Goal bank/General Info

advertisement

1 GOALS/DOCUMENTATION COMPONENTS OF GOAL (MAY WANT TO INCLUDE) Complexity Abstract ADL Basic Basic social Complex Personal Simple Cue types No cues Written cues Tactile cues Gestural cues Verbal cues Modeling cues Visual cues Dysphasia techniques 90-90-90 degree positioning Adaptive feeding equipment Altered bolus placement Altered rate Alternating solids and liquids Chin tuck Double swallow Effortful swallow Tilt head Head turn Mendelssohn maneuver Oral search for residuals Super-supraglottic swallow Supraglottic swallow 2 Therapist action verbs (to be used with) ST components Therapist action verbs Components Instructed Introduced Facilitated Emphasized Presented with Modified Upgraded Revised Downgraded Adjusted Initiated Progressed to Educated on Transitioned to Altered Enhanced Coordination Demonstrated Addressed Stimulated Use of Categorization Inferencing Segmented Bolus control Lip seal A/P transit time Laryngeal elevation Swallow initiation Pharyngeal excursion Oral sensation Lingual /labial symmetry Lingual/labial strength Lingual/labial coordination Airway closure Base of tongue retraction y/n accuracy Following commands Obj ID Word retreival 3 Volume Attention Problem solving Memory Tactile manipulation Cause/effect relationship 4 DYSPHAGIA Stages of the swallow: 1. Oral phase Voluntary stage Masticate bolus prevents leaking of food Buccal muscles are tense to prevent pocketing Bolus in front of mouth Labial seal Oral transport substage Voluntary Jaw and lips closed Food moved to back of mouth by tongue Lasts 1 sec 2. Pharyngeal stage- starts when bolus hit faucial arches Involuntary Sensory info from receptors in back of mouth and in pharynx goes to swallowing center in medulla. Palatopharyngeal folds pull together medially to form a slit in upper pharynx which bolus passes through Velum is raised preventing entry of food into the nasopharynx Tongue is retracted preventing food from re-entering mouth Laryngeal substage--airway protection Larynx and hyoid bone pulled upward and forward, enlarging the pharynx and creating a vacuum in hypo pharynx which pulls the bolus downward. True and false vocal folds adduct (closure begins at level of true VF and progresses to false VF and then to ari-epiglottis folds. Epiglottis drops over top of larynx protecting airway and diverting bolus to pyriform sinuses. The bolus passes down on both sides of epiglottis. If liquid bolus, epiglottis acts as ledge to slow movement thru pharynx giving the VF time to adduct and larynx time to elevate. 3. Esophageal stage Involuntary Bolus moved down esophagus via peristalsis and gravity Larynx lowers to normal position Cricopharyngeus muscle contracts to prevent reflux Lasts 8-20s (in elderly peristalsis is slower) (Logemann, 1983, 1989,1997; Cherney, 1994) SWALLOW CHANGES IN HEALTHY AGING ADULTS A. Primary Effects of Normal Aging - Effects of Age Alone in HEALTHY Elderly 5 1. The 60 – 80-year-old a. Timing of the Swallow 1) Oral transit times slightly but significantly longer in older adults (.5-.6 sec). Tipper (tongue tip against alveolar ridge at initiation of swallow) vs. dipper (tongue tip behind lower teeth at initiation of swallow) swallow types - Elderly more often dippers 2) Pharyngeal delay times slightly but significantly longer in older adults (.5-.6 sec) 3) Pharyngeal wall contraction inconsistently found to be slower 4) Reduced tongue pressure b. Safety and Efficiency of the Swallow 1) Penetration occurs more frequently 2) Aspiration occurs no more frequently in the elderly 3) Residue is generally only slightly greater (2-3%) in the elderly than in younger adults 2. 80+ year-olds - Range and pattern of pharyngeal movements during the swallow in 80-year-olds are different from younger adults which increase the older adult's risk of dysphagia as the result of illness and subsequent general weakness. a. Reduced reserve - especially in men 1) Hyoid & laryngeal maximum vertical movement significantly reduced in the elderly 2) Hyoid and laryngeal movements up to the time of cricopharyngeal opening virtually identical in young adults and elderly patients b. Reduced flexibility 1) Cricopharyngeal opening durations across volumes reduced in the elderly 2) Cricopharyngeal opening diameter across volumes reduced in the elderly a) Timing similar to 60-80-year-olds b) Safety and efficiency of swallow unchanged c. Range of motion exercises may improve reserve and flexibility in otherwise normal, healthy elderly. 3. Conclusions a. Healthy older adults exhibit highly safe and efficient swallow b Illness causing extreme weakness may cause dysphagia in otherwise normal over 80-year-olds © 2008 Jeri A. Logemann, Ph.D http://americandysphagianetwork.org/Changes_in_Normal_Swallow_with_Age.pdf The components of normal s wallowing process. A problem with swallowing can be caused by a defect in any of them. 6 Signs and Symptoms: Oro-pharyngeal dysphagia include the following: Difficulty trying to swallow Choking or breathing saliva into your lungs while swallowing Coughing while swallowing Regurgitating liquid through your nose Breathing in food while swallowing Weak voice Weight loss Esophageal dysphagia include the following: Pressure sensation in your mid-chest area Sensation of food stuck in your throat or chest Chest pain Pain with swallowing Chronic heartburn Belching Sore throat 2011 University of Maryland Medical Center Signs and symptoms of aspiration Eyes watering Reddening of face Change in rate of respiration Difficulty/inability to breathe Change in lung sounds Audible breathing Facial grimacing 7 Coughing Gagging Attempts to clear throat Wet vocal quality Chest pain High/low back pain Cannot produce voice, or can only talk in whisper States that something is stick in throat Feeling of fullness in throat Dysphagia Assessment and Screening --Long Term Care Screening Clinical sensory motor examination Chart and medication review Meal time and feeding observation Risk for aspiration Oral hygiene Assessment Voice quality Medication review Cognitive screening Swallowing questionnaire Caregiver interview Assess feeding environment Weight and health status Dietary consult and modifications Evaluate need for instrumental assessment (The Swallowing Manual: Rubin, Broniatowsky, Kelly; 2000) DYSPHAGIA ASSESSMENT QUESTIONNAIRE Do you have difficulty swallowing? Do you have pain when you swallow? Do you have difficulty chewing hard foods? 8 Do you have a dry mouth? Do you have excess saliva or drooling? Do you cough or choke before, during, or after swallowing? Does your voice become hoarse after swallowing? Do you notice food coming up into your nose? Do you have heartburn or indigestion? Do you have difficulty swallowing liquids/solids/pills? Do you react to spicy foods? Has your reaction to hot or cold food changed? Have you had episodes of airway obstruction? Have you had pneumonia or aspiration pneumonia? (The Swallowing Manual: Rubin, Broniatowsky, Kelly; 2000) When a diet may need modified: If there is a(n): Oral dysfunction--thin liquids Delayed swallow--thicker liquids Reduced laryngeal closure--purees and thickened liquids (Hegde, Davis 2010) SWALLOWING GOALS Short Term GOAL Pt will…. Consume (diet level) without any difficulty-- TARGET HOW TO masticating Diet downgrade Dentures in? Moisten food Forming or manipulating bolus Diet downgrade Alternating solids and liquids Liquid wash Increase labial coordination for mastication and swallow from (%) to (%). 9 Increase safe swallow by improving swallow initiation reflex from (seconds) to (seconds) Initiating swallow Thicker bolus Improve oral and pharyngeal control of bolus to increase PO intake. Oral/pharyngeal control Posterior tongue presentation of bolus Apply pressure on tongue with spoon Straw for liquids Utilize compensatory strategy of alternating solids and liquids to assist in bolus manipulation and oral clearance with min/mod/max verbal cues. liquid wash to assist in bolus manipulation and oral clearance 10 Postures that promote safer swallowing Increased sensory awareness (target is to apply sensory stimulus prior to swallow) Modification of volume in food presentation Chin down--widens valleculae Chin up- helps drain food to back of mouth Head rotation toward weaker side-helps direct food to more efficient side of pharynx Chin down and head rotation--may promote better laryngeal closure during swallow Head tilt to stronger side--directs food to that side (Hegde, Davis 2010) Application of downward pressure on tongue with a spoon Sour bolus before presenting normal bolus Cold bolus Bolus that needs to be chewed Large volume bolus (Hegde, Davis 2010) Larger/smaller bolus Slower rate of smaller bolus (Hegde, Davis 2010) Pt will use <dysphasia techniques with <0-100% > accuracy during for <meals/feeds> using <diet/liquid> for <0-100%> intake without observable signs of aspiration. Long Term: Pt will: safely and adequately nourish and hydrate self on diet level/LRD with no s/s of aspiration. safely tolerate PO intake/diet level as primary source of nutritional needs improve safe and effective swallowing skills with least restrictive diet 11 Improve and maintain safe and effective swallow function have safe and efficient swallow of regular consistency diet and thin liquids. COGNITION Cognitive-linguistic Therapy Orientation, memory groups Current events (newspaper/daily events & discussion) Problem-solving Safety decision-making Reasoning Sequencing Verbal expression Sentence completion Music therapy Open-and closed-ended questions Naming, categorization Voice, fluency, articulation, etc. Communication aides/boards Compensatory training Auditory comprehension/receptive language Following directives/commands “wh” questions organizing/processing information with use of maps, puzzles, games, etc. Categories yes/no questions abstract thinking visual/logical solutions/scanning Numbers written communication compensatory training Tara Reed Courville, MCD, CCC-SLP & Lisa Young Milliken, MA, CCC-SLP The Alzheimer’s Association has developed the following “Ten Warning Signs”: 1. Memory changes that disrupt daily life. One of the most common signs of Alzheimer’s, especially in the early stages, is forgetting recently learned information. Others include forgetting important dates or events; asking for the same information over and over; relying on memory aids (e.g. reminder notes or electronic devices) or family members for things they used to handle on their own. What are typical age-related changes? Sometimes forgetting names or appointments, but remembering them later. 2. Challenges in planning or solving problems. 12 Some people may experience changes in their ability to develop and follow a plan or work with numbers. They may have trouble following a familiar recipe or keeping track of monthly bills. They may have difficulty concentrating and take much longer to do things than they did before. What are typical age-related changes? Making occasional errors when balancing a checkbook. 3. Difficulty completing familiar tasks at home, at work or at leisure. People with Alzheimer’s disease often find it hard to complete daily tasks. Sometimes, people may have trouble driving to a familiar location, managing a budget at work or remembering the rules of a favorite game. What are typical age-related changes? Occasionally needing help to use the settings on a microwave or record a television show. 4. Confusion with time and place. People with Alzheimer’s can lose track of dates, seasons and the passage of time. They may have trouble understanding something if it is not happening immediately. Sometimes they may forget where they are or how they got there. What are typical age-related changes? Getting confused about the day of the week but figuring it out later. 5. Trouble understanding visual images and spatial relationships. For some people, having vision problems is a sign of Alzheimer’s. They may have difficulty reading, judging distance, and determining color or contrast. In terms of perception, they may pass a mirror and think someone else is in the room. They may not realize they are the person in the mirror. What are typical age-related changes? Vision changes related to cataracts. 6. New problems with words in speaking or writing. People with Alzheimer’s may have trouble following or joining a conversation. They may stop in the middle of a conversation and have no idea how to continue or they may repeat themselves. They may struggle with vocabulary, have problems finding the right word or call things by the wrong name (e.g. calling a watch a “handclock”). What are typical age-related changes? Sometimes having trouble finding the right word. 7. Misplacing things and losing the ability to retrace steps. A person with Alzheimer’s disease may put things in unusual places. They may lose things and be unable to go back over their steps to find them again. Sometimes, they may accuse others of stealing. This may occur more frequently over time. What are typical age-related changes? Misplacing things from time to time, such as a pair of glasses or the remote control. 8. Decreased or poor judgment. People with Alzheimer’s may experience changes in judgment or decision-making. For example, they may use poor judgment when dealing with money, giving large amounts to telemarketers. they may pay less attention to grooming or keeping themselves clean. 13 What are typical age-related changes? Making a bad decision once in a while. 9. Withdrawal from work or social activities. A person with Alzheimer’s may start to remove themselves from hobbies, social activities, work projects or sports. They may have trouble keeping up with a favorite sports team or remembering how to complete a favorite hobby. They may also avoid being social because of the changes they have experienced. What are typical age-related changes? Sometimes feeling weary of work, family and social obligations. 10. Changes in mood and personality. The mood and personalities of people with Alzheimer’s can change. They can become confused, suspicious, depressed, fearful, or anxious. They may be easily upset at home, at work, with friends or in places where they are out of their comfort zone. What are typical age-related changes? Developing very specific ways of doing things and becoming irritable when a routine is disrupted. Overcoming Challenges Language, hearing or vision problems as well as low levels of health literacy may present obstacles to effective communication. Providers should take the following issues into account for both individuals and family. • A person with dementia may sometimes require more time to process information and may take longer to respond to a question. • Short sentences, visual cues or pictures may help the person with dementia understand what he or she is hearing. Hearing loss is very common in older adults and is often undiagnosed. • Determine if the person with dementia or the family caregiver has difficulty hearing or seeing. Do they require a hearing aid or eyeglasses? Are those items being used and are they effective? • Some people may not be “health literate.” They may need help to understand some health concepts, terminology, or the implications of treatment options. When health literacy is low, simple verbal explanations may be more effective than written information. The Language of Behavior All behaviors, including reactions to daily care, are a form of communication. The direct care provider is responsible for interpreting and responding to behaviors. For example: • A person repeatedly refusing a certain food or beverage may mean he or she does not like it. Simply changing the item may eliminate this behavior. If it persists, it is possible that the person has trouble swallowing. This may require a feeding swallowing evaluation. • A person who resists getting dressed may be in pain due to arthritis. Controlling for pain and/or minimizing physical movements that cause pain can address this behavior. • A person who seems to misunderstand a lot or does not respond when spoken to may have hearing loss. Proper care and use of hearing aids or other recommended assistive 14 listening technology is important. • A person who resists a bath may feel under attack when someone tries to help take off clothes. (Alzheimer’s Association) Resident characteristics contributing to food and fluid intake include cognitive status (Young, Binns & Greenwood, 2001), ability to eat independently (Kayser-Jones & Schell, 1997) physical limitations, difficulty swallowing (dysphagia; Steele, Greenwood, Ens, Robertson, & Seidman-Carlson, 1997) care provision with up to half of residents requiring assistance (Priefer & Robbins, 1997), including monitoring, verbal encouragement, and physical assistance (Van Ort & Phillips, 1995; Kayser-Jones & Schell). Environmental characteristics contributing to adequate intake include food quality, absence of environmental distractions (e.g., noise), and noninstitutional features (e.g., tablecloths) *** Residents monitored by staff during mealtimes are significantly less likely to have low food and fluid intake. Similarly, even after adjustment, residents having their meals in public dining areas are much less likely to have low intake relative to those in their bedrooms. Attention Strategies to help attention Self awareness. Learning to be aware of your current level of attention, concentration, and fatigue can help you know when to attempt tasks and when to take a break. One way to do this is to create a scale from 1 - 10, with 1 representing total relaxation, and 10 representing total stress and exhaustion. When you are about to attempt a task, look at your scale, if you score yourself between 1 and 3, you are probably ready to achieve things. If you score between 4 and 6, you can probably manage completing a short and easy task. If your score is higher, it is probably appropriate to take a break and attempt any tasks later. “Internal distractions” can also have an affect on attention. These are feelings such as stress or depression which will occupy your mind and distract you from a task. It is important not to attempt tasks that require a lot of concentration when you have internal distractions. Some people tell themselves that they will allow time later to think about things that are bothering them so that they can focus on the task at hand. If you feel anxious about completing a task, write down what worries you, and you will often find that your fears are unfounded. Write down rational responses to irrational fears. Build your confidence. Aim for progress rather than perfection when attempting a task. If the task seems too big, make a plan that is specific and break it into small steps, giving yourself a break after each step. If things go wrong try not to criticize yourself, just take a break and then attempt the task again, one step at a time. Congratulate yourself when you have completed a task. Planning. Planning and writing down a task can make it seem a little easier. 15 Write down the steps, include your brain breaks and your reward at the end. If things do not go to plan, know that you can stop and re-attempt the task tomorrow. If there are lots of jobs to do, prioritize and don’t overload yourself. Agree to complete 2 or 3 small tasks each day. Be Flexible. Remember, be flexible, if things are not going as planned, stop and re-plan, or just have a break and do something else. Stay on track. It can be easy to become distracted especially if the task is mundane. Staying on track with mundane tasks is difficult for everyone. There are a number of things you can do to help you complete the task. Divide up a mundane task and do a bit every day. Give yourself a list of affirmations such as “I can do this”, “keep going”, “let’s get this done”, to motivate yourself. Promise yourself a reward when you complete the task. Monitoring your fatigue. This is probably one of the most important strategies we can use. Many people with brain injury suffer higher levels of fatigue than normal and must be aware that fatigue will have a major impact on attention capabilities. Consider your environment. When you are trying to attend effectively in an environment that contains many distractions it is unlikely that you will be effective. Reduce noisy distractions such as TV, radio or other people talking. If your environment is cluttered and messy, try and tidy things up a little. Working in a clutter free environment is easier than working in a messy one. Allow plenty of time to complete tasks. Eliminate distractions. When there are distractions, try and decide how best to manage them. Decide what the distractions are and how you can change them e.g. if you want to talk and it is too noisy in a certain room because of the TV, you can either turn off the TV or go to another room to talk. If you cannot change the environment then try and move to a new environment. If you are unable to complete a task because of distractions, write it down your task and attempt it again later. Develop Systems. As with other cognitive difficulties caused by brain injury it is advantageous to develop systems such as checklists and reminders which take the load from your attention skills Brain Breaks. Set time periods for tasks and then have a “brain break” before continuing. You can use alarms to prompt you. Some people use alarms on their mobile phones. Health. Looking after all aspects of your general health will help you perform better on a daily basis. The 4 main areas to be aware off are Nutrition, Sleep, Exercise and Relaxation. Make sure you have a well balanced and healthy diet and stay well hydrated. Make sure you have a regular and sufficient night time sleep, as well as sleep breaks in the day if needed. Try and do some exercise every day to stay reasonably fit. Relaxation is sometimes overlooked, but contributes to a positive and healthy lifestyle. Everyone relaxes in different ways, but it is important to find some time everyday to get away from your stress and worries. Going for a walk, meditating and yoga are all good ways to relax. Reading is often difficult following a brain injury. Try to read when you feel at your most attentive. Try not to Multi-task. Focus on one task at a time. Trying to multi-task may mean that you achieve nothing or make a poor attempt at everything. 16 If you have to divide your time between 2 tasks try and do one task that relies on mental concentration and one task that is physical e.g. listening to the radio while cleaning the sink. If you are switching between tasks, try and take a small break between switching to give your brain time to adjust. Some people find it helpful to say aloud what they are doing when they change tasks to help them stay on track. Listening to, and following conversations sometimes requires lots of mental energy. Try to self monitor so that you are aware when your attention is beginning to falter. Try and repeat important points in your head. Pick out the key pieces of information and disregard the non-important stuff. Develop active listening skills to manage conversations: - Clarification - requesting extra information or repetition - Probing questions - ask questions to gain further information - Paraphrasing - this allows the listener to make sure you understood - Summarizing - pulls together key points and concludes the topic Quick Checklist for Attention Skills following Brain Injury Learn to be self aware and monitor your level of attention Monitor your fatigue and schedule in breaks Allow plenty of time to achieve tasks Make a plan and break your task into small steps Adapt your environment to eliminate distractions ·Evaluate and monitor distraction before starting a task Be flexible - stop, re-plan, or reschedule if you need to Develop systems of alarms and reminders to keep focused Manage internal distractions If you are anxious, write down your fears Try and attempt one task at a time Allow yourself “brain breaks” between tasks Congratulate and reward yourself when you have completed a task Health - nutrition, sleep, exercise and relaxation Self monitor during conversations Try and use active listening skills during conversations Make other people aware of your difficulties Icommunicatetherapy.com 17 Executive Functioning (initiating, carrying out, and completing tasks effectively and successfully) There are a number of processes to completing a task successfully. Firstly we will discuss the steps to completing a task and then we will focus on strategies to facilitate this process: Have an awareness that a task requires initiation. If you do not have an awareness that you are running out of food, you will not initiate a trip to the supermarket. Plan the task. Break the task down into steps, make a list. Initiate the task. Start the task and follow it through. Manage any unplanned difficulties that occur. Complete the task. Review how the task went and think about any changes you need to make, so that the task is easier next time. Icommunicatetherapy.com GOAL Pt will…. TARGET HOW TO Increase thought organization to 80% proficiency. Increase sequencing for 3 step tasks/3 items to 80% proficiency. Increase attention to task to (minute range) for 3 consecutive sessions. Attention Increase auditory comprehension of spoken langue to 80% proficiency. Auditory comprehension Impaired attention--reinforce client for paying attention (Hegde, Davis 2010) Auditory comp of spoken language-- first ask clients to point to named pics/obj/body parts. Ask y/n questions. Then, ask for correct responses to phrases and sentences. 18 Ask to follow instructions. (Hegde, Davis 2010) Fxl reading comprehension target basic skills for every day functioning (reading a newspaper) (Hegde, Davis 2010) Increase memory for daily routines utilizing external cues with 100% proficiency. Memory for daily routines prepare lists of daily routines and written signs and instructions (Hegde, Davis 2010) Increase orientation to time, place, and person to 100% across 3 consecutive sessions. Orientation Increase verbal expression to 7/10 words/names/actions for ADLs to promote independence Verbal expression Design questions testing orientation (where are you now? What time is it?) (Hegde, Davis 2010) select names of objs/persons/actions that are immediate use to client. Synonyms, antonyms, rhyming, spelling, completing sentences. Increase fxl reading comprehension to 80% accuracy Increase verbal expression to phrases and sentences in 7/10 responses. requests, commands, demands, wh questions, y/n questions. (Hegde, Davis 2010) 19 Answer y/n questions related to <complexity> information with <0-100%> accuracy with <cue type> to understand caregiver requests. y/n questions Verbally demonstrate comprehension of object function with <0-100%> accuracy with <cue type>. Word finding/obj ID Increase fxl abstract reasoning abilities for ADLs to 80% proficiency Abstract reasoning Follow <1-3> step commands with <0-100%> accuracy with <cue type> to understand <purpose> Following directions <explain, follow> safety strategies for ADLs with <0-100%> accuracy with <cues>. safety Abstract reasoning-teach correct inferences draw from read or narrated stories. Includes absurdities, proverbs/metaphors. (Hedge, Davis 2010).

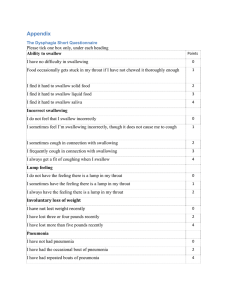

![Dysphagia Webinar, May, 2013[2]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005382560_1-ff5244e89815170fde8b3f907df8b381-300x300.png)