HISTORY 308: WOMEN, POWER, AND POLITICS IN EARLY

advertisement

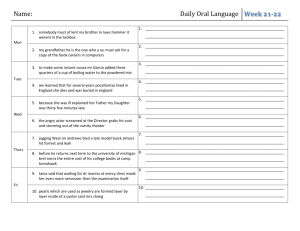

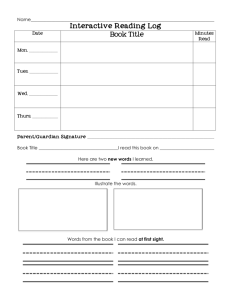

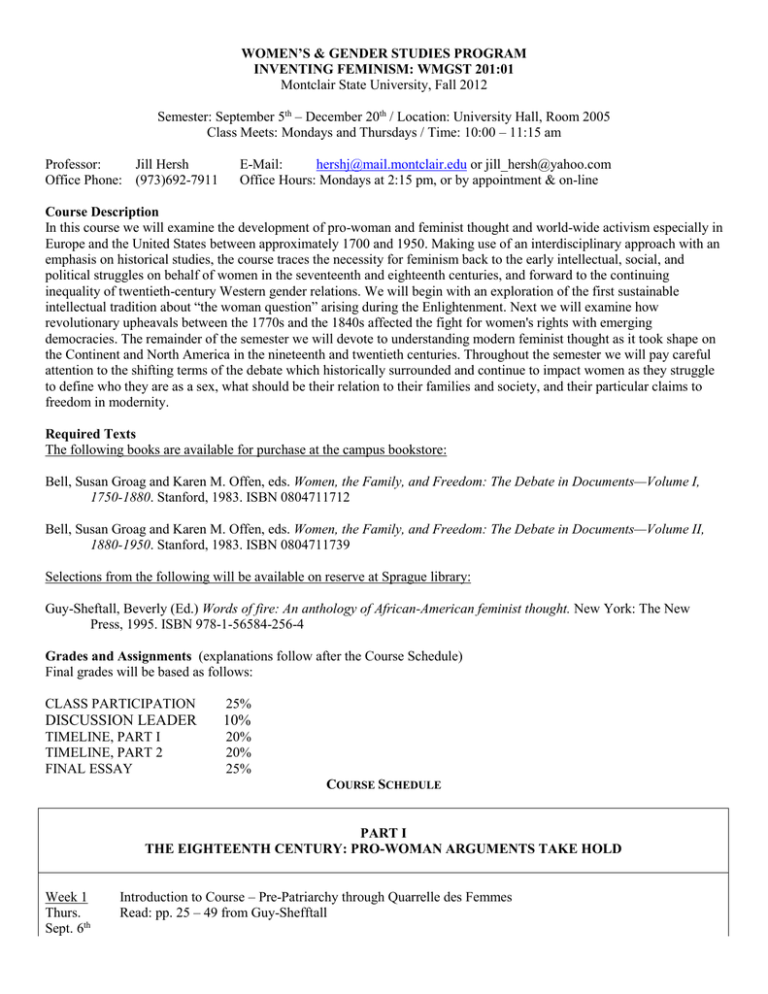

WOMEN’S & GENDER STUDIES PROGRAM INVENTING FEMINISM: WMGST 201:01 Montclair State University, Fall 2012 Semester: September 5th – December 20th / Location: University Hall, Room 2005 Class Meets: Mondays and Thursdays / Time: 10:00 – 11:15 am Professor: Jill Hersh Office Phone: (973)692-7911 E-Mail: hershj@mail.montclair.edu or jill_hersh@yahoo.com Office Hours: Mondays at 2:15 pm, or by appointment & on-line Course Description In this course we will examine the development of pro-woman and feminist thought and world-wide activism especially in Europe and the United States between approximately 1700 and 1950. Making use of an interdisciplinary approach with an emphasis on historical studies, the course traces the necessity for feminism back to the early intellectual, social, and political struggles on behalf of women in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and forward to the continuing inequality of twentieth-century Western gender relations. We will begin with an exploration of the first sustainable intellectual tradition about “the woman question” arising during the Enlightenment. Next we will examine how revolutionary upheavals between the 1770s and the 1840s affected the fight for women's rights with emerging democracies. The remainder of the semester we will devote to understanding modern feminist thought as it took shape on the Continent and North America in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Throughout the semester we will pay careful attention to the shifting terms of the debate which historically surrounded and continue to impact women as they struggle to define who they are as a sex, what should be their relation to their families and society, and their particular claims to freedom in modernity. Required Texts The following books are available for purchase at the campus bookstore: Bell, Susan Groag and Karen M. Offen, eds. Women, the Family, and Freedom: The Debate in Documents—Volume I, 1750-1880. Stanford, 1983. ISBN 0804711712 Bell, Susan Groag and Karen M. Offen, eds. Women, the Family, and Freedom: The Debate in Documents—Volume II, 1880-1950. Stanford, 1983. ISBN 0804711739 Selections from the following will be available on reserve at Sprague library: Guy-Sheftall, Beverly (Ed.) Words of fire: An anthology of African-American feminist thought. New York: The New Press, 1995. ISBN 978-1-56584-256-4 Grades and Assignments (explanations follow after the Course Schedule) Final grades will be based as follows: CLASS PARTICIPATION 25% DISCUSSION LEADER 10% TIMELINE, PART I TIMELINE, PART 2 FINAL ESSAY 20% 20% 25% COURSE SCHEDULE PART I THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY: PRO-WOMAN ARGUMENTS TAKE HOLD Week 1 Thurs. Sept. 6th Introduction to Course – Pre-Patriarchy through Quarrelle des Femmes Read: pp. 25 – 49 from Guy-Shefftall 2 Week 2 Introduction: The Evolution of Feminist Consciousness Among African-AmericanWomen Mon. Sept. 10th Thurs. Sept. 13th Read: pp. 51-76 from Guy-Sheftall Week 3 Western Misogyny and Pro-Woman thought before 1700 Mon. Sept. Select Themes & Discussion Leader Dates 17th Thurs. Sept. 20th Offen/Bell, WFF Vol. I: “General Introduction” (pp. 1-11) “Introduction to Part I: 1750-1830” (pp. 13-23) Ch. 1: Docs. 1-9 (With documents, always read all relevant section introductions and document headers. This will help you to make sense of the documents themselves.) Week 4 1700-1810: The Enlightenment Marriage Debate Mon. Sept. 24th Thurs. Sept. 27th Offen/Bell, WFF Vol. I: Ch. 2: Docs. 10-12, 15, 17-21 PART II THE NINETEENTH CENTURY: THE EMERGENCE OF FEMINISM Week 5 Mon. Oct. 1st 1750-1830: The Enlightenment Education Debate *Timeline Part 1 due today in class* Thurs., Oct. 4th Offen/Bell, WFF Vol. I: Ch. 3: Docs. 24-32 Week 6 Mon. Oct. 8th 1789-1830: Revolution, Republican Motherhood, and Women’s Rights Thurs., Oct. 11th Read: Offen/Bell, WFF Vol. I: “Introduction to Part II: 1830-1848” (pp. 133-141) Ch. 4: Docs. 35, 40, 41 Ch. 5: Docs. 43, 44, 46, 47 Ch. 6: Docs. 49, 50, 53, 54 3 Ch. 7: Docs. 67, 68 Week 7 Mon. Oct. 15th 1830-1848: Renewing Claims for Women Thurs., Oct. 18th Read: Offen/Bell, WFF Vol. I: “Introduction to Part III: 1848-1860” (pp. 239-244) Ch. 8: Docs. 69, 71, 72, 74, 75, 76 Ch. 9: Docs. 84, 85, 88 Ch. 10: Docs. 90, 92 Week 8 Mon. Oct. 22nd 1848-1870: The Woman Question Watch: Not for Ourselves Alone: The Story of Elizabeth Cady Stanton & Susan B. Anthony (part 1) Thurs., Oct. 25th Read: Offen/Bell, WFF Vol. I: “Introduction to Part IV: 1860-1880” (pp. 359-366) Ch. 12: Docs. 102, 105, 106, 108, 110 Ch. 13: Docs. 113, 115, 116 Ch. 15: Docs. 132, 133 Ch. 16: Docs. 135, 136, 137 Week 9 Mon. Oct. 29th 1870-1890: The First International Woman’s Movement Watch: Not for Ourselves Alone: The Story of Elizabeth Cady Stanton & Susan B. Anthony (part 2) Thurs., Nov. 1st Week 10 Mon. Nov. 5th Thurs., Nov. 8th Week 11 Mon. Nov. 12th Catch-Up 1890-1914: The New Woman (Hand in complete timeline including a corrected version of Part 1. Part 1 needs to be corrected according to suggestions from previous assignment feedback.) Offen/Bell, WFF Vol. II: Ch. 4: Docs. 37, 38, 43 Ch. 5: Docs. 47, 53, 54 Ch. 6: Docs. 55, 56, 57, 58, 60, 61, 63 1890-1914: Feminism and the Nation-State 4 Thurs., Nov. 15th Mon. Nov. 5th Offen/Bell, WFF Vol. II: Read: Introduction to Part II: 1914-1950 (pp. 247-258) Ch. 7: Docs. 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71 Ch. 7: Docs. 74, 75 Ch. 8: Docs. 76, 77, 80 PART III THE TWENTIETH CENTURY: FEMINISM IN THE MODERN AGE Week 12 Mon. Nov. 19th 1900-1920: Before, During, and After World War I Watch in class: Iron Jawed Angels (part1) Thurs., Nov. 22nd THANKSGIVING HOLIDAY Week 13 Mon. Nov. 26th The American Battle for Suffrage Watch in class: Iron Jawed Angels (part 2) Thurs., Nov. 29th Read: Offen/Bell, WFF Vol. II: Ch. 9: Docs. 81, 82, 83, 84, 86, 87 Ch. 10: Docs. 92, 93, 98, 99, 100 Week 14 Mon. Dec. 3rd 1920-1938: Motherhood and Womanhood in War-Torn Europe Thurs., Dec. 6th Read: Week 15 Mon. Dec. 10th 1930-1950: Before, During, and After World War II Thurs., Dec. 13th Write: Final Essay Exam Week Mon. Dec. 17th Due: Final Essay Offen/Bell, WFF Vol. II: Ch. 11: Docs. 104, 105, 106, 108, 110, 112 Ch. 12: Docs. 117, 119, 120 5 Assignment Guidelines 1. Class Participation: This course is primarily structured around intensive discussion of the assigned readings, not around passive listening to lectures. Your in-class active verbal engagement with the material and with your fellow students is a very important measure of your progress in the course; thus participation counts as a full quarter of your final grade. To ensure quality participation, you need to complete the assigned reading in advance of each class, and attend class each day prepared to discuss the reading. Participation will be graded on a weekly basis according to how well prepared you demonstrate yourself to be, by actively and regularly sharing your ideas, questions, comments, and criticisms about the readings aloud in class discussions. Be aware that mere physical presence in the classroom does not in itself constitute participation and will not earn you any credit toward this grade. If you are uncomfortable with speaking in class, please talk with the professor about it privately, as early in the semester as possible. Part of your evaluation comes from your engagement as a Discussion Leader on the date assigned to you. This role involves facilitating class discussion, presentation of relevant material, addressing readings & asking questions. 2. Timeline: You will be assigned recurring themes in the semester’s materials (if you truly prefer a different theme, you may request to change topics with another ). As we work through the course readings, create a historical timeline of documents that traces your assigned theme in time relative to other major developments in the invention of feminism and history more generally. Week by week, identify every assigned document that touches on your themes, and place each relevant document in your timeline. In the timeline, briefly explain (one-page maximum ) each document’s position in relation to your assigned theme. For example, how do attitudes, arguments, and positions regarding your theme develop (or stand still) and progress (or regress) over time? How do the documents “speak” to one another across time and space? Identify ideas in one document which are carried forward from some earlier document(s). Identify when an author is refuting or supporting another author or document. It may also help to include a short description of each author the first time they appear in your time line. FORMAT: Can include images and supplementary information from credible, external materials along with primary source material. I am open to anything as long as it is clear, typed (no handwritten work accepted), makes sense, and can be carried home in a folder or bag. However, please do not turn it into an art project. I expect you to concentrate on the ideas and content of the documents. DUE: 2x during semester; see syllabus for due-dates. NOTE: The second hand-in must incorporate the earlier hand-in, with a clear demarcation separating the two parts. Any comments and corrections must be addressed for the 2nd hand-in. 3. Discussion Leader: At least once during the semester, based on a date(s) you have chosen near the start of the semester, you will lead a discussion on the material assigned for that period. This includes making key points, asking guiding questions, providing support or documentation, engaging in an interactive activity with the class and responding to class mate’s comments. Submit your notes to the instructor. 4. Final Essay: An essay will be handed in instead of a final exam. ASSIGNMENT: analyze change over time in regard to your timeline theme, circa 1700-1950 (not every theme will cover the whole period; some start later, some end earlier, some do both). You need to discuss specific documents, and quote them appropriately, to build your analytical argument. LENGTH/FORMAT: 6-7 double-spaced pages, with standard font (Times, e.g.), and size (12 point). Please refer to the introductory sections and document headnotes in WFF as needed for historical background, but please do not extensively research and source non-course materials for this essay. Refer to website for documentation instructions. NOTE: This essay must be submitted on time and in hard-copy form; it cannot be handed in late; failure to produce it on time will result in an “F” for the course. Alternative: Select a different theme and/or topic. 5. Make-ups and late assignments: Late papers: any assignment handed in after the deadline will lose one third of a grade for every day of lateness, weekends included. Only hard-copy (paper) work will be accepted: owing to the frequency of technical glitches and computer viruses, I will not accept anything submitted on disk or by e-mail. Except for an emergency of which I have been notified at least several days in advance, the final essay absolutely cannot be handed in late. I reserve the right to judge what constitutes an emergency. Attendance, Cell Phone Policy, Class Cancellation 6 Attendance is required. I recognize that students may occasionally need to miss class because of a medical or family emergency, or because of a conflict with another school activity, such as a field trip, or because of a conflict with employment responsibilities, or because of a day of religious observance not recognized by the school calendar. For this reason, I allow each student one “free” absence. You thus have the generous option of missing one whole class or two half-classes penalty-free. However, each absence in excess of this limit will result in a one-half of a leter grade reduction in the participation portion and a one-third of a letter grade reduction in the student’s final grade. Please bear in mind that this policy applies to all absences, regardless of their nature. A student who skips two classes early in the semester and then misses a third class because of an illness later on will still incur a reduction in his or her final grade. Athletes should consult their game schedules early in the semester to make sure that they will not have conflicts with this policy. Working students should likewise discuss this policy with their employers. Students whose religious observations are not formally recognized by the MSU schedule should also plan accordingly. Regarding late arrivals, bathroom breaks, and early departures: I expect every student to arrive on time for every class, and remain seated for the duration of the class period. Students who arrive late disturb a class already in progress, so please make every effort to be on time. Early departures are equally disruptive: by enrolling in this class, you have made a commitment to be present for the complete period of each meeting. Do not schedule other events that conflict with this prior commitment. For the same reason, bathroom breaks during class are unacceptable except for persons with special needs (please discuss with me privately). Plan your time accordingly! If you must leave the room during class, I expect you to do so politely and quietly. Three late arrivals and/or early departures will count as one absence. You are responsible for all material covered even if you’re not present. Cell Phone Policy: Out of respect for preserving a positive learning environment, all cell phones, beepers, MP3 players, and other portable noise-making devices must be SILENCED for the duration of the class period. If need be, students will be reminded and/or penalized for disrupting class with noisemaking devices (phones, etc.). If students refuse to demonstrate respect for one another and for the professor by not silencing their phones before class begins, and they do not admit to being the cause of the problem, I reserve the right to deduct points from the entire class’s grades. Inclement Weather and other unknowns: If travel conditions or other problems prevent me, the professor, from reaching campus on a class day I will notify the entire class using your MSU mail.montclair.edu e-mail account. On snowy days, please check your e-mail the morning of our scheduled class day. Honor in Academia I expect you to demonstrate at least the rudiments of proper scholarly documentation in all your writing, and be able to use the citation style appropriate to the History discipline. This means that in your essays I require that you document all sources (referred to or quoted) with proper footnotes, NOT in-text citations, NOT author-date references, and NOT endnotes. You are to follow the Chicago Manual of Style (a.k.a. Turabian style), the standard style guide used by historians. Links on our course website can help you to improve your writing and documentation skills. Plagiarism (defined in the American Heritage Dictionary as “using and passing off as one’s own the ideas or writings of another”) is an extremely serious academic offense. Any evidence of plagiarism discovered in your written work will automatically result in a grade of “F” for the assignment, potentially an “F” for the final course grade, and in the worst cases, suspension or expulsion from MSU. The cases deserving the strongest punishment involve papers purchased or stolen, but most plagiarism is the result of copying texts and pretending they are your own words. How do you avoid plagiarism? Very simple: (1) When using another’s words directly (quoting) or indirectly (paraphrase), you must put quotation marks around ALL direct quotes and, in a footnote, cite the precise source (author, title of work, page number) of each quote and/or paraphrase. (2) When you write something which depends directly upon another’s ideas, even if you are not quoting directly or paraphrasing, you must cite the specific reference, including page number. (3) If you are ever uncertain about how closely you are depending on another’s idea, cite the work (and relevant page numbers) in question! (4) Whenever possible, completely reformulate ideas into your own words and create your own new independent argument. In short, think for yourself, while acknowledging that we all depend on others for our intellectual advancement. 7 9 TIMELINE THEMES: Include but are not limited to the following questions 1. Marriage: what should be the purpose of marriage? Within the marital relationship, who should govern: the husband, the wife, or both equally? Who has the power of deciding whether, when, or whom a woman should marry: her guardians or herself? Is it a good or a bad idea for women to have the freedom to make these choices? What are the repercussions of allowing or forbidding these options for women, for men, for families, for children, for the state, for the church? 2. Education for women: should women be educated, yes or no? Is female education a good or bad idea, and why and in what way is it good or bad? Should girls’ education be the same in content as boys’ education or different? co-ed or separate? What is appropriate and inappropriate subject matter for girls and women in school? Should girls receive primary education only, or advanced education (university, professional, etc) too? What is the social function of educating women, and who are women to be educated for: themselves, or others (husbands, family, society)? 3. Women’s roles as wives: what responsibilities and duties do they owe their husband, what to the state? How and where should they learn these duties, and from whom should they learn? Are they products of nature or nurture? 4. Women’s roles as mothers: what responsibilities and duties do mothers owe their children, their husband, the state? How and where should they learn these duties, and from whom should they learn? 5. Women’s housework duties as a reason to keep women in the home and/or as a reason for women to participate in society (the “social housekeeping” argument):: glory or burden? Is housework best done solo by the wife, or shared with the husband, or shared with a larger community of fellow-workers, or delegated to servants and machines? Is housework meritorious in itself? Is it beneficial to women, or to men, or to society at large, that women stay home? Or are household duties responsible for holding back women’s social and political advancement? what can women do as women for the betterment of society? Do their traditional housekeeping duties provide special training for larger social roles for women? Does their gender make them natural pacifiers and healers? 6. Women as political participants: Can women participate in politics (e.g., do they have the physical, mental, intellectual, and rational abilities necessary)? Should they be permitted to participate in politics, or restricted (even banned) from participation? If allowed to participate, what should this participation consist of (e.g., joining political clubs, voting, campaigning for legislation and/or office, office holding, law-making, etc.)? Why might letting women participate in politics be a bad idea? Why might it be a good idea? Who would benefit, and who would be hurt, by women’s political participation? 7. Reproductive freedom for women: the right to choose whether and when to be mothers, and what sort of mothers to be; the right to choose how many children to have; the right to identify paternity; the right to sexual pleasure; the right to contraception; the right to sexual knowledge. Why and for whom (women, men, children, the state, the church) are such choices good ideas or bad ideas? whose voices and opinions should matter most in making these decisions: the woman’s, her partner’s, the state, the church? 8. Separate spheres for men and women: is it a good or a bad idea to divide women’s and men’s worlds, responsibilities, and lived experiences between public & private? Is it a realistic expectation or a fantasy to have a gendered division of labor? Does this ideology benefit men? Does it benefit women? how does it help or hinder women’s social, political, and economic advancement? 9. Equality versus difference: are women the same as men and thus deserving of equal treatment in the realms of society, politics, law, education, business, culture? Or are women different from men, and thus deserving of special treatment in the realms of society, politics, law, education, business, culture? Can equality or difference be proven? If it is impossible to prove, of what value is the question, and to whom? How are racism, classism, nationalism and ageism negotiated?