Jason Friesen MD

advertisement

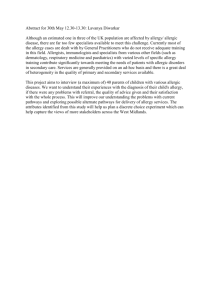

Update on Food Allergy and Asthma JASON FRIESEN MD OREGON ALLERGY ASSOCIATES OAK STREET MEDICAL Prevalence of Food Allergies in the United States Food Young Children Adults Milk 2.5% 0.3% Egg 1.3% 0.2% Peanut 0.8% (~2%) 0.6% Tree Nuts 0.2% 0.5% Fish 0.1% 0.4% Shellfish 0.1% 2.0% Overall 6% (~8%) 3.7% Sampson HA, Update on food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;113:805-19 Perceived prevalence of Food Allergy A whole population birth cohort was established on the Isle of Wight. Parents reported food hypersensitivity in 25.8% of their children. The actual incidence of food hypersensitivity confirmed by open food challenge or DBPCFC at one year was 4.0%. Venter C, Pereira B, Grundy J, Clayton CB, Roberts G, Higgins B, et al. Incidence of parentally reported and clinically diagnosed food hypersensitivity in the first year of life. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006;117:1118-24. Presenting Symptoms by Percent of Occurrence in Pediatric Anaphylactic Patients 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% Cutaneous (n=57) Resp (n=38) Cardio (n=28) Laryngeal (n=25) GI (n=22) Allergy vs. Intolerance IgE Mediated (allergy) Non-IgE Mediated (intolerance) Classic symptom Cutaneous (hives, flushing, swelling) GI (bloating, gas, nausea, diarrhea) Speed Minutes to hours (unlikely >4 hrs) Hours to most of a day Frequency Every time the food is ingested Sporadic Dose Dependency Appears non-dose dependent Appears very dose dependent Casual contact with peanut Thirty highly allergic children underwent the challenges. None experienced a systemic or respiratory reaction. Erythema (3 subjects), pruritus without erythema (5 subjects), and wheal-and-flare reactions (2 subjects) developed only at the site of skin contact with peanut butter. “From this number of participants, it can stated with 96% confidence that at least 90% of highly sensitive children with peanut allergy would not experience a systemic-respiratory reaction from casual exposure to peanut butter.” J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003 Jul;112(1):180-2. Airborne peanut exposure Participants consumed peanuts in various forms to simulate situations that might create airborne peanut allergen. To simulate a school cafeteria setting, participants consumed peanut butter sandwiches. For environments similar to sporting events, participants shelled and consumed roasted peanuts. Participants were encouraged to discard peanut shells on the floor and were also allowed to walk on the shells during many of the sessions. To simulate the environment on commercial airliners, each participant opened 15 bags of unshelled peanuts in small, ½-oz packages and consumed the nuts. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;113:973-6. Airborne peanut exposure J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;113:973-6. Severe and fatal reactions Fear vs. dread “Social scientists have known for a long time that there are dangers whose risks we underestimate, and there are dangers whose risks we overestimate. They talk about the difference between things that we fear and things that we dread. “We fear cancer and heart disease and traffic crashes, but psychopaths and serial killers and airplane crashes are things that we dread. So when a danger seems like it's inexplicable, when we have absolutely no control over it, when suddenly, out of the blue, it causes mass casualties, this causes not fear, but dread. And when it comes to dread, that's when we tend to overestimate the risks.” Incidence of fatal food reactions In food-allergic people, fatal food anaphylaxis has an incidence rate of 1.81 per million personyears (95%CI 0.94, 3.45; range 0.63, 6.68). In sensitivity analysis with different estimated food allergy prevalence, the incidence varied from 1.35 to 2.71 per million person-years. At age 0–19, the incidence rate is 3.25 (1.73, 6.10; range 0.94, 15.75; sensitivity analysis 1.18–6.13). Putting it in perspective Shark attack: 0.1 per million person years Death by lightning: 0.22 per million person years Fatal anaphylaxis: 1-3 per million person years (in allergic persons) Fatal influenza: 100 per million person years (in the US) Using envelope math we can expect a food allergy death in a child every 7-20 years. Risk for Fatal Food Reaction Large majority of victims were adolescents or young adults A prior history of allergy to the specific food is very common. Asthma appears to be a strong risk factor. Epinephrine needs to be given in a timely manner. From Sampson’s original 13 cases: “The six patients who died had symptoms within 3 to 30 minutes of the ingestion of the allergen, but only two received epinephrine in the first hour. All the patients who survived had symptoms within 5 minutes of allergen ingestion, and all but one received epinephrine within 30 minutes.” Peanut and tree nut caused 95% of fatalities. Fatal and near-fatal anaphylactic reactions to food in children and adolescents. Sampson HA - N Engl J Med - 6-AUG-1992; 327(6): 380-4 Epinephrine Epinephrine is safe in children. It may cause pharmacologic adverse effects such as anxiety, fear, restlessness, headache, dizziness, palpitations, pallor, and tremor. Rarely, and especially after overdose, it may lead to ventricular arrhythmias, angina, myocardial infarction, pulmonary edema, sudden sharp increase in blood pressure, and intracranial hemorrhage. There is, however, no absolute contraindication to epinephrine use in anaphylaxis. F. Estelle R. Simons, J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;113:837-44.) Epinephrine EpiPen Jr 0.15mg is optimally dosed for a 15kg child (50%ile 3 years old). EpiPen 0.30mg is optimally dosed for a 30kg child (50%ile 12 years old). Personally I switch up at 20 kg (45 pounds) (50%ile 6 years old). The 5/8” length may be too short to ensure intramuscular injection of epinephrine in obese individuals. Practical tips about food allergy action plans Low threshold for giving epinephrine: Pros: Early administration for life threatening cases. Low risk of significant side effects in children Simpler decision making for non-medical personnel Decreased liability? Cons: Potential cost with ER/ambulance Psychological burden of increased fear High threshold for giving epinephrine: Pros: Decreased inappropriate uses of epinephrine Less “knee jerk” Cost savings of used epi-pen Cons: Increased risk of delayed epi in life threatening case More decision making required Increased liability? The LEAP study SHOULD IT HAVE BEEN CALLED THE “TURN THE WORLD UPSIDE DOWN STUDY”? LEAP study Current guidelines recommended avoiding allergenic foods such as peanut or shellfish until age three for siblings of allergic patients. Is this the right advice? In the UK women were adviced to avoid eating peanuts while pregnant and avoid giving peanuts to children until three yet the incidence of peanut allergy continued to climb. Jewish mothers in the UK were more likely to have peanut allergic kids than Jewish mothers in Israel. One difference was kids in Israel have early exposure to peanut. LEAP study LEAP Study 640 infants between 4 and 11 months randomized to eat at least 6g peanut protein per week. All had eczema, egg allergy or both. Stratified between negative skin prick and positive skin prick. LEAP Study 530 infants had negative skin prick result. 13.7% of avoidance group developed peanut allergy. 1.9% of consumption group developed peanut allergy. (86% risk reduction) 98 infants had positive skin prick results. 35.3% in avoidance group 10.6% in consumption group (70% risk reduction) Siblings of peanut allergic children Prick test early If negative, introduce peanut Practical issues with keeping peanut in house to feed sibling while keeping it away from allergic child. If positive, consider challenge in office or avoidance. Oral immunotherapy • The primary outcome, desensitisation, was recorded for 62% in the active group and none of the control group after six months. 84% of the active group tolerated daily ingestion of 800 mg protein (equivalent to roughly five peanuts). Happening in Oregon Tolerance vs. Desensitization? “bite proof” Cost and coverage Asthma The September epidemic of asthma hospitalizations: School children as disease vectors Neil W Johnston, MSc, Sebastian L. Johnston, MD, PhD, Geoff R. Norman, PhD, Jennifer Dai, MSc, and Malcolm R. Sears, MB, ChB Hospital admissions for asthma in 5 to 15 year olds Neil W. Johnston, J ALLERGY CLIN IMMUNOL; 117 (3); 557 Other Studies find the same thing This effect has been noted across the northern hemisphere: Finland, Canada, United Kingdoms, United States, Mexico, Israel, Trinidad. A parallel post-summer vacation effect has been noted in the southern hemisphere as well: South Africa, Australia, New Zealand Noncompliance? Summer tends to have the fewest asthma admissions. Schedules for school kids are much more chaotic making routines harder to keep. Noncompliance Neil W. Johnston, J ALLERGY CLIN IMMUNOL; 115 (1); 137 Hospitalizations by age in relation to Labor Day Neil W. Johnston, J ALLERGY CLIN IMMUNOL; 117 (3); 557 Short-Course Montelukast for Intermittent Asthma in Children A Randomized Controlled Trial Colin F. Robertson, David Price, Richard Henry, Craig Mellis, Nicholas Glasgow, Dominic Fitzgerald, Amanda J. Lee, Jane Turner, and Melissa Sant Methods Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial comparing 7-20 days of montelukast at the first sign of a URI. 220 children age 2-14 randomized. Results Colin F Robertson, AMER JOUR RESP CRIT CARE, 175; 323 Results, cont. Colin F Robertson, AMER JOUR RESP CRIT CARE, 175; 323 Conclusion “For 100 patient episodes treated with montelukast, there would be an avoidance of one hospital admission, six emergency room attendances, two specialist consultations, and eight GP visits.” Quadrupling the Dose of Inhaled Corticosteroid to Prevent Asthma Exacerbations: A Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled, Parallel-group Clinical Trial Janet Oborne, Kevin Mortimer, Richard B. Hubbard, Anne E Tattersfield, and Tim W Harrison. University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom J Obonre, Am J Respir Crit Care Med Vol 180. pp 598–602, 2009 Results cont. “Among the 94 participants who started the study inhaler, quadrupling the dose of inhaled corticosteroid led to a marked reduction in the need for oral corticosteroids (21 vs. 50%, relative risk reduction, 57%).” Practical consideration: Running through a month’s worth of ICS in one week. Cost and insurance headache. Conclusions September asthma A real event Occurs roughly three weeks after Labor Day. Likely virally driven, although summer noncompliance may play a factor. Having kids on their controller before Labor Day may be beneficial to avoiding an exacerbation. Asthma Phenotypes Not all kids respond the same Stanley J Szefler, JOUR ALLER CLIN IMMUN, 115 (2); 233 Conclusions Phenotypes of asthma An exciting horizon of research Different phenotypes may respond to different modalities of medical therapy. FeNO can help reveal kids who will most likely respond to inhaled steroids. Step-up Therapy Exercise asthma Differential Diagnosis Exercise Asthma VCD Conditioning Symptoms SOB, cough, SOB, cough, wheeze (exp) “wheeze” (insp) SOB Timing Prolonged, worsening after stopping Short, improves when stopped Short, improves when stopped Location Chest Throat / upper chest Diffuse Treatment Albuterol Breathing exercises Exercise Using your inhaler Using an inhaler (with spacer) Shake well for 5-10 seconds. Insert the MDI into the open end of the chamber. Breathe out all the way. Keep your chin up. Place the mouthpiece of the chamber between your teeth and seal your lips tightly around it. Press the canister once. Breathe in slowly through your mouth to completely fill your lungs. If you hear a "horn-like" sound, you are breathing too quickly and need to slow down. Hold your breath for 10 seconds (count to 10 slowly) to allow the medication to reach the airways of the lung. Wait about 1 minute in between puffs. No spacer 1.Shake well for 5-10 seconds. 2.Breathe out all the way. 3.Keep your chin up. 4.Place the mouthpiece of the inhaler between your teeth and seal your lips tightly around it. 5.As you start to breathe in slowly, press down on the canister one time. 6.Keep breathing in slowly to completely fill your lungs. (It should take about 5 to 7 seconds for you to completely breathe in.) 7.Hold your breath for 10 seconds (count to 10 slowly) to allow the medication to reach the airways of the lung. 8.Wait about 1 minute between puffs. 9.Replace the cap on the MDI when finished. New Therapies Biologics Xolair Mepolizumab Generic Advair Jason Friesen MD Email: jason@oregonallergy.net Phone: 541-683-1577 (main) 541-431-9422 (direct)