II. Introduction to Ethics

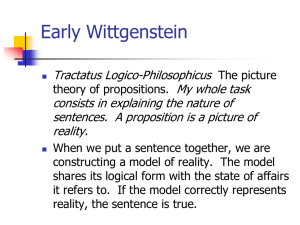

advertisement

II. Introduction to Ethics I. Person, life • Ludwig Wittgenstein was born on April 26, 1889 in Vienna, Austria, to a wealthy industrial family, well situated in cultural Viennese circle. • The family was one of the wealthiest in Vienna, and young Ludwig grew up in a hothouse atmosphere of high culture and privilege. Johann Brahms and Gustav Mahler were frequent visitors to the palatial family home (Palee Wittgenstein) , and Ludwig's brother Paul, a concert pianist who lost an arm in World War I, commissioned works for the left hand by Richard Strauss, Maurice Ravel and Prokofiev. Studies • Wittgenstein originally studied engineering, first in the Realschule in Linz, then in Berlin. In 1908 he went to Manchester to study aeronautics. Following Frege’s (professor of mathematics in Jena) advice he went to Cambridge to study mathematical logic under Bertrand Russell at Trinity College in 1911. Years in Cambridge 1911-1913 • During the years in Cambridge 1911-1913 Wittgenstein worked on the foundation of logic and conducted conversation at the subject with Moore, Keynes, Ramsey. • When the First World War broke out, W. joined the Austrian army, and became a volunteer in the Austrian artillery. He served first on a ship at the Vistula River near Kraków, then in an artillery workshop, and finally was sent to the Russian front where he gained many distinctions for bravery. • In 1918 he was sent to Italy where in the end of the war he became a prisoner of the ITALIANS in Cassino. The Tractatus logico-philosophicus. • During these four years of active service Wittgenstein had written his great work on logic, language and the world. In the camp he finished his one and only work published during his lifetime the Tractatus logicophilosophicus. While he was still in the prison camp he managed to send the Tractatus to Russell. The Tractatus was published firstly in Wien 1921, then in London 1922. The Tractatus • The Tractatus is a highly condensed and aphoristic text on the philosophy of language which climes to present, “on all essential points, the final solution to the problems of philosophy”. Formal relationship between language, thought and the world • The Tractatus posits a close formal relationship between language, thought and the world. There is a direct logical correspondence between the configurations of simple objects in the world, thought in the mind, and words in language. Thus the shape of ideas in the mind and the relationship of words in a sentence are identical in form with the structure of reality or “state of affairs” they represent. Doubts about the philosophy of the Tractatus • He began to have serious doubts ab. the soundness of the philosophy presented in the Tractatus. In 1929 he returned to Cambridge and resumed his philosophical vocation. He became a fellow of Trinity from 1930 onward. • During these first years in Cambridge his conception of philosophy and its problems underwent dramatic changes that are recorded in several volumes of conversations, lecture notes, and letters (e.g., Ludwig Wittgenstein and the Vienna Circle, The Blue and Brown Books, Philosophical Grammar). • He was appointed professor of philosophy in 1939, but served during the Second War as a hospital porter in Guy’s Hospital in London, later as a medical orderly, laboratory assistant in the ROYAL VICTORIA Infirmary, before returning to his academic duties in 1944. He held the chair practically from 1945. The Philosophical Investigations, • In the 1930s and 1940s Wittgenstein conducted seminars at Cambridge, developing most of the ideas that he intended to publish in his second book, Philosophical Investigations. He turned from formal logic to ordinary language, novel reflections on psychology and mathematics, and a general skepticism concerning philosophy's pretensions. • In 1945 he prepared the final manuscript of the Philosophical Investigations, but, at the last minute, withdrew it from publication (and only authorized its posthumous publication). • Retired in 1947 he settled in Ireland, working on Philosophical investigations, a work containing his mature thought which he left for posthumous publication. Aanalogy between words and tools in a tool-box • He draws an analogy between words and tools in a tool-box: …there is a hammer, pliers, a screw-driver, a ruler, a glue-pot, nails and screws. The function of words is as diverse as the function of these objects. It was not that a word had a meaning, rather it had a use. The meaning of a word is its use governed by rules. Wittgenstein’s death • In 1949 he spent some time in America and Ireland. Returning to England the same year with incurable cancer. W. did not seem unhappy at the diagnosis. He said he did not wish to live any longer. He continued to work on his ideas until a few days before his death. The cancer killed him at Cambridge in 1951. • Legend has it that his last words were "Tell them I've had a wonderful life”. Fifteen substantial volumes • His literary executors published volumes of selections from his notebooks including: • Remarks on the foundation of mathematics, • The blue and brown book, • Zettel, • Culture and Value, • Remarks on the phil. Of psychology, • On Certainty, • Notebooks 1914-1916, and some other late writings. Biography: On Wittgenstein’s life. • 1. Brian McGuiness, Wittgenstein and his Time, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1982. • 2. Brian McGuiness, Wittgenstein: A Life. Young Ludwig 1899-1921. London: Duckworth, 1988. • 3. Monk Ray. Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius. London: Vintage, 1990. • 4. Malcolm Norman. Ludwig Wittgenstein: A Memoir. Oxford: Oxford 1984. • 5. Janik Alan & Stephen Toulmin, Wittgenstein’s Vienna, New York. • 6. Rush Rhees, ed. Ludwig Wittgenstein: Personal Recollections. Totowa 1981. • 7. Wittgenstein: A Critical Reader. Ed. by H. J. Glock, Blackwell 2001. “Duty to oneself”, • Monk stresses the all-important connection betw. Wittgenstien’s life and work, religious conversion and philosophy: His logic and his thinking ab. himself being but two aspects of the single “duty to oneself”, this of genius. Being true to oneself • W. was arguing for a morality based on integrity, on being true to oneself, one's impulses - a morality that comes from inside one's self rather than one imposed from outside by rules, principles and duties. “If anyone is unwilling to descend into himself, because it is too painful, he will remain superficial in his writing”. (A commentary reported to Rhees). The use of studying philosophy • “What is the use of studying philosophy, if all that does for you is unable you to talk with some plausibility about some abstruse questions of logic, etc., if it does not improve your thinking about important questions of everyday life..” • “A bad philosopher is like a slum landlord. It is my job to put him out of business.” • But philosophy is very complicated. Why is it so complicated? He asks: It ought to be entirely simple. Philosophy • Philosophy unties, disentangles the knots in our thinking that we have, in a sense, put there. To do this it must make movements that are just as complicated as these knots. Although the result of philosophy is simple, its method cannot be if it is to succeed. The complexity of philosophy is not a complexity of its subject matter, but of our knotted understanding. Tractatus • The Tractatus is a highly condensed and aphoristic text on the philosophy of language which climes to present, “on all essential points, the final solution to the problems of philosophy”. It was recognized from the outset as being one of the key works of its age. The Tractatus’ enigma • Yet even today The Tractatus remains an enigma. • Trying to understand the Tr. we are confronted with two contrasting views about the subject of the book. After apparently seventy pages devoted on logic, theory of meaning, philosophy of mathematics, and natural sciences we are faced with five concluding pages, proposition 6.4 on: a string of theses about subject, will, solipsism, death and the sense of the world, which must lie outside the world. Critique of language • Critique of language was taken to be the crucial instrument of thoughts, the instrument of fighting with slavery of thought and expression which is the enemy of individual integrity, and leaves one defenseless against the political deceptions of corrupt and hypocritical men. A letter to Russell • „In fact you would not understand it without a pervious explanation as it's written in quite short remarks. (This of course means that nobody will understand it); although I believe, it's all as clear as crystal. • The main point is the theory of what can be expressed (gesagt) by props - i.e. by language - (and, which comes to the same, what can be thought) and what cannot be expressed by props, but only shown (geziegt): which, I believe, is the cardinal problem of philosophy. T • his book will perhaps only be understood by those who have themselves already thought the thoughts which are expressed in it. “"The book will … draw a limit to thinking, or rather — not to thinking, but to the expression of thoughts …. The limit can … only be drawn in language and what lies on the other side of the limit will be simply nonsense" (TLP Preface). Structure of Tractatus • Tractatus consists of seven main theses and a string of subordinated theses that make unity - one passage of thoughts. The theses have a well-ordered structure: subtheses comment the preceding main thesis and introduce the next main thesis. The structure of Tracatus corresponds with logical structure of the world. • Witt. holds that the world is ordered in a logical way and can be presented as a collection of facts. Beyond facts there exist nothing. • A given fact is defined as an existing state of affairs • and the state of affairs is defined as a given connection of things. Thought • Thought is a logical picture of facts. • Thought is a sentence with a sense. • Thoughts in logical way picture facts as well as sentences. • Facts are mirrored by sentences. • The world (its structure) can be projected on language. • That is why to analyze the structure of language is to discover the structure of the world. • Thought means sentence which has a sense, and sentence that has a sense is a picture of possible state of affairs. Sentence • Sentence can be true or false. One can decide if a sentence is true or false on the base of reality, the sentence refers to. • If a state of affairs exists, then the sentence is true, if a state of affairs does not exist (but might have existed), then the sentence has only sense, but is false. • There are also sentences which have no sense. They do not refer to reality, but to an impossible state of affairs. Sentence • Sentences are divided into simple and composed. • The composed are constructed by means of the simple sentences. • The simple sentences consist of names. • Simple sentences are functions of names. A name • A name denotes an object. • Configuration of names in a sentence shows connection between objects i.e. states of affairs. The last thesis of Tractatus • „What we cannot speak about, thereof we must kept silence”. • The presiding theses say that limits of our language are the limits of our world. Our linguistic competence or better, what we are able to describe by means of language define our world. The Tractarian theory of language • Words, Witt argued, are representations of objects. • And combining words lead to propositions which are statements about reality, pictures of reality. • The world consists of facts, these facts can be broken down into states of affairs, which in turn can be broken down into combinations of objects. • The world is built from simple objects. • Propositions, statements about reality, i.e. pictures are deliberately constructed verbal representations. W's gives an example: “A gramophone record, the musical idea, the written notes, and the sound waves, all they stand to one another in the same internal relation of depicting that holds between language and the world. They are all constructed according to a common logical pattern.”(4.014). Proposition as picture of reality • “A proposition is a picture of reality: for if I understand a proposition, I know a situation it represents. And I understand the proposition without having had its sense explained to me.” (4. 021). • "We make models of facts form ourselves" and a model is laid against reality like a measure." • The term model (Darstellung) cover architects' blueprints, children's model toys, painted portraits, all sort of patterns; mathematical models (Bilder) are only one species of representations (Darstellungen). A model represents its sense; • "in order to tell whether a model is true or false, we must compare it with reality." 2.223. In order to be a picture there must be sth. in common with what is pictured (2.16). And it is its form of presentation (2.17). There is and must be a logical structure in common betw. a proposition 'The grass is green' and a state of affairs (the grass being green), and it is this commonality of structure which enables language to represent reality. Only in this way can the proposition be true are false: it can only agree or disagree with reality by being a picture of situation. The picture represents or can represent every reality whose form it has. The spatial picture, everything spatial, the colored, everything colored, etc (2.171). Thought as logical picture • The logical picture of the facts is the thought (3.). The totality of true thoughts is a picture of the world 3.01). • The picture, however, cannot represent its form of representation; nor shows it forth (2.172). Beyond naming objects and describing their configurations, models cannot assert anything about them. The conditions for a proposition's having sense • It rests on the possibility of representation or picturing. Names must have a reference, a meaning. • It follows that only factual states of affairs which can be pictured can be represented by meaningful propositions. • What can be said are only propositions of natural science • And this leaves out a great number of statements which are made and used in language. Ethical remarks lacked sense • Moral remarks cannot be translated into, or reduced to, empirical propositions. 'No statement of fact can ever be, or imply a judgment of an absolute value'. • Nor of course can any statement of value imply a statement of fact. • Ethical remarksclacked sense, because no state of affairs is asserted to obtain when we make an ethical judgment. • We cannot point to any state of affairs which embodies or corroborates the moral judgment. We cannot physically perceive the moral, the proof of that is - when we attempt to point to it - to point it out in the situation we might discover that others do not "see" it. Human actions are morally empty • "All propositions are of equal value" 6.4. In 6.432 he writes: "How things are in the world is a matter of complete indifference for what is higher. God does not reveal himself in the world.„ • It means that what happens in the world: famine, disease, etc., natural disasters, are not in themselves evil, wicked. They just are. Nor is human suffering. In Notebook he writes 'the happy man is fulfilling the purpose of existence' . He means who no longer needs to have any purpose except to live, that is to say who is content. The ethical • But what would the ethical be if it could be expressed? • It is the mystical. • This includes the sense of world which must lie outside the world and so transcendent the expression 6.41. • It also includes that the world exists. We wonder at the meaning of life, at the existence of the world. • But there is no answer here that can be put into words, and so no question, and no problem and no riddle: “When the answer cannot be put into words, neither can the question be put into words. The riddle does not exist. If the question can be framed at all, it is also possible to answer it.” 6.5. Value cannot lie within the world • The idea had two negative implications: everything which is important to human life lies beyond the reach of science, as he says in the Tractatus: “We feel that even when all possible scientific questions have been answered, the problems of life remain completely untouched. Of course there are then no questions left, and this itself is the answer.” 6.52. • 'It is clear that ethics cannot be put in words." 6.421. There are therefore no ethical propositions 6.42. • Indeed, it is not just that there are no ethical propositions, for the whole business of language was making propositions, there are no meaningful ethical remarks or utterances. Notebooks 1914-16 • He asks: What gives meaning to life and the world? • The question is problematic, because what happens in the world is purely contingent and does not manifest any kind of moral necessity. How can be meaning and value in the seemingly nihilistic world of modern science, where the world has been divorced from any conception of value? • He asks: What gives meaning to life and the world? The question is problematic, because what happens in the world is purely contingent and does not manifest any kind of moral necessity. How can be meaning and value in the seemingly nihilistic world of modern science, where the world has been divorced from any conception of value? Will and value • Like Kant Wittgenstein locates value within a will which is not a part of the empirical world, the ordinary empirical will is simply another fact in the world and, as such, cannot be neither good or bad. Will and world • The will is not capable of effecting changes in the world. All that exists in the world, all facts are contingent. • “The world is independent of my will”. Tr.6.373. “Even if all we wish for were to happen, still this would only be a favor granted by fate, so to speak: for there is no logical connection between the will and the world, which would guarantee it, and the supposed physical connection itself is surely not something that we would will.” 6.374. The ethical will can alter only the limits of the world • "If the good or bad exercise of the will does alter the world, it can only alter the limits of the world, the way we look at the world, not the facts – not what can be expressed by means of language. In short the effect must be that it becomes an altogether different world. It must, so to speak, wax and wane as a whole. The world of the happy man is a different one from that of the unhappy man.” 6.43 The world is my world; it is seen in the fact that, the limits of language (of that language which alone I understand) mean the limits of my world. Tr. 5.62. Subject and ethical meaning • The subject gives ethical meaning to life through the way in which it views the world as a whole. In Tr. 6.45. he says that “to view the world sub specie aeterni (from the viewpoint of eternity) is to view it as a whole – a limited whole or a as created by God. • He also connects this idea to both ethics and aesthetics: the work of art is the object seen sub specie aeternitatis; and the good life is the world seen sub specie aeternitatis. • This is the connection between art and life. Viewing the world as a limited unity is analogous to viewing it as an aesthetic object, in that contingent facts acquire a meaning. In other words, our sense of meaningfulness of an object, or the world, can come and go depending on our perspective on it. Witt.: “ethical will alters only the limits of the world, so that it must, so to speak, wax and wane as a whole, as if by accession or loss of meaning. Notebooks, 73. Moral imperative • Witt. saw knowing of the self as a moral imperative. It was the same need to eradicate logical flaws as any other kind of deception. Logic and ethics are one. It is the Kantian freedom of choosing the good or the bad, that manifests itself in consciousness of sin and in repentance. As the empirical ego man is a part of nature, the world of causality. But as the intelligible ego is free. • Freedom lies above the bidding of the empirical ego: Duty is duty to oneself, duty of the empirical ego to the intelligible ego. M159. Experiences of the First War 'What do I know about God and the purpose of life?' • • • • • • • • • • that I am placed in it like my eye in the visual field. That sth. about it is problematic, which we call its meaning. That this meaning does not lie in it but outside it. That life is the world. That my will is good or evil. Therefore that good and evil are somehow connected with the meaning of the world. The meaning of life, i.e. the meaning of the world, we can call God. And connect with this the comparison of God to a father. To pry is to think about the meaning of life. I cannot bend the happenings of the world to my will: I am completely powerless. • I can only make myself independent of the world - and so in a certain sense master it - by renouncing any influence on happenings. • Later' Fear in the face of death is the best sign of a false, i.e. a bad life' • To believe in a God means to understand the meaning of life. • To believe in God means to see that facts of the world are not the end of the matter. • To believe in God means to see that life has a meaning. • The world id given to me, i.e. my will enters the world completely from the outside into sth. that is already there. • However this may be, at any rate we are in a certain sense dependent, and what we were dependent on we can call God. • In this sense God would simply be the fate, or, what is the same thing: The world which is independent of our will. • I can make myself independent of fate. • ...When my conscience upsets my equilibrium, then I am not in agreement with Sth. But what is it? Is it the world? Certainly it is correct to say: Conscience is the voice of God. How things stand, is God. God is how things stand. (He means - How they stand in the world and how they stand in oneself) . This is precisely what is, the unreasoning life, a false view of life.' 'You know what you have to do to live happily'. Summary • Ethics is not a science of morality. It is not a branch of knowledge, like geometry or chemistry. • It has nth. to do with facts but the paradoxical. • Only a good man knows what values are, only he can communicate them. • Viewing the world as a totality, as when it is experienced as a miracle created by God, constitutes the “ethical space’ in which value and meaning can enter into life. • For without the unifying perspective on life and the world there are only ethically neutral facts. • For. W. ethical self is disconnected from the common public world not only in that it can produce no effects in that world, but also in that its moral perspective is essentially private.