English I (Old Standards) Quiz Reading: Understanding and Using

advertisement

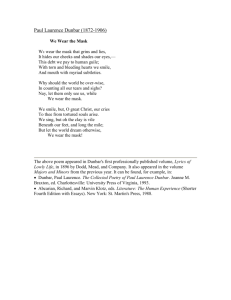

English I (Old Standards) Quiz Reading: Understanding and Using Literary Texts - (E1-1.1) Compare Contrast Ideas, (E1-1.4) Character, Plot, Theme , (E1-1.5) Author's Craft Writing: Developing Written Communications - (E1-4) Written Conventions, (E1-4) Proofreading Skills Reading: Building Vocabulary - (E1-3.1) Vocabulary Context Clues Student Name: _______________________ Teacher Name: Cynthia McQueen Double Research Passage: “Walt Whitman,” “When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer,” and “On the Beach at Night” By: Sasha Peterson & Walt Whitman Walt Whitman By: Sasha Peterson 1Walt Whitman was one of the most influential poets in American history. Whitman believed that poetry should be written for the common people, not just for scholars. This new attitude toward poetry was shaped by his own experience with education, as well as his involvement in nineteenth-century politics. 2Born on May 31, 1819, Whitman was the second son in a family of nine children. The family lived on Long Island, where Whitman’s father worked as a house builder. An apprenticeship with a printer at age twelve cemented Whitman’s life-long love of literature. As for education, he was mostly self-taught. He spent his teen years reading Shakespeare, Dante, and the Bible. His short career as a printer in New York City ended when a fire destroyed the printing district. 3At age seventeen, Whitman began teaching in one-room schoolhouses to make ends meet. Sometimes he had more than eighty students in one classroom, ranging in age from five to fifteen. His teaching techniques were rather progressive for the time. He refused to use corporal punishment, and he often asked students to say their thoughts aloud. Whitman even invented educational games, used his own poems instead of traditional texts, and encouraged children to ask him anything. This teaching philosophy is explored in his famous poem “Song of Myself.” In the poem, the speaker attempts to answer a child’s question, “What is grass?” The narrator describes how the simple things in life, like grass, are often more complex than we think they are. 4By 1841, Whitman had turned to journalism. He even founded his own newspaper. In 1848, he moved to New Orleans to be the editor of the New Orleans Crescent. It was in New Orleans that Whitman witnessed the cruelty of slavery for the first time. For years, he had been writing for newspapers that addressed primarily white issues and ignored the plight of the slaves. His experience in New Orleans had a profound effect on his attitude toward race and politics. Though he was not an abolitionist, Whitman did oppose the extension of slavery into territories gained from the Mexican-American War. 5Whitman moved back to New York that same year and founded another newspaper, the Brooklyn Freeman. During this time, he formed friendships with other writers and radical thinkers of the same mind. Whitman also continued to develop his literary skills, taking his free verse poetry in new directions. It was during this period that he developed the universal “I” used in his famous collection of poetry Leaves of Grass. Whitman was famous for exploring the interconnectedness of all things. Other themes in Whitman’s poetry include the endurance of love and the role of the poet in society. 6When the Civil War began in 1861, Whitman volunteered as a nurse in the hospitals of New York and Washington, D.C. He also served as a clerk for the Department of the Interior during his eleven years in the nation’s capital. In the 1870s, Whitman moved to New Jersey to be closer to his ailing mother. He published many poems before his death on March 26, 1892. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ When I Heard the Learn'd Astronomer By: Walt Whitman 1 When I heard the learn'd astronomer, When the proofs, the figures, were ranged in columns before me, When I was shown the charts and diagrams, to add, divide, and measure them, When I sitting heard the astronomer where he lectured with much applause in the lecture-room, How soon unaccountable I became tired and sick, Till rising and gliding out I wander'd off by myself, In the mystical moist night-air, and from time to time, Look'd up in perfect silence at the stars. -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------On the Beach at Night By: Walt Whitman 1 On the beach at night, Stands a child with her father, Watching the east, the autumn sky. 2 Up through the darkness, While ravening clouds, the burial clouds, in black masses spreading, Lower sullen and fast athwart and down the sky, Amid a transparent clear belt of ether yet left in the east, Ascends large and calm the lord-star Jupiter, And nigh at hand, only a very little above, Swim the delicate sisters the Pleiades. 3 From the beach the child holding the hand of her father, Those burial-clouds that lower victorious soon to devour all, Watching, silently weeps. 4 Weep not, child, Weep not, my darling, With these kisses let me remove your tears, The ravening clouds shall not long be victorious, They shall not long possess the sky, they devour the stars only in apparition, Jupiter shall emerge, be patient, watch again another night, the Pleiades shall emerge, They are immortal, all those stars both silvery and golden shall shine out again, The great stars and the little ones shall shine out again, they endure, The vast immortal suns and the long-enduring pensive moons shall again shine. 5Then dearest child mournest thou only for Jupiter? Considerest thou alone the burial of the stars? 6Something there is, (With my lips soothing thee, adding I whisper, I give thee the first suggestion, the problem and indirection,) Something there is more immortal even than the stars, (Many the burials, many the days and nights, passing away,) Something that shall endure longer even than lustrous Jupiter Longer than sun or any revolving satellite, Or the radiant sisters the Pleiades. 1) Based on both poems, which is the BEST conclusion to draw about Whitman’s opinion of the stars? A) He finds inspiration in the stars. B) He feels disconnected from the stars. C) He thinks the stars are insignificant. D) He believes the stars are guiding him. 2) With which statement would both Walt Whitman and the speaker of “When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer” agree? A) Teachers always have the answers. B) Classrooms should have strict rules. C) There are many different ways to learn. D) Students should only speak when spoken to. 3) With which figure would Walt Whitman MOST LIKELY identify? A) the child in “On the Beach at Night” B) the father in “On the Beach at Night” C) the speaker in “When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer” D) the astronomer in “When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer” 4) Based on both the biography and “On the Beach at Night,” which of these was MOST LIKELY important to Walt Whitman? A) his money B) his family C) his college degrees D) his fans and readers -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------A Girl of the Limberlost By: Gene Stratton-Porter 1 Elnora unlocked the case, took out the pail, put the napkin in it, pulled the ribbon from her hair, binding it down tightly again and followed to the road. From afar she could see her mother in the doorway. She blinked her eyes, and tried to smile as she answered Wesley Sinton, and indeed she did feel better. She knew now what she had to expect, where to go, and what to do. Get the books she must; when she had them, she would show those city girls and boys how to prepare and recite lessons, how to walk with a brave heart; and they could show her how to wear pretty clothes and have good times. 2 As she neared the door her mother reached for the pail. "I forgot to tell you to bring home your scraps for the chickens," she said. 3 Elnora entered. "There weren't any scraps, and I'm hungry again as I ever was in my life." 4 "I thought likely you would be," said Mrs. Comstock, "and so I got supper ready. We can eat first, and do the work afterward. What kept you so? I expected you an hour ago." 5 Elnora looked into her mother's face and smiled. It was a queer sort of a little smile, and would have reached the depths with any normal mother. 6 "I see you've been bawling," said Mrs. Comstock. "I thought you'd get your fill in a hurry. That's why I wouldn't go to any expense. If we keep out of the poorhouse we have to cut the corners close. It's likely this Brushwood road tax will eat up all we've saved in years. Where the land tax is to come from I don't know. It gets bigger every year. If they are going to dredge the swamp ditch again they'll just have to take the land to pay for it. I can't, that's all! We'll get up early in the morning and gather and hull the beans for winter, and put in the rest of the day hoeing the turnips." 7 Elnora again smiled that pitiful smile. 8 "Do you think I didn't know that I was funny and would be laughed at?" she asked. 9 "Funny?" cried Mrs. Comstock hotly. 10 "Yes, funny! A regular caricature," answered Elnora. "No one else wore calico, not even one other. No one else wore high heavy shoes, not even one. No one else had such a funny little old hat; my hair was not right, my ribbon invisible compared with the others, I did not know where to go, or what to do, and I had no books. What a spectacle I made for them!" Elnora laughed nervously at her own picture. "But there are always two sides! The professor said in the algebra class that he never had a better solution and explanation than mine of the proposition he gave me, which scored one for me in spite of my clothes." 11 "Well, I wouldn't brag on myself!" 12 "That was poor taste," admitted Elnora. "But, you see, it is a case of whistling to keep up my courage. I honestly could see that I would have looked just as well as the rest of them if I had been dressed as they were. We can't afford that, so I have to find something else to brace me. It was rather bad, mother!" 13 "Well, I'm glad you got enough of it!" 14 "Oh, but I haven't" hurried in Elnora. "I just got a start. The hardest is over. To-morrow they won't be surprised. They will know what to expect. I am sorry to hear about the dredge. Is it really going through?" 15 "Yes. I got my notification today. The tax will be something enormous. I don't know as I can spare you, even if you are willing to be a laughing-stock for the town." 16 With every bite Elnora's courage returned, for she was a healthy young thing. 17 "You've heard about doing evil that good might come from it," she said. "Well, mother mine, it's something like that with me. I'm willing to bear the hard part to pay for what I'll learn. Already I have selected the ward building in which I shall teach in about four years. I am going to ask for a room with a south exposure so that the flowers and moths I take in from the swamp to show the children will do well." 18 "You little idiot!" said Mrs. Comstock. "How are you going to pay your expenses?" 19 "Now that is just what I was going to ask you!" said Elnora. "You see, I have had two startling pieces of news to-day. I did not know I would need any money. I thought the city furnished the books, and there is an out-of-town tuition, also. I need ten dollars in the morning. Will you please let me have it?" 20 "Ten dollars!" cried Mrs. Comstock. "Ten dollars! Why don't you say a hundred and be done with it! I could get one as easy as the other. I told you! I told you I couldn't raise a cent. Every year expenses grow bigger and bigger. I told you not to ask for money!" 21 "I never meant to," replied Elnora. "I thought clothes were all I needed and I could bear them. I never knew about buying books and tuition." 22 "Well, I did!" said Mrs. Comstock. "I knew what you would run into! But you are so bull-dog stubborn, and so set in your way, I thought I would just let you try the world a little and see how you liked it!" 23 Elnora pushed back her chair and looked at her mother. 24 "Do you mean to say," she demanded, "that you knew, when you let me go into a city classroom and reveal the fact before all of them that I expected to have my books handed out to me; do you mean to say that you knew I had to pay for them?" Mrs. Comstock evaded the direct question. 25 "Anybody but an idiot mooning over a book or wasting time prowling the woods would have known you had to pay. Everybody has to pay for everything. Life is made up of pay, pay, pay! It's always and forever pay! If you don't pay one way you do another! Of course, I knew you had to pay. Of course, I knew you would come home blubbering! But you don't get a penny! I haven't one cent, and can't get one! Have your way if you are determined, but I think you will find the road somewhat rocky." 26 "Swampy, you mean, mother," corrected Elnora. She arose white and trembling. "Perhaps some day God will teach me how to understand you. He knows I do not now. You can't possibly realize just what you let me go through to-day, or how you let me go, but I'll tell you this: You understand enough that if you had the money, and would offer it to me, I wouldn't touch it now. And I'll tell you this much more. I'll get it myself. I'll raise it, and do it some honest way. I am going back tomorrow, the next day, and the next. You need not come out, I'll do the night work, and hoe the turnips." 27 It was ten o'clock when the chickens, pigs, and cattle were fed, the turnips hoed, and a heap of bean vines was stacked beside the back door. 5) The characters' traits are revealed primarily through A) dialogue B) imagery C) narration D) soliloquy 6) Which BEST identifies Elnora's main problem and its resolution? A) Elnora cannot manage school work and farm chores. Wesley Sinton will help. B) Elnora needs money for books and out-of-town tuition. She will raise the money herself. C) Elnora's clothes caused her to be laughed at by the city girls. She will sew new clothes. D) Elnora cannot convince Wesley Sinton to help her with school costs. She will raise the money herself. 7) What is a theme for the passage? A) Sometimes determination is all you have. B) Money is the most important thing in the world. C) Mothers and daughters cannot find a common ground. D) You should not be educated if you do not have money. 8) Why does Elnora refer to herself as ‘a regular caricature?’ A) She has a good sense of humor. B) The other students drew pictures of her. C) Everything about her is orderly and regular. D) She felt like she was an object of ridicule. 9) How does the author convey that Elnora is a strong, determined, and goal-oriented young woman? A) by showing Elnora remain firm in her goals in spite of humiliation B) by showing that Elnora will never back down from a fight--even a fist-fight C) by showing her standing up to the kids at school while they are taunting her D) by describing how all of Elnora's relatives are strong, determined, and goal-oriented 10) How does Elnora compare in appearance to the city kids who attend her school? A) Elnora happily is dressed just as the city kids are and fits right in. B) Elnora is dressed like a homeless child, with no shoes and burlap sack. C) Elnora is dressed far fancier than any of the city kids bothered to dress for school. D) Elnora looks out of place, like a country bumpkin wearing poor clothes that are out of fashion. Dr. Heidegger’s Experiment By: Nathaniel Hawthorne 1 That very singular man, old Dr. Heidegger, once invited four venerable friends to meet him in his study. There were three white-bearded gentlemen, Mr. Medbourne, Colonel Killigrew, and Mr. Gascoigne, and a withered gentlewoman, whose name was the Widow Wycherly. They were all melancholy old creatures, who had been unfortunate in life, and whose greatest misfortune it was that they were not long ago in their graves. It is a circumstance worth mentioning that each of these three old gentlemen, Mr. Medbourne, Colonel Killigrew, and Mr. Gascoigne, were early lovers of the Widow Wycherly, and had once been on the point of cutting each other's throats for her sake. And, before proceeding further, I will merely hint that Dr. Heidegger and all his foul guests were sometimes thought to be a little beside themselves,--as is not unfrequently the case with old people, when worried either by present troubles or woeful recollections. 2 ‘My dear old friends,’ said Dr. Heidegger, motioning them to be seated, ‘I am desirous of your assistance in one of those little experiments with which I amuse myself here in my study.’ 3 If all stories were true, Dr. Heidegger's study must have been a very curious place. It was a dim, old-fashioned chamber, festooned with cobwebs, and besprinkled with antique dust. Around the walls stood several oaken bookcases, the lower shelves of which were filled with rows of gigantic folios and black-letter quartos, and the upper with little parchmentcovered duodecimos. Over the central bookcase was a bronze bust of Hippocrates, with which, according to some authorities, Dr. Heidegger was accustomed to hold consultations in all difficult cases of his practice. In the obscurest corner of the room stood a tall and narrow oaken closet, with its door ajar, within which doubtfully appeared a skeleton. Between two of the bookcases hung a looking-glass, presenting its high and dusty plate within a tarnished gilt frame. Among many wonderful stories related of this mirror, it was fabled that the spirits of all the doctor's deceased patients dwelt within its verge, and would stare him in the face whenever he looked thitherward. The opposite side of the chamber was ornamented with the full-length portrait of a young lady, arrayed in the faded magnificence of silk, satin, and brocade, and with a visage as faded as her dress. Above half a century ago, Dr. Heidegger had been on the point of marriage with this young lady; but, being affected with some slight disorder, she had swallowed one of her lover's prescriptions, and died on the bridal evening. The greatest curiosity of the study remains to be mentioned; it was a ponderous folio volume, bound in black leather, with massive silver clasps. There were no letters on the back, and nobody could tell the title of the book. But it was well known to be a book of magic; and once, when a chambermaid had lifted it, merely to brush away the dust, the skeleton had rattled in its closet, the picture of the young lady had stepped one foot upon the floor, and several ghastly faces had peeped forth from the mirror; while the brazen head of Hippocrates frowned, and said,--"Forbear!" 4 On the summer afternoon of our tale a small round table, as black as ebony, stood in the centre of the room, sustaining a cut-glass vase of beautiful form and elaborate workmanship. The sunshine came through the window, between the heavy festoons of two faded damask curtains, and fell directly across this vase; so that a mild splendor was reflected from it on the ashen visages of the five old people who sat around. Four champagne glasses were also on the table. 5 ‘My dear old friends,’ repeated Dr. Heidegger, ‘may I reckon on your aid in performing an exceedingly curious experiment?’ 6 When the doctor's four guests heard him talk of his proposed experiment, they anticipated nothing more wonderful than the murder of a mouse in an air pump, or the examination of a cobweb by the microscope, or some similar nonsense, with which he was constantly in the habit of pestering his intimates. But without waiting for a reply, Dr. Heidegger hobbled across the chamber, and returned with the same ponderous folio, bound in black leather, which common report affirmed to be a book of magic. Undoing the silver clasps, he opened the volume, and took from among its black-letter pages a rose, or what was once a rose, though now the green leaves and crimson petals had assumed one brownish hue, and the ancient flower seemed ready to crumble to dust in the doctor's hands. 7 ‘This rose," said Dr. Heidegger, with a sigh, ‘this same withered and crumbling flower, blossomed five and fifty years ago. It was given me by Sylvia Ward, whose portrait hangs yonder; and I meant to wear it in my bosom at our wedding. Five and fifty years it has been treasured between the leaves of this old volume. Now, would you deem it possible that this rose of half a century could ever bloom again?’ 8 ‘Nonsense!’ said the Widow Wycherly, with a peevish toss of her head. ‘You might as well ask whether an old woman’s wrinkled face could ever bloom again.’ 9 ‘See!’ answered Dr. Heidegger. 10 He uncovered the vase, and threw the faded rose into the water which it contained. At first, it lay lightly on the surface of the fluid, appearing to imbibe none of its moisture. Soon, however, a singular change began to be visible. The crushed and dried petals stirred, and assumed a deepening tinge of crimson, as if the flower were reviving from a deathlike slumber; the slender stalk and twigs of foliage became green; and there was the rose of half a century, looking as fresh as when Sylvia Ward had first given it to her lover. It was scarcely full blown; for some of its delicate red leaves curled modestly around its moist bosom, within which two or three dewdrops were sparkling. 11 ‘That is certainly a very pretty deception,’ said the doctor's friends; carelessly, however, for they had witnessed greater miracles at a conjurer's show; ‘pray how was it effected?’ 12 ‘Did you never hear of the ’Fountain of Youth?’ ‘ asked Dr. Heidegger, ‘which Ponce De Leon, the Spanish adventurer, went in search of two or three centuries ago?’ 13 ‘But did Ponce De Leon ever find it?’ said the Widow Wycherly. 14 ‘No,’ answered Dr. Heidegger, ‘for he never sought it in the right place. The famous Fountain of Youth, if I am rightly informed, is situated in the southern part of the Floridian peninsula, not far from Lake Macaco. Its source is overshadowed by several gigantic magnolias, which, though numberless centuries old, have been kept as fresh as violets by the virtues of this wonderful water. An acquaintance of mine, knowing my curiosity in such matters, has sent me what you see in the vase.’ 15 ‘Ahem!’ said Colonel Killigrew, who believed not a word of the doctor’s story; ‘and what may be the effect of this fluid on the human frame?’ -----------------------------------11) In paragraph 6, why does the author use the word hobbled to describe Dr. Heidegger as he went to get the book of magic? A) to create an image of Dr. Heidegger's movements B) to illustrate the eeriness of the book of magic C) to show that the Dr. Heidegger's study was very crowded D) to avoid using the same words that were used previously 12) How does the tone in the story shift from the beginning to the end? A) It goes from admiring to resentful. B) It goes from doubtful to inquisitive. C) It shifts from excited to lackluster. D) It changes from indifference to anger. 13) The controlling images in this passage deal with which idea(s)? A) old and new B) death and life C) death and magic D) magic and fantasy English Report: A Powerful Poet By: Camille Roberts 1Roberts 1 2Camille Roberts 3Mr. Anthony 41st hour English IV: "A Powerful Poet" 517 November 20— 6"A Powerful Poet" 7Paul Laurence Dunbar was a famous American poet and novelist. 8Dunbar was one of the first African American writers to gain national attention, and his works were greatly influenced by his African American heritage. 9Dunbar was born in 1872 in Dayton, Ohio. 10His parents were freed slaves and his father fought during the Civil War. 11Dunbar's mother shared with him her love of poetry. When Dunbar was a boy, his mother read lines of poetry to him (Slurry 97). 12Soon, began to recite the lines and write short poems. 13During his formative years, Dunbar attended a school in Ohio that was populated mostly by white students. 14Because Dunbar excelled at writing in school, and because he helped edit his school newspaper. 15He and his classmate Orville Wright—who would later go on to invent the airplane with his brother Wilbur—published a daily newspaper together for a very brief time (110 Slurry). 16After high school, Dunbar did not have the opportunity to attend college, he worked as an elevator attendant. 17Because Dunbar's job was monotonous, thinking of concepts for his poetry. 18In 1893 Dunbar published a poetry collection titled Oak and Ivy (Zane 219). 19To spread his work, Dunbar distributed a number of copies of his collection. 20Soon, people began to take notice of Dunbar's eloquent work. 21Although Dunbar's first collection was mildly successful, he experienced financial difficulties and had to go back to work as an elevator attendant (Wong). 22Dunbar did not despair and he continued to write doggedly. 23In 1895 he printed a second collection of poetry titled Majors and Minors. 24When Dunbar published his book and when it became a successful piece of literature. 25Dunbar incorporated a number of different types of poems in this collection. 26Including some that featured a distinct African American dialect. 27Dunbar included this dialect to honor his heritage and he included it to explore African Americans' lives. 28In the years to come, Dunbar would become famous for poems that used this dialect (American Writers Almanac). 29In America during the late 1800s and early 1900s, many intolerant people. 30Dunbar tried to show the plight of African Americans; however, he also tried to celebrate African Americans' rich heritage. 31In 1896, Dunbar received a favorable review in the magazine Harper's Weekly (Wong). 32Almost instantly becoming one of the most famous writers in the country. 33Dunbar continued to write he traveled to Europe, too. 34Dunbar married Alice Moore in 1898; however, soon separated in 1901. 35When he was only thirty years old, contracted an illness called tuberculosis. 36Dunbar fought the illness for almost three years. 37During this time, he also wrote another book called Heart of Happy Hollow. 38This book was not as successful as his other works. 39Dunbar died of tuberculosis in 1906 he was only thirty-three years old (Zane 260). 40By the end of his life, Dunbar had authored twenty-two books. 41Although Dunbar was most famous for his poetry, he also wrote novels, song lyrics, and essays. 42Today, because Dunbar's poems are still being read and enjoyed. 43Paul Laurence Dunbar leaves behind an important legacy many young authors look to Dunbar and his work for inspiration. 44"Books that I Used" 45Johnson, Eliza. "Dunbar, Paul Laurence." American Writers Almanac. 1999 ed. 46Slurry, Markus. "Early Life." San Francisco, CA: Quality Books, 2001. The Life of Paul Laurence Dunbar. 87-126. 47Encyclopedia of American Writers. 2002 ed. Wong, Samantha. "Dunbar, Paul Laurence." 48Zane, Francis. Famous African American Writers. Philadelphia, PA: Reinhart and Weston, 2005. 209-63. -------------------------------------------------- 14) Which of these is the BEST way to change the sentence 43? A) Paul Laurence Dunbar leaves behind an important legacy, many young authors look to Dunbar and his work for inspiration. B) Paul Laurence Dunbar leaves behind an important legacy and many young authors look to Dunbar and his work for inspirati C) Paul Laurence Dunbar leaves behind an important legacy but many young authors look to Dunbar and his work for inspiratio D) Paul Laurence Dunbar leaves behind an important legacy, and many young authors look to Dunbar and his work for inspirat 15) Which of these is the BEST way to rewrite the sentence in line 27? A) Dunbar included this dialect to honor his heritage he included it to explore African Americans' lives. B) Dunbar included this dialect to honor his heritage, he included it to explore African Americans' lives. C) Dunbar included this dialect to honor his heritage and he also included it to explore African Americans' lives. D) Dunbar included this dialect to honor his heritage; furthermore, he included it to explore African Americans' lives. -------------------------------------------------------Jane Eyre By: Charlotte Bronte 1 I resisted all the way: a new thing for me, and a circumstance which greatly strengthened the bad opinion Bessie and Miss Abbot were disposed to entertain of me. The fact is, I was a trifle beside myself; or rather OUT of myself, as the French would say: I was conscious that a moment's mutiny had already rendered me liable to strange penalties, and, like any other rebel slave, I felt resolved, in my desperation, to go all lengths. 2 "Hold her arms, Miss Abbot: she's like a mad cat." 3 "For shame! for shame!" cried the lady's-maid. "What shocking conduct, Miss Eyre, to strike a young gentleman, your benefactress's son! Your young master." 4 "Master! How is he my master? Am I a servant?" 5 "No; you are less than a servant, for you do nothing for your keep. There, sit down, and think over your wickedness." 6 They had got me by this time into the apartment indicated by Mrs. Reed, and had thrust me upon a stool: my impulse was to rise from it like a spring; their two pair of hands arrested me instantly. 7 "If you don't sit still, you must be tied down," said Bessie. "Miss Abbot, lend me your garters; she would break mine directly." 8 Miss Abbot turned to divest a stout leg of the necessary ligature. This preparation for bonds, and the additional ignominy it inferred, took a little of the excitement out of me. 9 "Don't take them off," I cried; "I will not stir." 10 11 In guarantee whereof, I attached myself to my seat by my hands. "Mind you don't," said Bessie; and when she had ascertained that I was really subsiding, she loosened her hold of me; then she and Miss Abbot stood with folded arms, looking darkly and doubtfully on my face, as incredulous of my sanity. 12 "She never did so before," at last said Bessie, turning to the Abigail. 13 "But it was always in her," was the reply. "I've told Missis often my opinion about the child, and Missis agreed with me. She's an underhand little thing: I never saw a girl of her age with so much cover." 14 Bessie answered not; but ere long, addressing me, she said -- "You ought to be aware, Miss, that you are under obligations to Mrs. Reed: she keeps you: if she were to turn you off, you would have to go to the poorhouse." 15 I had nothing to say to these words: they were not new to me: my very first recollections of existence included hints of the same kind. This reproach of my dependence had become a vague sing-song in my ear: very painful and crushing, but only half intelligible. Miss Abbot joined in 16 "And you ought not to think yourself on an equality with the Misses Reed and Master Reed, because Missis kindly allows you to be brought up with them. They will have a great deal of money, and you will have none: it is your place to be humble, and to try to make yourself agreeable to them." 17 "What we tell you is for your good," added Bessie, in no harsh voice, "you should try to be useful and pleasant, then, perhaps, you would have a home here; but if you become passionate and rude, Missis will send you away, I am sure." 18 "Besides," said Miss Abbot, "God will punish her: He might strike her dead in the midst of her tantrums, and then where would she go? Come, Bessie, we will leave her: I wouldn't have her heart for anything. Say your prayers, Miss Eyre, when you are by yourself; for if you don't repent, something bad might be permitted to come down the chimney and fetch you away." "I was conscious that a moment's mutiny had already rendered me liable to strange penalties, and, like any other rebel slave, I felt r my desperation, to go all lengths." 16) What is meant by the term resolved as it is used in this sentence? A) determined B) questioning C) uneasy D) unsure 6 They had got me by this time into the apartment indicated by Mrs. Reed, and had thrust me upon a stool: my impulse was to rise fr spring; their two pair of hands arrested me instantly. 17)What is the meaning of the word arrested as used in this sentence? A) to have a heart attack B) to seize for a short time C) to detain in legal custody D) to stop all motion and growth ‘I was conscious that a moment's mutiny had already rendered me liable to strange penalties, and, like any other rebel slave, I felt re my desperation, to go all lengths.’ 18) What is meant by the term mutiny as it is used in this sentence? A) calmness B) defiance C) outburst D) serenity I had nothing to say to these words: they were not new to me: my very first recollections of existence included hints of the same kin reproach of my dependence had become a vague sing-song in my ear: very painful and crushing, but only half intelligible. 19) Which definition BEST fits the meaning of the word reproach as used in these sentences from paragraph 15 of the passage? A) B) C) D) fear or doubt praise and celebration critical remark or condemnation curiousity or desire for knowledge