Subjective Versus Objective Welfare: Poverty in Palanpur

advertisement

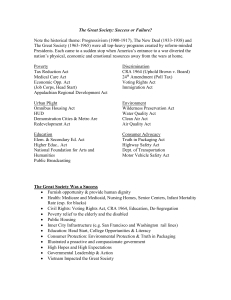

Peter Lanjouw, DECPI Michael Lokshin, DEPI Zurab Sajaia, DECPI Roy vand der Weide, DECPI With Professor James Foster (GWU) Module 4, Feb 28-March 1, 2011 Monday Feb 28 Session 1 (Peter Lanjouw): 9:00-11:00 ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ Opening Remarks and Introductions Concepts, Definitions and Data Constructing a Consumption Indicator: Adjustments for Family Composition and Size Session 2 (Michael Lokshin): 11:15-12:30 Session 3 (Michael Lokshin and Zurab Sajaia): 2:00-3:30 ◦ Poverty Lines ◦ Poverty Measures: Properties and Profiles ◦ ADePT Software for Poverty Analysis Tuesday, March 1 Session 4 (Roy van der Weide): 9:00-10:30 ◦ Statistical Inference and Poverty Decomposition Session 5 (Professor James Foster): 10:3012:00 ◦ New Frontiers in Poverty Measurement I Multidimensional poverty measurement Chronic versus transient poverty Session 6 (Peter Lanjouw): 2:00-3:30 ◦ New Frontiers in Poverty Measurement II Small area estimation of poverty Making non-comparable data comparable Developing pseudo-panel data for poverty comparisons What do we mean by “poverty”? Common definition: More narrow definition: Less narrow definition: ◦ Lack of command over commodities; “..a severe constriction of the choice set [over commodities]” (Harold Watts) ◦ Lack of specific consumptions (e.g. too little food energy intake; too little of specific nutrients; too little leisure.) ◦ Poverty as lack of “welfare” e.g., lack of “capabilitiy”: inability to achieve certain “functionings” (“beings and doings”) (Amartya Sen) Other important definitions Consumption: destruction of goods and services by use Expenditure: consumption valued at prices paid (whether or not there was an actual transaction) Income: maximum possible expenditure on consumption without depleting assets Often used interchangeably, but beware! 1. Poverty data can inform, and misinform, anti-poverty policy. The growth strategy Has poverty increased? Did growth help the poor? How did relative price changes affect the poor? What is the impact of food price fluctuations? Who were the losers and who were the gainers from economywide policy reforms? (ex-ante versus ex-post) 2. Social Spending Who uses public services? At what cost? Who benefits from government subsidies? On average, versus at the margin? Who will be hurt by retrenchment? 3. Targeted Interventions Who are the target groups? How should transfers be allocated? How much impact will they have on poverty? How do we measure “welfare”? When do we say someone is "poor"? How do we aggregate data on welfare into a measure of “poverty”? How robust are the answers? Common practice emphasizes economic welfare: ◦ add up expenditures on all commodities consumed (with imputed values at local market prices) and ◦ deflate by a poverty line (depending on household size and composition and location/date) “real expenditure” or “welfare ratio” Survey data Differ according to: ◦ - the unit of observation (household/individual), ◦ - no. observations over time (cross-section/panel); ◦ - living standards indicator (consumption/income) Survey design Does the sample frame cover the entire population? Is there a response bias? What is the sample structure (clustering, stratification)? Goods coverage and valuation Is the goods coverage comprehensive? Is the survey integrated (e.g. price analysis)? Are there valuation problems? Variability and the time period of survey Is there significant variability over time? Can this be encompassed within the recall period? What are the implications for the choice between consumption and income? Inter-personal comparisons Is consumption a sufficient statistic? What other variables matter? (Prices, demographics, publicly provided goods) Income per capita Consumption per equivalent single adult Food-share ("Engel's Law") Nutritional indicators ◦ Poor indicator when incomes vary; hard to measure ◦ Problems with forming scales; composition versus size economies; intra-household inequality. ◦ Sources of noise: other parameters; problem of income elasticity near unity. Identification problems. ◦ "Welfarist" critique (welfare and nutrition are different things); nutritional requirements/ anthropometric standards. Anthropological methods ◦ Concerns about representativeness and objectivity; lack of integration with other methods. We can learn a lot from case studies, but they don’t represent a whole country. Subjective/qualitative methods ◦ Can provide useful extra information – to help solve the identification and referencing problems. Use a comprehensive consumption measure, spanning consumption space Choice between income and consumption is largely driven by the greater likelihood of accuracy of information on consumption. Recognize the limitations of consumption based measures; look for supplementary measures, esp access to public services, subjective welfare, for complementary insights. The consumption measure serves as the foundation upon which much of the subsequent poverty analysis rests. Principles ◦ Should be comprehensive ◦ Retain transparency and credibility ◦ Goal is to be able to rank individuals credibly in terms of welfare Construct a food consumption measure Add basic non-food items (from consumption module) Add other non-food items (other modules) Add housing expenditures Add use-value of consumer durables Surveys typically ask about food consumption, item by item, over a specific reference period. ◦ In general, the longer (and more disaggregated) the list of items, the higher is food consumption Sometimes information is asked about consumption in a typical reference period (e.g. month). ◦ This has the attraction of helping to overcome seasonality concerns. Surveys vary in terms of recall periods ◦ Some surveys use diary methods rather than recall periods. We expect that the longer the reference period, the more expenditures are likely to be biased downwards (recollection difficulties) But, the shorter the reference period, the noisier are the expenditure data. ◦ This can hamper poverty comparisons. Food expenditures should include not only purchased items but also consumption out of home production. ◦ Home production should be valued using local market prices (preferably farm-gate) Most surveys record not only food expenditures, but also quantities ◦ This information is of use for the construction of poverty lines ◦ When dealing with separate price, quantity and frequency information, on an item by item basis, one often needs to impute certain missing values. The typical consumption module includes a range of non-food items alongside food. Other parts of the questionnaire may also include certain non-food expenditures (housing section, education and health sections) Key issue is to distinguish between investments and consumption (avoid double counting). Health expenditures are usually excluded ◦ Lumpy ◦ If we include we should also have a good measure of need. Two Additional omissions: ◦ Leisure ◦ Public goods The problem is essentially one of pricing: ◦ Should we value an unemployed person’s leisure based on wages in a market to which the individual has no access? ◦ What is the value to individuals of publicly provided goods? Imputations for public goods and leisure are likely to compromise credibility and usefulness of welfare measures. ◦ We should still document who gets public services, or is unemployed, and examine whether these are poor or rich. In most settings a minority of households rent their dwelling, and a majority reside in their own homes. Home-owners consume a stream of services from their homes. This is precisely what rentors pay for with their rent. The challenge is thus to impute for home-owners what they would be paying in rent if they were renting rather than owning their house. Many surveys ask specifically what a household would pay in rent if it were renting. Where credible this number can be used for home owners. Elsewhere one can try to predict rent paid based on regression models estimated on subset of renting households. Purchases of irregular, lumpy items such as consumer durables (tv, car, etc.) cannot be directly added to the consumption definition. ◦ Many households are unlikely to make such purchases within the reference period of the survey. ◦ But many will be consuming a stream of services from those items that they own. Surveys often solicit information on the age of assets owned, original purchase price, and current replacement price. Based on this information it is possible to calculate the consumption stream of services from the durable as: ◦ Consumption Stream = Current value*(real interest rate + depreciation rate). The Headcount With Alternative Consumption Aggregations Consumption Aggregate Ecuador Nepal Brazil Food Spending plus Basic Non-Food Spending 1.00 1.00 1.00 Food plus Basic Non-Food Spending Including Energy and Education Spending 0.85 0.91 0.89 Above With Actual or Imputed Water Expenditures 0.81 n/a n/a Above With Actual or Imputed Value of Housing Services 0.70 0.77 0.65 Above With Imputed Value of Owned Consumer Durables 0.68 0.76 n/a Do not compare Apples with Oranges!!! Figure 1a. Poverty headcount rate (%) at $1.25/person/day by module type 66.8 62.8 64.6 59.5 54.9 55.6 55.1 47.5 1. Recall: Long, 2. Recall: Long, 14 day 7 day 3. Recall: 4. Recall: 5. Recall: Long Subset, 7 day Collapse, 7 day Usual 12 month 6. Diary: HH, 7. Diary: HH, 8. Diary: Frequent Infrequent Personal 24 Ultimate goal is to arrive at a money metric of individual welfare. Consumption (and income) aggregates are usually constructed at the level of the household. Convention is to divide household consumption by the number of family members to arrive at a measure of per capita consumption. This approach sidesteps two issues: ◦ Different people may have different needs ◦ The cost per person of reaching a certain welfare level may be lower in large households than small ones. In principle equivalence scales can be used to adjust for differences in needs. ◦ E.g. If a child needs half as much as an adult, then a two adult - two child household will consist of three equivalent adults. ◦ If the total consumption of household is 120 then equivalent-consumption will equal 40. All four individuals will be allocated this equivalent-consumption. Where do equivalence scales come from? ◦ Huge range of candidate scales Nutritional scales – derived from health studies. At best can be used to deflate food expenditures. Behavioral scales – econometric estimates based on observed allocations. Major difficulties with identification. For example, if we observe that female children get less, do they need less? Or is it that they are systematically discriminated against? Little guidance as to which scales are best. One option to conduct sensitivity analysis. (India example) The head-count ratio and equivalence scales Household Type Equivalence scales (1,1,1) (1,1,0.6) (1,0.8,0.6) (1,0.7,0.4) All households 63.4 63.2 62.9 63.8 Male-headed 63.8 63.6 63.5 64.5 Femaleheaded 57.7 57.4 54.3 52.7 Widow-headed 58.3 61.9 58.2 58.6 Extended; male-headed 68.2 69.5 67.6 67.4 Source: Drèze and Srinivasan (1997), Table 3. Note: The equivalence scales are written as triplets indicating the weights for ‘adult male’, ‘adult female’ and ‘child’, in that order. We often find that poverty profiles do not change much as a result of equivalence scale adjustments. Use of per capita welfare measure may not be too misleading This is an empirical question that needs to be checked on a case-by-case basis. The use of a per capita measure of consumption imposes an assumption of no economies of scale in consumption. Where might such economies come from? ◦ Consumption of public goods within the household (radio, water pump) ◦ Bulk purchase discounts on perishable food items ◦ Economies in food preparation (fuel, time) Suppose money metric of consumer’s welfare has an elasticity of θ with respect to household size. Then welfare measure of a typical member of any household is measured in monetary terms by: x x n * Suppose that ρ is the proportion of household expenditure on purely private goods, and 1- ρ is allocated to public goods. Then the correct monetary measure of per-capita welfare is: x x ( ) (1 - ) x n n Solving for θ yields: - ln( 1 - ln( n) n ) In Ecuador, average household size is 4.76. ◦ If ρ =0.9 then θ=0.8 ◦ If ρ =0.7 then θ=0.51 If average size = 6 ◦ ρ =0.9 then θ=0.77 ◦ ρ =0.7 then θ=0.49 Problem, as with equivalence scales, is that there isn’t a good way of estimating θ Best bet is sensitivity analysis again. (India Example) The head-count ratio and economies of scale Household Type Mean size Economies of scale parameter θ 1 0.8 0.6 0.4 All households 5.35 63.4 59.6 54.5 49.5 Maleheaded 5.56 63.8 59.4 53.9 48.6 Femaleheaded 3.60 57.7 61.6 62.0 62.6 Widowheaded 3.32 58.3 63.8 65.1 66.2 Extended; maleheaded 6.78 68.2 60.3 51.0 43.5 Source: Drèze and Srinivasan (1997), Table 4. Message now is that the per capita assumption is not innocuous. Conclusions as to the relative poverty of large households (many children) versus small (elderly) are usually quite sensitive. ◦ Big issue in regions (ECA) where there are big debates regarding public spending priorities (pensions versus child benefits) ◦ Note, over time, economies of scale parameters could evolve (Lanjouw, et al, 2004) Martin Ravallion, Poverty Lines in Theory and Practice, Living Standards Measurement Study Working Paper 133, World Bank, Washington DC., 1998. Martin Ravallion, "Issues in Measuring and Modeling Poverty", Economic Journal, Vol. 106, September 1996, pp. 1328-44. Martin Ravallion, Poverty Comparisons, Fundamentals of Pure and Applied Economics Volume 56, Chur, Switzerland: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1994. Beegle, K., De Weerdt, J., Friedman, J., and Gibson, J. (2011) ‘Methods of Household Consumption Measurement Through Surveys: Experimental Results from Tanzania’ Policy Research Working Paper No. 5501, the World Bank. Hentschel and Lanjouw (1995) ‘Aggregating Consumption Components and Setting Demographic Scales: Implications for Measured Poverty in Ecuador’, mimeo, DECRG. Lanjouw, J. and Lanjouw, P. (2002) How to Compare Apples and Oranges: Poverty Measurement Based on Different Measures of Consumption, Review of Income and Wealth 47(1), 25-42. Deaton, A. and Zaidi, S. (1999) ‘Guidelines for Constructing Consumption Aggregates for Use as a Money-Metric Welfare Measure’, LSMS working paper No 135. Deaton, A. and Paxson, C. (1998) Economies of Scale, Household Size and the Demand for Food, Journal of Political Economy, 106(5): 897-930. Lanjouw, P.F. and Ravallion, M. (1995): Poverty and Household Size, Economic Journal, Vol 105, No. 433. Lanjouw, J., Lanjouw, P., Milanovic, B., and Paternostro, S. (2004) Economies of Scale and Poverty: the Impact of Relative Price Shifts During Economic Transition, Economics of Transition 12(3) 509-536.