Paper-7

advertisement

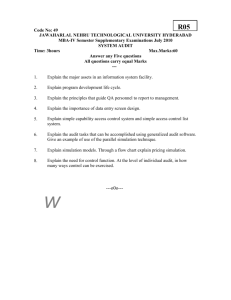

The Relationship between Internal Audit and Information Security: An Exploratory Investigation ABSTRACT The internal audit and information security functions should work together synergistically: the information security staff designs, implements, and operates various procedures and technologies to protect the organization’s information resources, and internal audit provides periodic feedback concerning effectiveness of those activities along with suggestions for improvement. Anecdotal reports in the professional literature, however, suggest that the two functions do not always have a harmonious relationship. This paper presents the first stage of a research program designed to investigate the nature of the relationship between the information security and internal audit functions. It reports the results of a series of semi-structured interviews with both internal auditors and information systems professionals. We develop an exploratory model of the factors that influence the nature of the relationship between the internal audit and information security functions, describe the potential benefits organizations can derive from that relationship, and present propositions to guide future research. Keywords: Internal audit, information systems security, security behaviors 1 The Relationship between Internal Audit and Information Security: An Exploratory Investigation INTRODUCTION Information security is necessary not only to protect an organization’s resources, but also to ensure the reliability of its financial statements and other managerial reports (AICPA 2008). Consequently, COBIT (ITGI 2007), a normative framework for control and governance of information technology, stresses that it is a component of management’s governance responsibilities to design and implement a cost-effective information security program. As a result, IS researchers have begun to investigate various dimensions of information security governance. One stream of research has focused on measuring the value of investments in information security (Bodin et al. 2005, 2008; Cavusoglu et al. 2004a; Gordon and Loeb 2002; Gordon et al. 2003; Iheagwara 2004; Kumar et al. 2008). A second stream of research has examined stock market reactions to disclosures of information security initiatives (Gordon et al. 2010) and incidents (Campbell et al. 2003; Cavusoglu et al. 2004b; Ito et al. 2010). A third stream of research has examined ways to improve end user compliance with an organization’s information security policies (Bulgurcu et al. 2010; D’Arcy et al. 2009; Johnston and Warkentin 2010; Siponen and Vance 2010; Spears and Barki 2010). Little attention, however, has been paid to the operational aspects of information security governance (Dhillon et al. 2007). Indeed, in their review of prior IS research on information systems security governance, Mishra and Dhillon (2006, 20) conclude that the “role of human actors and issues relating to management of people in the organization is not emphasized in popular definitions of information systems security governance.” In particular, they note that the 2 view of information systems security governance used in prior research “does not allow incorporating the importance of the audit process of systems and management of security details at operational level of business process” (Mishra and Dhillon 2006, 21). In addition, a recent web-survey conducted by the Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) recommends a partnership approach between internal audit and IT operations to improve returns on IT control activity investments (Phelps and Milne 2008). This lack of attention to the operational dimension of information security governance in general and the relationship between the internal audit and information security functions is surprising, given the emphasis placed on it in the normative literature. For example, COBIT specifically prescribes that management should “establish and maintain an optimal co-ordination, communication and liaison structure between the IT function and … the corporate compliance group” (PO4.15). In addition, “the control environment should be based on a culture that … encourages cross-divisional co-operation and teamwork …” (PO6.1). Furthermore, it is important to “obtain independent assurance (internal or external) about the conformance of IT with … the organisation’s policies, standards, and procedures …” (ME 4.7). In most organizations, both the information systems and internal audit functions are involved with information security. The IS function has primary responsibility for designing, implementing, and maintaining a cost-effective information security program. Internal audit provides an independent review and analysis of the organization’s information security initiatives. Ideally, the feedback provided by internal audit can be used to improve the overall effectiveness of the organization’s information security. These two functions should work together synergistically to maximize the effectiveness of an organization’s information systems security program. Indeed, there is evidence that the level of cooperation between the internal 3 audit and information security functions is positively associated with the organization’s level of compliance with the IT-related internal control requirements of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (Wallace et al. 2011). Despite the importance of and the potential value that may be derived from the relationship between internal audit and information security, there has been no empirical research investigating how well the two functions work together. This paper reports the results of a study that takes the first steps to fill this gap in the literature. We conducted a series of semistructured interviews with both internal auditors and information systems security professionals to identify the factors that determine the nature of the relationship between the internal audit and information security functions. The dearth of prior research makes such an exploratory approach appropriate. Like case studies, semi-structured interviews with multiple organizations provide an opportunity to explore an under-researched topic and develop research propositions worthy of further investigation (Yin 2003). The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews prior literature and presents a model of how the internal audit and information security functions can work together to help organizations achieve a cost-effective level of information security. Section 3 describes the structured interview method and provides demographic background about the interviewees and the organizations for which they worked. Section 4 presents the common themes that emerged from the interviews. Section 5 concludes the paper by developing a model of the factors that affect the relationship between the internal audit and information security functions and a set of propositions that can be used to guide further research on this topic. BACKGROUND 4 Organizations employ a variety of tools and procedures to provide a desired level of information security. Accountants and auditors typically categorize controls as being preventive, detective, or corrective in nature (Ratliff et al. 1996). Firewalls, intrusion prevention systems, physical and logical access controls, device configuration, and encryption are widely used methods used to prevent undesirable events. Intrusion detection systems, vulnerability scans, penetration tests, and logs are examples of controls designed to detect potential problems and security incidents. Incident response teams, business continuity management, and patch management systems are commonly used examples of controls designed to correct problems that have been identified. Information systems researchers have developed an alternative way to categorize information security-related controls based on the stage during an attempted information security compromise in which the control is most likely to be effective (Ransbotham and Mitra, 2009). Figure 1 shows Ransbotham and Mitra’s (2009) hypothesized relationships among three categories of information security controls. Configuration controls include using methods such as vulnerability scans and patch management systems to reduce the likelihood that attackers will succeed in identifying weaknesses to exploit. Access controls include tools such as firewalls, intrusion prevention systems, physical access controls, and authentication and authorization procedures to reduce the likelihood of an attacker successfully obtaining unauthorized access to a system. Monitoring controls include documentation and log analysis.1 - Insert Figure 1 about here - Ransbotham and Mitra use the term “audit controls” to refer to this concept. Given our focus on the role of internal audit, we adopt the term “monitoring” controls to avoid confusion. 1 5 According to Ransbotham and Mitra (2009), the three types of information systems security controls differ in their objectives. Configuration controls directly reduce the likelihood of an information security compromise by blocking targeted reconnaissance efforts. Access controls also directly reduce the likelihood of compromise by blocking unauthorized attempts to access the system. In contrast to the other two categories, monitoring controls do not directly reduce the risk of an information security compromise. Instead, monitoring controls indirectly reduce the risk of an incident by improving the effectiveness of the other two categories of controls. For example, proper documentation reduces the risk of overlooking key systems when altering default configurations, employing patches, deploying firewalls, and implementing other types of security controls. Similarly, log analysis can help identify the causes of incidents; such knowledge can then be used to modify existing controls to reduce the risk that a similar attack will succeed in the future. Ransbotham and Mitra focus on the role of the information systems security function in implementing all three types of controls. However, as normative frameworks (e.g., COBIT, COSO, etc.) suggest, the organization’s internal audit function should periodically assess the effectiveness of internal controls, including those related to information systems security. We extend Ransbotham and Mitra’s logic concerning the value of monitoring controls to include such periodic assessments by an independent party (internal audit). As Figure 2 shows, we expect that feedback from internal audit can identify opportunities to improve the effectiveness of all types of information systems controls. For example, the results of a security audit can indicate the actual level of end user compliance with policies. An internal audit can also assess the timeliness of acting on information from security logs and other monitoring systems and 6 identify the percentage of devices whose configurations have been corrected in response to vulnerability scans. - Insert Figure 2 about here – The potential benefits of internal audit’s periodic assessment of information security indicated in Figure 2, however, are not automatic. Indeed, the relationship between internal audit and other functions has often been strained (Dittenhofer et al. 2010; Tucci 2009). One possible reason for the relationship problems between internal audit and information security is that they arise from miscommunications between the two functions that reflect differences in background and knowledge. Indeed, there is considerable evidence that communications problems underlie many of the disagreements that often occur between CFOs and CIOs (CFO Europe Research Services 2008). Differences in department size, culture, resources, and unit management’s attitudes are another potential cause of problems between organizational units (Smith et al. 2010). In publicly-traded companies, the internal audit function reports to the audit committee of the Board of Directors, giving it direct access to top management. In contrast, the information systems security function often does not have a direct reporting relationship to top management but instead usually reports to the head of the IT function (e.g., to the CIO) (Bussey 2011). Thus, it is possible that anecdotal reports of sub-optimality in relationships between the internal audit and information systems security functions may be due to personal or organizational characteristics that affect the quality of communications, or both. In order to explore these possibilities and identify other potential factors that may hinder or advance the development of optimal cooperation between the internal audit and information systems security 7 functions, we conducted a series of semi-structured interviews with both internal auditors and information systems security professionals. RESEARCH METHOD This project represents an initial examination of the factors that influence the nature of the relationship between an organization’s information security and internal audit functions. We conducted a set of structured interviews at four organizations. Appendix A presents the list of questions we asked and the underlying source motivation for each topic. Table 1 provides descriptive demographic information about our sample. All four organizations are in the education industry. We chose to focus on educational institutions for a number of reasons. First, we wanted to explore the relationship between internal audit and information security in an industry for which information security was not such an overarching strategic factor that the information security function was likely to be at high level of maturity. Therefore, we ruled out industries where information security is a dominant concern, such as defense contractors and financial services firms. Second, educational institutions have a diverse user base where both employees (faculty and staff) and customers (students) make substantial use of the entity’s user applications. In addition to a diverse user base, educational institutions have a diverse control structure ranging from centralized to decentralized (Anderson et al. 2010). Thus, educational institutions must address the complex set of information security challenges that arise when access to the corporate network is provided to non-employees. Moreover, one set of employees (faculty) represent a particularly interesting user group because of their high degree of autonomy and independence (Hawkey et al., 2008; Schaffhauser, 2010). Third, educational institutions must comply with a number of different regulatory requirements. All are subject to the privacy-related issues delineated in the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act 8 (FERPA). In addition, because they process financial transactions, they are subject to the provisions of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) and must comply with the private industry PCI-DSS standards for transactions involving credit cards. Finally, educational institutions are continually dealing with changes to their business. For example, as educational technologies evolve, institutions must address security issues involved with delivering course content and maintaining confidential student records online. All of these factors make educational institutions a rich setting in which to begin investigating the nature of the relationship between the information security and internal audit functions. - Insert Table 1 about here - Each interview took place at the interviewee’s work location. Two members of the research team participated in each interview. At Institutions A, B, and D one researcher conducted the interview in person and the second participated through a conference call. At Institution C, two members of the research team were physically present for the interview. Although we used the list of questions in Appendix A to provide structure to the interviews, respondents were allowed to discuss additional issues and topics that they thought important. Interviews lasted from 45 to 90 minutes and were recorded and subsequently transcribed for further analysis. Participants were informed that the purpose of the study was to better understand the relationship between IT security and Internal Audit. Miles and Huberman (1994, 240) recommend creating a matrix to analyze qualitative data because it “… is a creative – yet systematic – task that furthers your understanding of the substance and meaning of your database.” They note that there are numerous ways to construct a 9 matrix and that the choice needs to be guided by the nature of the data collected. In this study, our main interest lay in comparing the relationship between the internal audit and information security functions across organizations. Therefore, we used the columns in our matrix to represent the four institutions where we conducted interviews with the rows representing the questions we asked. Miles and Huberman (1994, 241) identify a number of choices concerning the level and type of data to enter in cells. Because the objective of our study is to identify important differences in perspectives among respondents, we decided that cell entries would be direct quotes from our interviewees. The two members of the research team who did not conduct the interview independently completed the cell entries for that institution. The other two members of the research team who had participated in the interviews at a particular organization then compared the completed matrix to the interview transcripts to verify accuracy. All four members of the research team then jointly discussed the contents of the completed matrix and unanimously agreed that the following themes emerged as common topics across the interviews: 1. The effect of internal auditor characteristics on the relationships between information security and internal audit staff. 2. Top management’s influence on the relationship between information security and internal audit. 3. The outcomes of the relationship between information security and internal audit. INTERVIEW FINDINGS Topic 1: The effect of internal auditor characteristics on the relationships between information security and internal audit staff. 10 The interviews indicated that auditor characteristics affected the nature of the relationship between the internal audit and information systems security functions. Specific factors that were mentioned included the level of technical knowledge possessed by the internal auditor, communication skills, and the auditor’s perception of the role of internal audit vis-à-vis information security. Importance of Auditor’s Technical Knowledge Information systems security professionals and internal auditors both acknowledged that the internal auditor’s level of technical IT-related knowledge had a significant effect on the nature of the relationship between the two functions. We’ve actually been very fortunate to hire a very competent IT internal auditor. Intimately familiar with ITGC [IT General Controls] … came from outside, had done IT auditing in a commercial market space, and brought a lot of resources to bear. That’s been really positive. – CISO, Institution A. “And he’s [the internal auditor] very technical so that’s a big advantage. A lot of auditors that I have worked with in the past aren’t as technical. They know textbook theory ….When [name of internal auditor] goes on vacation, I sure am glad to have him back… A lot of the things that I take for granted that [name of internal auditor] knows, the technical side, not all auditors are created equally.” – information security manager, Institution C. At both institutions A and C, there was at least one internal auditor who possessed a technical certification (e.g., CISA or CISSP) related to information security. In contrast, at Institution B none of the internal audit staff possessed much information systems audit 11 technical expertise. Interestingly, the internal auditor at Institution B admitted that the lack of technical expertise within the internal audit staff limited the depth of interaction with the information security function: I think in an organization that has a little bit of a stronger IT Audit presence, the IT Auditors would be working with the people at a lower level; the ones who are actually carrying out the work. Later in the interview, the internal auditor at Institution B commented again on the department’s lack of technical expertise: But, I think we are going to have to find someone on their staff [information security] that understands audit, that could maybe work with us as a liaison and help us understand IT. And then just dig in and start doing some very basic IT audits and then gain some more specialized knowledge through training… In light of these comments, it is not surprising that the CISO at Institution B perceived internal audit’s focus to be more on compliance than on information security issues: We see them and we have a very good working relationship with internal audit. But their focus is typically auditing business process. You know ‘are things being done right in payroll?’, and ‘Are we handling travel vouchers right?’, and that kind of stuff. That has been more their goal. In summary, it appears that when internal auditors possess detailed technical expertise about information security, they are able to develop deeper relationships with the information systems security function. When internal auditors lack such knowledge, their relationship with information systems security staff is less developed. 12 Communication Skills Communication skills, particularly clarity, were mentioned as being important. For example, the IT auditor at Institution A stated: A good IT Auditor should be able to explain what controls are in-scope, and why, prior to the start of testing. With 99% of my interviewees, this is enough to get them on board and most are very receptive to the controls (emphasis in original)…. So long as they’re clear on what I’m testing and why, they are not defensive. On the other hand, the CITO at Institution D expressed some displeasure with the quality of the outsourced internal audit function’s review of the state of information security at the institution: And one of the challenges the audit did not outright say that we needed a security officer, which is sort of the problem because it would have been more helpful if it had. Organizational structure also appears to affect the quality and frequency of communications. For instance, the internal audit and information systems security functions were physically located near one another at Institution C and the participants reported that they had frequent interactions. In contrast, at Institution B, internal audit reported directly to the Board of Regents and did not have a formal channel to communicate with the information systems function. Auditor Attitude and Perceptions of Audit’s Role Both internal auditors and information systems security professionals mentioned that the internal auditor’s attitude and perception about the role or purpose of auditing was important: “I believe the majority of IT Security staff sees us as collaborators, although that was not always the case. In the past they probably considered IT Auditing as a nuisance, and based on the skill sets they encountered that would be understandable. In the past, 13 if Internal Audit found an issue the department [being audited] might experience the recommendation as an unfunded mandate. Now, internal audit takes stock of the issue and tries to collaborate system-wide to leverage existing resources. For example: going to the President’s office to get a threat and vulnerability scanning application purchased for all of the campuses; or asking the President’s office to develop a centralized scanning operation so that each campus doesn’t have to create redundant operations. - IT auditor at Institution A The information security manager at Institution A expressed a similar view about the collaborative nature of the relationship between information security and internal audit: Exceptionally strong to the point of we’ve just realized we have a codependent relationship. It’s been very positive. As discussed earlier, at Institution B, the CISO indicated that internal audit’s role was primarily to monitor compliance with business process policies: But their focus is typically auditing business process. The internal auditor at Institution B agreed with that assessment: … but I would say Business processes is our main focus. At Institution C, both the internal auditor and the information systems security manager agreed that internal audit’s role was to function as an adviser and consultant, rather than as a policeman looking to write up shortcomings. As a result, there was a great deal of mutual trust: “The trust element is important. … I trust that he’s [IT security] going to tell me … but then he trusts me that I’m [Internal Audit] going to take that information and digest it appropriately. I’m not going to get too excited or I’m 14 not just going to dismiss it…. so there’s that mutual trust factor, which I think is really important. If you’re going to be honest with somebody, you don’t want them to turn around and throw you under the bus. You want them to work with you to fix it. That’s one of the key things is that we are very careful from an audit perspective. We don’t want to throw people under the bus. We want to raise issues and then say “okay, what’s the solution?” … That really emphasizes that partnering and that trust, that we don’t want people to get in trouble, we just want to fix it.” – internal auditor at Institution C “It’s not what I’m familiar with being the traditional IT - audit relationship. We can leverage each other’s expertise and position in the organization to make things happen. A lot of times the IT department will tend to almost hide things from audit because they don’t want to get a black eye and we don’t have that issue here so much…. we have the same goals. … A lot of places that I’ve seen and been, it’s been a game of cat and mouse. The auditors are trying to catch IT doing something, IT is trying to prevent audit from finding out…. It’s not the case here… I trust that he’s [Internal Audit] not out to catch anybody doing anything. He’s out to identify and reduce risk.” – Information systems security manager, Institution C In contrast, the CISO at Institution D perceived the relationship with internal audit as being more formal and detached, because it was outsourced to a Big 4 accounting firm: Now, it was an internal audit, but our internal auditors are [name of Big 4 public accounting firm], so they are actually external. 15 In summary, when internal audit perceives its role to be more of an advisor instead of a policeman, mutual trust between the internal audit and information systems security functions is more likely to develop. In turn, as mutual trust between the two functions increases, so too does cooperation. Topic 2: Top management’s influence on the relationship between internal audit and information security. The level of top management’s commitment to security is purported to be an important driver of the overall effectiveness of the organization’s information security initiatives (Hawkey, Muldner, & Beznosov, 2008). In each of our interviews, we found that the information security professional and internal auditor with whom we talked thought that top management was supportive of information security in general. However, the following quotes from information security professionals at all three not-for-profit Institutions (A, B, and D) indicated that while they perceived top management to be very supportive of information security in principle, adequate resources for information security were not necessarily forthcoming: “Because of the high degree of campus autonomy, I think we actually have very good resonance with executive management at the campus level...So I’ve actually met with...EMT here, the executive management team...I’ve presented to that group several times. I’ve presented also to the directors, they’re direct reports that oversee a lot of the core business processes. I feel that the last two years, it’s just night and day. We have good resonance; we’re speaking the same language. Folks understand the risks. I don’t think we’ve seen resource allocation necessarily commensurate with the risk, I think that’s the front to really be fighting but at this point I’m on a first 16 name basis with all of those folks on the EMT, they all know me, they’re familiar with me, that’s a huge one there.” – Information Security Manager, Institution A I wouldn’t say that there is any directive [from top management for information security]. I mean obviously just they assume that it’s going to get done. . . .I think there is a supportive attitude of it, especially in concepts and I think that’s true of not only the president, vice presidents, executive vice presidents here and campus deans. In concept I see lots of support. Where we run into problems is in implementation. The kickback there and individuals typically and then a lot of times that will get escalated. Say well maybe we shouldn’t do this. You know you’ll see quite a difference in philosophy when implementing security in the private sector compared to a public university. – CISO, Institution B An internal audit had just been completed that had been launched prior to me coming and after my predecessor had left. . . And the audit was initiated by the CFO and the Provost. Ostensibly, to give me some traction on a number of things. I think there is a little of, you know, “Be careful what you wish for” regret on their part, because as you can imagine, it revealed a boatload of issues. Which, again, as a new CIO I was grateful for, because it did give me traction. I don’t think executive leadership understood quite how costly it would be to fix it, the implications of not fixing those things and the resource allocation. Not simply as a onetime solution, but as an ongoing; as well as, the formalization of policies and practices. . . I think there was the assumption that I would go out buy some applications, install and everything 17 would be fine. And, the awareness that has developed over the last 6 months has been that we first need to make some policy decisions. We need to be able to enforce those policies. We need to be able to define and document business processes. And then the technology, sort of, comes along or is relevant. So, I would say the trend is that prior to me coming here there was zero awareness. There is increasing awareness that is occurring. The behavioral change is glacially slow and so, I see my work right now being to educate at the executive level. – CITO, Institution D So, I think that they [top management] understand [the need to invest in information security] intellectually. Whether they can practically and politically make the allocation decisions, I’m not sure, but time will tell. . . The gap is pretty wide between what people expect and desire and what, at executive level, they can and will resource. But, my job is helping them understand the issues and closing that gap . . . – CITO, Institution D In addition, at Institution B, the internal auditor indicated that top management’s failure to provide sufficient resources is part of the reason that the internal audit function does not possess a deep level of technical knowledge about information systems security: … we did have a staff person in the office that was kind of going down the path of being groomed to be an IT Auditor. Unfortunately, she left to work in Industry and since then, budgetary constraints, resource constraints; that’s been the main reason why we haven’t. You know we have had conversations with the CIO’s office about how we can kind of get this moving, but it’s still, like I said, a fledging effort. I think we know that we can’t afford to get an IT Audit Professional. They would probably want more money than I make as the manager. 18 In contrast, both the information systems security manager and the internal auditor think that top management at Institution C provides significant budgetary support for information security. In addition, they provide explicit incentives for information security, as indicated in these comments by the information security manager. “So that’s one thing that they include on annual goals, a lot of bonuses depend on compliance and passing audits, being in compliance without major findings and deficiencies. It’s got attention from budget. So I’d say the support is there and they embrace it.” – Information systems security manager, Institution C The information security manager goes on to suggest that the threat of sanctions under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (S-OX) may be motivating top management to devote resources towards compliance issues in general and towards security issues specifically. He also indicates that the effects of S-OX on top management’s attitudes go beyond a focus on compliance to enhancing their understanding of the role of information security in supporting operations: “I do owe a lot of that to Sarbanes Oxley and when they see they could be held criminally liable. Say what you will about the regulations they have really helped the IT security realm because in the past audit has always been fairly well understood. The role of an auditor is clear. But information security hasn’t been. It’s always been identified as hacker deterrence and monitoring and logging in that up until recently it stepped outside of the operational, and really outside of the IT realm and more into a business partnership. That’s why I like the role here, it’s evolving outside of traditionally it was just IT security everything in the IT group, how data bits are moving, now it’s more information. It’s evolving to information, and procedures, and business functions, rather than just the technology side of it.” 19 In addition to providing resources, it is interesting to note that both the internal auditor and the information systems security manager at Institution C made comments indicating that top management played a critical role in shaping the nature of the relationship between the two functions: “Our chief auditor and our senior vice president of IT are very much in that partnering mode, they really feel that audit and IT, same thing with our corporate controller, audit and finance, there should be a partnership, and it should not be adversarial. They really try from a very top down approach, to get all the team members to work together, to partner, we are all trying to drive to a good solution and let’s negotiate and work together.” - internal auditor at Institution C “That’s a great point. It’s the relationships. You read about it in trade magazines and you hear about it in seminars and it really is about the relationships and I’ve seen that demonstrated at [Institution C] better than any place I’ve been in the past .The senior executives identify that, they embrace it, they get along well. I don’t see any conflict or territory battles or any of that here. And [name], the executive auditor, he gets along with our VP of IT really well, and they understand, again they don’t just look at one task, they see the whole picture. That’s the most important thing from the workforce point of view. When they see that demonstrated up high, that’s how they follow suit. They watch this, and then they know that’s the expectation and it’s pretty effortless here. People partner and just get along well with the same goal in mind. It shows.” – Information systems security manager, Institution C 20 In summary, although internal auditors and information systems security professionals at all four institutions indicated that they thought that top management was supportive of information security in principle, only at the one for-profit institution was there agreement that top management supplemented their general statements of support with measurable resources and appropriate incentives. Topic 3: The outcomes of the relationship between internal audit and information security. While the other topics provided information about the factors that influenced the relationship between internal audit and information security the interviews also provided some insight into the possible benefits to organizations of the relationship. This is perhaps the most important topic as the possible benefits that accrue to organizations that support the relationships need to be understood. Comments from interviewees at Institutions A and C provide evidence that a close relationship between the internal audit and information security functions can provide organizational benefits. From the perspective of information security, internal audit support can help overcome resistance to implementing stronger security procedures and improve efficiency: … we’ve just realized we have a codependent relationship. It’s been very positive… a real big benefit to us achieving a lot of the goals we have from an information security perspective.... and we are going to begin reinforcing the importance of change control. And more importantly the importance of completed documentation as part of change control for the deployment of new services and we are going to strongly reinforce through internal audit reports… - CISO, Institution A 21 “If I’m just being the IT network police, and I have to get [name of internal auditor] and he goes in there with a suit and says here’s why you don’t want to do this. They usually just put their tail between their legs.” – Information systems security manager, Institution C. “That’s a key point, our chief auditor and the head of IT both have the same partnering mentality… Our chief auditor …. [has] always been very careful to not create an adversarial relationship as an auditor because when you do that’s when people stop sharing information freely and it really slows the process down and makes it very difficult and cumbersome…” – Information systems security manager, Institution C. From the perspective of internal audit, a good relationship with the information security function is perceived to improve risk management: I know all of the Campus ISO’s [information security officers], and some of their support staff. The relationship adds value by ensuring that the IT Audits are taking into account high risk areas, as perceived by the ISO’s. – Internal auditor, Institution A “I think the partnership kind of helps with that escalation [of information security procedures], because internal audit, we report directly to the CEO and so particularly I’ll use the example of data privacy and conducting the data privacy audit. [The information security manager] and I partner together quite heavily... 22 There were several issues that came out of that. That I was able to sit down with [the internal audit director] and brief him on the risks that we were facing as a company, and he was able take that to his one on one with [the chief executive officer], and then in very short order, policies were changed, adjustments were made, because she was informed that hey there is a risk here that we didn’t know about before, here’s what we recommend...we can be an avenue to escalate appropriately while still maintaining independence and obviously trying not to get into any of the politics among different people competing agendas. Again, it does that provide in that partnership an avenue to get attention to something that could potentially be very serious. – internal auditor, Institution C. “I think another attribute that I would think of is the risk concept of both speaking about risks. He [the security manager] thinks of risks from a very technical nature and he understands that component incredibly well, and I come almost from a process prospective. You put those two together and all of a sudden stuff starts popping out. We’ve got this, we’ve got this, we’ve got this, and then when we look at solutions, and it’s the same thing. He’s got the technical expertise, a lot of times I’m bringing in the process side of it, and we can find figure a solution to meet those different types of risks.” – internal auditor, institution C. SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION There exists little empirical information about the nature of the relationship between internal audit and information security. To begin to address that void, we conducted a series of semi-structured interviews with information security professionals and internal auditors. We 23 found evidence that the nature of the relationship between the internal audit and information systems security functions differs across the four institutions we studied. At Institutions A and C, the two functions appear to have a strong, positive relationship that provides specific benefits to both parties. In contrast, at Institutions B and D the two functions do not appear to have a close relationship, and interviewees did not mention any specific benefits from interacting with the other party. Analysis of the interview transcripts identified several important factors that may account for the differences in the level of interaction between the two functions. Figure 3 presents a model of those factors and provides a number of tentative propositions that can be investigated in future research. - Insert Figure 3 about here – The first three propositions reflect comments made by interviewees’ at all four institutions about how characteristics of internal auditors affect the quality of the relationship between the internal audit and information systems security functions: Proposition 1: Internal audit’s level of IT knowledge directly affects the quality of the relationship between internal audit and information security. Higher levels of technical IT knowledge result in deeper and more effective relationships between the two functions. Proposition 2: Internal audit’s communications skills directly affect the level of cooperation between internal audit and information security. Clearly defining 24 the scope and purpose of an audit results in more cooperation and increased trust by the information systems security function. Proposition 3: Internal audit’s attitude directly affects the level of cooperation between internal audit and information security. When internal audit has a “partnering” or “process improvement” attitude, there will be a higher level of trust and cooperation between internal audit and security. When internal auditing has a “policeman” attitude, there will be less cooperation. Proposition 4 is based on comments by interviewees at Institution C, who indicated a high level of encouragement by top management for the internal audit and information systems security functions to work together: Proposition 4: Top management influences the nature of the relationships between internal audit and information security staff. Specifically, when the top audit and security executives have a “partnering” attitude the relationship between their staff will be much more collaborative than when the relationship between the executives responsible for each function is less positive. Proposition 5 reflects the evidence in our transcripts that the depth of the relationship between the internal audit and information systems security functions was much higher at Institution C, which was a for-profit entity subject to S-OX, than at the other three institutions which were not directly subject to S-OX: Proposition 5: Organizational characteristic, such as the nature of any regulatory compliance requirements and formal communications channels, 25 affect the nature of the relationship between the internal audit and information systems security functions. Our interview results provide some preliminary indications that internal audit can indeed positively affect information security. This leads to proposition 6: Proposition 6a: A collaborative relationship between the internal audit and information systems security functions increases user compliance with the organization’s information security policies and procedures. Proposition 6b: A collaborative relationship between internal audit and information systems security functions improves the effectiveness of internal audit by directing attention to the highest-risk areas. Nevertheless, although respondents at institutions A and C identified a number of positive benefits from a close, friendly relationship between the internal audit and information systems security functions, to effectively fulfill its function internal audit needs to maintain its independence and objectivity (IIA standard 1100). While we did not find evidence of impaired independence, at some point collaboration and enhanced communication may limit perceived independence. The measurement of impaired independence may be difficult, but the potential organizational benefits from fostering a closer relationship between the internal audit and information systems security functions are likely to follow an inverted-U pattern: too little collaboration may lead to inefficiencies and sub-optimal compliance with enhanced information security initiatives, but too much collaboration may limit internal audit’s effectiveness in performing its role of being an independent monitor of compliance and performance. Our results, however, 26 do suggest that cultivating a non-adversarial relationship is likely to increase the effectiveness of both functions. CONCLUSION Monitoring is an integral component of effective internal control (COSO-ERM, 2004). Thus, it stands to reason that regular monitoring of information security controls can improve the overall effectiveness of an organization’s information security program (Ransbotham and Mitra 2009). Although monitoring of information security controls can, and usually is, done by the information security function, additional benefits may accrue when supplemented with review by internal audit (Wallace et al. 2011). The results of this study, however, suggest that the benefits of such independent feedback depend upon the level of IT knowledge possessed by internal auditors, their perception of their role (i.e., policeman versus trusted advisor), top management support, and organizational characteristics. 27 REFERENCES AICPA and CICA. Trust Services Principles and Criteria. American Institute of Certified Public Accountants and Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants. 2008. Anderson, U.L., Christ, M.H., Johnstone, K.M., and Rittenberg, L. Effective sizing of internal audit activities for colleges and universities. The Institute of Internal Auditors Research Foundation, 2010. Bodin, L. D., Gordon, L. A., and Loeb, M. P.Evaluating information security investments using the analytical hierarchy process. Communications of the ACM 2005;48:79-83. Bodin, L. D., Gordon, L. A., and Loeb, M. P. Information security and risk management. Communications of the ACM 2008;51: 64-68. Bulgurcu, B., Cavusoglu, H., and Benbasat, I. Information security policy compliance: an empirical study of rationality-based beliefs and information security awareness. MIS Quarterly 2010; 34:523-548. Bussey, J. Has time come for more CIOs to start reporting to the top? Wall Street Journal, May 17, 2011 accessed via http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704281504576327510720752684.html Campbell, K., Gordon, L. A., Loeb, M. P., and Zhou, L. The economic cost of publicly announced information security breaches: empirical evidence from the stock market. Journal of Computer Security 2003;11: 431-448. Cavusoglu, H., Mishra, B., and Raghunathan, S. A model for evaluating IT security investments. Communications of the ACM 2004a;47: 87-92. Cavusoglu, H., Mishra, B., and Raghunathan, S. The effect of internet security breach announcements on market value: capital market reactions for breached firms and internet security developers. International Journal of Electronic Commerce 2004b; 9:69-104. CFO Europe Research Services. Are CFOs from mars and CIOs from Venus? Overcoming the perception gap to enhance the finance-IT relationship. CFO Publishing Corporation, London, 2008. Chapin, D. A., and Akridge, S. How can security be measured?” Information Systems Control Journal 2005;2. COSO. Enterprise Risk Management – Integrated Framework: Executive Summary.2004. D’Arcy, J., Hovav, A., and Galletta, D. User awareness of security countermeasures and its impact on information systems misuse: a deterrence approach. Information Systems Research 2009;20: 79-98. Dhillon, G., Tejay, G., and Hong, W. Identifying governance dimensions to evaluate information systems security in organizations. Proceedings of the 40th Hawaii International Conference on Systems Sciences, 2007. Dittenhofer, M.A., Ramamoorti, S., Ziegenfuss, D.E., and Evans, R.L. Behavioral dimensions of internal auditing: a practical guide to professional relationships in internal auditing. The Institute of Internal Auditors Research Foundation, 2010. Gordon, L. A., and Loeb, M. P. The economics of security investment. ACM Transactions on Information and System Security 2002;5: 438-457. Gordon, L. A., Loeb, M. P., and Lucyshyn, W. Information security expenditures and real options: a wait and see approach. Computer Security Journal 2003;XIX: 1-7. 28 Gordon, L. A., Loeb, M. P., and Sohail, T. Market value of voluntary disclosures concerning information security. MIS Quarterly 2010;34: 567-594. Hawkey, K., Muldner, K., and Beznosov, K. Searching for the right fit: balancing IT security management model trade-offs. IEEE Internet Computing 2008; 22-30. Iheagwara, C. The effect of intrusion detection management methods on the return on investment. Computers & Security 2004;23: 213-228. ITGI. COBIT 4.1: Control objectives for information and related technology. IT Governance Institute: Rolling Meadows, IL., 2007. Ito, K., Kagaya, T., and Kim, H. Information security governance to enhance corporate value. NRI Secure Technologies 2010. Johnston, A. C., and Warkentin, M. Fear appeals and information security behaviors: an empirical study. MIS Quarterly 2010;34: 549-566. Kumar, R. L., Park, S., and Subramaniam, C. Understanding the value of countermeasure portfolios in information security. Journal of Management Information Systems 2008; 25: 241-279. Miles, M., & Huberman, M. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded source book (2nd edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1994. Mishra, S., and Dhillon, G. Information systems security governance research: a behavioral perspective in 1st Annual symposium on information assurance, Academic Track of 9th Annual NYS Cyber Security Conference, New York, USA , 18-26, 2006. Phelps, D. and Milne, K. Leveraging IT controls to improve IT operating performance. The Institute of Internal Auditors Research Foundation, 2008. Ransbotham, S., & Mitra, S. Choice and chance: a conceptual model of paths to information security compromise. Information Systems Research 2009; 20: 121-139. Ratliff, R.L., W.A. Wallace, G.E. Sumners, W.G. McFarland, and J.K. Loebbecke. Internal auditing: principles and techniques, 2nd edition. Altamonte Springs: Institute of Internal Auditors, 1996. Schaffhauser, D. The business of a data breach. Retrieved September 3, 2010, from Campus Technology: http://campustechnology.com/articles/2010/09/03/the-business-of-a-databreach.aspx Siponen, M. and Vance, A. Neutralization: new insights into the problem of employee information systems security policy violations. MIS Quarterly 2010;34: 487-502. Smith, S., Winchester, D., Bunker, D., and Jamieson, R. Circuits of power: a study of mandated compliance to an information systems security de jure standard in a government organization. MIS Quarterly 2010;34: 463-486. Spears, J. L., and Barki, H. User participation in information systems security risk management. MIS Quarterly 2010;34: 503-522. Tucci, L. How CISOs can leverage the internal audit process. July 28, 2009, accessed online via http://searchcompliance.techtarget.com/news/1362909/How-CISOs-can-leverage-theinternal-audit-process Wallace, L., Lin, H., and Cefaratti, M. A. Information security and sarbanes-oxley compliance: an exploratory study. Journal of Information Systems 2011; 25: 185-212. Yin, R. K. Case study research design and methods (3rd ed). Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2003. 29 Appendix A. Interview Questions Question 1. What is top management’s attitude toward security? How has it changed over the past several years? 2. Who is in charge of security? a. Title? b. To whom reports? c. %time spent on security? Motivation COBIT PO4.8, PO6.1, and DS5.1 stress importance of treating security at a high level in the organization COSO-ERM Internal Environment: requires management to set a philosophy regarding risk Chapin and Akridge (2005) stress importance of trends when assessing information security effectiveness COBIT PO4.1 discusses reporting relationships COSO-ERM Internal Environment: requires assignment of responsibility and authority COSO-ERM Risk Response: management develops actions to align residual risks with the entity’s risk tolerances 3. Which security/IT frameworks(s), if any, are used? (COBIT, ITIL, COSO, ISO 17799/27001, etc.) COBIT PO6.2 stresses need for frameworks to guide policy; ME2 presupposes existence of an internal control framework 4. Which regulations are most important to you? (SOX, PCI, HIPAA, FISMA, etc.) COBIT ME3 stresses need to comply with external requirements COSO-ERM Event Identification: an entity identifies external events affecting achievement of its objectives 5. IT demographics: a. Number of IT staff (dedicated versus non-dedicated) b. Number of IT staff assigned to security? Trend? c. Percentage of staff with security certifications? COBIT PO7 discusses importance of managing IT talent COSO-ERM Internal Environment: states need for “commitment to competence” 30 d. IT budget (as % of revenues)? Change/trend? e. IT security budget (as % of IT budget)? Change/trend? Actual spending versus budget? 6. How would you characterize the working relationship between the IT security staff and internal audit? Between IT security staff and the rest of IT? COBIT PO4.15 stresses need to foster between security and compliance, among other functions COBIT ME2 Maturity model states that higher levels are characterized by increased IT participation in internal control assessments IIA Sections 2050 and 2110.A2 discuss importance of evaluating IT governance COSO-ERM Information and Communication: states that effective communication flows down, across, and up the entity 7. What is internal audit’s level of IT knowledge? (perhaps use a maturity model: 0-5) – asked this of the information security professional IIA Section 1210.A3 discusses importance of auditors possessing knowledge of IT and controls 8. Audit demographics: a. Size of internal audit b. Percentage certified? Which certifications? c. Internal audit budget (as % of revenues)? Change/trend? d. % of audit budget devoted to IT/IS audit? Change/trend? Wallace et al. (2011) use certifications as coarse measure of knowledge and find relationship between certifications and auditor effectiveness COSO-ERM Internal Environment: states need for “commitment to competence” IIA section 2030 COSO-ERM Monitoring: accomplished through ongoing management activities, separate evaluations, or both 31 Figure 1. Relationships Among Different Types of Information Security Controls (adapted from Ransbotham and Mitra 2009, 131) 32 Figure 2. Potential effect of internal audit on information systems security 33 Figure 3. A model of the antecedents and consequences of a relationship between the internal audit and information systems security functions. Internal Audit’s Level of IT Knowledge P1 Internal Audit’s Attitude (Role Perception) Nature of Relationship between Internal Audit and Information Security P2 P3 P4 P6 Benefits of Collaboration between Internal Audit and Information Security P5 Internal Audit’s Communication Skills Top Management Support Organizational Characteristics 34 Table 1. Descriptive information about interviewed organizations Institution A Institution B Institution C Type Public Public University Private, forUniversity profit University Size 27,000 28,000 19,000 (approximate number of students) Size 1100 1700 1800 (approximate number of faculty) Number of 5 1 11 campuses Size of IT (staff) 200 200 50 Number of IT 3 12 1 staff dedicated to information security Title of security Information Chief Information Security professional Security Security Officer Manager interviewed Manager (CISO) Title of internal IT auditor Internal audit Internal Audit auditor manager Senior Manager interviewed Number of 3 0 2 internal audit staff with IT audit expertise Formal reporting Internal audit Internal audit Information channels and information reports to board of security reports security regents; no formal to CIO; CIO organized by channels of and head of campus and communication internal audit have direct between internal have close contact with audit and personal each other information relationship security Institution D Private University 5600 335 1 50 3 Chief Information Technology Officer (CITO) None – internal audit function outsourced N/A Internal audit is outsourced, so no informal communications between internal audit and information security functions 35