,000 $1,550 $26,900 13. Canada 2004 $1 billion 898,120 $1,113 $28,390 13. Russia 2004 $1 billion 2,305,318 $434 $3,410 15. Thailand 2004 $880 million 4,100,000 $215 $2,540 16. Venezuela 2000 $681 million 502,000 $1,357 $4,020 17. Argentina 2004 $662 million 683,214 $969 $3,720 18. Poland 2004 $644 million 585,200 $1,100 $6,090 19. Colombia 2004 $583 million 650,000 $897 $2,000 20. Turkey 2004 $539 million 571,799 $943 $3,750 21. India 2004 $533 million 1,300,000 $410 $620 22. Indonesia 2002 $522 million 4,765,353 $110 $1,140 23. Spain 2002 $497 million 132,000 $3,765 $21,210 24. Switzerland 2003 $355 million 6,885 $51,561 $48,230 25. Chile 2004 $338 million 223,000 $1,516 $4,910 Top 10 Direct Selling Countries by Ratio of (Average Sales/Salesperson) to (Per Capita Income) Country 1. Switzerland 2. Brazil 3. India 4. Germany 5. Colombia 6. Italy 7. Japan 8. France 9. Venezuela 10. Chile Ratio of (Ave. Sales per Salesperson) to (Per Capita Income) 1.07 .82 .66 .46 .45 .42 .36 .34 .34 .31 Note: the top table lists the top 20 countries by level of direct sales. The second table lists the top 10 countries ranked by the ratio of sales per direct selling salesperson to per capita income (a value of .66, for example, means that the average direct salesperson makes 66 percent of the average per capita income in that country). Source: Adapted from World Federation of Direct Selling Associations website, http://www.wfdsa.org/, December 1999. Average sales per salesperson are calculated. Per capita income is from the World Development Indicators database of the World Bank, available at http://www.worldbank.org/ . *Taiwan per capita income is reported as gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, purchasing power parity (PPP), for 1998, in The World Factbook 1999, published by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, available at: http://www.odci.gov/cia/publications/factbook/index.html . Source: Anne T. Coughlan and Kent Grayson (1998), "Network marketing organizations: Compensation plans, retail network growth, and profitability," International Journal of Research in Marketing, Vol. 15, p. 403. COMMISSION SCHEDULE: Volume Commission Rate $0-$99 3% $100-$275 5% > $275 7% Janet (personal volume=$2 00) Susan (personal volume=$1 00) Anne (personal volume=$5 0) Catherine (personal volume=$1 00) Lysa (personal volume=$5 0) Kent (personal volume=$1 00) Paulette (personal volume=$5 0) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Off invoice. The purpose of an off-invoice promotion is to discount the product to the dealer for a fixed period of time. It consists of a temporary price cut, and when the time period elapses, the price goes back to its normal level. The specific terms of the discount usually require performance, and the discount lasts for a specified period (e.g., 1 month). Sometimes the trade can buy multiple times and sometimes only once. Bill-back. Bill-backs are similar to off-invoice except that the retailer computes the discount per unit for all units bought during the promotional period and then bills the manufacturer for the units sold and any other promotional allowances that are owed after the promotional period is complete. The advantage from the manufacturer's position is the control it gives and guarantees that the retailer performs as the contract indicates before payment is issued. Generally, retailers do not like bill-backs because of the time and effort required. Free goods. Usually free goods take the form of extra cases at the same price. For example, buy 3 get 1 free is a free-goods offer. Cooperative advertising allowances. Paying for part of the dealers' advertising is called cooperative advertising, which is often abbreviated as co-op advertising. The manufacturer either offers the dealer a fixed dollar amount per unit sold or offers to pay a percentage of the advertising costs. The percentage varies depending on the type of advertising run. If the dealer is prominent in the advertisement, then the manufacturer often pays less, but if the manufacturer is prominent, then he pays more. Display allowances. A display allowance is similar to cooperative advertising allowances. The manufacturer wants the retailer to display a given item when a price promotion is being run. To induce the retailer to do this and to help defray the costs, a display allowance is offered. Display allowances are usually a fixed amount per case, such as 50 cents per case. FIGURE 11-6: DESCRIPTION OF TRADE DEALS FOR CONSUMER NONDURABLE GOODS (CONTINUED) 6. Sales drives. For manufacturers selling through brokers or wholesalers, it is necessary to offer 7. Terms or inventory financing. The manufacturer may not require payment for 90 days, thus increasing 8. Count-recount. Rather than paying retailers on the number of units ordered, the manufacturer does it 9. Slotting allowances. Manufacturers have been paying retailers funds known as slotting allowances to 10. Street money. Manufacturers have begun to pay retailers lump sums to run promotions. The lump sum, incentives. Sales drives are intended to offer the brokers and wholesalers incentives to push the trade deal to the retailer. For every unit sold during the promotional period, the broker and wholesaler receive a percentage or fixed payment per case sold to the retailer. It works as an additional commission for an independent sales organization or additional margin for a wholesaler. the profitability to the retailer who does not need to borrow to finance inventories. on the number of units sold. This is accomplished by determining the number of units on hand at the beginning of the promotional period (count) and then determining the number of units on hand at the end of the period (recount). Then, by tracking orders, the manufacturers know the quantity sold during the promotional period. (This differs from a bill-back because the manufacturer verifies the actual sales in count-recount.) receive space for new products. When a new product is introduced the manufacturer pays the retailer X dollars for a "slot" for the new product. Slotting allowances offer a fixed payment to the retailer for accepting and testing a new product. not per case sold, is based on the amount of support (feature advertising, price reduction, and display space) offered by the retailer. The name comes from the manufacturer's need to offer independent retailers a fixed fund to promote the product because the trade deal goes to the wholesaler. Source: Robert C. Blattberg and Scott A. Neslin (1990), Sales Promotion: Concepts, Methods, and Strategies (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall), pp. 318-319. OBJECTIVES:* TACTICS 1 2 3 4 5 Off invoice x x x x x Bill-back x x x x x Free goods x Cooperative advertising x x Display allowances x x Sales drives x Slotting allowances Street money x x x x x 6 x x *Objectives: Retailer merchandising activities, Loading the retailer, Gaining or maintaining distribution, Obtain price reduction, Competitive tool, Retailer "goodwill." Source: Robert C. Blattberg and Scott A. Neslin (1990), Sales Promotion: Concepts, Methods, and Strategies (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall), p. 321. TABLE 12-1: SOME SOURCES OF INFORMATION ABOUT THE WHOLESALING SECTOR Internet Resources General Industry Information There are many sources of information about wholesale distribution on the Internet. The National Association of WholesalerDistributors operates two web sites: - www.NAW pubs.org – On-line bookstore of NAW reports - www.NAW meetings.org – Upcoming NAW-sponsored events http://www.PembrokeConsulting.com / (A source of forecasts, data, and analyses exclusively on wholesale distribution) TABLE 12-2: PRINCIPAL SERVICES PROVIDED BY MAJOR HARDWARE WHOLESALERSPONSORED VOLUNTARY GROUPS AND WHOLESALER BUYING GROUPS IN THE U.S. Store Identification Merchandising Aid Co-op Advertising Programs Accounting Services Telephone Odering Basic Stock Lists Advertising Planning, Aid Management Consultation Services Microfiche or computerized records of prices & compatible parts numbers Direct-drop Ship Programs Preprinted Order Forms Employee Training Financing Store Planning, Layout Insurance Programs Catalog Service Pool Orders DataProcessing Programs Dealer Meetings Field Supervisor/ Salespeople Private-label Merchandise Consumer Advertising Inventory Control Systems Volume Rebates/ Dividends Dealer Shows Multiple Manufacturers Multiple Manufacturers Master MasterDistributor Distributor Wholesalers Wholesalers 1,250 1,250 (4,000 (4,000branches) branches) Electrical ElectricalContractors Contractors Based on Narayandas, Das and V. Kasturi Rangan (2004), "Building and Sustaining Buyer-Seller Relationships in Mature Industrial Markets," Journal of Marketing, 68 (3), 63-77. TABLE 13-1: SECTORS WITH SUBSTANTIAL FRANCHISE PRESENCE, U.S. AND FRANCE Amusement[i] Automobiles: Rental Service Equipment Business Services Building Products and Services Children’s Products, Including Clothing Cleaning Services and Equipment Educational Services Employment Agencies Health and Beauty (Includes Hair Styling and Cosmetology) Home Furnishings/Equipment Lodging/Hotels Maintenance Miscellaneous Retail Miscellaneous Services, including Training Personal Services and Equipment Pet Services Photography and Video Printing Quick Services Real Estate Restaurants Fast Food Traditional Retail Food Shipping and Packing Travel [i] Categorization adapted from Shane and Foo (1999), already cited, and the French Federation of Franchising website: www.franchise-fff.com TABLE 13-2: THE FRANCHISE CONTRACT The International Franchise Guide of the International Herald Tribune suggests that any franchise contract should address these subjects. Definition of terms Organizational structure Term of initial agreement Term of renewal Causes for termination or non-renewal Territorial exclusivity Intellectual property protection Assignment of responsibilities Ability to sub-franchise Mutual agreement of pro forma cash flows Development schedule and associated penalties Fees: front end, ongoing Currency and remittance restrictions Remedies in case of disagreement[i] [i] Moulton, Susan L.(ed.) (1996), International Franchise Guide, Oakland, California: Source Books Publications. Consider the scenario of a well-established franchisor that has built a network of franchisees. In theory, such a franchisor should be quick to punish transgressions, such as sourcing from a supplier of one’s one choice, rather than suppliers approved by the franchisor failing to maintain the look and ambiance of the premises violating the franchisor’s standards and procedures failing to pay advertising fees--or even the franchisor’s royalty! Such violations happen surprisingly often. When do franchisors exercise their legitimate right to enforce their contracts by punishing the franchisee? Research indicates[i] franchisors weigh the costs and benefits, taking into account the system-investments they need to protect, their own power, and the countervailing power of the franchisee and the franchise network. In particular, in their actions, franchisors appear to consider what signals they are sending to franchisees, both current and potential, by what they tolerate and what they enforce. With this in mind, franchisors pick their battles, rather than enforcing their contracts every time they are violated. When it is particularly costly to enforce, franchisors are more likely to overlook a violation. This is more likely in the following circumstances. The franchisees have a very dense, tightly knit network among themselves. Hence, the franchisor fears a reaction of solidarity, with other franchisees siding with the violator. [i] Antia, Kersi D. and Gary L. Frazier (2001), "The Severity of Contract Enforcement in Interfirm Channel Relationships," Journal of Marketing, 65 (4), 67-81. TABLE 13-3: WHEN DO FRANCHISORS ENFORCE THE FRANCHISE CONTRACT? (CONTINUED) The violator is a central player in the franchisee’s network—with one exception, to be presented below. The franchisor suffers from performance ambiguity, meaning its information systems are not sensitive enough to be sure what is the situation. Such a franchisor cannot monitor well, and therefore cannot be sure its case against the “violator” is strong. The franchisor has built strong relational governance, in which the system operates on norms of solidarity, flexibility, and exchange of information. Such a franchisor doesn’t want to risk ruining these norms—and has other ways to deal with the violation in any case. These are the costs of enforcing the contract. But there are circumstances under which the benefits of enforcement outweigh these costs. The franchisor is more likely to take punitive action to enforce its contract when: The violation is a critical one, such as missing a large royalty payment or operating a very shabby facility in a highly visible location. This is particularly the case when the franchisee is a central player in the network. Ordinarily, central players are protected (as noted above), as the franchisor fears a system backlash. But when a central player violates the contract in a critical way, franchisors choose to enforce because it sends a strong signal that the rules are the rules. Put another way, tolerating a major violation by a central player would signal other franchisees that the contract is just a piece of paper with no real weight. TABLE 13-3: WHEN DO FRANCHISORS ENFORCE THE FRANCHISE CONTRACT? (CONTINUED) When the violator is a master franchisee, that is, with multiple units. Here, the risk is that the violation propagates across this franchisee’s units and become a large-scale problem if the franchisor does not enforce. The franchisor has invested a great deal in the franchise system (as opposed to this particular franchisee). The franchisor needs to protect its investment and the capabilities it has created while building the system. This is true even when the franchisor does enjoy strong relational governance. The franchisor will risk upsetting a given relationship to protect its system investments. When the franchisor is large When there is high mutual dependence in the franchisee-franchisor relationship (so that it can withstand the conflict that enforcement will create) Or when the franchisor is much more powerful than the franchisee (so that the franchisor can coerce the franchisee to tolerate enforcement). Taken together, it is clear that the franchisor weighs the power of both sides and the impact of each act of enforcement on its entire franchise system. Franchisees thus have more power than would appear to be the case if one examines each dyad (franchisor/franchisee) in isolation. FIGURE 13-1: TYPICAL SALES-TO-PROFIT RELATIONSHIPS FOR FRANCHISORS AND FRANCHISEES Adapted from Carmen and Klein (1986) Profits Franchisor Franchisee B* S* Sales FIGURE 14- 1: TYPES OF GOODS FOR SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT Adapted from Fisher (1997) FIGURE 14-2: TWO KINDS OF SUPPLY CHAINS Adapted from Fisher (1997) Physically Efficient Supply Chain (Functional Goods ) _______________ Cut costs of manufacturing , holding inventory , transportation Market-Responsive Supply Chain (Innovative Goods ) ________________ Respond quickly as demand materializes Consequences of Failure Low prices and higher costs create margin squeeze Stockouts of high -margin goods Heavy markdowns of unwanted goods Manufacturing goods Run at high capacity utilization rate Be ready to alter production (quantity and type) swiftly Keep excess production capacity Inventory Minimize everywhere Keep buffer stocks of parts and finished goods Lead times Can be long, as demand is predictable Must be short Suppliers should be Low cost Adequate quality Fast, flexible Adequate quality Product design Design for ease of manufacture and to meet performance standards Design in modules to delay final production Objective