Chapter 12 - Basic Skills Initiative

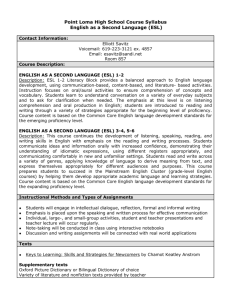

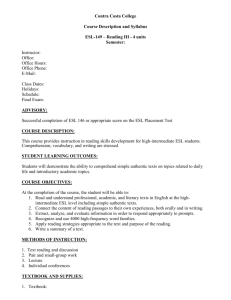

advertisement