THE STRONGER

advertisement

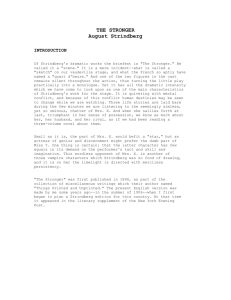

AUGUST STRINDBERG The Stronger Biography of Strindberg The Strindberg Museum The Swedish author August Strindberg (1849-1912) spent the last four years of his life in a building called the Blue Tower. The reconstructed apartment, consisting of three rooms, and his library of some 3,000 works are today the core of the Strindberg Museum. There are also exhibitions presenting various aspects of his life and work. The Young Strindberg - 1875 The Plays of August Strindberg Den fredlöse (first performed 1871, published 1881 The Outlaw, 1912) Mäster Olof (poetic version published 1878, performed 1890; Master Olof, 1915) Lycko-Pers resa (published 1881, performed 1883; Lucky Peter’s Travels, 1930) Fadren (published and performed 1887; The Father, 1899) Kamraterna (published 1888, performed 1905; Comrades, 1912) Fröken Julie (published 1888, performed 1889; Countess Julie, 1912; Miss Julie, 1918) Fordringsägare (first published in Danish trans., 1888; Creditörer, published and performed 1890; Creditors, 1914) Paria (performed 1889, published 1890; Pariah, 1913) Till Damascus (parts 1 and 2 published 1898, performed 1900; part 3 published 1904, performed 1916; To Damascus, 1913) Folkungasagan (published 1899, performed 1901; The Saga of the Folkungs, 1931) Gustav Vasa and Erik XIV (published and performed 1899; Eng. trans. 1931) Påsk (published and performed 1901; Easter, 1912 and 1929) Dödsdansen (published 1901, performed 1905; The Dance of Death, 1912) Kronbruden (published 1902, performed 1906 The Virgin Bride, 1911) Ett Drömspel (published 1902, performed 1907 A Dream Play, 1929) Brända tomten (performed and published 1907 After the Fire, 1913) Spöksonaten (published 1907, performed 1908; The Spook [or Ghost] Sonata, 1916 Stora landsvägen (published 1909, performed 1910; The Great Highway, 1954) Formal portrait Novels. Röda rummet (1879; The Red Room, 1913); Hemsöborna (1887; The People of Hemsö, 1959); I havsbandet (1890; By the Open Sea, 1913). Short stories. Giftas, 2 vol. (1884–85; Married, 1913); Fagervik och skamsund (1902; Fair Haven and Foul Strand, 1913); Sagor (1903; Tales, 1930). Autobiography. Tjänstekvinnans son (1886–87; The Son of a Servant, 1913); Le Plaidoyer d’un fou (first published in French, 1888; enlarged, 1893; The Confession of a Fool, 1912); Inferno (1898; Eng. trans. 1912); Legender (1898; Legends, 1912); Ensam (1903). Translations. There is no English-language edition of the complete works of Strindberg. Individual works are, however, readily available. Recommended modern translations include Twelve Plays by Elizabeth Sprigge (1963); The Plays of Strindberg by Michael Meyer (1964); and the series begun by Walter Johnson in 1955. Siri von Essen - 1882 Frida Uhl Third Wife, Harriet Bosse - 1907 THE STRONGER 'The Stronger' is a two-hander written by August Strindberg in 1889. Two actresses meet in a cafe. Madame X brags about her perfect marriage, patronizing Mademoiselle Y for never having married. The other actress remains silent , and provoked by her silence, Madame X comes to fixate on the idea that her competitor might have had an affair with her husband. Who is the stronger, who is the weaker? What is fact and what is paranoia? The Stronger in performance PART TWO “The Stronger” written by August Strindberg was performed by The Ditsum Players at the Dart Drama festival of 2009. A Considerable Speck On the surface, there’s nothing particularly complicated about Strindberg’s play ‘The Stronger’. Two women – two actresses – run into each other in a restaurant on Christmas Eve. One is married and has been out shopping for presents for her family, the other is unmarried and is sitting alone in the restaurant reading magazines and drinking. We are told almost nothing about these women – they are not even important enough to have names; Strindberg calls them simply Mrs. X and Miss Y. And the entire play (all 6 pages of it) consists of nothing more than a single conversation between these two women. There is no action, no real plot development, nothing particularly out of the ordinary. In fact, one of the women, Miss Y, doesn’t even speak in the entire performance. And yet, in this one simple scene Strindberg creates an episode of incredible, poetic power – a snapshot of life so intense, so powerful, that it rivals Beckett at his best. Like a Kafka short story, ‘The Stronger’ is rich in allegory and lends itself to many layers of interpretation; it is a play that takes little more than ten minutes to read / perform, but that one can easily spend hours thinking about afterwards. It is moreover, a powerful play, one that makes a deep impression, and leaves one with the illusion that one has travelled far and seen much, even though the entire thing is actually incredibly short. What is it that makes the play so powerful? To begin with, it is an immaculate piece of stagecraft. It is a tribute to Strindberg’s genius that despite the fact that Miss Y says nothing right through the play, the interaction between her and Mrs X is in every sense of the term a dialogue. Strindberg uses a combination of stage directions and reactions from Mrs. X to ensure that Miss Y is more than a passive listener and that her responses (or at any rate, Mrs. X’s interpretations of her responses) influence and guide the thread of the scene Second, ‘The Stronger’ is one of those fascinating pieces of writing that lend themselves to multiple (and conflicting) interpretations. As the play progresses, we discover that Miss Y and Mrs. X are rivals for more than theatre roles – Miss Y is having / has had an affair with Mrs. X’s husband. Except that the play never really corroborates this – we only know that by the end of the scene Mrs. X believes that this is true. So the play lends itself to two very different readings: in the first, Mrs. X is an astute wife who discovers the truth about Miss Y and her husband; in the second, Mrs. X is a pathetic and paranoid woman who’s insecurity about her marriage has brought her to slander. This in turn, leaves the question of who is ‘The Stronger’ one (which is, after all, the key to the play) open. Is Miss Y, who chooses to maintain her silence against Mrs X’s accusations (whether false or true) stronger in her independence? Or, as Mrs. X would have it, is she the stronger one, because she has accepted the truth about her husband and found a way to go on? This divergence of interpretation brings us to the first of the allegories implicit in the play – the debate about gender roles. In this simple little episode, Strindberg captures wonderfully the fundamental duality of the role women play in society. In Mrs. X we have the woman as caring mother and devoted wife, a person who has lost all individuality and been completely reshaped by the demands of her husband, a woman who glories in the stability and warmth of the family life she has achieved. On the other hand, we have Y, who is the independent woman, who lives her life her own way and is able, because of her independence to shape others to her personality, but who ultimately ends up alone in a restaurant on Christmas Eve. Obviously these are stereotypes, but Strindberg’s point is precisely to make them stereotypes and set them off against each other, so that what is essentially a quarrel between two women, becomes a larger debate about the role of women in society. What makes this particularly interesting, of course, is that Strindberg is not a writer one associates with sensitive portrayals of women (see for instance, the grotesque caricature that is Miss Julia). But there is, I think, a deeper allegory here. In choosing to silence the character of Miss Y and showing us how Mrs X is able to carry on a conversation (making accusations, drawing inferences) with someone who never actually speaks to her at all, Strindberg has created an image of man’s interaction with God. In the play, Miss Y is not really an individual, but more a sort of human mirror that Mrs X uses to understand and interpret her own life, surfacing her discontent and insecurity and reconciling herself to them by means of a dialogue that is entirely one sided. Miss Y does not need to say anything, and what she thinks or knows has no part in the development of the story. Even the facts are irrelevant here – by the end of the play we do not know what has actually happened, we only know what Mrs. X believes. ‘The Stronger’ is thus a fascinating portrait of both the way individuals can think through the contradictions in their own lives, using another (or the idea of another) as a mere sounding board for their own thought processes, and of the fundamentally conditional nature of truth. The troll in the drawing room Ibsen was sane, progressive and formal. Strindberg was neurotic, reactionary and fragmented. The two were arch enemies - but together they laid the foundations for modern drama, says Michael Billington. (The Guardian, 14 February 2003) Shaw described Ibsen and Strindberg as "the giants of the theatre of our time". Even today we are haunted by their presence, as this year's theatre schedules prove. The two men were not exactly best buddies and still arouse fierce, partisan passions. Henrik Ibsen actually kept a portrait of his arch enemy, August Strindberg, in his study after 1895; he dubbed it "Madness incipient". For his part, Strindberg attacked the "swinery" of A Doll's House and claimed in 1892 that his 10-year war against Ibsen "cost me my wife, children, fortune and career". It is tempting to see the two men as inherently antithetical. On the one hand, Ibsen: sane, progressive, rational, formal. On the other, Strindberg: neurotic, reactionary, religious, fragmented. Michael Meyer, translator and biographer of both,wrote: "Ibsen's characters think and speak logically and consecutively: Strindberg's dart backwards and forwards. They do not think, or speak, ABCDE but AQBZC." I see the two men as violent, necessary opposites, who between them laid the foundations of modern drama. Munch Portrait of Strindberg In his final years