房曼琪 - Mira Fong

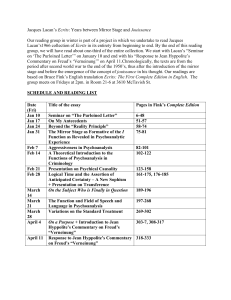

advertisement

1 NAGARJUNA, SARTRE AND LACAN THE CONTINGENCY OF THE SELF MIRA FONG 房曼琪 2 "Never in the thought of the West has the Self been so pervaded by negation. One would have to go to the East, to the Buddhist philosopher Nagarjuna with his doctrine of Anatman (no-self), the insubstantiality of the Self, to meet as awesome a list of negations as Sartre draws up. The Self, indeed, is in Sartre's treatment, as in Buddhism, a bubble that has nothing at its center." Irrational Man by William Barrett A Negative Ontology of the Self Nagarjuna 龍樹論師, the foremost scholar of the Mahayana School and was revered as the second Buddha, who articulated the doctrine of emptiness, aimed in the deconstruction of Essentialism. His argument, regarding the contingency of the self and the existence of the phenomenal world, was further elaborated, after two thousand years, in the existential analysis of Jacques Lacan and Jean Paul Sartre. The principal motif of this paper is to correlate their analysis of the self with references to their own propositions including the ideas of emptiness 性空 (Nagarjuna), nothingness 虛無 (Sartre) and the lack 依性空 (Lacan) as these are the foundations in which they construct the insubstantial and indeterminate character of the self. Each of the three thinkers conducts a critical theory on the self by eliciting a particular hermeneutics, either from a Buddhist or psychoanalytic perspective. They seem to have reached the same understanding that the self has no underlying substance. Rather, the self is a terrain of composites 六識六境 and its consciousness and identity co-arise 緣起 with the world. Such assertion is tied to Nagarjuna's key theory of dependent origination 依他起性 , which is investigated in great details in the context of psychoanalysis by Sartre and Lacan. While Nagarjuna advanced his arguments by utilizing a progression of dialectic logic to demonstrate the fictitious nature of the self 破相顯性, Sartre's phenomenology and Lacan's structural psychoanalysis formulated a negative ontology to uncover the precondition of the self. Here, negative ontology means the self is treated on a phenomenal plane. Sartre observes that man's existence is marked by nothingness 空無, "a being who is not what he is and is what he is not". Lacan, a postmodern theorist, views the self, lacking a unified identity. It is rather fragmented and conditioned by cultural discourses. Additionally, both Sartre and Lacan depict the antagonistic and dependent nature of the human psyche with reference to Hegel's "life and death struggle of the self and the other" which can be compared as a Western version of dependent origination. Nevertheless, one must keep in mind that, as a philosophical construction, there remains fundamental differences between their work; each was a response to its own historical circumstance. In the case of Nagarjuna, his epistemic deconstruction of the self by taking an opposing stand against the metaphysics of the Hindu system which 3 postulates a universal Selfhood, the Atman or Brahman. He also rejects the doctrine of the early Buddhist schools of his time as they regarded the self as having its own existence (svabhava, a substantial real). For Sartre, the emphasis on freedom and action was to counter the pervasive nihilism during WWII. With a Nietzschean defiance, he contends that there is no creator and one must invent its own authentic self within the condition of nothingness. Lacan, an anti-orthodox rebel who supported the French Communist Party to fight against the capitalistic practice, tackled the gap between the Freudian ego and the sovereignty of the establishment. My attempt to draw a connection between their negative ontology of the self and the psychology of dependent origination could perhaps risking a misinterpretation. Nonetheless, in a deeper level, their investigation of the fundamental conditions of human existence, its suffering and transcendence, is universal. In the Buddhist scripture, Sati, as pure awareness, could be achieved when one understands the nature and cause of suffering (the five aggregates of attachment and the five mental obstacles). Lacan and Sartre's analysis, though without any reference to Buddhism, offers insights relevant to the Buddhist notion regarding the three marks of existence, that is, impermanence, discontent and no self. They all stress the social dimension of desire or craving as the cause of suffering. The added Chinese phrases taken from Buddhist texts (for those who also read Chinese) are intended to expand the contextual meanings as well as cultivating a transitioning from Lacan's multi-layered analysis to the way of Zen. Nagarjuna (c.150-250): The Radical Indeterminacy of the Self "If there is no essence, who could become the other? If there is essence, what could become the other?" Nagarjuna In refuting Descartes' claim that the mental substance is indubitable, David Hume, a Scottish empiricist, argues that the cogito, the thinking substance, is composed of memories, impressions and concepts. They are mental concepts determined by the principle of contiguity, the relational conjunction of ideas. Hume's radical skepticism accords with the central tenet in Nagarjuna's teaching that our knowledge of the self and reality is fallible. Although both argue from a causal point of view, but causality, for Hume, is constituted by constant conjunctions, itself is not a principle or self-evident truth. Nagarjuna's major work, Madhyamika 中觀論, is a systematic and rigorous analysis of the status of the self through the concept of sunyata (emptiness 性空). His aim was to counter the realistic view of the self and its perceived phenomenal world 森羅萬相. He asserts that the idea of a coherent, independent self is an illusion 假相 since its genesis is pervaded by sunyata. All things come into existence by their relations with others and 4 are mutually dependent, linked by a causal nexus 因果相續, meaning a process of differentiation. To the questions of "who I am" and "what I am", Nagarjuna's answer is that the self, as a cognitive agent, is a mere collection of mental and physical aggregates 積聚, such as sensory impressions and mental concepts, "A self under its own power is non-existent because the aggregates are not the person. " Hume also made similar remark, "Man is a bundle of collection of different perceptions with succeed one another with inconceivable rapidity and are in perpetual flux of movement". What they both are saying is that the self and the knowledge of the world (names and forms), is without inherent substance (svabhava 實性) and is temporal in nature. What one takes to be real and objective regarding the existence of the self and the world is merely a hypothesis as they it is invented by thought. Nagarjuna proclaims,"No things whatsoever exist, at any time or place, having risen by themselves, from another, from both or without a cause." The concept of sunyata is intended as an internal negation to dismantle any false apprehension of a singular and substantial self. It plays a key role in Nagarjuna's system, the Madhyamaka School, which rejects the postulation of a universal Self or the Atman, since it can neither be logically inferred, nor verified by a posteriori judgment. In The Treaties of Twofold Truth 二諦論, Nagarjuna conducts a dialectic method of reasoning by differentiating the two levels of truth 真俗二諦, "One is that of a personal and conventional truth of the self, and a higher truth which surpasses it. " 中觀論: 諸佛依二 諦, 為眾生說法, 一以世俗諦, 二第一義諦. 說諸法由因緣 , 緣起而有者, 俗諦. 說一切畢竟空, 真諦也. The first level truth 世諦, the thesis, is established by social agreement or public opinion for pragmatic reason. The second level truth 真諦, as an antithesis with a skeptic position, regards all truth claims are provisional. 吉藏 三論玄義: 說有為俗諦, 空為真諦. 有空為俗, 非有非空為真之二諦... 言亡慮絕為真之二諦. Nagarjuna purports sunyata to the theory of no-self (anatman 性空) and of dependent origination 依他起性. The epistemic application of sunyata 析空 is to explain the misconception of reality but not to be taken as an absolute truth. Such clarification is well explained by Hsueh-Li Chen in Nagarjuna, Kant and Wittgenstein, "Nagarjuna's rejection of the concept of noumena does not imply that he accepted the legitimate use of human categories or concepts in the realm of phenomena " 內止其心, 不空外界. Basically, Nagarjuna is saying that ideas are merely products of the mind 假名 and are determined by a dialogical system. To borrow Lacan's words, "Every truth has a structure of a fiction." 5 Nagarjuna proclaims that our ideas of things are established in virtue of its opposite 二 見分, such as the notion of being or non-being 空有問題. He explicates, "That which is the element of light is seen to exist on account of darkness, and the element of good is seen to exist on account of bad, that which is the element of space is seen to exist on account of form." The Treaties of the Middle Way 中論, Nagarjuna's major theoretical framework, addresses the idea of the self and the world is based on a dichotomous thinking ( by way of paired opposites). The way to transcend the either/or mentality, he proposes, is to cultivate a non-abiding awareness 言慮無寄, that is, the practice of the middle way. It is a rigorous method of progressive negation to any truth claim as he argues, "There is no arising, no dissolving 不生不滅, no atman and no anatman 無我亦 無無我." Basically, the Middle Way aims to develop one's higher cognition (pragna), to see the limitation of conceptual thinking thereby transcends opposite statements of existence. It alludes to a non-fixated approach in order to transcend both negation and affirmation 言詞相寂, 文字性空, that is, between nihilism and essentialism. Some scholars compare Nagarjuna's logic of deconstruction to that of Postmodern theory which rejects the idea of universality and replaces with an unstable world view of change and flux. Both claim that language plays a role in determine one's experience. Rather, they argue from a relativistic position that ideas are inferred by contrasting to other ideas 隨應諸法, 假實不定. To put it in a structural context, the meaning of a sign is understood in its relation to other signs within a system of signifiers. Interestingly, Wittgenstein's theory of the language game also implies the same notion that our ideas of things are provincial as they are limited within the framework of language game as well as a set of speech rules. In regard to the realm outside the language, Wittgenstein seems to pointing to the way of Zen which transcends language 言語道斷, 心行處減, as he ends his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus with these words, "Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent". Implicitly, Nagarjuna's dialectic meant to be a transitioning from critical thinking to a state of Bodhi mind 淵微鏡徹, the silent mirroring of suchness. His method was later assimilated into the Zen practice by way of non-verbal transmission 以教照心, 以心解教, as such state is purely empirical 非想,非非想處. Seeing things as they are 諸相寂然 without articulation. Overall, the basic premise of "The Middle Way", taken to a logical extreme, is to point out that what considered as matter of fact is constituted through relations of ideas 因緣 所生. Things in themselves neither have substances (svahbava) nor empty. Nagarjuna himself considers his own teaching to be tentative, a characteristic of Buddhist teaching. The purpose is to relinquish the constraint of an absolute or realistic position. Different level of discourse is required due to circumstantial factors 方便教化. 6 The Prajnaparamita Sutra 心經, the best known Buddhist text, contains Nagarjuna's core theory, the investigation of the conditions of arising, dwelling and finally the ceasing. Its content can be summed up in his words: What dependently arises Has no cessation, no production, no annihilation, no permanence No coming, no going, no difference, no sameness, Is free of elaborations of inherent existence and of duality And is at peace. One can observe a parallel and complimentary view of sunyata between Nagarjuna and that of Sartre and Lacan; they also relate the concept of the no-self to a lack 依性空 which is precisely the field of sunyata, described by Sartre, "Nothing comes into the world through man because man not only bears the nothing within him, but consists of nothing". Although there is a conceptual difference between the two; emptiness for Nagarjuna is an ontological statement whereas for Sartre, it associates with the unreality of self-identity. Contemporary Western philosophy puts emphasis on the social dimension of the self such as the study of Dasein in Heidegger's Being and Time. Dasein, as human being, is situated in temporality and constructed by its facticity, meaning its physical appearance, intellectual competence and social integration. It has no prior essence. In this respect, both Sartre's and Heidegger's existential phenomenology corresponds to Nagarjuna's theory that the consciousness of the self is not innate but co-arises with the phenomenal world 因緣所生. Jean Paul Sartre (1905-1980): The Poverty of the Self. The enquiry into the meaning and purpose of human existence in the climate of pervasive nothingness 泯絕無寄 became the prime concern since Kierkegaard. He asked, "I stick my finger into existence, it smells nothing. Where am I? What is this thing called the world?... Who am I? How did I come into this world? Why was I not consulted?" Since then, a new movement has emerged from Continental philosophy. Contrary to the classical question, "What can one know" in the pursuit of epistemological certainty, philosophers turned to the human subject to explore its inner pathos. This is the realm of phenomenology, a descriptive method developed by Edmund Husserl in the early 1900s. Instead of studying objects as independent entities, phenomenology investigates objects that appear in consciousness as it is always an intentional act. In other words, phenomenology studies the realm of conscious activities of one's experience including one's perception of things and the internal thoughts and feelings. They are treated equally as phenomena of a lived world (lebenswelt). One such endeavor is the publication of Sartre's Being and Nothingness in 1943. It was his way of 7 moving phenomenology toward the direction of human existence instead of studying the phenomenal world. Although both Sartre and Nagarjuna illustrate the unstable character of the self, Nagarjuna's argument relies on linguistic and logical operation; whereas Sartre's is phenomenological and his negation of the self (as being) is through the proposition of nothingness. While Heidegger was interested in disclosing the region of being, Sartre located one's being in social relationship. He came to realize that there is a negative mode within human consciousness and manifests itself as an intrinsic split 緣慮. Based on his observation, Sartre formulated a dualistic ontology, the dichotomy of being-in-itself and being- for-itself, a theory was originally introduced by Hegel. In Phenomenology of the Spirit, Hegel gives a dramatic account of the master and slave confrontation; each self must "struggle till death" in order to subjugate the other self. He writes, "The absolute object is the I individual, but when faced by another self-consciousness, difficulties arise (the other is a veritable mirror of my own consciousness). Each I must position itself against the other". Such antagonism was eagerly developed in both Sartre and Lacan's psychoanalytic theory. Sartre deconstructs the solidity of the self by internalizing the conflict of master and slave which he regards as the cause of self alienation. In Being and Nothingness, Sartre gives a detail explanation regarding the antagonism between being-in-itself and beingfor-itself. The category of being-in-itself refers to one's own facticity like object among objects. It also applies to objects in the physical realm which described by Sartre as lack of being (or becoming). On the other hand, being-for-itself is the conscious self or the subjectivity of one's being. Both are the ontological constituents of nothingness. The consciousness of being-for-itself experiences the world as a projection of its own possibilities or freedom through a "for-me" interpretation. And yet, such subjectivity can be objectified when one encounters the forces outside oneself. What this means is that when being-for-itself collides with the other, it risks the threat of being turned into a non-being, an object. Again, Sartre explains such a dynamic by referring to a master/slave psycho-drama, "The other, in a certain sense, is the radical negation of my subjectivity, he is the one for whom I am not a subject but an object". One's own sense of self can easily slip away by the interrogative look of others as "sitting in judgment". In this respect, the self is being reduced of its own possibilities by allowing "what-is-not determines what-is." The inherent split of human psyche also manifests itself in social and political conflicts between classes and nations. Similarly, Freud interprets such internal trauma as the cause of man's outward aggression in his Civilization and Its Discontents, "Man have gained control over the forces of nature to such an extent that with their help they would have no difficulty in exterminating one another to the last man." 8 Based on his observation that "to be is to be for another", Sartre added a third category, "being-for-others", which is an "otherized self", since part of one's being is always for others 緣起性空 in an attempt to escape nothingness, the absence of being. In other words, being-for-others has to do with the seeking of one's identity through others; thereby one is being objectified into "for-itself-for-others". Sartre's in-depth psychoanalysis of human relations and the troubled self is vividly illustrated in his play No exit, a literary interpretation of his magnum opus, Being and Nothingnes. Both were written in the same year. No Exit, in a theatrical format, plays out the psychology of "being-for-others" and "struggle till death" (except that all three characters in the play were dead already). In it, the three characters, Garcin, Inez and Estelle, are supposed to be dead and confined in a room(the realm of damnation). Each, as a chimerical self, is preoccupied with self identity by seeking validation through the oppressive others. One hears Inez's lament on the non-substantiality of herself, "How weak I am, a mere breath in the air, a gaze observing you, a formless thought that thinks you." After being emotionally tormented by the two women and unable to escape, Garcin concludes, "Hell is other people". Because the others are able to take away one's own subjectivity and making it an object of his world. Sartre professes, "Nothingness enters the world through human existence". What he meant is that human consciousness constitutes its own nothingness and yet, it is also a pre-requisite of freedom. Nothingness is experienced through a subjective consciousness. In Sartre's view, consciousness itself is basically empty since it exists only as "conscious of" some phenomenal entities. As a subjective mode, nothingness is the awareness of "what is not". What lies at the core of one's existence is a non-being (a void); it has no prior essence. As a negation, nothingness is dialectically generated when the "for-itself" moves toward its antithesis. In this respect, the self is divided by two opposing poles, being and nothingness. It is through man that nothingness comes into the world of beings as it co-arises with the consciousness of "for-itself". In short, nothingness simply means man's existence is a lack of being 本無. The notion of lack is further explored by another Parisian thinker, Jacques Lacan, in his analysis of the ego, desire and the Other. Sartre's investigation on the dependent nature of human desire is also an important subject for both Buddhism and Lacan. Sartre observes that desire is originated from a lack, "One looks at things with desire". Further, desire is always tied to one's memories, anxiety, fear, interests, needs and projects. In Being and Nothingness, Sartre stresses his point, "The existence of desire as a human fact is sufficient to prove that human reality is a lack". Desire and anxiety are caused by one's internal nothingness which is like a hole waiting to be filled, a view elaborated in his "Existentialism and Human Emotions, "I have only to crawl into it (the hole) in order to make myself exist in the 9 world which awaits me". In nothingness, man is propelled to seek its own density, like "The uniform and spherical plentitude of Parmenidean being." In many ways, Sartre's philosophy corresponds to the skeptic ideas of David Hume, an intellectual of mid-Eighteenth century who frequented the salons in Paris. Both thinkers reject the belief of a supernatural spirit, transcendent reality and a teleological universe such as Hegel's Geist, an invisible spirit behind the rational development of human history. Rather, they argue that there is no timeless principle that sustains human reality and the self. Contrary to Plato or Aquinas' theory of the immortality of the soul, Sartre compares the self to a blank canvas, a tabula rasa 空無所有 in which one must create one's own portrait. Furthermore, Sartre associates egotism with the project of becoming God (to cover up the lack of being). He remarks, "To be man means to reach toward being God. Or if you prefer, man fundamentally is the desire to be God...Every human reality is a passion in that it projects losing itself so as to found being and by the same stroke to constitute the In-itself which escapes contingency by being its own foundation which religions call God." Sartre makes it very clear that man's fundamental project, the construction of a transcendent Being in order to fill the void, is "A useless passion striving in a universe without purpose". Jacques Lacan (1901-1981): The I is the Other Jacques Lacan, a French Psychoanalyst and a contemporary of Sartre of the 1950s, is perhaps one of the most intriguing continental thinkers. Apart from his reworking of Freud's theory of the ego and the unconscious, Lacan formulates a pluralistic and negative ontology by incorporating ideas from a diverse group of thinkers, primarily, Hegel, Heidegger, Saussure and Levi-Strauss. Lacan was also active in the Parisian artistic and literary circle, particularly, the surrealist group. From Hegel, Lacan adopted his dialectic reasoning to invert the Platonic Real to the unreality of the self 性空. The diversity of Lacan's theories, regarding the genesis of the self and its culturalization, is influenced by the social anthropology of Claude Levi-Strauss (the analysis of the basic kinship system of different societies and culture instead of specific ideology/world view) as well as Ferdinand De Saussure's structural linguistics (language as a system of signs and signification. Signs are understood in relation to each other and to the system), through which Lacan developed his own notion of the self within the framework of the three orders. Contrary to the practice in general psychology which aims to integrate the ego, Lacan, by way of structural analysis, de-centers the Freudian ego. The self, in his view, is predicated by language and has no intrinsic properties. Rather, it is something of a lack 依性空; its meaning is derived from a chain of signification. Beyond language, the world is inaccessible to the cogito. Lacan transfers the Freudian ego to a structural theorizing, a similar task conducted by Nagarjuna. Both argue that the idea of the self is derived 10 through a process of differentiation 分別性. According to Lacan, the self, as a signifier suspended in the linguistic plane, has no access to the thing-in-itself. His argument goes like this, "The signifier is a sign that does not refers to any object...it refers to another sign which is as such structured to signify the absence of another sign " 無盡緣起. Lacan sees the self is bound up in the tension between its own fragmentation and the imaginary ideal as to be unified and coherent. The self, for Lacan, has two components, the social/cultural as well as the linguistic. On the social plane, the content of the self is pre-determined by an existing value system. On the linguistic plane, the self as a speaking entity, its status is identified as a signifier. As a young doctor in the 1930s, Lacan was influenced by the pro-left surrealists, in particular, the painter Salvador Dali's view of the free flowing of the unconscious. Lacan agrees that the human subject is not a rational construct but rather deficient, lacking identity and is driven by desire. His investigation of the self as the subject is a radical departure from Descartes' view of the human subject as a rational being. Descartes' cogito, the thinking substance and an anchor for epistemology, is capable of acquiring universal knowledge through reason. On the contrary, Lacan's subject is neither rational nor immaterial. He reverses Descartes cogito from "I think therefore I am" to "I think where I am not, therefore I am where I do not think." For Lacan, the subject is an unreality and has no interiority 空境. It inheres its content from outside as Bruce Fink differentiates in The Lacanian Subject. He explains, "The Lacanian subject is neither the individual, nor the thinking subject... " further: "Temporary speaking, the subject appears only as a pulsation, an occasional impulse or interruption that immediately dies away or is extinguished " 眾緣合即有. One find such characteristic of the subject similar to the Buddhist view 一切諸法, 皆同幻化 as Fink further comments, "Eastern philosophy has been telling us for millennia, a construct, a mental object." Lacan's principal theory is a tripartite structure composed of three orders (as co-arising 相應俱起), the Imaginary (unaware of the unreality of its content), the Real (which is an absence) and the Symbolic (language is the prime element). Among the three orders, the Symbolic as a moral framework, is sometimes referred to the term "The name-of- thefather". It regulates the subject's conscious and unconscious activities. It is internalized as soon as the subject enters the human community. The Symbolic precedes the other two orders and is generally referred to as law and social convention. Lacan associates the Symbolic plane with the Big Other (the cultural super-ego) which refers to language and the Symbolic fabrics. Within the tripartite structure, the self is adventitious. It is conditioned by the Symbolic Order, a universal totality which Lacan describes in Ecrits (1966), "It covers all human lived experience like a web...it is always there, more or less latent." Inevitably, such totalizing power generates tension for both the Imaginary and the Real which is almost 11 absent since the three orders are interwoven 因緣相生. Lacan proclaims, "The unconscious is structured like a language". What he meant is that the unconscious of the subject is taken over by the discourse of the Other. Under the sovereignty of the Symbolic Order, the Imaginary self is a false self identity of "Who I think I am". It survives through bad faith meaning one is indoctrinated by social propagandas. Such self-delusion is dramatized in Eugene O'neill's classic play, The Iceman Cometh. It is a story of a collection of characters harbor together in a place called Harry Hope's Salon. Each lives in his own fantasy, the Imaginary realm. Their day to day existence is by hanging on to a pipe dream which is really a hopeless hope. Until one day, they are confronted by a messianic figure, Hickey, who represents the terrifying truth. That is, one must confront one's own self-delusion which is made up with desires and borrowed self-identity. As for the Real, it is hidden and knotted together with the Other, described by Lacan as the Borromean knot. Lacan distinguishes the Real as outside the language and cannot be symbolized except with occasional breakthrough 隱顯, like tearing a hole. The only possibility for the Real to unveil itself and claim its being is by subverting the Symbolic Order all together (this suggests Lacan's political activism, the attempt to undermine Capitalism). In other words, the Real must confront between being and its own vacuity since its space is occupied by the Symbolic Other. This is exactly the message that Hickey, in The Iceman Cometh, brought to those who live in the Imaginary realm. Like Sartre, Lacan, in his early work, also examines one's psychological need for confirmation through others by referring to Hegel's master and slave dynamics. The servile relation of self and Other plays out as Hegel describes, "On approaching the other, it has lost its own self, since it finds itself as another being." It implies that one's identity is unconsciously concealed in the other. Lacan equates the self/other dichotomy to the subject's encountering of the Big Other. He sees it as an intrusion to the Real that occurs during the ego's early psychic development. Thus, he re-describes Hegel's dialectic to "A struggle for the others", that is, "Le desir de Autre, man desires what the other desires". The self wants to be desired by the other (as portrayed in Sartre's play, No Exit, each desires the other for his or her own redemption). Perhaps the most significant contribution of Lacan's work is his insight on the social dimension of desire 遍計所執. Lacan tackles Freud's pleasure principle by introducing two key concepts in his later work, namely "Objet a", the object cause of desire 痴障" and "Jouissance", pleasure in pain 驅心役識". The concept of Jouissance was first introduced in his seminar The Ethics of Psychoanalysis 1959-1960. It refers to a paradoxical reaction of the subject's intention as it constantly tries to transgress the prohibition 貪欲, 12 to find pleasure in its lack of enjoyment. Hence, it is more of a suffering than pleasure 苦 樂二受. "Objet a" denotes a non-specific object of desire. Rather, it is the cause of desire, the desire to be desired by the Other. In other words, desire is not related to its object but to a lack. According to Lacan, "Object a" is a surplus of Jouissance, a psychological state in which Jouissance becomes obsessive as the ego imagines and experiences its own existence through the antagonistic relation of self and other. Lacan gives his take on "Object a", "What makes an object desirable is not any intrinsic quality of the thing in itself but simply the fact that it is desired by another." Objet a is a corollary with the empty experience of Jouissance, because it is essentially empty. Given the fact that desire is always followed by suffering 生苦為業, Lacan, a theorist, endeavors to get to the deeper layer by differentiating between Jouissance and desire. It is well explained by Jeanne Wolff Bernstein, "Lacan linked and contrasted jouissance with desire. Whereas desire implies a lack-one can only desire what one does not have, jouissance implies an excess of gratification, readily turning its pursuit of pleasure into an abyss of tension and pain." In his article Kant with Sade, Lacan continues to elaborate the dependent and causal character of desire 情執, "Desire must be formulated as the Other's desire (desir de L'Autre) since it is originally desire for what the Other desire." One's unconscious desire is tied to the desire of the Other since the I and Other are co-arising. Hence Lacan concludes, "The I is the Other, Je est un autre." Like Sartre, Lacan also attributes desire to a lack (a lack of being). Conversely, the lack leads to the surplus of desire in a vicious cycle. For this reason, Lacan disagrees with Freud's suggestion of liberating the unconscious because it too operates within the symbolic order. Lacan also considers the conventional psychoanalytic model is, in fact, a reinforcement of the unreal self 假相 along with its pathos 本惑. He regards the attempt to unify the individual psyche or the split ego as practicing "human engineering". It actually intensifies the ego's narcissistic impulse by postulating an ideal self which can further create a rift between the I and other. Such antagonism and idealization have been playing out in endless human dramas 恆沙煩惱 (as brilliantly portrayed in all Shakespeare 's plays). Instead of finding a cure, Lacan suggests a conscious effort to dissolve the subject's illusion of the self 斷惑減苦. Essentially, Lacan is not saying anything different from the Buddhist perspective that desire, haunted by its own insatiability 妄執, is the basic condition of human existence. Lacan's comprehensive theorizing operates on several different levels simultaneously by incorporating linguistics, psychology, literature and art. Behind the Lacanian hermeneutics, there is a connection to the core teaching of Nagarjuna; both are non- 13 essentialist and regard the self as indeterminate and contingent. The idea of "dependent origination 依他起性" corresponds to Lacan's portraying of the subject as an empty signifier. It loses its certainty in a signifying process 遷流相續. More importantly, his insights on desire 妄執 as the cause of suffering is fundamental to Buddhism 苦諦. 5. Project of Freedom Although the three thinkers appear to have painted a nihilist view of human condition at the brink of nothingness; such deconstruction itself meant to be a way of relieving suffering by way of dismantling the self 破相. Nagarjuna compares the illusion of the self to that of a magical performance, or reflections from a hall of mirrors. David Hume also made a similar remark, "The mind is a kind of theater, where perceptions successively make their appearance, mingled in an infinite variety of postures and situations." The way Nagarjuna conducts his extreme logic in Madhyamika can be regarded as a training method 分別所分別 to free the mind from clinging to names and forms 恆審思 量 as if they are real. For instance, the concept of sunyata, taken as either negative or otherwise, is still a mental construct. It is nothing but a name, lacking its own reality. The implication of sunyata depicts a revelatory possibility 蘊空 outside the bound of language. Within the world of samsara, the realm of suffering and perpetual wandering 苦輪常運, lies the possibility of mukti, an enlightened mind 正覺. Nagarjuna refers such becoming to Buddha's own journey of liberation. The investigation of nothingness 如虛 空之包藏萬有 opens to a path of transformation 真空妙有. As Heidegger amuses, "Das nichts selbst nichtet, nothingness makes nought!" Influenced by Kierkegaard, the freedom project for Sartre takes the form of an eruptive force. He declares, "Man is what he makes of himself". The word "authenticity" has its Greek root, meaning to make or create oneself. As an intellectual revolutionary, Sartre's self creation is linked to the ethics of authenticity. Despite the fact that the human agent is contingent and the self is only a convention, Sartre's counter polemic is that the self can be experienced as "the presence to self". Against the backdrop of an indifferent universe, the freedom project is to surge up from the void 空境 and to reinvent one's life through active self-determination. In contrast to Hegel's attempt to re-enact Plato's transcendental Eidos by inserting the absolute consciousness within the human history as the guiding spirit, Sartre sees man's overall condition is nothingness and thereby proclaims, "Man's essence is freedom". The posit of nothingness is the basis of freedom; it allows man to define himself by action. Sartre's Being and Nothingness paves way to affirmative action as explained by William Barrett, "The only meaning he can give himself is through the free project that he launches out of his own nothingness. Sartre turns from nothingness not to compassion, 14 but to human freedom as realized in revolutionary activity." Far different from other continental thinkers (the analytic, hermeneutic or phenomenological), Sartre's existential stance was "the philosophie engagee". Similarly, Nagarjuna, a political reformer of his time, also gives priority to personal action for a higher cause over a contemplative path 成大悲則不住 涅槃. In his less pessimistic writing Existentialism and Human Emotions (1946), Sartre moves from a negative ontology to an ethical plane which emphasizes freedom and action. Why? Because one's being is located in its existential dimension and is historically and politically situated. Thus freedom is to be exercised "only in the ethical plane". Sartre gives his reason, "When we say that a man is responsible for himself, we do not only mean that he is responsible for his own individuality, but that he is responsible for all men." Obviously, Sartre's freedom is predicated by an ethical precept since the individual is part of the larger phenomenon of being. It's up to the individual to define who he is and not escaping into a "Bad Faith" which is a form of self-deception. One is to rise above the antagonistic existence 無礙 by cultivating an empathetic understanding 真心全體. This is self-transformation. The answer in which Lacan comes up with, in order to relief the trauma of the self, is as radical as Nagarjuna's, that one must be resolute in confronting the sunyata of the self 性空 and the unreality of the Other 別相. Jeanne Wolff Bernstein explains such confrontation, "One's subjectivity was constructed through and for an Other...and forced to confront both the void of the Other and the void inside of himself..." Some of Lacan's ideas may appear to be inconsistent when he integrated the three orders into a meta-theory including the science of mathematics and logic. Nevertheless, he continued to tackle the notion of the Real and its resistance to the established order. It is interesting to note that Lorenzo Chiesa's comment in Subjectivity and Otherness regarding Lacan's reassessment of the Real and its demarcation from the Other, "All we are left with is the Real-of-the-Symbolic and a mythical extrasymbolic "undead". ..Lacan also unintentionally falls back into a quasi-mythical understanding of the pure Real by promoting the notion of a transcendental real "Thing" understood as a positive absence." The statement reveals an ambivalent status of the Real as "The undead". Though absent, it has the possibility for further explication through a nonverbal surfacing, from the surreal to the real (Lacan participated in the early French Surrealist's movement and was a close friend of Andre Breton) and perhaps, mixed with a bit of Zen. Lacan's anticipation of the Real seems to coincide with Heidegger's meditation on being since Lacan translated his work into French. According to Heidegger, Dasein is "being thrown" into a world of Das Man, the They, which he refers to as social norms and linguistic convention. Such interpretation coincides with Lacan's notion of the big Other. 15 Das Man, says Heidegger, "Prescribes one's state-of-mind and determines what and how one sees". One can further relate Dasein's throwness to the traumatic entrance of the Real into the Symbolic plane. This explains why both Heidegger and Lacan insist that the way to uncover one's authenticity (one's authentic mode of being) or the absent Real is by questioning the whole establishment through which one is taught to think. One may further implicate Lacan's elusive Real 隱顯, the pre-symbolic subject, with Heidegger's portraying of the inexpressiveness of Being 離言直顯 which resembles a non-conceptual state of suchness 体性現起. In fact, they both were interested in the contemplative approach 觀照 of Eastern philosophy. Lacan characterizes the intrinsic resistance of the Real as an eruption which he described "As a knock on the door that interrupts a dream"先有大覺 而後覺此大夢. One can compare such eruption to a sudden awakening. The self is seen as reflection of the moon over the water or an image in the mirror 水月鏡像. In the late 1960s, Lacan developed a theory of discourses as a method of questioning the imposed identity of the ego 我相. These questions would be: "Why am I who you say that I am?"or as Bernstein paraphrases, "What am I and for whom?" By questioning the subject's servility to the illusive Others, the Real is able to make its presence. On a deeper level, Lacan's extensive analysis of desire meant to free the ego from the fabric of Symbolic illusions 捨緣離相. In his approach to psychotherapy, Lacan rejects the attempt to unify the ego's psychic life 我執 in order to provide a temporary sense of coherence. He explains that such a unified self was developed during the infant's mirror stage, a process of identification with the mother/Other. This developmental stage is the origin of the split ego as well as the seat of neurosis 迷悟之源. For Lacan, the only way to unburden the ego 斷惑滅苦, the illusory image of one's self, is to undergo a series of articulated discourses through which one learns that the self is only a social construct and "a thin, weightless and empty self without substance " 照見五蘊皆空. To simply put: "The end of desire is the end of subjectivity". Only then, the mind is capable of reflecting a mirror like clarity 寂而恆照, 照而恆寂. The final point to be made here is that, either from a Buddhist perspective or psycho analysis, at heart of their work, depicts the core meaning of the Four Noble Truths 四聖 諦. The origin of desire 苦諦 as both Nargarjuna and Lacan explicated, has to do with one's surplus drive rather than the actual seeking. The narcissistic ego, according to them, is the seat of dukkha 心染故眾生染, 心淨 故眾生淨, the realm of suffering. As for the path that leads to the cessation of suffering 滅諦, Sartre, Lacan and Nagarjuna, each offers a way of being in the world of impermanence 無常. 16 One may wonder if there is a way to free oneself from the constraint of the Symbolic Other? To find the answer to this question, one needs to look no further than the countless literature in Eastern philosophy as it seems suggested by Lacan. Among various systems and practices concerning the way to a free mind 念念無滯 is the sage knowledge of Lao-Tzu (5th century BC) and Chuang-Tzu (369 BC), both are influential Taoist philosophers. They describe that a free man is unconcerned 空有雙泯 , who lives outside of culture but finds solace in nature. According to their philosophy, all lives are "Pu 樸", meaning "put together by nature". The literary meaning of Pu is "uncarved wood"; it refers to the original state of things 本相 prior to the process of societal indoctrination. Within the cryptic course of nature, the human self hangs in the peripheral like a speck of dust in an infinite universe. In a godless world, David Hume offers his consoling statement, "Nature herself is suffice. One may also think of Sartre's being-in-itself and Lacan's unsymbolizable Real, are part of the life's mystery, irrelevant to culture and the psychic state of the mind. Beyond language, ideas and man's search for meaning, all things are already in tune with a larger universe 曰月星辰, 山河大地 . Although the experience of nothingness is often associated with alienation, paradoxically, it also opens to a path of freedom. "One is free when does not get involved in fixation, attachment or clinging, nor resolved on one's self 不起執心", affirmed by Nagarjuna. A free mind is a state of non-abiding 非有非空. Through the unfolding of prajna, the intelligible knowing 妙覺, one can dissipate the unhappy consciousness into the evanescent 萬滯同盡 and transform the nihilistic nothingness 虛 無 to a free play of no-thing-ness. Through the unfolding of sunyata, the restless mind is transformed into a quiet heart. 山 堂靜夜坐無言, 寂寂寥寥本自然 (川禪師頌). February 2013 Foot notes: 1. Nagarjuna's work was translated into Chinese and had great influence on the Sanlun School 三論宗 (Three Treaties School), an early Mahayana Buddhist sect during the Sui 隋 and Tang 唐 Dynasty. Ji-Tsang 吉藏, an eminent priest scholar, was summoned by Emperor Sui (the first emperor to unite both the Southern and Northern Dynasties 南北朝), to propagate the teachings of Nagarjuna through which 17 Buddhism was flourished in China. The Middle Way is a methodology in Nagarjuna's system. It is a linguistic and dialectic strategy to abandon any absolute position 破相遣 執. The same method was employed in Sanlun School and later incorporated into the Zen practice (三論宗- 僧詮: 頓跡 幽林, 禪味相得). Its approach is by uttering paradoxical phrases in order for the teacher to help students to realize that the unsayable 以心傳心, 不立文字 cannot be attained through rational discourses. 2. 本文主要意旨是依據東西方三個不同的哲學系統,包括沙 特的存在主義、 勒康的心理 分析與龍樹論師的中觀哲學,作互相參照。並延伸他們西方的觀念,來詮釋無我,尤 其是關於依他起性 dependent origination 的論証。也許,這種嚐試 對三論學者以及心 理分析學派來說,可能有越界的問題。事實上,己有學者介紹龍樹的中論與後現代 語 言分解 Linguistic deconstruction 的關聯。 勒康的体系,龐大複雜,深受黑格爾、海德格、人類學以及 超現實主義影響。其主要 思想,包括彿洛依德理論及語言結構分析 structural linguistics。他的後現代「破相」 方法與中觀論近似,甚至可以和禪宗作連結。 References: 1. Jeffrey Hopkins, 1996, Meditation on Emptiness. 2. Jean-Paul Sartre, 2001, Being and Nothingness. 3. Jean-Paul Sartre, 1987, Existentialism and Human Emotions. 4. Jacques Lacan, 2006, Ecrits. Translated by Bruce Fink 5. Lorenzo Chiesa, 2007, Subjectivity and Otherness. 6. Bruce Fink, 1995, The Lacanian Subject -Between Language and Jouissance. 7. Jeanne Wolff Bernstein, 2012, Jacques Lacan from Text Book of Psychoanalysis. 8. Stephen Ross, 2002, A Very Brief Introduction to Lacan. 9. David Hume, 1975, Enquiries Concerning Human Understanding and Concerning 18 the Principles of Morals. 10. Sigmund Freud, 1989, Civilization and Its Discontents. 11. Nagarjuna- The Fundamentals of the Middle Way, 1998. Edited by George Cronk 12. Hsueh-Li Cheng, 1981, Nagarjuna, Kant and Wittgenstein. 13. 宗密: 禪源諸詮集都序 14. 黃懺華: 中國佛教史