the trial

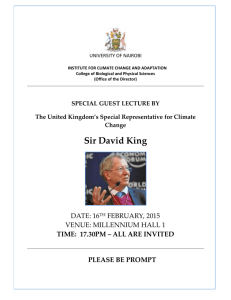

advertisement