Juniors' Debating Competition - English

advertisement

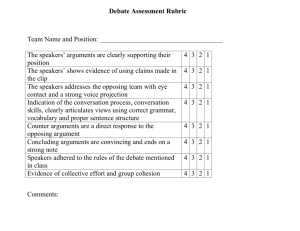

English-Speaking Union Scotland Juniors’ Debating Competition Handbook 1 Contents Page Welcome 3 Competition rules 4 Guidelines for hosts 5 Guidance for speakers 7 Team roles 7 Proposition strategy 8 Opposition strategy 10 Extending a debate 11 General tips: 12 Rebuttal 12 POIs 12 Prioritising 13 Policy or analysis? 13 Expression and delivery 14 Guidance for adjudicators 16 Adjudicator’s Score Sheet 19 2 WELCOME FROM ENGLISH-SPEAKING UNION SCOTLAND The English-Speaking Union (ESU) was founded by Sir Evelyn Wrench in 1918. Today, the ESU is a dynamic educational charity with a presence in more than 50 countries worldwide; ESU Scotland celebrated its sixtieth anniversary in 2012. Any questions about this year’s competition or the other activities of ESU Scotland should be sent via e-mail to: debates@esuscotland.org.uk or by post to: The aims of the ESU have remained the same – to promote the value of effective communication around the globe and to help people realise their potential. English-Speaking Union Scotland 23 Atholl Crescent Edinburgh EH3 8HQ The importance of effective spoken communication skills cannot be underestimated. Even in a global village where communication is dominated by Google, Facebook, Twitter and YouTube (the list goes on), the ability to speak confidently in public remains invaluable for people in all walks of life. World leaders in politics, law, religion, business, science and technology all have an important skill in common. They speak with confidence. or by phone on: 0131 229 1528 Today, ESU Scotland runs a myriad of competitions, workshops and other programmes for people of all ages and backgrounds, which focus on persuasive spoken English. The Juniors’ Competition provides students with an opportunity to develop the vital skills that enable them to speak with confidence in public. Not only does the competition enhance these public speaking and critical thinking skills; it also gives students the opportunity to showcase them in a national competitive arena, which makes the practice of public speaking even more engaging and exciting for everyone involved. 3 COMPETITION RULES Eligibility Conduct of Rounds The ESU Scotland’s Juniors’ Competition is open to schools in Scotland only, unless by specific agreement between a non-Scottish school and ESU Scotland. The use of props or visual aids is not permitted. Amplifying microphones are also not permitted. Microphones may be used for the purpose of recording the debate only. Teams consist of two pupils, both of whom must be in full-time education at the same school, at the time of the competition. The format of the debate, including the role of the chair, the order of speaking and the length of speeches are outlined in this handbook and form part of the competition rules. Entrants into the Juniors’ should be pupils between S1 and S3 inclusive. Speakers may be substituted between rounds, though teachers are advised not to do this unless absolutely necessary. Disqualification Participants who breach the rules relating to registration, eligibility, motions or the conduct of rounds may be disqualified. Should a team containing a substitute speaker progress then in subsequent rounds it must continue in that form and not revert to the original speaker Participants who, in the opinion of the Speech and Debate Officer, act in a manner which would bring themselves or ESU Scotland into disrepute may be disqualified Motions Throughout the competition ESU Scotland will be responsible for setting motions and allocating positions to each school in each debating tie. We will aim to give at least two weeks’ notice to each school in each tie, to ensure that students and teachers have as much time as possible to prepare for the debate. 4 GUIDELINES FOR HOSTS The adjudicators should have an unobstructed view of the speakers. Organising a Round Hosting rounds is not a prerequisite to entry. The competition relies on schools’ hosting so if no school offers to host in a particular area, a school may be asked to host by the competition organisers. Jugs of water, glasses, pens and paper should be placed on all tables. Chair Host schools are responsible for supplying available dates to ESU Scotland, who, in turn, will then send a choice of dates to the other schools in each heat, until a mutually convenient date is set. Debates are usually chaired by a teacher of the host school. The Chair is expected to remain impartial. The Chair is responsible for inviting speakers to deliver their speech and thanking them once they have delivered their speech and maintaining order generally. ESU Scotland will provide the host school with a schedule detailing the list of the participating schools together with a teacher contact point and the team positions in each debating tie Timekeeper A teacher or pupil of the host school usually acts as timekeeper. The timekeeper assists the Chair with the running of the debate and has two functions. ESU Scotland will also be responsible for finding qualified adjudicators for the individual heats. First, the timekeeper is responsible for giving audible signals (usually using a bell or a gavel or by clapping or tapping a glass or the table) indicating when the speaker is in protected or unprotected time and indicating when the speaker’s time is up. Setting up the Room There are number of ways that the room can be prepared for a Juniors’ debate. One option is that three tables should be set up at the front of the room: the centre table is for the chair and the timekeeper, the table on the left (as the adjudicators look at it) is for the proposition teams and the table on the right (as the adjudicators look at it) is for the opposition teams. The first speaker on each team should sit closest to the centre. The adjudicators’ table should be placed at the back of the room or half-way down if the room is large. For all speeches, a single audible signal should be given at the end of protected time (after 1 minute) and at the end of unprotected time (after 4 minutes) At the end of protected time until the end of unprotected time, Points of Information (POI’s) may be offered to the speaker by the opposing side although these do not have to be accepted by the speaker. At the end of the allotted time for the speech (after 5 minutes), a double signal should be given. If the speaker is still speaking at 5 minutes 15 seconds, the timekeeper should give a triple signal and again at 5 minutes 30 seconds, at which point the chair should ask the speaker to conclude their remarks. The layout above is an example; if a more suitable table arrangement fits your available space (and is not creating a bias) please do arrange the tables how you see fit. 5 The timekeeper is also responsible for recording the length of each speech and giving the timings to the judges after the debate. The timekeeper should make a highlighted note of any speaker whose speech was significantly under or over the allotted time. Results The number of regions, the number of heats in each region, the number of schools competing in each heat and the number of schools progressing will change from year to year (depending on the overall number of schools that have entered the competition and their location). Adjudicators ESU Scotland will be responsible for finding adjudicators for the individual heats. ESU Scotland is responsible for ensuring that the adjudicators know how many teams they need to select to progress to the next round. Adjudicators must have experience of school or university debating or some experience of debating, argumentation, mediation, dispute resolution or advocacy from their professional lives. The chair of the judging panel is responsible for informing ESU Scotland which team(s) have been selected to progress to the next round. Ideally, each heat should be judged by three adjudicators. However, it is entirely acceptable and not uncommon for heats to be judged by one or two suitably qualified adjudicators. These must not be connected with any team that is participating in the round. This includes parents, relatives, teachers, coaches, students and other employees of the school. Adjudicators are not required to disclose the individual marks awarded to any team or speaker, but adjudicators should endeavour to give some constructive feedback to all schools and make themselves available to give individual feedback to teams/speakers, if requested. Where there is a tenuous connection which may give rise to bias or the perception of bias (eg an ex-student or ex-teacher), the connection must be disclosed to all teams before the competition and all teams must agree to be adjudicated by the person in question. It is the responsibility of the adjudicator and the host teacher (if they have knowledge of the connection) to ensure that this disclosure is made. At all stages of the competition, the adjudicators’ decision is final. 6 GUIDANCE FOR SPEAKERS Team roles All teams in a debate have to persuade. All speakers, barring the summary speakers, are expected to deliver new arguments in support of their team case. In addition to this, there are specific roles which each team, and individual, must fulfil. Oppositions often start by establishing the clash in the debate. Where do the two benches disagree? It is possible to oppose the practicalities of a specific policy, the principles which underpin that policy, or both. In debates which require some form of policy implementation, point out practical problems with the suggested implementation of that policy. In debates which boil down to a clash of principles, demonstrate why the proposition’s principles are problematic, and establish principles in opposition to the motion. The opening teams The opening proposition team should set up the debate, outlining what they think it is about and what they feel the key issues at stake are. This involves defining the motion: explaining the way in which the terms in the motion are to be understood in the context of the debate. Some definitions will require specific policies; others will start from a clash of principles. The definition, in whatever form, must be made explicit and clear. A more detailed explanation of definitions may be found later on. It is often possible to develop a case which outlines both practical and principled objections to proposition cases. Oppositions can even suggest alternative courses of action to that which has been presented by the opening proposition team. Both speakers ought to respond to the speech which precedes theirs. The first speaker should deal with any definitional problems, and establish the opposition case. The second speaker should then make any additional responses and deliver the remaining team arguments. The opening proposition Opening proposition should seek to deliver principled, and possibly practical, arguments. The sum of a team’s arguments is referred to as their case. It is the first speaker’s responsibility to outline the definition and introduce the team’s case, before moving on to their arguments. The second speaker should rebut (disagree with) the arguments of the opening opposition speaker as well as bringing in their own material. The closing teams Closing proposition and closing opposition comprise the bottom half of a British Parliamentary debate. These teams must differentiate themselves from their opening teams, whilst being careful not to contradict or disagree with them. The opening opposition In opening opposition the team must listen carefully to the opening proposition speakers and respond to their arguments. Debating in opening opposition requires quick thinking and versatility. It is vital that speakers respond to the actual proposition presented, rather than the one they expected. Rather than examining the bottom half teamby-team, it is more useful to look at the distinctions between the two speakers, which apply to both closing proposition and closing opposition. 7 new ways. Using new arguments, however, is unfair on teams who don’t have a chance to respond. It is also irrelevant to a summary speech. New arguments are not a reflection on the debate that happened. New analysis of old material is an effective way of demonstrating the integrity of arguments that were presented. Extension speakers Extension is about differentiation. It is a way of separating the team from the top half of the debate. In this role the speaker must take the debate further, to areas which have not yet been explored, through either new analysis or argument. Proposition strategy Teams in the bottom half are trying to beat not only the opposing teams, but the opening team on their half of the table. Closing teams must follow their opening team’s basic principled stance, but also find a way to show that they are a more effective team in the context of the debate. This is a subtle art, and success can only be achieved through the introduction of some form of new argumentation into the debate. In addition, speakers must also attack the opposing bench, either as a whole, or as two individual teams. Preparation Once the speaker has decided on a topic for the speech and has taken the time to think about all the possible angles or arguments, they should begin researching in more depth. Even where the speaker has prior knowledge of the topic, it is important for them to broaden their perspective as much as possible, and to ensure that the evidence and information they use in their speech is reliable and up-to-date. Summary speakers Speakers should bear the following points in mind when researching their topic: Summary speakers should go into the debate with a blank piece of paper. Their task is to listen to both sides in the debate and deliver a biased summary of the debate that has occurred. Different types of sources Speakers should aim to utilise fact-based resources (e.g. encyclopaedias), academic resources (e.g. journals or reports) and opinion-based resources (e.g. newspapers or news websites). There are a number of different ways in which to frame this. Most summaries take the form of a thematic overview of the debate, looking at the major areas of clash or contention in a debate. This involves bringing together the various elements of the debate and concluding it. Good summaries will reflect the debate which occurred, whilst also suggesting that it was the speaker’s side which had a better grasp and understanding of the key ideas in that debate. Up-to-date information Speakers should ensure that the information they are relying on to support their arguments is up-to-date. The internet is invaluable for checking that the information already obtained (e.g. a journal or newspaper article) is the most up-to-date information available. The summary speakers should spend the debate noting the arguments delivered by both sides. Their speech is an opportunity to demonstrate why, in its key areas of clash, this bench (and team) advanced the most important arguments. In order to do this it is necessary to analyse existing arguments in Multiple sources Speakers should aim, where possible, to have more than one source of evidence, particularly where statistics are involved. It is generally unwise for a speaker to allow one 8 piece of evidence, from one source, to underpin an entire argument in their speech. an identity, you must justify that choice. Will it be a unilateral US invasion? Will it require UN authority? Will it be a multi-party coalition of the willing? You must decide who is going to enact a policy, and why. In defining a motion it is often useful to think of real world proposals. Most motions are set in reference to a real world issue, and as such, proposals often already exist which can shape a debate. For example, in a debate on doing more for the environment you may propose adopting the Kyoto Protocol. Anecdotal evidence Anecdotal evidence (personal stories, myths, memories etc.) is generally unpersuasive, as it usually lacks clarity, certainty and universal applicability. However, depending on the nature of the speech and the style of the speaker, anecdotal evidence can sometimes be used to great effect (particularly if the speaker’s primary goal is to entertain or inspire empathy in the audience; anecdotal evidence can be used to demonstrate the human dimension of an issue). Leaving room for debate Definitions must leave room for debate. One way to look at them is to consider a pyramid. Definitions considered as being far too broad would sit near the base of the pyramid. Conversely, those which have far too much detail and narrow the debate too far would be near the apex of the pyramid. The best definitions are those which sit somewhere near the middle of the pyramid, containing enough detail to be clear, without narrowing the debate unreasonably. Justification You must justify why you want to do what you are proposing. In any debate where a change to the status quo is being proposed, the proposition needs to outline the problem with the status quo. A whole speech may appear irrelevant and inappropriate, if it explains that something can be done without an explanation of why it is necessary. Definitional rules Definition There are a number of things you are not allowed to do in definition. Definition is an explanation of a motion’s key terms in the context of the debate you are going to have. It is not a dictionary definition of every word in the motion. In deciding what to define, it is useful for opening proposition to think in terms of central issues, rather than words. Opening proposition cannot frame the terms of the debate in a way that is unarguable. For example, take the motion, ‘This House believes that France is an irreligious country’. If the proposition define ‘irreligious’ as having no state-sponsored religion this is a truistic definition, as it a simple fact that France has no state-sponsored religion. There may be other ways to analyse the level of religiosity in France that are arguable, and the definition must be open to those ideas. Take, for example, the motion ‘This House supports further expansion of the European Union’. There is no need to define the European Union. Rather, an opening proposition team must outline what is meant by expansion; for example, would they include only Turkey, or incorporate several countries at once? And why? Other motions will require a proposition team to explain who would enact a policy. The motion ‘This House would invade Iran’ requires you as opening proposition to assume the identity of an actor or group of actors. Not only must you adopt Irrelevant definitions (also known, for reasons lost in the mists of time, as squirrels) try to set the debate on a subject different from that expected by the other teams taking part (and the audience). 9 They most often appear when debaters exploit a technical ambiguity in the wording to twist the meaning away from the obvious intention of the motion setter. Turning the motion ‘This House would make voting compulsory’ into a debate about forcing everyone to vote on the X-Factor reality television show is a possible meaning of the words in the motion, but is not what you would expect the debate to be about. structure and the new ideas you are bringing to the debate will be clearer. As well as attacking individual arguments through rebuttal you should have a general theme (or themes) on which to base your criticisms of the proposition. For example, in the debate ‘This House would invade Iran’, you may base your opposition case around the principle of sovereignty. From this principled standpoint you will build individual arguments and target rebuttal, giving the case a sense of unity. Debates must not be unfairly located in a specific region or country, where the participants in the debate cannot be expected to have knowledge of that setting, or where the issues at stake are markedly different from the rest of the world. Alternatively, you may choose a more practical line to take, centring the case around, for example, the idea that invasion in any form will stifle the slowly developing democracy in Iran. Debates must be set up in the present. They cannot be retrospective or set in the future. As an opposition it is useful to think of any proposal from the proposition within the structural framework of: Opposition strategy Being in opposition requires the same basic argumentative and stylistic skills as being on the proposition side, but also involves making strategic choices all of its own. NOW ACTION THEN The proposition will establish a need for the proposal, which is their description of NOW; they will put forward a policy to deal with this problem (ACTION) and describe a world (even if implicitly) where that problem has been solved, or at least mitigated (THEN). Opposing teams, like the proposition, must stand for something, whether it is an implicit support for the status quo, as they object to the implementation of a particular proposal, or an explicit counter-proposal. A stance which objects to both the status quo and the proposition’s proposed change to it, without offering any alternative, is one fraught with problems. Opposing teams can use this model to attack any proposal. Each of the assumptions behind the three elements of the structure may be attacked generically (for example, by claiming that NOW has been misrepresented and is actually not a problem, or THEN will eventually happen anyway without action); and the relationship between multiple elements can be challenged (for example claiming that the ACTION will not lead to the THEN that the proposition has described). Attacking the proposition Most opposition teams will combine a strong attack upon the proposition team, in the form of rebuttal, with the presentation of new arguments in favour of the stance they have chosen, be it a defence of the status quo or an alternative proposal. Constructive arguments and rebuttal may contain much the same kind of content. In opposition you should, in general, try to separate your direct rebuttal from your constructive arguments, because your It is important to remember that not all theoretical attacks on the structure can be applied to every proposition, and that some even contradict each other, so the line (or lines) of attack must be chosen carefully. 10 of argument for your side as you can in the hope that some will have been left out by the first team on their side. Counter-proposals It may be prudent in opposition to offer an alternative proposal. In situations where a defence of the status quo is undesirable, it is possible to concede that there are indeed problems, but to argue that the proposition team’s policy is not the best one to solve the problem. Only after the debate has started can you choose which areas of argument to run yourselves and which have already been sufficiently covered. A good rule of thumb is to narrow a broad debate and to broaden a narrow one. For example, if an opening team has spent their half of the debate focusing on the broad principles which justify a policy, you may analyse case studies demonstrating the policy’s benefits. Conversely, if the opening team spends its time on specifics, you may emphasise the importance of broader principles. This can be done either by making a full counter-proposal, presented in the same way as a proposition policy is, or simply as a suggestion. Hard opposition It is also possible to run what is commonly known as a ‘hard opp’. Hard opps rarely contain any arguments in support of anything; neither the status quo nor any other proposal. Rather, they simply oppose as many elements of the proposition as possible, without adding any constructive material. If you run a hard opp you must bear in mind that, while you may not actively defend it, you are still, by implication, supporting the status quo. Rebuttal Extension speakers also need to spend time on rebuttal. On the proposition bench this is the first opportunity to tackle the second opening opposition speaker and their team case. For closing opposition it means tackling the closing proposition extension speaker. Contradictions Extending a debate Contradicting your opening team is called knifing. Making arguments that cannot logically sit side-by-side with arguments presented by a first team will be heavily penalised by the judges. The jobs you have to do when in closing proposition or closing opposition are very different to those on the top half of the table. It is your responsibility to extend or conclude a debate. Concluding a debate The third speaker on either bench must bring either new analysis or new arguments to the debate. Regardless of how much already seems to have been said on a topic by the first four speakers, there is always scope for the bottom half teams to differentiate themselves from the opening team on the bench. When preparing an extension speech, ask yourself both what areas of argument you can talk about that have not already been covered by the first team on your side, and what issues still need to be won by your side of the debate. Preparation time, when you are a closing team, is not about writing out full speeches but rather thinking of as many areas Summary speeches must draw together the themes that dominated the debate. A summary speaker must listen carefully throughout and continue to prepare their speech up until the moment they start speaking. You should deliver no new arguments (though you can analyse existing arguments in a new way). 11 the speech if your refutation fits into your main arguments, especially in summary. In response to a strong speech, you may need to dedicate more time to demonstrating its flaws. On other occasions, you may decide to keep your rebuttal brief and concentrate on your own case. The decisions you make should be based upon the context of individual debates. General Tips Engagement The need to actively engage with other participants in the debate is what separates debate from other forms of public speaking. In addition to arguing that your team is correct, you must also expose the flaws in opponents’ argumentation. Speakers must also show that they can think on their feet and respond instantly to challenges set by opposing speakers. This engagement occurs in two ways in BP debating: through the rebuttal of opponents’ arguments, and through the giving and receiving of points of information. Points of information Points of information (POIs) can be offered during a speech by any member of the opposing bench. A POI is a chance for a speaker to interrupt opposing speakers’ speeches and ask questions or make brief statements. They can be offered between the first and last minutes of an opposing speaker’s speech. The opening and closing minutes of each speech are protected, and no POIs can be offered during this time. Rebuttal Rebuttal (or refutation) is a vital component of BP debating. It creates engagement between proposition and opposition teams. The time limits on speeches mean that you can rarely rebut everything said by the opposing teams. Effective rebuttal is about selecting the right arguments to refute. It can be tempting to attack the weakest arguments made by an opposing team or highlight something silly they said. However, rebuttal is your opportunity to engage with an opposing team’s key arguments and the crux of their case. When rebutting, you should be looking to dismantle the logic which holds those key arguments, and case, together. You will always gain more credit for attempting to engage with an opposing team’s strongest and most important arguments than for demolishing their weakest, most irrelevant points. A POI must be offered to, and then accepted by, the speaker before it can be asked. It is also important to note that Points of Information should be brief (no longer than 15 seconds). They are not an additional speech, just a short interjection. Giving POIs POIs can shape the flow of the debate, by directing a speaker to discuss those areas of the debate that you think are most advantageous to your team. Those areas may be where you feel you have performed particularly well, or ones which you feel have fallen out of the debate or been ignored by the opposition. POIs can also be used to flag your own arguments. How to do it As a closing team you can force the opening team to spend time on their upcoming material by asking a relevant POI. As an opening team member, later in the debate you can use a POI to draw the judges’ attention to material you delivered earlier. POIs can either be positive (e.g. offering an example or argument for your side) or negative (e.g. highlighting inconsistencies in There are no specific rules on how much rebuttal you should engage in. Many speakers tend to divide their speech between rebuttal and constructive material, beginning with direct attacks on the opposition before moving on to their own material. It is up to individual speakers to decide whether this separation is necessary. It can be effective to merge your rebuttal with the main section of 12 the speaker’s argument or offering a fact which contradicts a speaker’s argument). It is up to you to decide which is most effective in the context of any given debate. them. Finally you should conclude by reminding the audience what you have said. Taking POIs The most important arguments should be given the most time and come earliest in the speech. For example, when proposing a total ban on smoking you may have two arguments to deliver: Prioritising content In a five minute speech you should take one or two POIs. You should also vary who you take POIs from. You will appear weak if you deliberately avoid POIs from the stronger speakers in the debate. • • It is up to you whether you take a POI. The impact a point can have on your speech is determined as much by when you take one as it is by your answer to it. Don’t take POIs midsentence or half-way through a bit of detailed analysis. This will only confuse both you and the audience, and may result in your speech losing flow and impact. It is perfectly acceptable to ask someone offering a POI to stay standing and then accept their point when you have finished the section of the speech you are on (provided you don’t make them wait too long). Smoking kills Cigarette smoke smells bad. While both are perfectly legitimate arguments, it is clear that the first argument is more important than the second. Most choices will not be quite this simple, but it is important to ask yourself in which order arguments should come during your preparation time. Ordering your arguments Some arguments will flow on naturally on from others. Take the example above, ‘This House would ban all smoking’, and the two arguments: Persuasion Debate audiences and judges are not machines, and a speech is not a written essay. Persuasive speeches need to be structured clearly to help the audience to understand their complexities, and they need to be interesting to listeners. • Banning smoking will result in a black market • Smoking is addictive and people will find it hard to give up. The two arguments naturally belong together. If you are trying to argue that a black market in cigarettes will develop, part of your proof of that argument might be to demonstrate the addictive nature of cigarettes. You should keep the arguments together, because having them in separate speeches, or interrupted by another point, would make it harder to appreciate the analytical connection between the two arguments. Structure Separating arguments and presenting them in an orderly manner makes it easier for listeners to appreciate a speech. Clarity of structure is more important in a speech than in a piece of writing because audiences, unlike readers, do not have the ability to go over what was said again if it was unclear. Policy or analysis? You should tell the audience what you are going to say (signpost) at the beginning of your speech, and follow this structure, clearly separating each point as you go through Individual debates differ from each other in terms of the emphasis placed upon policy and analysis. For example, the motion, ‘This House believes Africa’s problems are a legacy of its 13 colonial past’ requires opening proposition to argue for the truth of the statement rather than to propose any specific policy. This, broadly speaking, is an analysis debate. On the other hand, ‘This House would invade Iran’ is a motion which demands a policy by which Iran should be invaded to be presented by opening proposition. This debate would likely focus upon the merits and demerits of a specific, status-quo-altering policy. An analysis debate is essentially the juxtaposition of two things; they can be items, people, states, ideas, or even time periods. Anything that can be compared can be debated about in an analysis debate. Examples of analysis debates include: • This House believes that the media is the West’s greatest weapon in the war on terror • This House believes that we were safer during the Cold War than we are today. It is important to avoid perceiving all debates as falling absolutely into the policy and analysis categories. Many debates will have elements of both. A motion, for example, supporting the remilitarization of Russia could see the presentation of a policy by which Russia would remilitarize as well an analysis of whether a remilitarized Russia was a good thing. The emphasis to be placed upon either policy or analysis can be decided by the team. Expression and delivery Verbal skills Speakers should remember that delivering a speech is not like reading an essay. If the reader of an essay misses a line or misunderstands a phrase, they can go back and re-read it. If a person listening to a speech misses a line or a phrase, they don’t get an opportunity to hear it a second time. It is therefore imperative that speakers speak slowly, clearly and audibly. This will help to ensure that their opponents and the adjudicators hear every word, and can comprehend what is being said. This guide has focused primarily upon policy debates, since they comprise the majority of motions set in BP debate. It is, however, worth considering a suitable approach to analysis motions. An analysis debate asks if the motion is true or false, rather than if the suggestion contained within the motion is a good one or a bad one. Whereas policy motions will contain some kind of directive term, for example ‘would’ or ‘should’, analysis debate motions are worded as statements, for example: ‘This House believes that the United Nations has failed.’ A policy motion on the same issue may be something along the lines of ‘This House would abolish the United Nations.’ Speakers should also attempt to vary their pitch and tone of voice, as well as the pace of their speech (where appropriate). These variations help to keep their listeners alert, and help the speaker to maintain their attention for the full five minutes of the speech. Pauses can also be extremely effective and can be used to emphasise an important point or signal the transition from one section of the speech to another. While proposition teams do not have to explain any kind of policy which they are supporting, they must be sure to define the parameters of the debate. In the example of the UN debate, the opening proposition team would have to attempt to explain what they mean by ‘failed’. Without such parameters being set, there is no field of reference within which the analysis can take place. Non-verbal skills Much of a speaker’s communication is nonverbal. For that reason, public speakers must be conscious of their body language if they are to engage the audience and the adjudicators. 14 ‘Open’ gestures (which help to engage the audience) include facing the audience, and using hands and arms freely to demonstrate, emphasise or otherwise support the words being spoken. By contrast, ‘closed’ gestures (which often disengage the audience) include the speaker folding their arms, facing away from the audience or hanging their head. Linguistic skills Speakers should ensure that their use of vocabulary is consistent (i.e. avoid using multiple words interchangeably to convey the same meaning, as this may lead to confusion). Speakers who have spent a lot of time researching for their speech will probably be very familiar with the surrounding issues, as well as background or ancillary subject matter. However, speakers should bear in mind that many of their listeners will not have their level of specialist knowledge on the issue and should therefore avoid the use of technical, specialist or abbreviated jargon or other unfamiliar terminology (without explanation). 15 GUIDANCE FOR ADJUDICATORS Overview Participants and spectators must be confident in the competence of the adjudicators if they are to accept their decisions and take their advice on board. For that reason, adjudication should be as professional as possible at all stages of the competition. show how their reasons are relevant and link back to their point of view. *The higher mark for the first proposition speaker reflects the particular importance of good content in setting up the basis for a good debate. It should also reward those giving a sensible definition of the motion. Organisation and prioritisation The adjudication panels are normally made up of university students who have competed in public speaking and debating competitions at school and university level, ESU debating competition alumni, accomplished public speakers and communications experts, many of whom use their oratorical and persuasive skills as part of their professional lives. 10 marks for all speeches The speaker should: choose the most important reasons to support their point of view spend more time on the most important reasons, and less time on less important ones. quickly summarise the main reasons to support their view. present their reasons in a clear wellstructured order, with similar reasons grouped together prove easy to follow because they explain the structure of their speech. Marking All speeches receive 40 marks, with the mark distribution for the first proposition* speech being slightly different. 10 marks are awarded for each of the following: Reasoning and evidence Organisation and prioritisation Listening and responding Expression and delivery Listening and responding 5 marks for the first proposition* 10 marks for other speeches The speaker should: listen carefully to other people’s points of view respond to opposing points of view by showing how they disagree ask challenging questions. work with people who share their point of view, by supporting what they have said identify the main disagreements between different speakers and explain who the audience and judges listening should agree with. Reasoning and evidence 15 marks for first proposition* 10 marks for other speeches The speaker should: justify their point of view with several reasons present their reasons simply and clearly in a way the people listening can understand back up their reasons with evidence of different types, including facts, examples and comparisons explain how their evidence supports their reasons *The lower mark for the first proposition speaker is because they have not yet heard an opposing speech and therefore have nothing 16 to rebut. They should, however, show some listening ability through taking and making points of information. flexibility and spontaneity, where this is relevant to their position. A flawed attempt to debate should be marked much more highly than a polished public speech. 3. Teams should be very heavily penalised, and so should not normally progress through to the next stage of the competition, if they: i. offer no points of information ii. accept no points of information (assuming that several were offered to them) iii. make no attempt at rebuttal or refutation, despite the fact that their position at the table makes it important that they do so iv. define the motion in a manner which is very unfair to the opposition teams v. read their speeches vi. are unacceptably abusive towards their opponents vii. have major issues with timing (i.e. out by more than 45 seconds) viii. fail to summarise properly in their summary speech. 4. The judges should know how many teams are due to progress to the next stage of the competition. If there is any doubt about this, the competition organiser should be contacted immediately. 5. One of the adjudicators (normally the presiding judge) should speak briefly before announcing the adjudicators’ decision. The purpose of this speech is to explain the judges’ decision to the audience. With this in mind, this should usually be done by making general remarks about the debate as a whole, rather than offering individual assessments of each speaker. If it is at all possible, the judges are asked please to make themselves available at the end for individual feedback. Expression and delivery 10 marks for all speeches The speaker should: be confident in what they have to say, and not read from notes speak clearly, audibly and slowly be interesting to listen to because they vary the tone and volume of their voice and use pauses use their whole body to support their points through gestures and their facial expression choose their words and the structure of their sentences carefully. Feedback Adjudicators play an integral part in the educational process, by providing constructive feedback to speakers after the competition. Even though adjudication is to a certain extent subjective and intuitive, decisions are more likely to be understood by speakers and coaches if they are justifiable by reference to the objective criteria laid out in this handbook. This also allows speakers to focus on the specific area(s) where there is room for improvement. Adjudicating is also a valuable learning experience for public speaking and debating coaches in particular. It gives them an insight into how their own speakers can be successful from an adjudicator’s point of view. It also hones their skills as coaches and enhances their ability to deconstruct and critique a speech, and give constructive feedback. 1. Judges are not required to fill in the score sheets which are provided. They should, however, be aware of the marking scheme for the Juniors’. 2. Judges should be aware of the role which the speakers were asked to carry out on the table. In particular, reward speakers for showing 17 Adjudicator’s Score Sheet Reasoning / Evidence Organisation / Prioritisation Listening / Responding Expression / Delivery Total 1st Prop Team 1st Prop /15 /10 /5 /10 /40 2nd Prop /10 /10 /10 /10 /40 Team Total /25 /20 /15 /20 /80 1st Opp /10 /10 /10 /10 /40 2nd Opp /10 /10 /10 /10 /40 Team Total /20 /20 /20 /20 /80 3rd Prop /10 /10 /10 /10 /40 4th Prop /10 /10 /10 /10 /40 Team Total /20 /20 /20 /20 /80 3rd Opp /10 /10 /10 /10 /40 4th Opp /10 /10 /10 /10 /40 Team Total /20 /20 /20 /20 /80 1st Opp Team 2nd Prop Team 2nd Opp Team GLOSSARY Speech: A short oral presentation given on a particular motion or resolution. Motion: The subject or issue to be debated, usually beginning with “This House Believes,” “This House Would,” or “This House Supports.” Debate: A formal contest in which the affirmative and negative sides of a motion or resolution are advocated by speakers on opposing sides. Adjudicator/Judge: An observer of a debate who is responsible for deciding which team has won. Where there is more than one adjudicator, they sit as an adjudication panel. Chair: The person who is responsible for introducing speakers, inviting them to the podium to give their speech, inviting them to resume their seat at the end of their speech, ensuring that the rules of the competition are observed and keeping order generally. Timekeeper: The timekeeper assists the chairperson in the running of the debate by timing each speech and providing signals to the speakers indicating how much of their time has elapsed. House: The chamber or auditorium where the debate takes place. Floor: The members of the audience. Proposition/Government/Affirmative: The team that argues in favour of the motion or resolution. Opposition/Negative: The team that argues against the motion or resolution. Point of Information (POI): A formal interjection which may be made during an opposing speaker’s speech. A POI is offered when a speaker stands up and addresses the current speaker saying “on a point of information” or “on that point.” POIs may be accepted or declined by the current speaker. If declined, the speaker offering the POI must resume their seat. If accepted, the speaker offering the POI may make a brief point, after which they must resume their seat and the current speaker continues with their speech. Protected Time: The period of time during which POIs may not be offered, usually the first and last minute of the speech. Unprotected Time: The period of time during which POIs may be offered. Rebuttal/Refutation: The term given to an argument made in direct response to a contrary argument put forward by an opposing speaker. Case: A set of arguments supporting one side of the motion or resolution. Model: The framework of a proposition. Where a motion or resolution requires a proposition team to propose a policy which is contrary to the status quo, the first proposition speaker must specify the parameters within which that policy change will operate. For example, a team proposing the motion “This House Would ban the teaching of religion in schools” would need to specify the jurisdiction within which the ban is proposed to operate, as well as any exclusions or exceptions to the ban. Summary Speech: The final speeches on each side of the debate. Summary speeches should summarise the debate including any floor debate or questions from the audience and should not contain any new material. POIs cannot be offered during summary speeches. Status Quo: The state of affairs which currently exists, the course of action currently pursued or the present system. Manner/Style: The collective term for a range of mechanisms employed by a speaker in the course of a speech including but not limited to emotion, humour, vocabulary, tone of voice and body language. Matter/Content: The substance of a speaker’s case, including the strength of the individual arguments and the extent to which those arguments are supported by empirical evidence, logical analogies and reasoned analysis. Truism: Something which is so obvious or self evidently true that it does not require proof or argument. To define a motion in a truistic way is to effectively make it self-serving and undebatable. Squirrel: Defining a motion in a manner contrary to the spirit of the motion and the intended debate. Both a verb (“he squirrelled that motion”) and a noun (“that definition was a squirrel”), an example of a squirrel would be taking the motion “This House Believes that China should go green” and proposing that China should give the green light and grant independence to Taiwan (thus turning a debate which should have been about environmentalism into a debate about Taiwanese independence).