Chapter 5: Challenging the Law

advertisement

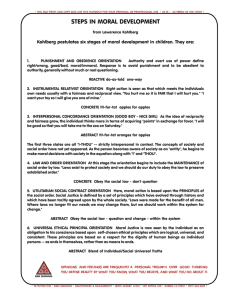

Focus in Our Reading • Remember the 3 commonplaces? [1] Law is a matter of social fact [2] Law is authoritative [3] Law is for the common good Chapter 1: Law must be for the common good Chapter 2: Authority and common good create fundamental legal roles Chapter 3: The Aims of Law Chapter 4: The Aims and Criminal Law Chapter 5: The Aims and Tort Law Chapter 6: Challenges to the 3 Commonplaces Unit 9 and Chapter 6 • This Chapter discusses legal philosophies that challenge the fundamental roles we have studied about our Legal System. [1] Against the Role of Subject: Philosophical Anarchism [2] Against the Role of Legislator: Marxism / Feminist Legal Theory / Critical Race Theory [3] Against the Role of Judge: American Legal Realism Critical Legal Studies Challenging the Law • In order to be non-defective, law must be: [1] genuinely authoritative [2] genuinely for the common good • If these commonplaces are false or misleading, it puts in question the roles of subject, legislator, and judge in paradigmatic [model] legal systems. • Is law genuinely authoritative? • Is it for the common good? Some say NO. Against the Role of Subject • Philosophical anarchism [rebellion] challenges the duty of subjects to obey law. – How can they do that? – Isn’t it self-evident we should obey the law? Maybe not? • There are two ways anarchists challenge the role of subject. [1] Moral duty to be autonomous [2] Moral duty to obey is irrelevant [1] Moral Duty to be Autonomous • Robert Paul Wolff argues: [1] There is a fundamental incompatibility between authority and autonomy, [2] We have a moral duty to be and remain autonomous. • Hence, to be a faithful subject asks too much in terms of sacrifice of one’s autonomy to be a role worth fulfilling. • A response to this argument: [1] Unless the laws are grossly unjust, one should obey because there needs to be a common standard to divide up responsibilities to promote the common good, and [2 ] The law is a good candidate for that standard. The loss of autonomy is justified by the gain for the common good. Loss of Autonomy Is the loss of autonomy justified by the gain for the common good? 1. Do we have a moral duty to be autonomous rather than someone’s slave? 2. Does obedience to law make us a slave, impair our freedom? 3. Does the argument that it benefits the common good really address the question? 4. If we are being compelled to act on behalf of others – what do we gain individually? (2) Is Moral Duty to Obey Irrelevant? • M.B.E. Smith, A. John Simmons, Joseph Raz, and others argue that no theory of moral requirement to obey the law is successful. • Many acts that the law forbids, people would avoid anyway, even if the law were silent, because they are mala in se or wrong in themselves. • Do you agree? • Other acts, which are not mala in se, such as driving on the right side of the road, people would obey because such customs or patterns of coordination exist and it endangers self and others to violate them. • Even if there were no duty to obey law and honor the demands of being a subject, there are other moral requirements that would obtain the same result. Response • There are a number of situations that do not fit into the mala in se patterns. • An important role that law has is regulating the demands we can make on each other, e.g., not to endanger others by driving drunk. • However, your definition of drunk might not be the same as mine. Much of the law is concerned with making more precise these standards of justice. • Can you think of another response? • Do you agree that people would do the right thing anyway even if there were no duty to obey law? Philosophical vs Political Anarchism • Remember that Philosophical Anarchism challenges the duty of subjects to obey law. • Political anarchism is a claim about the undesirability of the state, rather than if one should obey the law. Why is “the State” Undesirable? • Political anarchists’ viewpoints [1] Point out dangers posed by states due to hierarchical structures ruling through coercion, with authority wielded by powerful elites. [2] Argue that the state causes many of the harms it is supposed to remedy. - Example: states divide subjects from each other, oppressing some classes for the benefit of others. [3] This oppression causes crime. However, this anti-state position of political anarchists does not necessarily require an anti-law position. (Distinguish between anti-hierarchy and anti-law) Against the Role of Legislator • Marx claimed that economic features of society generate constraints on noneconomic possibilities within that society. (First we look at economics, then tie that in with law) • Is this true? Do you agree? • Do economics affect values? • Does it determine what is moral and immoral? • Is law designed to keep the rich rich and the poor poor? Other Examples Against the Role of Legislator • Marxists are skeptical about the “science” of economics. They find two notions particularly absurd: [1] The so-called “free market” (it’s not “free”) [2] The so-called “law” of supply and demand (it’s not a law) • Marxists say these notions, masquerading as “science,” are simply myths that serve the interests of capitalism. • To Marxists, the capitalists control both the market (i.e. no way is it free), and also both supply and demand (i.e., there is no neutral “law” of supply and demand). More Examples Against the Role of Legislator • Capitalists clearly control supply, but they also control demand by their control of media, which they use to manipulate people’s perceptions of their “needs.” • Capitalists make people think they need things that they really don’t need. • Having created “demand,” capitalists can raise prices (leaving workers’ wages the same), and make more and more profits. • The condition of the worker inevitably gets worse The more he produces, the less he can buy. Legislation is corrupt • Marx says the economic class to which one belongs determines the concept of morality and value that one adopts. • It is inevitable over the long haul that the results of one class dominating another will be reflected in law itself. • Principles that appear to be neutral on their face will turn out to be favorable to those in power. Why? • This bias could be due to: [a] Those with economic power often have control over making and applying law [b] Lawmakers and judges are drawn from the elite class [c] The legal order is unable to sustain norms too contrary to the prevailing economic relationships. • What do you think? Historical “evidence” • Evidence of this phenomenon is shown as law’s initial response to lawsuits by factory workers against their employers for injuries received on the job. • The defenses of [1] assumption of risk [2] contributory negligence [3] the fellow servant rule were all used by judges to deny recovery. • Even the advent of Worker’s Compensation, which provided an alternative method of recovery, was just a concession that blocked fuller reform as it [1] does not compensate pain and suffering [2] caps damages, allowing employers to pay far less than full compensation for on the job injuries. Why does Worker’s Comp limit damages payable to workers? Remember What Marx and His Followers Say • Rules of property are not neutral but tools by which the wealthy [1]accumulate wealth [2]accumulate power to the disadvantage of those who are poor. • Free speech is not neutral but enables the wealthy to have a louder voice and more influence. • The test of neutrality is not appearance but the real effects. Law Can’t Be for Common Good Because of Class Conflict • Marx’s points: – There is no neutral concept of justice and good – Class status shapes members’ concepts of justice and the common good – There is no genuine long-term prospect that law can be for the common good. – There can be no hope for law that is for the common good until society no longer consists of classes in conflict. • What do you think? Those Who Think Marx Was Only Partly Right • Pluralists accept Marx’s views about power and how that precludes neutrality in law, but reject his view that economics is the ultimate determining ground. • If not economics, then what else could determine allocation of power by law? Feminist Legal Theory • Men hold a dominant position socially and economically • That causes law to be biased in favor of men even when it appears to be neutral on its face • For example, Catherine MacKinnon claims that interpreting freedom of speech to protect pornography undervalues the harm pornography causes to women Critical Race Theory • A similar argument is made by Critical Race Theory regarding hate speech • Both views say that until power relationships based upon gender or race are eliminated, the law will favor the dominant group • Legislators will not be able to genuinely deliberate about the common good. • What do you think? Author’s response • The point about one’s views being determined by class, gender, or race is made too strongly • Legislators are capable of being objectively benevolent. • In other words, they’re exaggerating Against the Role of Judge • Judges take legal rules as a guide in making decisions. • Sometimes the law “runs out” and, it is argued, sometimes judges have to make decisions that go beyond the rules. • This raises two questions: – (1) How pervasive is this phenomenon? – (2) To what extent does this call into question the role of judge? American Legal Realism [Against the Role of Judge] • American Legal Realism says law is massively indeterminate, at least for those cases that are appealed (as contrasted with mundane cases). • This skepticism is founded on the idea that interpretive standards are not sufficient to account for what will be relevant in determining what precedent is or what statutes and other law mean in a particular case. Critical Legal Studies [Against the Role of Judge] The philosophy of Critical legal studies says: • Unlike standard Marxism, it does not hold that the dominant group need be characterized in economic terms. • Offshoots of this approach include: – Feminist legal theory – Critical race studies But aren’t outcomes predictable? • The fact that judges’ decisions are largely predictable cannot be explained by the law’s determinacy but from other facts: – political beliefs – moral beliefs – social factors, such as class • Do you agree? Consequences If realists are right, appellate judges are not making decisions in accordance with their role as judge because they are not applying law. Do you see how this challenges the integrity of the legal system? Critical Legal Studies Go Further • Even in the everyday workings of the lower court the law is filled with indeterminacy • Judges have shared substantive extralegal understandings – moral views – political views – ideas that property understandings can’t be violated • Concluding that “law is politics.” • The critics say judges are lawmakers rather than appliers of law. If They’re Right, Do We Really Need Judges? • If legal indeterminacy is so great, why should subjects accept judicial decisions as authoritative if those decisions are not fixed by law but are the result of judicial discretion? • If cases are not decided based upon technical legal reasoning, but are the result of broader moral and political thinking… • Judges as a class have no more expertise in these areas than other persons. (Should judges should be elected like legislators?) • Response 1: An argument for having judges do this work is: – the practical need for binding decisions resolving disputes – but this raises the question of whether alternative sources of resolution might be better Is judging just politics? Response 2 Response 2: – if cases are decided based upon shared moral and political understandings, perhaps these understandings are genuine truths about human good and are generally shared and easily known. • Do judges reflect our shared moral and political understandings?