Virtue theory / Natural Law

Natural

Law/Virtue

Ethics

Morality and Human Nature

Natural Law Theory

Based upon assumption that the good is consistent with fundamental design

Not the laws of nature, those laws are descriptive

Moral laws – prescriptive in that they tell us how we ought to behave

Historical Origins: Aristotle (through Aquinas)

An observer of Nature

His teleological view provides a conclusion about human good

Aquinas’ Hierarchy

Eternal Law

The law of God’s regulative reason

Natural Law

That part of God’s Law that is incorporated into human nature

Divine Law

The Law that man receives by special revelation from God

Human Law

Law devised by man for specific purposes

Natural Inclinations

Life

Natural inclination to self-preservation

Procreation

Natural inclination to reproduce

Knowledge

Natural inclination to learn

Sociability

Qualifying Principles

Principle of Forfeiture

A person who threatens the life of an innocent person forfeits his own right to life

Principle or Doctrine of Double Effect

Distinguishes between the intended and the foreseen but unintended consequences of actions

Doctrine of Double-Effect

The act is good in itself

The bad effect is unavoidable

The intention of the actor is good

The bad effect(s) are not part of the purpose

Key point are: “intentions” and “avoidability ”

Applying Double-Effect

Is the act permissible?

Yes

Is the bad effect avoidable?

No

Is the bad effect the means of producing the good effect?

Not

Intended

Is the bad effect proportionate?

Yes

Passes

Yes No Yes

Intended

No

Not permissible - Forbidden

Evaluating Natural Law Theory

Determination of actions is a result of seeing moral law in human nature

Can the way things are by nature provide a basis for knowing how they ought to be?

Chance, direction, and the purpose of life

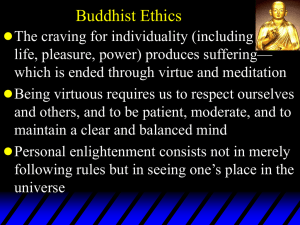

Virtue Ethics

• Focuses on the character of the moral agent performing the action

Intentions will be an important consideration but will not be the only consideration

Consequences may also be important

Principles may also be important

• According to virtue ethics, an action is right if and only if it is what a moral agent with a virtuous character would do in those circumstances

Aristotle on the Virtues

Believed that the ultimate good for man was

eudaimonia (i.e., living a fulfilling, satisfying life)

Believed a person had to develop in themself certain virtues of character, in order to achieve eudaimonia

Virtues included courage, self-restraint, justice, temperance, honesty, benevolence, love of knowledge, generosity, etc.

Most important virtue was phronesis, practical wisdom, which guided one as to when particular virtues were appropriately displayed

Two Types of Virtue

Intellectual virtues represent excellences in reasoning skills that can be taught through inquiry and study.

Moral virtues, by contrast, are products of habit that begin in childhood and are strengthened in adult life.

The Golden Mean

• Aristotle also spoke of the importance of

“The Golden Mean”

• Essentially states that each virtue should be displayed at an appropriate level: not too little, not too much

Too little courage is cowardice, too much courage is recklessness

Lack of honesty is a vice, but being too honest is also a vice

Every science, investigation or action aims at some good. Such good exists in a hierarchy, with the lesser goods being instrumental in the seeking of higher goods, but many things are good in and of themselves.

The highest good will be the final goal of purposeful striving, something good for its own sake. For humans this good is eudaimonia (happiness/flourishing), which is always an end in itself.

The arête (excellence/virtue) of anything resides in its proper function.

The proper function of human beings, and therefore their moral excellence ( arête ), resides in the “active life of the rational element.”

Therefore, the good for human beings is “an activity of the soul in conformity with excellence/virtue.” Such a life necessarily involves acting in accordance with reason.

To act in accordance with reason is a matter of observing the principle of the mean relative to us, i.e. finding the appropriate response between excess and deficiency in a particular situation.

The traditional virtues, e.g. courage, all fit within this scheme

Virtue ethics is not concerned so much with actions or duties as with the development of character.

The development of a proper character is what will lead to proper action, not simply conformity to some rule or duty.

Thus virtue ethics concerns itself more with

being the type of individual who will make proper moral decisions rather than with defining rules/duties which will direct action independent of the individual who is faced with a moral decision.

Contemporary Virtue Ethics

Virtue Theory revived in late 20th century due to dissatisfaction with consequentialist and deontological theories

Universalizes virtue as the basis of the theory

All moral agents should seek to develop a virtuous character

Right action is based upon what a person with a virtuous character would do in those circumstances

Correct answers to moral problems can only be obtained through understanding of the virtues

Consequences and principles are merely tools to aid the moral agent

William Frankena – “A Critique of Virtue-Based Ethics”

“principles without traits are impotent and traits without principles are blind”

Virtue ethics defines traits of character that we admire, but cannot provide a satisfactory explanation for why we should admire those specific traits over others.

Continued.

Principles without dispositions toward action are likewise without teeth.

Frankena sees the two approaches as complementary, rather than competitive