Scholars for Peace in the Middle East: Message

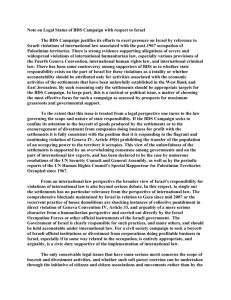

advertisement

Message from the Editor Joel Fishman Editor, Scholars for Peace in the Middle East It has been our policy to offer the reader a generous selection of timely news reports and thought pieces relating directly and indirectly to the cause of peace in the Middle East. This complex subject is does not lend itself to a neat definition or compartmentalization. The reality of politics in the Middle East is a bit like fivedimensional chess. There are several levels. Among these are the facts on the ground, our perceptions, those of others, their bearing on Western values and morality, and a discussion of this interplay in the media, on campuses and in academic fora everywhere. For this reason particularly, the transmission of honest, factual information is a matter of great importance. In addition, the debate about developments in the Middle East and their implications is not confined geographically, but has become the subject of elite academic discourse. We are pleased to provide our readers with original content, including three book reviews as well as one review article. In addition, we have reprinted the article, “Why the Middle East Is the Way It Is,” a contribution of SPME Board member, Philip Carl Salzman. It is our policy to seek original material, and we turn to our readers for submissions and suggestions. We would welcome two types of articles: 1) general academic articles about topics and issues, and; 2) articles with descriptions and analysis of the situation at different campuses. The main issue for this period has been the emergence of the movement for boycott, divestment, and sanctions (BDS) against Israel. Recently, the BDS activities at the University of Pennsylvania during the weekend of February 4 have drawn widespread attention. In the coming weeks another event is scheduled to take place on the campus of Harvard University. This time, the program will advocate the “One-State Solution,” for Israel and the Palestinians. At the same time, the supporters of the Palestinian cause have revived the accusation that Israel is an apartheid state, a stale propaganda slogan which the USSR flogged during the Cold War. The unifying theme of these movements is the assertion that the State of Israel is so devoid of moral virtue that it does not deserve to exist, that it should be delegitimized and subjected to a regime change which would destroy its Jewish character and its truly humane but occasionally imperfect system of government. Needless to say, such accusations lack merit and have been repeatedly disproved. Many accusations against the Jewish state are mendacious, and in this issue of the Faculty Forum, one can learn about a recent court decision in France which thoroughly discredited the assertions of Muhammad al-Dura’s father that he had been wounded and injured by the bullets of Israeli soldiers. The reader can find these articles in Section II, under the heading, “In the Courtroom.” As Jonathan Tobin wrote, “In the latest chapter of the battle over this story that has just been played out in France’s Supreme Court, the Palestinian narrative has suffered another defeat. The court vindicated a doctor who was sued by al-Dura’s father for saying the wounds he claimed to have suffered on the day of his son’s death were not the result of Israeli fire.“ The Muhamad al-Dura affair represented the first blood libel of the Twenty-First Century. It fueled the Second Intifada (The Second Armed Uprising) which resulted in terror and murder in Israel and the spread of anti-Jewish violence abroad, particularly in France. While it is gratifying to see lies disproved and to witness the triumph of the truth, the attitude of the bystanders continues to remain a matter of concern. The dynamic of violence not only includes the perpetrators and victims, but also bystanders who turn the other way, who take refuge in double standards, or give credence to lies. This state of affairs may be found on some American campuses, where university administrators have allowed the freedom of their academic space to be misused – something which has happened before. One need only consult Stephen H. Norwood, The Third Reich in the Ivory Tower: Complicity and Conflict on American Campuses (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009). (Edward Alexander reviewed this title in a past number of the Faculty Forum.) One of the great challenges which SPME is facing is to assure that the bystanders of our time understand and appreciate their great moral responsibility. This is one reason why it is necessary to develop a better knowledge of the real message of the BDS movement and an appreciation of the danger it represents. Pascal Markowicz, a legal advisor on the task force opposing the boycott for the CRIF, the roof organization of French Jewry, wrote, “The boycott is the new battlefield of the media and legal war which has been declared against Israel.” Similarly, a background briefing paper which the CRIF published on the subject of Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions, the BDS initiative, cites the judgment of the European Court of the Rights of Man of July 16, 2009, that the boycott of a French mayor against Israeli food products in the municipal cafeteria represented “incitement to an act of discrimination.”[1] This decision is significant because it links the act of boycotting to incitement and discrimination, indicating a part of the dynamic which generally has been overlooked. In fact, French jurisprudence from 1881 has recognized this type of offense as a type of provocation to discrimination on a national, racial or religious basis.[2]Thus, under French and European law, the link between boycotting and incitement to discrimination is recognized. This is one of the reasons why Michael Ghnassia, the co-author of this paper, challenged Omar Barghouti who righteously claims the high moral ground, by stating that “the calls for boycott are neither peaceful nor even legal.”[3] On the other side of the Channel, Anthony Julius, member of the legal firm Mishcon de Reya in London, described the meaning of boycotting in his path-breaking study, Trials of the Diaspora: What happens when people are boycotted? The ordinary courtesies of life are no longer extended to them. They are not acknowledged in the street; their goods are not bought; their services are not employed; invitations they hitherto could rely upon dry up; they find themselves isolated in company. The boycott is an act of violence, although of a paradoxical kind – one of recoil and exclusion rather than assault. The boycotted person is pushed away by the ‘general horror and common hate.’ It is a denial amongst other things, of the boycotted person’s freedom of expression …. To limit or deny selfexpression is thus an attack at the root of what it is to be human. Of course, freedom of expression must incorporate freedom of address. It is not sufficient for the exercise of my freedom of expression simply to be free to speak. What matters to me is that people should also be free to hear me. There should at least be the possibility of dialogue. Boycotts put a barrier in front of the speaker. He can speak but he is prevented from communicating. When he addresses another, that other turns away. The boycott thus announces a certain moral distaste; it is always self-congratulatory…. Boycotting is thus an activity especially susceptible to hypocrisy. It implies moral judgments both on the boycotter and boycotted.[4] According to Julius, the boycott is an act of violence. It should also be noted that the process which he described is nearly identical in content to that of delegitimization, through which a member of the international community is deprived of its rights and prerogatives -- not the least, the right to be heard. As we may understand from both French lawyers and from Anthony Julius, the argument of the perpetrators, that they possess a moral, non-violent method of protest is lacking in merit. At the same time that one ponders the reality of the boycott, it is possible to identify an additional level of meaning. In 1984, the Information Department of the Jewish Agency launched a campaign to bring about the repeal of UNGA 3379, “Zionism is Racism.” In this endeavor, it commissioned several studies, and as part of this effort Dr. Ehud Sprinzak, then an Associate Professor at the Hebrew University, described the practical meaning of delegitimization. He explained that the distinguishing characteristic of the new defamation campaign against Israel (and the new anti-Semitism) was a process of dehumanization, which, when brought to its logical conclusion, deprived Israelis and Jews of their commonly accepted human rights. His central thesis was that a “qualitative change ushered in the anti-Zionism of the 70s, a change arising from the fact that Zionism has ceased being an object of delegitimation and had become an object of dehumanization [italics in original].”[5] Sprinzak described the end result of this process: …. The loss of legitimacy effectively means the loss of the right to speak or debate in certain forums. When a political entity is subjected to widespread delegitimization, whatever its spokesmen may have to say on a given concrete subject, even when no particular principle is at stake, is perceived as irrelevant. They are no longer accepted as partners in legitimate discourse, for they themselves are illegitimate. Their position resembles that of patients in a closed mental institution: once committed by the professional board of review, they are treated as mentally incompetent, no matter how cogently they may express themselves.[6] If one goes beyond the terminology and considers the effective meaning of the political war which is being waged against Israel and its supporters, one may observe in the above description a certain coherence of content which identifies elements of hatred, incitement, discrimination, and delegitimization all together and all at once. Decades ago, Sprinzak identified another characteristic of the dynamic of delegitimization to which the boycott belongs. He used the term, “dehumanization.” With the development of new scholarship, particularly in the field of genocide studies, the danger of incitement and dehumanization has been documented. Gregory H. Stanton, President of Genocide Watch, in a 1996 briefing paper which he originally presented at the State Department, described what he termed “The Eight Stages of Genocide”.[7] Incitement belongs to stage 3, which Stanton placed in the category of Dehumanization. Potentially, there is a link between a boycott and future violence. For example, the Nazi boycott of Jewish business which began on April 1, 1933 (and whose slogan was Kauft nicht bei Jueden!)[8]represented one of the earliest stages of the persecution of the Jews. The true nature of Palestinian agitation against Israel and its supporters is not neatly defined and may not be for some time. From an examination of the reports which follow, it is clear that the discourse has reached a different stage. Recent events on college campuses, whether they may be centered on the boycott or the accusation of apartheid, no longer have pretensions of seeking peace or reconciliation. The goal of these protagonists is to delegitimize the State of Israel and bring about regime change. They do not always state this explicitly, but occasionally this happens, as for example in the case of Omar Barghouti’s essay, “Our South African Moment has Arrived.”[9] From the reports that follow, it would be fair to surmise that the proponents of the Palestinian cause are waging a political war whose objectives are the destruction of the State of Israel and silencing its advocates. This is what asymmetrical warfare is all about, and by its nature is a prelude to violence. It is likely that the breadth and intensity of this challenge will increase. It will be our job turn the war around and make sure that our adversaries fail. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------