FYS Paper Stage Three Essay

advertisement

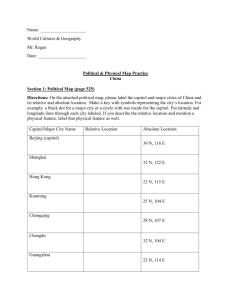

Richmond 1 Elana Richmond Professor Kristin Bezio Dystopia, Revolution, and Leadership December 10, 2012 Falling Birth Rates or Rising Death Rates: An Analysis of my Revision of Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games in the Context of Population Control Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games, already filled with political commentary, is transformed into a specific critique of the dangers of population control through my dystopian rewrite. As I depict in my story, and as has been found true in the implementation of real life programs, population control, although often helpful in achieving short term economic and social goals, creates unrest in the overall population. In The Hunger Games, the people of Panem grow rebellious under the social oppression of the Capitol. In my rewrite of The Hunger Games, the oppression of the people comes out of a warped attempt by the Capitol at population control. Population control in the real world has taken place through China’s “one-child policy,” which dictates that each family should produce only one offspring, and such actions too have led to social discontent. By changing the context of The Hunger Games, I use my rewrite to create an extreme version of current population control policies, highlighting the negative qualities of population control and their potential for creating a feeling of popular discontent similar to that in China. Though my rewrite follows the same trajectory as the original work, the underlying theme of population control moves the message of the story in a different direction: a critique of the government’s involvement in combatting overpopulation. With population control comes a feeling of inferiority for those who are chosen to be removed from the population. When it is forced, population control creates resentment and unhappiness within a population. Most Richmond 2 significantly, population control causes unbalance between classes, which leads to social instability and unrest. And social unrest is just one step away from rebellion. The need to control the world’s population is a relevant and pressing issue in the modern era, encompassing the historical contexts of both China’s one child policy and the “Death Control” policy that appears in my rewrite. Throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries there has been a continuing increase in population growth. In fact, this rise has been so dramatic that demographers predict a thirty-five percent increase in the world’s population by 2050, with numbers still growing (Ehrlich). Unchecked, such growth could result in overpopulation, which brings with it many problems that threaten the sustainability of civilization. A population of the predicted magnitude puts a strain of natural resources, resulting in economic and ecological destruction, as well as shortages in food and water that quickly lead to starvation (Ehrlich). To prevent overpopulation and its subsequent problems, many intellectuals have argued for the necessity of population control measures, however tyrannical they might be (Zubrin). Tyranny is, in a sense, directly connected to population control. Because population control is a policy that must be implemented by force in order to have an effect, it is applied under totalitarian governments such as the Chinese Communist Party or the fictional Capitol. Population control measures were put into effect by the Chinese government in 1979, at a time during which China alone housed about one quarter of the world’s population and therefore felt immediately threatened by overpopulation (Nakra 134). In order to promote economic development and lessen the competition for resources, China implemented the policy of “one child, one couple,” restricting its population through birth control (Nakra 134). In my rewrite, placed in a modern setting threatened by the same problem of overpopulation, the Capitol implements a population control policy for reasons similar to China’s. The Capitol creates a Richmond 3 program with which “the creation of resources would be balanced and consumption competition would be solved,” believing that population control will assure Panem’s prosperity and survival (Richmond 1). The major difference is that the Capitol’s program, instead of limiting population growth, actually cuts down the current population by killing off members of it. Both of these programs, though effective in lowering the population, are forms of oppression. In China, the government infringes on the people’s freedom to have however many children they want. In my rewrite, the government takes it one step further by infringing on the people’s right to live. By revising The Hunger Games, I take the concept of population control to an extreme in order to emphasize the way in which these policies harm the people whom they are supposed to help. Evolutionary biologist Paul Ehrlich believes that “there are only two ways by which a population can stop increasing: a falling birth rate or rising death rates” (Ehrlich). From this concept sprung the foundation of my idea for my revised version of Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games. In the real world, China chose to decrease its birth rate to stop the population from increasing. In my rewrite, I choose to explore Ehrlich’s alternative, rising death rates, in order to impress upon the reader the evils of population control. The novel The Hunger Games, with its “anti-oppressive government premise,” is itself already a critique of the way in which a government can enflame its own people, and therefore works perfectly as a basis for my own critique on population control (Ward). The Capitol’s manipulative control of its population translates easily to manipulative population control. In both cases, the Capitol is an oppressive force, instituting policies that hurt its people. It is a case of “Empire but no Multitude,” in which the power is in the government rather than in the masses (Fisher 5). The tyrannical nature of the Capitol sets up the government’s policies in a negative light, which enforces the argument I am trying to make in my rewrite. And the Hunger Games themselves, a product of government Richmond 4 policy, are equally unethical. Critic Michael Graham describes the Games as “ridiculously, and unnecessarily cruel,” but this is exactly what makes them a powerful symbol (Graham). The Games and all that they stand for are disturbing and immoral, and therefore to link them with any topic is to look upon that topic with a judgmental eye. The Capitol’s tyranny and the cruel nature of the Games, both obviously negative, combine within The Hunger Games to make the ideal foundation for my rewrite. Population control brings into question self-worth, causing a feeling of inferiority among the individuals who are chosen to not remain in the population. This is reflected in the gender imbalance emerging in modern day China and translated to the Reaping ceremony in my rewrite. The feeling of being one “too many,” as Prim refers to her condition in my rewrite, is a real phenomenon associated with population control (Richmond 4). “Son-preference,” the historically prevailing attitude of families in China, due to the fact that sons can provide for the family more than daughters can, has been accentuated by the one-child policy (Milwertz 61). Females are frequently aborted, causing sex ratios to rise to the point where there are now about 120 male births to 100 female births (Nakra 136). Females in China are also often put up for adoption to make room for potential baby boys. These aborted and adopted females are not considered important enough to remain a part of China’s population, like the tributes in my rewrite who are chosen to die. Paul Ehrlich, who argues on the side of population control, believes in the necessity of creating “a world where every child is a wanted child,” but it is population control itself that is causing a spreading feeling of inferiority (Ehrlich 37). In both my rewrite and in China, the victims of population control are those who end up feeling unwanted and unimportant, which is not something that any government policy should make people feel. Richmond 5 In order to emphasize this way in which population control directly damages individuals’ feelings of self-worth, I take the Reaping Ceremony from the original The Hunger Games and put it in a perspective that makes tributes seem more like targets. In the original novel, tributes are chosen from each district at random. Their names are printed on slips of paper, and if an individual’s name is called he or she is forced to participate in the Games unless someone volunteers to take that tribute’s place. Collins names the original reason for the Hunger Games as “punishment for the uprising . . . the Capitol’s way of reminding [the people] how totally [they] are at their mercy” (Collins 18). The Reaping is a blatant show of the Capitol’s power over the population of Panem, with no political agenda other than to instill fear and submissiveness in its people. Fighting in the area becomes a “symbolic act of penance for their past rebellions,” where the chosen tributes are essentially sentenced to death for their forefathers’ actions of dissent (Fisher 1). There is an underlying sense of injustice, for the Games are way for the government to humiliate its own people, but there does not seem to be a feeling of inferiority involved. In the context of population control, however, getting chosen to participate in the Games takes on a new, and more personal, meaning. The purpose of the Games in my rewrite is very specifically to lower Panem’s population, to remove “excess” individuals from the masses. Because of this, there is an emphasis on the concept of tributes as unneeded individuals in the population. As Prim tearfully explains to Katniss, “I’m supposed to die. That’s why my name was called. There are too many people and I’m unnecessary” (Richmond 4). Prim’s logic, however horrifying, is directly in line with the Capitol’s population control propaganda. Population control eliminates people from the population, making them feel inferior. Because the Games are a means of population control, to be named a tribute is essentially to be told that you are have no worth as a member of Panem. Therefore, Prim feels as if she is worthless once she Richmond 6 has been chosen to participate in the Games. The Capitol claims that the Games are “simple survival of the fittest”: to it, Prim is just another dispensable member of a poorer district (Richmond 1). In a policy that is designed to remove extra bodies in an overlarge population, being chosen as a tribute causes individuals to feel as if they do not have value. More wide-spread than feelings of inferiority is the general discontent and unrest that emerges from population control. This is currently the feeling in China, and a sentiment that I spread to Panem in my rewrite. When the one-child policy was first put into action in 1979, the program “caused an uproar among the population and ignited strong resistance” (Feng 2). The Chinese people were not content to have their lives controlled by the government, and so they took action. My rewrite follows similar lines by adhering to the original plot of The Hunger Games, for “eventually, that population will begin to rebel” against the controlling government, due to an overwhelming sense of unhappiness brought about by population control (Richmond 2). Though compliance in China has improved over time, population control is still a source of unhappiness. As Cecilia Milwertz reports, “surveys carried out in both rural and urban areas confirm that the number of children desired continues to exceed policy requirements” (Milwertz 11). These survey results imply that the Chinese people are dissatisfied with, and may even feel persecuted by, the current form family planning policy (Milwertz 11). I try to mirror these feelings of dissatisfaction in my rewrite, “for there is no cheer . . . [and] no shout of applause” during the Reaping ceremony, symbolizing District 12’s opposition to the Capitol’s policies (Richmond 5). The government program of population control conflicts with what the people want, and the people react accordingly. Like China, my version of Panem experiences a popular feeling of unrest in association with population control. Richmond 7 The concept of government action conflicting with the wants of the people is a theme in The Hunger Games, although this sentiment becomes even more widely spread in my rewrite. In Collins’s novel, while many of the districts despise the Capitol for its tyranny, a number of the more affluent districts embrace the Games, or at least seem to. From these districts come “volunteers, the ones who have been fed and trained throughout their lives for this moment” (Collins 94). These tributes, called Careers, are fighting for more than their own survival: they are fighting for honor and glory. Winning the Hunger Games is actually valued in these wealthier districts, as if the Games are a positive thing. In the original Games, the victor also receives food and supplies for his district, as well as riches for himself, which gives the districts another incentive to support their tributes. When the stakes of the Games change, though, fewer people are satisfied with their existence. My rewrite states in the new rules of the Games that “[t]he winner wins nothing but his own life: the promise to never have to compete in the Games again” (Richmond 2). With this change, the purpose of the Games becomes purely to decrease the population. The district as a whole no longer benefits from a victory, and therefore more people are unhappy with the Capitol’s form of population control. To continue this point, Katniss says, “Though I do not know much about the other districts, I cannot believe that any of them [agree with the Capitol’s policy]” (Richmond 5). Her estimate reveals the wide spread nature of the population’s unhappiness with population control. She then asks, “How can you support a policy that is essentially murder?” (Richmond 5). Though this is obviously an exaggeration of the effects of population control, as most real world forms of population control do not include killing, I wanted to emphasize the idea that forced government action in dealing with overpopulation conflicts with what the majority wants. My rewrite removes any redeeming qualities of the Richmond 8 Games, focusing on the idea that manipulating the size of a population by force will lead to mass dissatisfaction with government policy. The effect of population control that threatens to have the largest visible impact, and therefore a stronger push toward potential rebellion, is social instability. In China, observance of the one-child policy dictates the size of social classes. While China’s population as a whole has decreased in line with government policy, adherence to the program has been mostly limited to urban areas, where the government can enforce its authority most directly (Milwertz 58). This unequal enforcement of population control is reflected in my rewrite, in which I have different numbers of tributes for lower and upper class districts. As a consequence of unbalanced enforcement, urban Chinese families are often forced to have only one child, while in more rural parts of the country families get away with having at least two (Milwertz 11). Enforcement differences are creating an unbalanced population. Combined with the effects of industrialization, they also have widened the gap between China’s rich and poor “to the extent that these imbalances might cause social instability” (Nakra 137). Income inequality between city-dwellers and the rural poor has pushed many rural workers to leave the country and try their luck in city industry, causing a shift in the social classes (Nakra 137). This migration is, to an extent, rendering the work of population control obsolete, since it is creating the sort of social competition that population control was supposed to keep in check. Because it is not enforced evenly across classes, population control in China is problematic. Therefore, in my rewrite, I make the enforcement of population control purposefully imbalanced, emphasizing the impossibility of a “perfect” form of population control and thus the inevitability of its causing tension among the people. Richmond 9 Though conflict between the districts does exist to a certain degree in the original novel, adding the element of population control in my rewrite tips the social scale in the direction of, as Nakra puts it, “social instability” (Nakra 137). In The Hunger Games, the Games turn districts against each other. As enemies within the Games, the tributes of each district literally fight each other, which certainly creates social tension between the districts as wholes. In addition, the districts hate the Capitol, “the whole rotten lot of [whom seem] despicable,” since the people of the Capitol are lavishly rich, while the people of the districts must labor to serve them (Collins 65). While the Games do promote tension, though, they do not upset the caste balance: each district has its own “principal industry” that is necessary to the Capitol and so all of the districts are kept as they are (Collins 66). This caste balance becomes tested in my rewrite, however, in which the Capitol decides the importance of each district through by the number of people that it lets live. With Death Control, the government purposely kills off more people in the poorer districts than the wealthier ones. The Capitol uses population control to “cut . . . down the ‘inferior’ portion of the population,” the lower classes, which creates a situation in which Districts 7-12 will eventually have significantly fewer people than Districts 1-6 (Richmond 5). This is problematic, since, as in the original novel, each district’s industry is still necessary. If the size of the districts shifts, then so does the amount of production of each type of product, an example of a social imbalance creating an economic imbalance. Imbalances like these are an issue associated with population control, since population control is a policy that cannot be enforced equally in all areas. Katniss in my rewrite is right when she says with certainty, “We will be needed,” for she understands that every class of people that population control takes away are essential members of the working population (Richmond 6). With an imbalance of districts comes an imbalance of Richmond 10 resources and consumption, taking the problem of competition practically full circle to the times before the implementation of population control. Population control, instead of fixing the problem, shifts the social balance in a way that creates a new problem, creating social and economic tensions that threaten the stability of society as a whole. As seen in modern-day China and as emphasized in my rewrite of The Hunger Games, population control causes unhappiness and unrest in a population. Robert Zubrin is right in calling programs like population control “cruel, callous, and abusive of human dignity and human rights” (Zubrin). Population control causes individuals to feel inferior, the population to feel dissatisfied, and promotes turbulence among the social classes. In China, the oppressed population has not yet made another attempt at rebellion, but this sort of mass unhappiness has evoked rebellion in the past and very well might again in the future. The purpose of using The Hunger Games as a foundation for my rewrite is to invite that possibility: the districts begin a rebellion in response to the cruelty of the original Games, and so they logically begin a similar rebellion in response to the population control-focused version. A message of The Hunger Games is that manipulation of the people by the government causes suffering and resentment. With a revised setting of population control, the Capitol’s policies cause even more personal and widespread feelings of bitterness, resulting in certain rebellion. In exaggerating the tyrannical nature of population control in my rewrite, I enforce the idea that governmental manipulation of a population creates tension among the people that could easily lead to revolution. Richmond 11 Works Cited Collins, Suzanne. The Hunger Games. New York: Scholastic, 2008. Print. Ehrlich, Paul, and Anne Ehrlich. "Paul Ehrlich: Population, Development And The Poor." New Scientist 203.2727 (2009): 36-37. Academic Search Complete. Web. 21 Sept. 2012. Feng, Wang. “Can China Afford to Continue Its One-Child Policy?” Asia Pacific Issues. East West Center, March. 2005. Web. 18 Oct. 2012. Fisher, Mark. “Precarious Dystopias: The Hunger Games, in Time, and Never Let Me Go.” Film Quarterly , 65(4), 27-33. University of California Press, 2012. Web. 9 Nov. 2012. Graham, Michael. “What IS ‘The Hunger Games?’” The Natural Truth. 96.9 Boston Talks, March. 2012. Web. 27 Nov. 2012. Milwertz, Cecilia Nathansen. Accepting Population Control: Urban Chinese Women and the One-Child Family Policy. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon, 1997. Print. Nakra, Prema. "China's "One-Child" Policy: The Time For Change Is Now!." World Future Review 4.2 (2012): 134-140. Academic Search Complete. Web. 21 Sept. 2012. Ward, William. “The Unseen Message of The Hunger Games.” American Thinker. Oct. 2012. Web. 27 Nov. 2012. Zubrin, Robert. “The Population Control Holocaust.” The New Atlantis. The Center for the Study of Technology and Society, 2012. Web. 27 Nov. 2012. Word Count: 3,206 I pledge that I have neither received nor given any unauthorized assistance during the completion of this work Elana Richmond