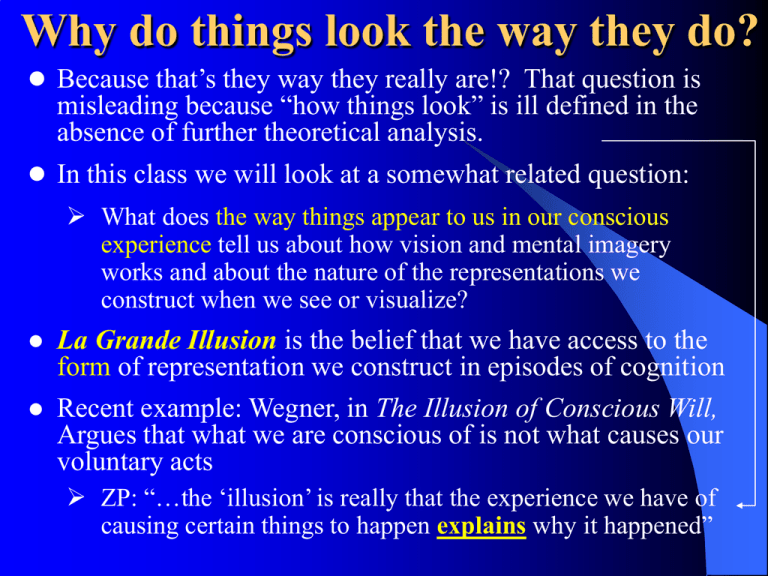

Why do things look the way they do?

advertisement

Why do things look the way they do? Because that’s they way they really are!? That question is misleading because “how things look” is ill defined in the absence of further theoretical analysis. In this class we will look at a somewhat related question: What does the way things appear to us in our conscious experience tell us about how vision and mental imagery works and about the nature of the representations we construct when we see or visualize? La Grande Illusion is the belief that we have access to the form of representation we construct in episodes of cognition Recent example: Wegner, in The Illusion of Conscious Will, Argues that what we are conscious of is not what causes our voluntary acts ZP: “…the ‘illusion’ is really that the experience we have of causing certain things to happen explains why it happened” This is what our conscious experience suggests goes on in vision… This is what the demands of explanation suggests must be going on in vision… Subjective experience suggests that when we see, we are examining an inner display Are there any reasons (other than conscious experience) for taking this view seriously? The completion of percepts from partial information Blind spot, resolution and color sensitivity ‘amodal completion’ (most scene objects are occluded) Completions have real behavioral consequences ‘illusory contours’ and amodal completions act in many ways like real figures Visual representations appear to be panoramic, stable, and in an allocentric frame of reference The superposition theory has a lot of intuitive appeal Completions … Where’s Waldo? Standard view of saccadic integration by superposition The superposition view fails O'Regan, J. K., & Lévy-Schoen, A. (1983). Integrating visual information from successive fixations: Does trans-saccadic fusion exist? Vision Research, 23(8), 765-768. Visual interpretation is local Partly Ambiguous Unambiguous #1 Unambiguous #2 Visual interpretation is local Visual interpretation is local Coordinating the interpretations among parts is more difficult if they are not both visible at the same time When temporal integration occurs is shows the effect of memory load Higher memory load Lower memory load When temporal integration occurs is shows the effect of memory load When temporal integration occurs order of presentation is important Errors in recall suggest how visual information is encoded Children have very good visual memory, yet often make egregious errors of recall Errors in relative orientation often take a canonical form Errors in reproducing a 3D image preserve 3D information Errors in recall suggest how visual information is encoded Children more often confuse left-right than rotated forms Errors in imitating actions is another source of evidence Ability to manipulate and recall patterns depends on their conceptual, not geometric, complexity Difficulty in superimposing shapes depends on they are conceptualized Look at first two shapes and superimpose them in your mind; then draw (or select one) that is their superposition Many studies have shown that memory for shapes is dependent on the conceptual vocabulary available for encoding them e.g., recall of chess positions by beginners and masters Finally, the phenomenology of seeing (including its completeness, its filled-out details, and its panoramic scope) turns out to be an illusion! We see far less, and with far less detail and scope, than our phenomenology suggests Objectively, outside a small region called the fovea, we are colorblind and our sight is so bad we are legally blind. The rest of the visual field is seriously distorted and even in the fovea not all colors are in focus at once. More importantly, we register surprisingly little of what is in our field of view. Despite the subjective impression that we can see a great deal that we cannot report, recent evidence suggests that we cannot even tell when things change as we watch. What changes between flashes? Harborside Airplane Helicopter Dinner Farm scene Paris corner Where does this leave us? Should we conclude that seeing is a process of constructing conceptual descriptions? Most cognitive scientists and AI people would say yes, although there would be several types of exception. There remains the possibility that for very short durations (e.g. 0.25 sec) there is a form of representation very like visual persistence – sometimes called an ‘iconic storage’ (Sperling, 1960). From a neuroscience perspective there is evidence of a neural representation in early vision – in primary visual cortex – that is retinotopic and therefore “pictorial.” Doesn’t this suggest that a ‘picture” is available in the brain in vision? We shall see later that this evidence is seriously misleading and does not support a picture theory of working memory or LTM A major theme of this course will be to show that an important mechanism of vision is not conceptual but causal: Visual Indexes Many people continue to hold a version of the “picture theory” of mental representation in mental imagery. More on this later. Conceptual & Methodological Problems in the study of Visual Perception There is a problem about what it means to see: Ordinary usage confounds: seeing X, seeing X as R, seeing that P, and believing that P. Distinguishing these is a cottage industry in philosophy. Some examples of the prescientific sense of see and why it is a problem (Droodles, “looks like”) Examples of droodles Ordinary language also confounds the content and the vehicle of perception: what perceptual representations are about and what properties the representations themselves have There is a serious problem about what to make of phenomenology – about the conscious experience of seeing. In view of how misleading subjective experience can be, and in view of the fact that what progress there is cognitive science has been made by ignoring the distinction between processes of which we are consciously aware and those of which we have no conscious experience. Cognitive Science, unlike philosophy, has tended to shy away from the evidence of introspection. Conceptual & Methodological Problems in the study of Visual Perception Part of the puzzle about vision rests on the failure to make certain distinctions (such as those alluded to earlier: between seeing and believing, between content and form). These two distinctions will play a major role in our later discussion. The question posed at the beginning of this lecture, Why do things look the way they do? asks why the appearance is conceptualized (or described) a certain way. The difficulty with this idea is dramatized by the Wittgenstein story. What does “how things look” mean? We speak of someone “looking sick,” or “looking happy” or of the weather “looking like it’s going to snow.” This informal sense of looking is too diverse to be useful. A story due to Wittgenstein (as told by Tom Stoppard), goes: Meeting a friend in the hall, a philosopher says, “Tell me, why do people always say it was natural for men to assume that the sun went around the earth rather than that the earth was rotating?” His friend said, “Well, obviously, because it just looks as if the sun was going round the earth.” To which the philosopher replied, “Well, what would it have looked like if it had looked as if the earth was rotating?” The problematic nature of How Things Look will become even more apparent when we discuss mental imagery later. As a take-home exercise you might think about “Why do mental images look like what they are images of?” Conceptual & Methodological Problems in the study of Visual Perception An important distinction that I will address only briefly (but is covered in Chapters 2 and 3) is between seeing and coming to have a belief about what one is seeing. This is crucial to my claim about the Cognitive Impenetrability of Vision or the view of vision as an architectural module. The development of Signal Detection Theory alerted us to the fact that signal detection involves at least two stages: a detection stage and a response selection or decision stage, the latter of which is the only stage that is cognitively penetrable.