Miss Julie - University of Warwick

advertisement

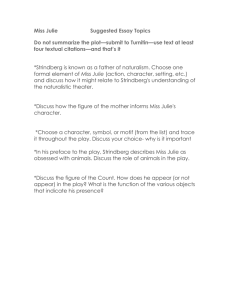

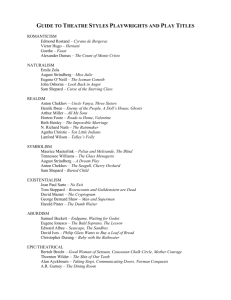

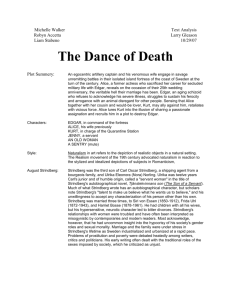

Miss Julie EN302: European Theatre August Strindberg (1849-1912) 1849: born in Stockholm to a shipping agent and a former maidservant. 1856-67: attends a variety of schools (socially diverse upbringing). 1869: briefly studies medicine. 1877: marries the divorced aristocrat Siri von Essen. 1879: first major literary success with his satirical novel The Red Room. 1883-9: lives in France, Switzerland, Germany, and Denmark. 1886: begins his 4-volume novel The Son of a Servant, in which he writes semiautobiographically about himself as the character ‘Johan’. 1887: The Son of a Servant and The Father (among others) 1888: Miss Julie and Creditors (among others). Miss Julie is refused publication and not performed in Sweden until 1904; its performances elsewhere in Europe are initially met with hostility. 1891: divorces Siri von Essen. 1892-1912: far too many interesting things to mention here! Naturalism http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00m7qq1 Darwinism Charles Darwin (1809-82) was a ‘Naturalist’ in the scientific sense of the word. He published The Origin of Species in 1859. Natural selection: those members of a species best adapted to survive in their environment are more likely to reproduce and thereby pass their traits on to the next generation. Darwin encouraged a rational and critical outlook based upon empirical evidence. His theory was shocking and controversial in its challenge to traditional religious beliefs. Émile Zola (1840-1902) French novelist and playwright Influenced by Darwin and the other scientific developments of the century, Zola proposed that literature should reflect the principles of scientific Naturalism: Determinism: all behaviour is determined by genetics and environment. The writer’s task was to depict reality as objectively and as scientifically as possible. ‘Naturalism on the Stage’ Zola published his manifesto on this subject in 1881, in an essay titled ‘Naturalism on the Stage’. He claimed to be reflecting the scientific and rational spirit of the age in which he lived; ‘the impulse of the century,’ he argued, ‘is toward naturalism’ (1881: 5): ‘I am waiting for someone to put a man of flesh and bones on the stage, taken from reality, scientifically analyzed, and described without one lie. … I am waiting for environment to determine the characters and the characters to act according to the logic of facts combined with logic of their own disposition. … I am waiting, finally, until the development of naturalism already achieved in the novel takes over the stage, until the playwrights return to the source of science and modem arts, to the study of nature, to the anatomy of man. (1881: 6) ‘Naturalism on the Stage’ Zola proposed that naturalistic drama should focus on ‘natural man’: ‘…put him in his proper surroundings, and analyze all the physical and social causes which make him what he is… he is a thinking animal, who forms part of nature, and who is subject to the multiple influences of the soil in which he grows and where he lives. That is why a climate, a country, a horizon, are often decisively important.’ (1881: 10) Thérèse Raquin Zola’s first play to explore these ideas was Thérèse Raquin (1873), an adaptation of his 1867 novel. This play examined its characters as ‘human organisms’ – as Zola put it in his Preface, ‘a study in physiology’: Surroundings were described in detail and realistically depicted, emphasising the physiological effects of environment upon characters; Characters are driven primarily by natural urges and instincts – the sexual urge, the instinct of self preservation, the parental instinct (‘Therese and Laurent are human beasts, nothing more.’) The culmination of the play was to be ‘the mathematical solution of the problem posed.’ In contriving a ‘comeuppance’ for Therese and Laurent, however, Zola turns the play into something of a moral fable. Strindberg the naturalist Like Zola, Strindberg saw naturalism as reflective of the scientific age: ‘Nowadays the primitive process of intuition is giving way to reflection, investigation and analysis, and I feel that the theatre, like religion, is on the way to being discarded as a dying form which we lack the necessary conditions to enjoy. … we have not succeeded in adapting the old form to the new content. (1888: 91) During the 1880s, Strindberg wrote that literature ‘ought to emancipate itself from art entirely and become a science’ (1992: 202). Strindberg, it should be noted, had also published academic studies in the fields of anthropology and nature. Strindberg described Miss Julie as ‘the first Naturalistic Tragedy in Swedish Drama’ (1992: 280). Strindberg’s Preface to Miss Julie Michael Robinson argues that ‘the Preface was partly written to convince Zola of [Strindberg’s] naturalist credentials’: ‘Strindberg had sent him a copy of his own French translation of The Father, in the hope that he would promote it, but Zola’s response was lukewarm. Although he praised the play in general terms for its “daring” idea, which is presented to “powerful and disquieting effect”, he found the characterization abstract. According to Zola, Strindberg’s figures lacked “a complete social setting” (un état civil complet).’ (1998: xiii) Determinism in Miss Julie In his Preface, Strindberg describes Miss Julie’s motives as neither ‘purely physiological’ nor ‘exclusively psychological’ (1888: 94): ‘The passionate character of her mother; the upbringing misguidedly inflicted on her by her father; her own character; and the suggestive effect of her fiancé upon her weak and degenerate brain. Also, more immediately, the festive atmosphere of Midsummer Night; her father’s absence; her menstruation; her association with animals; the intoxicating effect of the dance; the midsummer twilight; the powerfully aphrodisiac influence of the flowers; and, finally, the chance that drove these two people together into a private room – plus of course the passion of the sexually inflamed man.’ (1888: 93-4) It is worth thinking about the specificity of the play’s setting: décor, light, symbolism of wider social pressures (e.g. bell, boots). Survival of the fittest Strindberg’s plays often focus on a fight for dominance (or even for survival) which Strindberg characterised as ‘the battle of the brains’: a battle between ‘two implacably hostile minds, bound to each other by desire and hatred’ (Robinson 1998: xi). Survival in Strindberg’s universe is not a matter of morality: ‘The naturalist has abolished guilt with God’ (1888: 96); ‘The servant Jean is the type who founds a species… He has already risen in the world, and is strong enough not to worry about using other people’s shoulders to climb on. … his tendency is to say what is likely to prove to his own advantage rather than what is true.’ (1888: 96-7) Survival of the fittest Strindberg was equivocal about the politics of a Darwinist view of human society: ‘As for the political planner, who wishes to remedy the regrettable fact that the bird of prey eats the dove, and the louse eats the bird of prey, I would ask him: “Why should this state of affairs be remedied?” Life is not so foolishly and mathematically arranged that the great always devour the small. It happens equally often that a bee kills a lion, or at any rate drives it mad.’ (1888: 92) The ‘half-woman’ Strindberg’s view of human nature as a battle between rival ‘types’ for dominance led him to some rather questionable conclusions: ‘The half-woman is a type that pushes herself to the front, nowadays selling herself for power, honours, decorations and diplomas, as formerly she used to for money. She is synonymous with corruption. They are a poor species, for they do not last, but unfortunately they propagate their like by the wretchedness they cause; and degenerate men seem unconsciously to choose their mates from among them, so that their number is increased. They engender an indeterminate sex to whom life is a torture, but fortunately they go under, either because they cannot adapt themselves to reality, or because their repressed instinct breaks out uncontrollably, or because their hopes of attaining equality with men are shattered. It is a tragic type, providing the spectacle of a desperate battle against Nature.’ (1888: 95-6) Photography First photograph taken in 1826 by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce. Englishman William Fox Talbot invented the photo negative in 1835; this enabled photographs to be reproduced. Long exposure times needed for sharp, clear pictures. Technological breakthroughs meant that exposure time was reduced over the 19th century. Early photograph by William Fox Talbot Naturalism and photography Zola on photography: ‘To my mind, you cannot say that you have seen the essence of a thing if you have not taken a photograph of it, revealing a multitude of details which otherwise could not be discerned.’ (Rugg 1997: 83) Darwin appears to have agreed: in 1872, he published The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, with Photographic and Other Illustrations. In this book, Darwin argues that humans and other animals betray their own emotions and read those of others – both consciously and unconsciously – by reading physiological signs. He writes throughout this book about the relationship between exterior signs of emotion, and the body’s nervous, respiratory, and circulatory systems. ‘Expressions of Suffering and Weeping’ (Darwin 1872: pl. 1) Strindberg the photographer Strindberg himself was a keen photographer; around 80 of his photographs survive, many of them at the Strindberg Museum, Stockholm. In 1892, Strindberg planned to open a photographic studio in Berlin; he hoped to take what he called ‘psychological portraits’ of his subjects (or ‘victims’): ‘I have prepared a story for myself … which contains all possible moods. I tell this story to myself while I am exposing the plates and gazing fixedly at the victim. Without suspecting that I am forcing him to do so, only under the influence of my suggestion, he is obliged to react to all the moods I go through in the meantime. And the plate fixes the expression on his face. … In thirty seconds I have captured the whole man!’ (Rugg 1997: 112-113) Is this a Darwinist view of emotion? Strindberg’s self-portraits show him in a variety of roles (author, father, gentleman, musician) – a fractured, unstable ‘self’? Strindberg the photographer Strindberg the photographer Miss Julie in performance, 1906 Modern tragedy Raymond Williams’ Modern Tragedy (1966) analyses some of the ways in which various modern plays might be conceived as having adapted the conventions of classical tragedy. Williams defines tragedy as ‘the conflict between an individual and the forces that destroy him’ (2006: 113). Liberal Tragedy For example, Williams describes Ibsen’s drama as ‘Liberal Tragedy’: ‘…the hero defines an opposing world, full of lies and compromises and dead positions, only to find, as he struggles against it, that as a man he belongs to this world, and has its destructive inheritance in himself.’ (2006: 124) In this view, society is at fault: it is seen as false and oppressive, a trap from which it is impossible to escape. Liberal Tragedy General Gabler’s memory Regional location Oppressive environment Social class / expectations HEDDA GABLER Tesman / identity as ‘wife’ Intellectual boredom Impending motherhood Judge Brack’s ‘leverage’ Threat of scandal Patriarchy Private Tragedy Strindberg’s drama, on the other hand, belongs to a category that Williams calls ‘Private Tragedy’, a form which ‘begins with bare and unaccommodated man’: ‘All primary energy is centred in this isolated creature, who desires and eats and fights alone. Society is at best an arbitrary institution, to prevent this horde of creatures destroying each other. And when these isolated persons meet, in what are called relationships, their exchanges are forms of struggle, inevitably. Tragedy, in this view, is inherent.’ (2006: 133) The association between love and destruction is ‘so deep that it is not, as the liberal writers [like Ibsen] assumed, the product of a particular history: it is, rather, general and natural, in all relationships.’ (2006: 134) Private Tragedy Environment, heredity, body, psyche, etc. Environment, heredity, body, psyche, etc. MISS JULIE JEAN CHRISTINE [Clip from Mike Figgis version, 1999 – track 4] Environment, heredity, body, psyche, etc. Private Tragedy JEAN MISS JULIE Jean’s heredity, body, psyche, etc. are better equipped for survival… A Naturalistic Tragedy? Strindberg himself was ambivalent about Miss Julie’s credentials as a modern tragedy: ‘…the time may come when we shall have become so developed and enlightened that we shall be able to observe with indifference the harsh, cynical and heartless drama that life presents – when we shall have discarded those inferior and unreliable thoughtmechanisms called feelings, which will become superfluous and harmful once our powers of judgment reach maturity. (1888: 92) References Darwin, C. (1955) The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, with Photographic and Other Illustrations, New York: Philosophical Library. Robinson, M. (1998) ‘Introduction’ in Strindberg, A. Miss Julie and Other Plays, Oxford University Press, pp. vii-xxxvi. Rugg, L. H. (1997) Picturing Ourselves: Photography & Autobiography, University of Chicago Press. Strindberg, A. (1888) ‘Preface to Miss Julie’, in Meyer, M. [trans.] (2000) Strindberg, Plays: One, London: Methuen Drama, pp. 91-103. Strindberg, A. (1992) Selected Letters, Volume 1: 1862-1892, ed. M. Robinson, University of Chicago Press. Williams, R. (2006) Modern Tragedy, Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press. Zola, E. (1881) ‘Naturalism on the Stage’, in Cole, T. [ed.] (2001) Playwrights on Playwriting: from Ibsen to Ionesco, New York: Cooper Square Press, pp. 5-14.