Are we yet at the point where videogames are seen as a

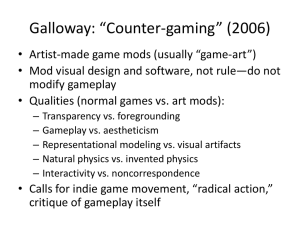

advertisement

BA(HONS) 3D GAMES ART & DESIGN – LEVEL 3 Are we yet at the point where videogames are seen as a sophisticated form of art and entertainment? How the way in which we deal with gameplay and narrative sequences is currently holding back game creation By Colin Ross Word Count: 5553 Lecturers: Dr Ivan Phillips & Arlene Hui ‘Submitted to the University of Hertfordshire in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts (Honours), April 2009’ Are we yet at the point where videogames are seen as a sophisticated form of art and entertainment ? How the way in which we deal with gameplay and narrative sequences is currently holding back game creation Introductio n The design of videogames has always inspired me from early age from when I first grasped my hands on a Binatone TV M aster game controller. That memory is not exactly vivid, but I remember it being a moment where I was interacting with an interface which to me at the time gave me the impression I was playing tennis. My young brain was enthralled w ith somehow I was affecting what was happening on the TV, inside a TV (I must of been 4 -5 years old). This was eno ugh, I was hooked; that moment I'll never forget. At the time I didn't see it as the simple game of Pong, to me it was much more than a 2x8 pi xel paddle and a 4x4 pixel representation of a ball rendered in glorious black and white. It is one of the simplest games ever created but from that moment there has led me on to now having a passion and a desire to create, entertain and progress the way g ames are made and hopefully fo r others to enjoy those moments like my own in the future when playing a videogame. As with other forms of media like films, books and even music, videogames strive to hit a personal note with the consumer. In this case wanti ng the media to change peoples lives or to genuinely be important to them. Other forms of media are able to do this, and you’ll often hear people explain abo ut a past experience with either a book or a movie and that piece of media that has stuck with them for many years. In my opinion t he games industry is still struggling with this even now, and really this way of looking back at a piece of work can only be specific for people who actually work in the industry or that are more looking at the work on a professional game design level, and this is more of a cold mechanical way of the piece of work reso nating and not the warm life changing effect we should be desiring which other media pulls off so well. In a way this can be brought back to the fact that this medium is still in its infancy. Games are still not looked at in the same light by the mass as an accepted form of entertainment where a piece of work can be looked at and be held up high. I feel we are no w getting to the point where this is being questio ned more and more so by both the audience and game makers and people’s stance is starting to change on this and how they see the medium . Videogames themselv es have always struggled to gain acceptance along with other forms of media like music, literature and film, and we’v e always been 2 used to this form of entertainment having an aura of curiosity to those who aren’t familiar with it or who dismiss it as purely a recreational past -time. Things are changing gradually though and when I overhear co nversations about elderly people being interested or playing videogames like Nintendo’s Wii Sports or Dr Kawashima’s Brain Training then it makes me realise that this form of entertainment is slowly going to be accepted by all just like cinema for example has in the past. Or am I just jumping ahead here ever so slightly? Barry Atkins also feels that the medium doesn’t get treated like it should by all tho se parents and you could say ‘outsiders’, who’ve never dared to even pick up a game controller because they feel this medium isn’t actually that sophisticated. To quote his book ‘More Than a Game’, ‘Th a t th e co mp u t e r g a m e h a s n ot, to d a t e, r e ce i v ed mu ch s er iou s cri ti ca l att en tion a s an in d ep e n d e n t for m o f fi c tion a l exp r es s ion , rat h e r th an in p a ss in g a s a t e ch n o log ic al cu r io sit y or a s a sp rin gb oard fo r so m e ext r e me l y sp e cu la ti v e t h e ori s in g ab ou t th e p os s ib i lit i e s th a t mi gh t on e d ay b e r e v ea l ed in vi rtu a l r e ali ty o r cy b e r s p ac e i s h ard ly su r p ri s in g , h o w e v er. I f t h i s i s a f or m o f f ict ion , t h en it is sti ll p e rc e i ved as a for m of fi ct ion fo r ch ild r en an d ad ol e sc en t s, wit h al l th e p ejo rat i v e a s so cia tio n s th at su ch a cla s s if ic ati on car ri e s wi t h it. G a me s, with th ei r v ast ti m e d e man d s an d la ck o f d i sc er n ib le p rod u ct i n th ei r n ea r - on an i sti c en ga ge m en t o f a n in d i v id u a l wi th a m ac h in e, h a v e h ard l y b e en w el co m ed wi th op en a r m s b y th e p ar en t s of t h e ir tar g et au d i en ce . ‘Ad u lt’, wh e n it is in vo ke d a s a t er m a t all, m o st o ft en eq u at e s wi th ‘p o rn o gra p h i c’, rat h er th an ‘sop h i st ic at ed .’ [ 1 ] I feel that videogames as a form of entertainment are still lacking in way stories are told, and that we’ve yet to get to the point where videogames have a syllabus to define gameplay, fun and the mechanics which are used . This essay will attempt to take on the subject on two fronts. One being from the perspective of how narrative is conveyed during a game and with that my opinio n of it being co nflicted with gameplay actions; with this I will also attempt to look at pieces of work that may have an answer to these pro blems as well as stepping stones which I feel are progressing the industry in the way we convey our narratives with actions . My second front of tackling the subject will involve why videogames are still lo oked up on as not being as sophisticated as a form of entertainment along with film, music and other mediums. My opinion is that these two fronts are linked, with our stories and interaction still holding us back. 3 Why gameplay & narrative tend to be conflicte d The work needs to be meaningful and important, and try to avoid the fake unimportant careless decisio ns that pull the user out of the experience and makes them question why that choi ce was made in the first place. I personally feel that video games need to start playing to their strengths more. This is a medium which is a mash up of various other forms of media, like having visual elements, text, and also music. Maybe more focus back to the actual ‘gameplay’ which is a trait no other medium has would be a n advantage and a unique way to then touch peoples lives. With videogames we have at least two ways in which we can make the piece of work be important to people. I feel the most important two ways are by expression or by an introductio n of an activity. Ex pression in this case is what we are accustomed to when watch ing a film or a television show and an introductio n of an activity being a learning process, that when gon e back to later on is remembered . When a certain level of an activity is achieved the end user feels proficient and pleased they can achiev e something. In real life we could parallel this to an activity like learning how to play football, and while the same process of activity in a videogame could be the learning process o f how to play Namco’s Pac-Man as an example . The activity there is learning the most effective way to avoid the ghosts while also eating all the dots on the screen; this isn’t something a user can be proficient in the m oment they pick up a game pad, it’s something that takes time to achieve . Story games are co nflicted. The audience can sense a piece of conflicted work and this ends up not striking with the audience on a deep level much like books and films inherently pull o ff much better currently. What needs to be worked out is how to remove this conflict between gameplay and the story which is trying to be told. We want to move away from the process where a person playing a videogame then questions a decision he or she had to make, but really had no choice whether they sho ul d turn on or turn off the ‘hacking computer ’ as an example . It seems like a choice is given for the person playing the videogame, but in essence there was only one option anyway as otherwise they couldn’t progress and neither could the narrative . I personally could not get to point where I could answer that question as to how to remove this conflict at a lower level to cover all game design (and I do ubt anyone else could currently) , but more of a desire to experiment in this industry may bring results over time. My opinion is that it’s alway s going to be a case of making ‘baby steps’ where designers are reiterating on both past design mistakes or improving upon them. Treading this new ground which we’ve yet to explore is part of the process. We don’t yet hav e set rules which need to be followed of what equals both fun and compelling gameplay or anything to define either . Tracy Fullerton is a game designer, educator and writer on v ideogames; and her article on ‘Improving Player Choices’ brings up some very i nsightful ideas. 4 ‘No matt e r wh at y ou ' ve b e en t old in th e p a st, d r ama an d su sp en s e in ga m e s s eld o m co m e fro m th e sto ry l in e. I t c o m e s fro m th e a ct o f ma k in g d e ci s ion s t h at h a ve w ei gh t, an d th e mo re w e igh t eac h d ec i si on ca rr ie s , th e mo re d ra mat ic th e ga me b e co m e s.’ [ 2 ] I feel this quote above from Tracy Fullerto n’s Gamasutra article in question cannot be taken serio usly eno ugh. Here she is explaining that the drama and how epic these stories actually become during the game are o nly ever communicated to the player thro ugh the gameplay c hoices which they have to make and the gamers actions with their choices only start to resonate because they brought the events into motion themselves and not upon a linear path where interactivity was taken away from the player. Fig 1 . Decisio n Scale Source: Fullerton, Tracy. (2004) Improving Player Cho ices. Gamasutra.com [2] Fullerton explains in the article that with the help of the ‘decision scale’ (shown in Figure 1) gameplay choices can be easily analysed. This for example could be the player choosing whether their ally in the game world lives or dies early on during the narrative, and for it then to have a consequence later on. This sort of choice would be very critical and wo uld matter to the pl ayer (which is a ‘dilemma’ choice), unlike a minor gameplay choice of choosing which weapon to equip for a boss battle for example when both weapons deal the same damage to the boss. This would be so inconsequential to the player that they needn’t even be given this gameplay choice. Why waste the players’ time with these choices when they aren’t ever going to affect the narrativ e or more importantly be remembered as an action that changed the users overall experience with the game ? With 5 having the choice of which weapon to choose currently being ‘inco nsequential’ the developer could indeed change this gameplay choice to being ‘important’ and having an immediate impact. The boss for example could be a fire breathing foe, while one weapon could protect the pla yer from such an element while the other wouldn’t, but the other weapon would enable the player to deal more damage. This initial gameplay choice now has a consequence for how the player deals with the boss battle, and the interactive narrativ e of which we apon to choose now has a reason and a substance. The reason why in a lot of narrative led games of recent years have not a bearing on Fullerton’s ‘Improving Player Choices’ scale is because typically designers go into creating a narrative first and foremos t and leaving the actual ‘game’ and interaction to be then designed aro und the already formulated plot. This then automatically brings gameplay actions that simply hold no real weight or for the action to be meaningful, and this process could then continue on in the gameplay space of a title while a narrative element is played out of which would reduce both to nothing significant to write home about. Often modern v ideogames tend to opt for telling narrative in no n interactive sequences or cut -scenes, with this in my mind shows that the overall design of the game and how the story is told could have easily been done the same using other established forms of media be it with literature or cinema. Although I understand that there are many ways to tell a story , for me I’d like to see less of the non -interactive cut -scene approach to telling stories in videogames, and more use of the medium in itself being gameplay and what videogames at the core element are through learning patterns and what our actions can be interpreted as . Games industry veteran Warren Spector, founder of Junction Point Studios, seems to agree with me here. He is known for being outspoken with regards to narrative in video games, and in a recent interview with industry magazine ‘Develop’ he pu t forward his opinion. “Wh at p a s s es f or in t er a cti on in th e ga me b u sin e s s 9 8 p er c en t o f th e t i m e i s an i llu s ion , an d th e r ea li ty i s th at w e h a v e en ou gh co mp u ti n g p o w er an d w e h a v e e n ou gh s of t war e kn o wl ed g e th at w e can actu a lly c re at e tr u e r i n t era ct ion th an w e cou ld i n th e p a st .” [3 ] Maybe his thoughts here have more substance with how technology has progressed in more recent years, but he also steps down on the v iew that game developers can do so much more with telling narrative in videogames, and like myself, I believe it co mes down to developers not attempting more creative ways of telling these stories with the available technology. He continues on explaining about choices and the player, “When I see people faking it – choices that don’t mean anything, choices that have no consequences, choices where the game will 6 keep bum ping you back until you make the right o ne – I just can’t deal with that. Really giving players power over how a story unfolds is the ultimate grail.” This obvio usly comes back to ho w gameplay choices can engage a player and push on the narrative with these choices and referencing back to the example of the ‘hacking computer’ previo usly used . I understand that now with so many genres of v ideogames being available to consumers and also with more people playing videogames than ever before that there of course should be room for all types of games and ways of telling stories, but I just hope that m ore videogames try to tell their narrative through i nteractivity and gameplay. 2K Games BioShock (2007) instead of jum ping into non -interactive sequences to tell the story opted to give the player recorded conversations on D ictaphone tapes which are littered around the game world. The player would then pick these items up with a gameplay choice if they were ever sought o ut and the tape would then automatically play while the player would then continue on their way with whatever else they were doing i nside the wo rld. This itself had nev er been done prior to the games release in any other title , and although it sounds like such a minimal idea it never drags the player out o f the experience or detracts them from it; and if anything it builds on what is already there and furthers the players absorption into the game world. The Dictaphone tapes littere d througho ut the game world were entirely optional pickups, so with this being the ‘choice’ then the player then had the option as to whether their gameplay experience involved more narrative or kept to a minimum; and ultimately the player having co ntrol o f the narrative of when and what order to receive back story to the world. This way of delivering the narrative made peoples experiences of the game rather varied where some parts of the audience may not have listened to parts of the back story that other players may of. While BioS hock was applauded for its decisio ns on how to tell its narrative to the player, some gam es can’t have the same approach due to gameplay constraints and what would fit in their virtual world that they’ve created and especially fro m a design perspective if a narrative is constructed first of all . Warren Spector understands that there are these small steps dev elopers need to take, and I’m assu ming that the dev elopers of BioS hock are some of these people taking these small steps like he has mentioned below. “Th er e ar e b a b y st ep s w e n e ed t o tak e alo n g th e way, an d t h e r e ar e p e op l e ta kin g th os e st ep s, b u t b y an d l ar ge p eop l e ar e s til l in th e m ov i e min d s et . A s s oon a s I h ear of s crip t ed mo m en t s t h at p ro vid e in c r ed ib l e e mot ion a l p u n ch , an d a s so o n as I go o n for u m s an d re ad e v ery p er so n say i n g ‘ Wa sn ’ t it coo l wh en c h ara ct e r X j u mp ed a cr o s s 7 th at ch a s m ?’ a ll I wan t t o d o i s scr e am . I f e v ery p lay er i s d o in g e xa ctly t h e sa m e t h in g at exa ct ly th e s am e ti m e, i t’s n ot a g am e . Go ma ke a mo vi e a n d g et ou t o f my m ed i u m .” [3 ] Warren Spector’s statement backs up my feelings that although such a minimal addition to Bioshock was made with the Dictophone tapes it still enabled that non-scripted feeling where optio ns were available and no one was led down the same path througho ut their experience with the title. Dynamic stories More and more games are now attempting ‘dynamic stories’ though where more than just a linear path is there to progress, where decisions affect later choices and so on. This is expensive to do in regards to man -hours it takes to build these seemingly forev er branching webs of variables and the finances available to do so, and it also brings up the problem of when you start being dynamic narrative wise then when the limits are set for that dynamic narrative then they will also be met and pushed to their boundaries by the user. Once these boundaries and limitatio ns are met then the experience is degraded and brings back that feeling of linearity . Modern technology also gives game d evelopers many ways to tell narratives from traditional approaches. But this technology can also have the pro blem of game developers wanting to do things gameplay wise with o pen choices just because they can. This would for example bring the player further away from the narrative and overall experience. If a player can run up against a wall and just jump everywhere without any purpose while also landing nowhere of any major significance then wouldn’t this bring you the player further away from that experience? Would this idea also bring into the picture a competition between gameplay and narrative and what is vying fo r the players perceptual, cognitive and motor effort? Craig A. Lindley’s paper titled ‘Conditioning, Learning and Creatio n in Games: Narrative, The Gameplay Gestalt and Generative Simulation’ puts forward that motion, and gives an opinio n that there surely is a fine balance to achieving a unification between these elements. ‘To e xp er ien c e a ga m e a s a n ar rat i ve r eq u i r e s th e cr eat ion of a n a rra ti v e g es tal t u n ify in g th e ga m e exp e ri en ce s in to a coh er en t n ar rat i v e st ru c tu r e. Th e te n sion b et w e en g a mep lay an d n ar rat i v e c an n o w b e vi e w ed a s a co mp eti ti on b e t we en th e se r e sp e cti v e g e stal t for m ati on p r oc e s s e s for p er c ep tu al, co gn i ti v e, a n d m oto r ef fo rt. Wi th in th e ran ge o f e ff ort r eq u i r ed for i m m er s ion a n d en g ag e m en t, if ga m ep lay con su m e s mo st o f th e 8 ava il ab l e co gn it i v e r e so u rc e s, th e re wil l b e lit tl e sc op e l e ft fo r p er c ei v i n g c o mp l ex n arra ti v e p a tt ern s, an d litt l e p o in t in t er m s o f a d d in g to i m me r sio n an d en g ag e m en t . Con v er s e ly , fo cu sin g on th e d e v e lop m en t o f th e s en s e o f n a rra ti v e r ed u c e s th e p lay er s n e ed an d c ap ac ity fo r a h igh ly en g ag in g ga m ep l ay g e sta lt.’ [4 ] This brings together that attempting to tell a story in the same way as which a film general ly does will always cause problems. It’s obviously apparent that the medium of ‘videogames’ borrows heavily from other media, and in some regards mashes it all together while chucking in interactivity. Is this what we want videogames to be? Frontier's founder Dav id Braben explains that in his company’s latest game The Outsider that they are dealing with these problems that dynamic stories bring up, but also at the same time it leaves an experience for a user who just wants to zone-out and enjoy whatever is presented to them. “Bu t al so, y ou h a ve to c ate r for a l ot o f d i ff e re n t typ e s o f p lay sty l e. Th er e a r e sti ll th e so rt o f p eo p l e wh o w an t a b ra in -o f f exp er i en c e, an d I t h in k th at ' s a go o d th in g - - I d on 't th in k th at ' s a cr it ic i sm . You d on 't wan t to h a v e to th in k, "O h , wh at a m I su p p o se d to d o n ow, " b e cau s e t h at ' s th e fl ip sid e of th i s, th e u n sp o ken p ro b l e m. [O b j ect i v e s] sh ou ld sti ll b e re al ly ob v iou s, b u t t h er e ' s so m eth in g n i c e a b ou t wh en yo u g o th rou gh d o in g wh at y ou 'r e t old , an d y ou th in k, "Wa it a s econ d , th i s i sn ' t q u it e ri gh t !" An d i t' s th at s a me e l e m en t w ith Ou t s id e r wh er e you ' v e got co rru p tio n , th at it' s r eal ly q u it e i n t er e sti n g. N o w, y ou ca n p l ay th rou gh th e [ str ai gh t fo rw ard ] rou t e, an d you en d u p wi th q u it e an in t er e st in g en d in g, b u t you can al so b r ea k of f at an y se co n d , an d st art q u e st ion in g wh y th i n g s are h ap p en in g th e way t h ey 'r e h a p p e n in g.” [ 5 ] Of course in practice the idea of doing dynamic stories seems like a visionary ready to fail because the idea of having entertainment this way in the videogame space appears to be a gigantic piece of work to tackle. Many titles have indeed failed at this, notably Lionhead’s Fable game; altho ugh this could be more put down to things being cut late on in the development and promises not being delivered o n. The games visionary, Peter Molyneux OBE, has stated after the original Fable game came out that they failed to deliver on what they promised originally to gamers and went as far as publicly apo logising to fans of the game for not delivering on pro mises m ade during the titles development. “If I h a v e m en t ion ed an y f eatu r e in th e p a st wh ich , f or wh a te v e r r ea so n , d id n 't m ak e it as I d e sc rib ed in to F ab l e, I ap o lo gi s e. E v e ry f e a tu r e I h a ve e v e r ta lk ed ab ou t WA S i n d e v elo p m en t, b u t n ot al l mad e i t. Of te n th e re a son i s th at th e f ea tu r e d id n ot m ak e s en s e.” [ 6 ] A BBC article shortly after the game was released also referenced Fable’s attempt to change the industry and how story and gameplay options would be delivered to the audience. 9 “It wou ld o f f er a l mo st u n li mi te d fr e ed o m wi th a d izzy in g n u mb er of con s eq u en c e s fo r e v ery a ct ion , w e w er e t old . Th r e e y ea r s l at er a n d th e ga m e i s fi n al ly ou t, b u t it b ea r s on ly a p a s sin g re s e mb lan ce to th e tit l e fir s t sp ok en ab ou t in su ch g lo win g t er m s.” [ 7 ] The BBC article gives a glimpse at the promises Molyneux and his team wished they could have delivered on when making the original Fable gam e with regards to dynamic story and ho w more gameplay choices would be given to the user and with also having more consequence at the same time with the players actions, and undo ubtedly these promises were explored during the development of the title. Lionhead Studio’s is no small fry in the gam e development world either, and its designers are some of the finest out there. So when they have had to scale back ideas and thought pr o cesses that they wished to implement into a game from a design point then we can assume that again the industry is still in its infancy with all these potential possibilities but only gradual development on what we can achieve is being carried out. But it ’s a reassurance that that potential is there for our medium to be something bigger than what it currently is. Fable, and its sequel Fable 2, are the titles that are often referenced in this space by gamers when asked about notable titles that attempted to deliver a gameplay experience that is dynamic in the freedom which is given to the audience. I personally think this was a stepping stone tho ugh, and obviously many titles after this looked back at Fable’s development and tried to work out its shortcomings, as well as the final product to see what worked and what failed. In my eyes Peter Molyneux and the Lionhead team which has created the Fable series of games have done more than a great favour to progressing how dynamic stories can be told in a videog ame. For our games to be looked at as more of a sophisticated art form to the mass -market then we as developers need to push these boundaries of game design, find our limits, and at the same time develop ways in which players feel attached to their actions and consequences. He also believes that this progression with stories and how they attempted to deal with player to character relationships is what ultimately will attract a wider audience to videogames. The BBC interview with him explains his ambitions a s a game creator. “To reach his ambitions Molyneux has spent a long time tackling two key issues: how to make people care about the game and how to make it rich and deep enough to satisfy hardcore gamers and simple enough to attract new players. "I wa n t p eop l e to s it d o wn a n d p l ay th e ga m e w ith a f ri en d . No w so m et i m e s you r fri en d cou l d b e a ga m er . B u t p rob ab ly mor e li ke ly yo u r f ri en d i s goin g t o b e s om eon e wh o h a s n e v er p lay ed t h e ga m e b e for e .“ 10 "B oth of y ou sh o u ld f e el good ab ou t wh at you a r e d o in g, n eit h e r o f y ou sh ou ld f e el stu p id a b ou t wh at yo u a re d oin g. " [ 8 ] Indie games I want to avoid examples of big -budget titles and go back to how to deal with the problem of narrative and gameplay conflicting. Indie gam es like Rod Humble’s Marriage [9] and Gravitation by Jason Rohrer are two examples that leave the narrative, themes and ideas of a game to be portrayed through the use of gameplay, perceptual primitives and also colours and shapes on screen. The Marriage itself is a sm all free downloadabl e game which encompasses two squares, one being pink and the other being blue [figure 2 ]. The game features an attractio n between the two squares along with other primi tives that are shown as circles. The game would be seen as abstract by the majority of p eople and in a way not actually feel like a game, but the idea of how it’s communicating is what we’re after here. The Marriage communicates to the user thro ugh how the game plays and the on -screen primitives. This is then depicted as a marriage, where the blue square represents the husband, while the pink square is obv iously the wife. The circle primitives represent o utside pro blems, chores or maybe even difficulties that the marriage has to deal with. These circle primitives then affect the size of the bl ue and pink squares making one more dominant in the space while also dragging them apart. A healthy balance here is key for gameplay to progress. This breakdown of the game is definitely possible to understand without the need to explain it. Colours being representations and then also themes being extracted with how the game plays. Fig.2 – Rod Humble’s ‘The Marriage’ 11 Big budget titles do this, but it's only possible to see these primitiv es’ once high level visuals and everything else we expect from a ga me nowadays is removed. At its core they still retain these themes which you’d no t need the visuals and everything else to hide. Here it’s a case of small indie games retaining clarity; its fun damentals are not lost unlike a game which has a m ulti millio n pound budget alo ng with a three y ear development time. So if we were to extend The Marriage’s way of expressing itself and how it communicates with the user to any game, then anytime a system behaviour is setup then that system communicates something to th e player (whether the meaning is intentional or not). The Marriage has thematic elements but doesn’t tell a story. I’ll call this way of doing things the ‘progressive system’, while the meaning itself is the ‘progressive meaning’. With how mainstream vid eo games are made I feel designers are not thinking about the pro gressive meaning, of which co mes from the users actions and what they see on screen if the content was boiled down to its primitives. In a way the medium is being used to fill in the blanks a s much as possible from using techniques from both films and literature, and not quite using its unique aspect of ‘play’ and interaction to tell the narrative o r for the user to work it out through patterns and puzzles that the game offers . While designers are m ore focusing on implementing a story as well as gameplay mechanics that are ‘fun’. These stories and ‘fun’ mechanics tend to have separate meanings that would then often clash; this is because the sto ry isn’t designed around the ‘fun’ mechanics. Again though, the games industry now reaches people of all ages while everyone also has different tastes in what they’d like to take in with their spare tim e (which of course is always limited), so maybe this way of ignoring using techniques fro m other media is a non -entity. For me though I desire that this experimentation is taken out more often and we see more of it in a way that a game communicates through the actio ns made by the user and the core primitives that the user sees on-screen and if we have to look at the indie game space for inspiration then so be it. Indie game designers don’t have the money, the large 30 -1 00 team of people or a street date that needs to be met no matter what; they always have the core elements of interactivity and learning patterns as foundatio ns which big budget titles tend to put as a lesser importance during development. 12 Conclusion I've given examples of my feelings as to why I feel the way in which we tell our narratives in gam es could be very much progr essed and there are still ways in which we can tie our gameplay sequences and patterns to carry more meaning and our actions in a game to also have meaningful consequence. Whether this is what solely is holding back videogames from being a sophisticated medium could forever be debated, but my opinio n is that this is our problem. Parts of the audience are still confused or possibly even scared of what unfamiliarity’s the videogames we create posses. I could define music, film as well as literature (as could anyone else), but when given the task of trying to explain what a game is I feel no one could ever accurately deliver a statement. Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman in their book Rules of Play deliv er something which I feel is probably the most systematic explanation being “a system in which players engage in an artificial conflict, defined by rules, that results in a quantifiable outcome” [10] although at the same time I'd still questio n it because aren't gam es really just a load of old fun, and defining how to create fun is then even more of a task in my opinio n. Another notable game designer in Sid Meier illustrates a game is sim ply “a series of meaningful choices.” [11] This example of what represents a ‘game’ to him is in many ways reiterating my stance, F ullerton’s, and also Warren Spector’s that we need to strive for meaningful choices through our actions and how we interact with representations on screen. This in my eyes is what a game is; simply meaningful cho ices that resonate with the audience and the game player. Many will still have the o pinion that v ideogames as a sophisticated medium can only be taken as seriously as something along the lines of your typical Hollywood popcorn flick, where games designers will only ever explore conditio ns like sex a nd violence in our narratives to the point where it will always be deemed as shallow, having little meaning with our actions and the consequences that follow. The game Grand Theft Auto steps upon these themes, and altho ugh parts of the audience see these parts as shallow, as progressing our boundaries as game designers it is al so pushing these limits that have yet to be explored in o ur medium of videogames which both literature and cinema did in both their infancies and have progressed to the point where they are less critiqued . An example being in literature where Mills & Boon novels have in the past attracted incensed critics to both the content and thought process these books suggest to their readers [12], this is a case of these bo undaries being explored in this medium when it was in its infancy, as well as culture changing w ith the times . Will videogames take their rightful place among other forms of entertainment is only something history will dictate when we look back in years to come as something meaningful, a learning experience and actions that as games players we felt fulfilled that it was so mething that changed our lives. 13 References 1. Atkins, Barry. (2003) More Than a Game. Manchester University P ress. 2. Fullerton, Tracy. (March, 2004) “Improving Player Choices” From the World Wide Web:http://www.gam asutra.com/features/20040310/fullerton_01.shtml 3. Fear, Ed. (March 20th, 2008) "Q&A: Warren Spector". From the World Wide Web: http://www.dev elopmag.com/interviews/149/QA -Warren-SpectorPart-2 4. Lindley, Craig A. (2002 ) Conditioning, Learning and Creatio n in Games:Narrative, The Gameplay Gestalt and Ge nerative 5. Braben, David. (January, 2008) “David Braben on dynamic stories in games” From the World Wide Web: http://www.intrinsicalgorithm.com/IAonAI/2 008/01/david -braben -ondynamic -stories -in.html 6. Slashdot | Peter Molyneux Apologizes for Fable http://games.slashdot.org/article.pl?sid =04/ 10/01/1651219 7. BBC NEWS | Technolo gy | Fable falls short of legend http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/technology/3726100.stm 8. BBC NEWS | Technolo gy | Molyneux driven by past failure http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/technology/7262202.stm 14 9. Rod Humble’s “The M arriage” From the World Wide Web: http://www.rodvik.com/rodgames/ 10. Salen, Katie; Zimmerman, Eric. (2003) Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamenta ls. 11. Koster, Raph. (2005) Theory of Fun for Game Design. Paraglyph. 12. Mills & Boon: 100 years of heaven or hell? | Life and style | The Guardian http://www.guardian.co.uk/ lifeandstyle/2007/dec/05/women.fiction 15 Bibliography Internet Sources: Fullerton, Tracy. “Tracy Fullerton, Game Design, Bio”. From the World Wide Web: http://tracyfullerton.com/bio/ CMP Media. (2008) Game Design Track. From the World Wide Web: http://www.gdconf.com/gamedesign/ Simulation. Zero Gam e Studio, The Interactive Institute, Sweden. From the World Wide Web: http://www.tii.se/zerogame/pdfs/NILE.pdf Peter Molyneux at Moby Games http://www.mobygames.com/developer/sheet/view/developerId,1 274/ Video Games: Jason Ro hrer’s “Gravitation” From the World Wide Web: http://hcsoftware.sourceforge.net/jaso n -ro hrer/ Rod Humble’s “The M arriage” From the World Wide Web: http://www.rodvik.com/rodgames/ 2K Games. Bioshock, 2007. Nintendo, Inc. Wii Sports, 2007. Nintendo, Inc. Dr Kawashima’s Brain T raining: How Old Is Your Brain?, 2006. 16 Namco Bandai Games, Inc. Pac -Man, 1980. Frontier Developments Ltd. The Outsider, 2 009. Lionhead Studios, Microsoft Game Stu dios. Fable, 2004. Rockstar Games. Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas, 2004. Books: Atkins, Barry. (2003) More Than a Game. Manchester University P ress. Wolf, Mark J. P; Perron, Bernard. (2003) The Video Game Theory Reader. Routledge. Koster, Raph. (2005 ) Theory of Fun for Game Design. Paraglyph. Salen, Katie; Zimmerman, Eric. (2003) Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. MIT Press. Nelmes, Jill. (2003) An Intro duction to Film Studies. Routledge. 17