European Monetary Integration

advertisement

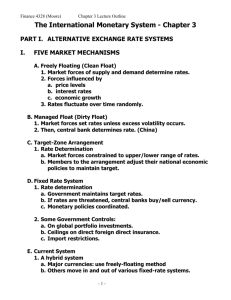

Macroeconomic Policies in the EU Course given by Kiril Strahilov, PhD at MGIMO, Russia 7-10 October 2006 Course Outline 1. European Macroeconomic Policies 1.1. Brief Revision of European Monetary Integration 1.2. Recent Macroeconomic Developments in the Euro Area 1.3. Macroeconomic Policy Settings 1.4. The External Dimension. 2. The Euro Area as an Optimum Currency Area (OCA) 2.1. Benefits of OCAs 2.2. Costs of OCAs 2.3. Costs and Benefits compared 3. Monetary and Fiscal Policies in the Euro Area. 9) 3.1. Institutional Aspects of the ECB: Credibility, Accountability and Independence. 3.2. The Transmission Mechanism of Monetary Policy 3.3.The Reform of the Stability and Growth Pact 4. The Euro Area Enlargement The Road of the Ten new EU Members towards EMU 5. European Unemployment Basic Facts 5.1. The Initial Rise of Unemployment: the Role of Shocks 5.2. Continuing Unemployment: Sources of Persistence 5.3. High Unemployment: the Role of Institutions 2 Bibliography • Blanchard, O. (2006). European Unemployment. Economic Policy Journal, pp. 7-59. • De Grauwe, Paul (2006). Economics of Monetary Union. 6th edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford • European Central Bank (2004). The Monetary Poly of the ECB. ECB, Frankfurt. • European Commission (2006). Annual Report on the Euro Area – 2006. Directorate General for Economic and Financial Affairs. • Schadler, S. et al (2005). Adopting the Euro in Central and Eastern Europe. Challenges of the Next Step in European Integration. IMF Occasional Paper 234. • Zestos, George K. (2006). European Monetary Integration. The Euro. Thomson south-Western, London 3 1. European Macroeconomic Policies 1.1. Brief Revision of European Monetary Integration Bretton Woods Regime (fixed exchange rates) • Stable exchange rates, but adjustable – – – – US dollar fixed in terms of gold ($35 an ounce) fixed parity for other currencies in terms of dollar band around dollar parity: plus or minus 1.0 % adjustment of parities after consultation with the IMF • adjustments discouraged, allowed in case of serious balance of payments disequilibria, postponed by IMF loans – Central Banks of member countries hold reserves in gold or dollars – and have right to sell dollars for gold to Federal Reserve 5 Bretton Woods Regime (fixed exchange rates) • Consequences – dollar becomes the international currency (international dollar standard or gold exchange standard) – dollar takes on role of reserve currency (interest bearing) – Central Banks must intervene in foreign exchange markets to stabilise the exchange rate of their currencies by buying and selling dollars 6 Problems of B-W regime • Problem 1: Nth Currency Problem – two currencies means one exchange rate • (N currencies mean N-1 independent exchange rates) – both countries cannot independently fix the exchange rate. – EITHER both co-operate (symmetric solution) – OR one follows a policy of “benign neglect” (asymmetric solution). Role played by the USA • Problem 2: Realignments – definition: changing the exchange value of a currency. – rendered difficult by the rules of the regime – postponed as much as possible. – Result: 7 Problems of B-W regime • Problem 3: Speculative attacks – Exchange rate value loses credible – Massive sales (normally) or purchases of the currency. • Breakdown of Bretton-Woods regime – Inflation rises in the United States of America • accelerates because of expansionary monetary policies (Vietnam war) fiscal and – Two effects • Purchasing power value of US$ falls • Other countries “import” American inflation. (see further) – Markets start selling dollars in large quantities – Movement started by request of the Banque de France (de Gaulle) to USA to convert its dollar holdings into gold (“exorbitant privilege”). 8 Problems of B-W regime • Breakdown of Bretton-Woods regime (cont’d) – August 15th 1971. Nixon closes “gold window” – December 1971. Smithsonian Agreement: general realignment and increase of band to plus or minus 2.25% – March 1973: free floating – Strong fluctuations of European currencies against the dollar – and, therefore, even stronger fluctuations between the European currencies – 1976: Jamaica Agreements (official end to BrettonWoods period) – In this context, the European Monetary System (EMS) is born. 9 First Steps Towards European Monetary Integration • Establishment of the European Payments Union (EPU) with effect from July 1950. • Principal purpose of EPU: facilitate payments for trade in goods between the OEEC member countries in a world where currency convertibility was still an issue. • The EPU was a clearing union that replaced the existing agreements by a multilateral settlement and credit mechanism: – bilateral claims and liabilities for each country were consolidated on a monthly basis in a single net position which defined the balance of payments situation of the country vis-à-vis the rest of the EPU countries. 10 First Steps Towards European Monetary Integration • Settlements could occur by payment in gold or dollars, or by automatic credit limited by quotas. • EPU set up to allow OEEC countries to liberalise trade in goods during the transition to currency convertibility. • Eichengreen (1993): immediate introduction of currency convertibility would have required large devaluations in addition to the currency realignments of 1949 and a consequent immediate loss in real income. Introduction of EPU avoided this, and gave member countries the time to redeploy their economies before rendering their currencies fully convertible. Without the EPU, multilateral trade in goods would have been endangered. 11 First Steps Towards European Monetary Integration • The Shuman Declaration of May, 9th 1950 • The Treaty of Paris signed in April 1951 established the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) • Common market for the two commodities, eliminating tariffs and quotas between the six member states 12 First Steps Towards European Monetary Integration • Messina Conference (Sicily) in June 1955 – possibility of establishing a Customs Union was studied • On March 25th 1957 two more treaties were signed – European Economic Community (EEC) and the European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM) 13 First Steps Towards European Monetary Integration • On 1 January 1958, the Treaty creating the European Economic Community (EEC) took effect. • Monetary matters were one of the least concerns in the Treaty. Exchange rate policies came under the jurisdiction of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). • The Treaty did require that the Member States of the newly formed EEC follow economic policies which were compatible with the Brettton-Woods commitments: - currency convertibility, - stable nominal exchange rates, and - liberalisation of capital markets “to the extent necessary to ensure the proper functioning of the common market” (Article 67, EEC); 14 First Steps Towards European Monetary Integration • and with fundamental economic policy objectives (balance of payments equilibrium, high level of employment and a stable level of prices). • The Treaty also required of the Council of Ministers of the Member States that they ensure the coordination of the general economic policies of the Member States (Article 145). • The general rules regarding economic and monetary policies were laid down in Articles 104 to 109 and for the liberalisation of capital movements in Articles 6773. • A Monetary Committee was created with a purely advisory role. 15 First Steps Towards European Monetary Integration • One event in this period is telling: the German revaluation of 1961, but its lessons were not learnt when the Maastricht revision of the Treaty was undertaken. • Germany was subject to inflationary pressures both on account of a high level of domestic demand and large surpluses in the balance of payments current account. • A restrictive monetary policy on its own would have led, and did lead, to an increase in capital inflows and in inflationary pressures. • It also resulted in an excessive squeeze on domestic demand. • A revaluation of the currency was not encouraged by the IMF nor by certain domestic authorities. • The German central bank, the Bundesbank, did not have the authority to revalue the currency which was a competence of the Federal Government. 16 First Steps Towards European Monetary Integration • In the end, the Bundesbank was obliged to stop its restrictive monetary policies, • and a revaluation of the Deutsche Mark occurred. • The conflict between internal and external balance could have been avoided to a large extent • if both monetary and exchange rate policies had been under the same authority. • But is this politically feasible?. 17 First Steps Towards European Monetary Integration • Meeting of Heads of State or Government of the EEC at the Hague in December 1969 • Requests Council of Ministers to draw up a plan by stages for creation of an economic and monetary union. – task proves difficult because of opposing “economist” and “monetarist” views. • “economists”: first a high degree of convergence in economic fundamentals and policies; • “monetarists”: rapid introduction of a monetary 18 union followed by economic convergence First Steps Towards European Monetary Integration • Creation of Werner Commission in March 1970 to address the issue. • Werner Report (October 1970) – complete liberalisation of capital flows – monetary union = irrevocable fixing of exchange rates – community system of national central banks – centralised economic policy – to be achieved in 3 stages completed by 1980 • compromise between “economist view” and “monetarist 19 view” First Steps Towards European Monetary Integration • Werner project endorsed by European Council in 1971 but... was overtaken by events • The Marjolin Committee declared the project dead in 1975 • The Snake (in the Tunnel) – block floating between March 1973 and Dec. 1978 – tunnel between April 1972 and March 1973 – members change frequently and realign frequently – snake lasts till 13 March 1979 upper intervention point (+2.25%) (sell $) dollar parity lower intervention point (- 2.25%) (buy $) 20 Creation of the European Monetary System (EMS) • 13 March 1979: EMS comes into existence • Result of initiative taken by Roy Jenkins in Oct. 1997 and followed up by Helmut Schmidt (German Chancellor) and Valéry Giscard d’Estaing (French President) • Based on a European Council Resolution dated 5 December 1978 • Main characteristics and operating procedures contained in an Agreement Between [all] the Central Banks of the Member States of the EEC. • Defined a system of fixed but adjustable exchange rates between participating countries. 21 How EMS addressed BrettonWoods Regime Problems • Asymmetry – introduction of ECU • a basket of currencies of all Member States • each currency in the basket assigned a weight –the weight could change over time • replaced European Unit of Account 22 The ECU A basket of all EC currencies Belgian franc = Belgian (3.301) and Luxembourg (0.13) franc 23 How EMS addressed BrettonWoods Regime Problems • Asymmetry (cont’d) – introduction of an Exchange Rate Mechanism • participation in ERM not obligatory • each participating currency assigned a (bilateral) central parity with respect to each of the other participating currencies (defines a parity grid ) • maximum variation of 2.25% on either side of central parity allowed – Italy granted exception of 6% on either side. 24 How EMS addressed BrettonWoods Regime Problems • Asymmetry (cont’d) – obligatory and unlimited intervention at the margin • suppose 1 DEM equalled 20 BEF (central parity) • market exchange rate could vary between 19.55 and 20.45 BEF • if market rate reached either bound, both the Belgian National Bank and the German Bundesbank had to intervene in the market 25 How EMS addressed BrettonWoods Regime Problems • Asymmetry (cont’d) – obligatory and unlimited intervention at the margin (cont’d) • if the exchange rate rose to 20.45 (appreciation of mark and depreciation of franc) • the Bundesbank and the Belgian National Bank would have to sell marks and buy francs • German Bundesbank at an advantage because it could print as many marks as it needed • Belgian National Bank at a disadvantage because it had a limited stock of marks to sell. • Why oblige both to intervene? 26 How EMS addressed BrettonWoods Regime Problems • Asymmetry (cont’d) – obligatory and unlimited intervention at the margin (cont’d) • because as a result of the intervention, the German money supply increased and the Belgian money supply decreased • German interest rates fell and Belgian interest rates rose, stabilising the exchange rate 27 How ERM addressed BrettonWoods Regime Problems • Realignment – At the request of one or several countries participating in the ERM, a consultation occurred involving the Ministers of Finance and the Governors of the Central Banks of all the participating countries. – These decided whether and to what extent a realignment should take place. – Consequently, realignments were carried out rapidly and with the agreement of the participating countries. – The consultation often limited the extent of the realignment out of fear of loss in competitiveness. 28 How ERM addressed BrettonWoods Regime Problems • Speculative Attacks – obligatory and unlimited interventions by the two Central Banks whose currencies were involved – markets would then know that between them the Central Banks would not run out a currency – this would reduce the probability of a speculative attack 29 Functioning of ERM of EMS • Four phases in the functioning of the ERM – March 1979 to March 1983 • Participating countries going there own way policy-wise. 7 realignments. – April 1983 to January 1987 • Participating countries beginning to recognise the constraints on policy imposed by the ERM. 4 realignments. – February 1987 to September 1992 • The “hard” EMS. 1 “technical” realignment (Italy). – October 1992 to end 1998 • the period following the “breakdown” of the EMS and preceding monetary union 30 Functioning of ERM of EMS • Four phases in the functioning of the ERM 31 Functioning of ERM of EMS Inflation 18 France 16 Germany 14 Italy 12 Netherlands 10 8 6 4 2 0 1950-1972 1973-1978 1979-1985 1986-1991 1992-1998 32 Functioning of ERM of EMS • Why did the ERM “break down” in Sep. 1992? – Remote causes • the system had become too rigid – markets convinced no more realignments before monetary union (Delors effect) • loss of competitiveness of certain countries • large capital flows into high interest rate countries (Italy, Spain and Portugal) – is this compatible with interest rate parity? – risk premium. 33 Functioning of ERM of EMS • Why did the ERM “break down” in Sep. 1992? – Remote causes (cont’d) • the system had become asymmetric and dependent on Germany – the Bundesbank set the interest rate for Germany – the other ERM countries tied their currencies to the German mark – the other ERM countries adapted their interest rate to Germany’s » In the ERM, Germany played the role that the USA played under BrettonWoods 34 Functioning of ERM of EMS • Why did the ERM “break down” in Sep. 1992? – Proximate causes: • capital flows (liberalisation of capital flows in 1990) • the Bundesbank hikes up its interest rate after reunification • Maastricht Treaty vote in Denmark and in France • Solution: either floating exchange rates or move to monetary union » Britain chose floating » as did Italy and Spain temporarily – fluctuation margins increased to 15% on both sides of central parity 35 Functioning of ERM of EMS • “Impossible or Incompatible Trinity” – independent monetary policy • that is, achieve an internal target – fixed exchange rates • that is, achieve an external target – free movement of capital One of these three goals must be given up. 36 Transition to a Monetary Union • The Delors Report • The Maastricht Treaty – The 3 stages – Stage Two: preparing for monetary union • establishment of the European Monetary Institute • countries shall endeavour to avoid excessive fiscal deficits • the criteria for membership – Stage Three: monetary union 37 Criteria for membership 1. The government deficit may not exceed 3% of Gross Domestic Product at market prices. If it does, the Commission must take into account whether it has declined substantially and continuously or the excess is temporary in nature. Furthermore, it must examine whether the deficit exceeds expenditure on investments as well as certain other elements 38 Criteria for membership (cont’d) 2. Government debt may not exceed 60% of Gross Domestic Product. If it does, the Commission should take into account - whether the ratio is diminishing sufficiently and - approaching the reference value at a satisfactory speed. 39 Criteria for membership (cont’d) 3. The inflation rate is sustainable and, over the year preceding examination, does not exceed by more than 1.5% that of, at most, the 3 best performing Member States. The consumer price index shall be used 40 Criteria for membership (cont’d) 4. Long term interest rates (on long-term government bonds or comparable assets) shall not exceed, over the year preceding examination, by more than 2% that of, at most, the 3 best performing Member States in terms of inflation rates. 41 Criteria for membership (cont’d) 5. The Member State - shall have participated in the ERM of the EMS and - respected the normal fluctuation margins without severe tensions for at least two years before the examination. It shall not have devalued its currency against any other Member State's currency on its own initiative for the same period. 42 Criteria for membership (cont’d) Some authors also add a legal convergence criterion, i.e., the countries legislation should conform to the Treaty in matters such as central bank independence and the ESCB Statute. 43 Transition to Membership • Public finances consolidation – EMU as deflationary? or stock adjustment? • Exchange rate mechanism • Real convergence – not included in Maastricht Treaty criteria – was not a problem for “old” Member States – but may be one for new Member States 44 The Path of the Euro 45 1.2. Recent Macroeconomic Developments in the Euro Area 1.2. Recent Macroeconomic Developments in the Euro Area • Following Relative mild downturn in 2001-2003, the euro-area economy experienced a comparatively slow recovery • In 2006 economic growth is expected to accelerate (EC Commission forecast – 2.6 % increase in GDP for 2006) with countries like Finland, Greece, Spain, Ireland and Luxembourg growing more than 3 %. 47 1.2. Recent Macroeconomic Developments in the Euro Area • The euro-area’s economic recovery is underpinned by a strengthening of domestic demand, particularly investment • Total Investment is expected to grow by 4.2 % • This is due mainly to historically low interest rates, improved corporate balance sheets • The Outlook for consumption in the Euro Ares in 2006 is for a modest upturn – 1.7 % increase 48 1.2. Recent Macroeconomic Developments in the Euro Area 49 1.2. Recent Macroeconomic Developments in the Euro Area • The euro-area’s economic recovery is also being helped by the continued strong expansion of world output and trade • World GDP at 4.6 % (strong overall performance in China, India, Japan and USA) • World trade growth in 2006 is expected to be around 8% - with EU exportsto the rest of the world growing by 5.5% 50 1.2. Recent Macroeconomic Developments in the Euro Area 51 1.2. Recent Macroeconomic Developments in the Euro Area • The European Commission expects consumer price inflation to remain at 2.1% in the euro area in 2006 • Core inflation (CPI excluding energy and unprocessed food) continued to decline and stood at 1.5% in May 2006 • Oil prices have recently reached record high levels of 70 USD per barrel of Brent crude oil. • According to Commission estimates price per barell in 2006 will average 68.9 USD (27.4% increase compared to 2005). Effect on Euro area CPI should be moderate (see box 1.1) 52 1.2. Recent Macroeconomic Developments in the Euro Area 53 1.2. Recent Macroeconomic Developments in the Euro Area 54 1.2. Recent Macroeconomic Developments in the Euro Area • Potential risks to continued investment growth in the EU: • Further increasing oil prices • The impact of the budgetary consolidation in Germany (increase of VAT from 16% to 19%) – German households may bring forward some purchases of durable consumer goods. Hence German GDP is expected to fall slightly in 2007 55 1.3. Macroeconomic Policy Settings 1.3. Macroeconomic Policy Settings • The overall aim of macroeconomic policy in the euro area is to keep output close to potential, whilst preserving price stability. • In the medium term: minimization of uncertainty of households and businesses about future macroeconomic policies; stimulating consumption and investment decisions • The short term responsiveness of policies is essential as economic circumstances change continuously. 57 1.3. Macroeconomic Policy Settings • Monetary conditions: Monetary policy has helped to spur economic activity and promote confidence through historically low nominal and real interest rates. • Recent increases should help to anchor medium- to long-term inflation expectations (see graph 2.2) • Interest rates are very low from historical perspective – the lowest interest rate ever attained by the German Bundesbank (BuBa) was 2.5% 58 1.3. Macroeconomic Policy Settings 59 1.3. Macroeconomic Policy Settings • Inflation rates have stayed close but above the ceiling of 2 per cent. • Long-term inflationary expectations are below 2 % (see graph 2.4). • The euro-area’s economic recovery has coincided with a remarkable degree of wage moderation (due to the behavior of social partners): Low wage growth can help to reduce inflationary expectations. • On the contrary – high inflationary expectations lead to high inflation and may jeopardize the economic recovery. 60 1.3. Macroeconomic Policy Settings 61 1.3. Macroeconomic Policy Settings • Fiscal Policy: Fiscal policies remain the responsibility of individual member states, but there are some general requirements set in the EC Treaty and in the SGP. • Member states can make e positive contribution to economic growth by improving the quality if their public finance. • The euro area is already burdened with too high level of debt (see graph 2.8) 62 1.3. Macroeconomic Policy Settings 63 1.3. Macroeconomic Policy Settings • Another reason to improve the sustainability of public finances is the additional budgetary pressure that will stem from the ageing of the euro-area’s population (see graph 2.9). • Change of the old-age dependency ratio • Pressure on public finances • Conclusions: EMU’s policy framework has contributed to a very favourable macroeconomic policy mix. 64 1.3. Macroeconomic Policy Settings 65 1.4. The External Dimensions 1.4. The External Dimensions • Since its launch in 1999, the euro has become the second most important international currency, behind the US Dollar. • In the first half of 2006, the euro appreciated against the US dollar and the Japanese Jen, having depreciated in both cases in 2005 (see graph 4.1) • Interest rate differentials (see graph 4.3) and global imbalances (see graph 4.4) will play a role in determining whether there will be continued appreciation of the euro or a further dollar strength. 67 1.4. The External Dimensions 68 1.4. The External Dimensions 69 1.4. The External Dimensions In 2005 US posted the largest current account deficit of its history - 6.4 % of its GDP Due to persistent differences in saving and investment behavior in US. Although the euro area has a roughly balanced current account, it would not be immune to effects of a disorderly correction in global imbalances. 70 1.4. The External Dimensions 71