Trade Marks(Week 2)

advertisement

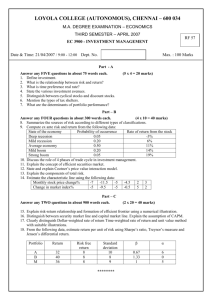

Intellectual Property Winter Session 2015 A trade mark is a sign used, or intended to be used, to distinguish goods or services dealt with or provided in the course of trade by a person from goods or services so dealt with or provided by any other person “sign ” includes the following or any combination of the following, namely, any letter, word, name, signature, numeral, device, brand, heading, label, ticket, aspect of packaging, shape, colour, sound or scent. “Use” is defined in s 7 of the TMA: • • • use of the trade mark upon, or in physical or other relation to, goods (s 7(4)) or services (s 7(5)) – includes use in invoices and advertisements (so long as goods or services are available to be ordered or traded) visual use and aural use (if trade mark is letter, word, name, number) (s 7(2)) Owner’s use and authorised use (s 7(3)) Note: The filing of a TM application creates a presumption of intention. The Registrar will not enquire as to whether a proposed mark is used or intended to be used but lack of intention may be a ground for opposition under s 59/s 62. Early Cases: Batt’s Case (1898 UK case) • “bona fide” intention to • use the mark Ducker’s Trade Mark (1928 UK case) • Imperial Group Limited v Philip Morris & Co Limited • “real resolve, intention and purpose” to use the mark • • “Nerit” was a ghost mark registered as a means of reserving “Merit” (which was not registrable) “Nerit” was only to be used to prevent others from using “Merit” (intention to use the mark but not in good faith because intent was to create a de facto monopoly) Over 1 million cigarettes sold under “Nerit” when use became necessary (but court still found no genuine intention to use the mark) Now s 62A prevents registration of marks not applied for in good faith To obtain registration of a “defensive trade mark” (see s 185 of the TMA): • • • • trade mark already registered (s 185(1)); trade mark used to such an extent, on some or all of the goods for which it was registered, that the use of the trade mark in relation to other goods or services would be likely to be taken as indicating a connection between those other goods or services and the registered owner (s 185(1)) registerable as to certain goods and services even if there is no intention by the owner to use the mark in relation thereto (s 185(2)) convertable to/from a distinctive mark (s 185(3), (4)) Definition of “distinguish” Shorter Oxford Dictionary 1 To divide or separate; to class, classify 2 To mark as different or distinct; to separate Roget’s Thesaurus difference, discrimination, severalise, separate • • • • The role of a trade mark is to establish a connection between the product and its source (i.e., be an indication of its origin). A consumer should be able to distinguish the product from other trader’s products. These are X goods, not Y goods or Z goods An example of a trade mark that would not be “capable of distinguishing” is the name “MILK” for the sale of milk. However, “JOHNSON FARM DAIRY MILK” may be capable of distinguishing Typically distinctive trade marks are those which are: • • • Invented words (such as KODAK) are usually distinctive (except when they become generic, like XEROX) Coined expressions (such as “This sick beat”) Concocted shapes (such as the millenium bugs) By necessary implication from s 41, the following trade marks are or can be “capable of distinguishing”: 41(3): trade mark is inherently adapted to distinguish 41(5): trade mark is to some extent inherently adapted to distinguish based on combination of: • use and intended use • extent inherently adapted • other circumstances 41(6): trade mark is not inherently adapted to distinguish but use before filing date does in fact distinguish • • • Inherent distinctiveness depends on the nature of the trade mark itself so must be determined in the appropriate context “Raising the Bar” amendments clarify the presumption of registrability (doubts resolved in applicant’s favour) Note 1 to s 41(6) states that trade marks consisting of the following signs are generally not inherently distinctive: kind, quality, quantity, intended purpose, value, geographical origin, or some other characteristic, of goods or services time of production of goods or of the rendering of services "The applicant's chance of success in this respect (ie. in distinguishing his goods by means of the mark, apart from the effects of registration) must, I think, largely depend upon whether other traders are likely, in the ordinary course of their businesses and without any improper motive, to desire to use the same mark, or some mark nearly resembling it, upon or in connection with their own goods. It is apparent from the history of trade marks in this country that both the Legislature and the Courts have always shown a natural disinclination to allow any person to obtain by registration under the Trade Marks Acts a monopoly in what others may legitimately desire to use.” Lord Parker in Registrar of Trade Marks v W & G Du Cros Ltd (1913) “[T]he question whether a marks is adapted to distinguish [is to] be tested by reference to the likelihood that other persons, trading in goods of the relevant kind and being actuated only by proper motives . . .will think of the word and want to use it in connexion with similar goods in any manner which would infringe a registered trade mark granted in respect of it”. Clark Equipment Co v Registrar of Trade Marks (1965) Early Case – Mark Foys (“Tub Happy”) Trade mark infringement case (1956) in which High Court stated the following in finding the trade mark inherently distinctive: • • • • Defendant’s use of the words "Tub Happy Cotton Fresh" in connection with advertising for "Exacto" brand cotton garments infringed the trade mark "Tub Happy" (obtained in respect of articles of clothing) Defendants were advertising the phrase "Tub Happy" for the purpose of indicating a connection between the goods which did not exist “Tub Happy” may have an “emotive tendency” but they did not “convey any meaning or idea sufficiently tangible to amount to a direct reference to the character or quality of the goods”. Words provided a “cloudy suggestion” they would wash well in a tub “but that is all” Letters • • • • One letter: not capable of distinguishing Two or more letters: capable if no descriptive significance (e.g., GT for car) Abbreviations: not capable of distinguishing if recognised abbreviations (e.g., OJ or BYO) Phonetic equivalents: if letters not capable then phonetic equivalent unlikely to be either (e.g., OJAY) Words No – words need to be used by traders to describe their goods: • Generic words – “Car” • Kind (includes size or type) – “Whopper” • Quality (laudatory words) – “Superior” • Intended Purpose – “Roach free” • Value – “Two for one” • Time of Production – “Vintage 1990” Words (cont) • Minor variations in spelling – “Kar” • Adjective form of words – “Minties” • • • Combination of two or more known words – “Vapo-Rub” Foreign words – if English word not capable, then foreign equivalent not capable – “Talla” Mr, Dr, My before word – no if following word not capable and for common surnames – “Mr Smith” or “Dr Nguyen” Sports Warehouse v Fry Consulting Sports Warehouse trading in California in 1994 in tennis apparel. Products sold in Australia since 1995 via website www.tennis-warehouse.com On 18 August 2005, Sports Warehouse filed an application to register the word mark TENNIS WAREHOUSE. Distinctiveness objection overcome after Sports Warehouse filed evidence of its use of the mark showing that the mark had acquired capacity to distinguish Application successfully opposed by Fry Consulting, an Australian wholesaler and retailer of tennis apparel and tennis gear through its website www.tenniswarehouse.com.au “In the context of online services, the public is likely to understand a domain name consisting of a trade mark…as a sign for the online services identified by the trade mark as available at the webpage to which it carries the Internet user” (Kenny J) Use of the domain name www.tennis-warehouse.com constituted use of the mark TENNIS WAREHOUSE with additions or alterations that did not substantially affect the identity of the mark Ocean Spray Cranberries v Registrar of TM • • “CRANBERRY CLASSIC” to no extent inherently adapted to distinguish for fruit juices as it conveyed “the notion of excellence” and meant “quality cranberry” Court agreed that the power of advertising may be able to turn almost anything into a trade mark but here the mark was not capable of distinguishing (even though it may have acquired a distinctive character) Modena Trading v Cantarella Bros • • • Italian words “Oro” (gold) and “Cinque Stelle” (five star) used in relation to coffee products Marks rejected for being merely descriptive. High Court determines that marks are distinctive and overturns decision below New test for determining whether a trade mark is inherently adapted to distinguish the claimed goods or services: What is the 'ordinary signification' of the words proposed as trade marks, to any person in Australia concerned with the relevant goods claimed by the trade mark? (here not commonly used Will other traders legitimately need to use the word in respect of their own goods? Howard v Auto-Cultivators v Webb Industries Inventive word “rohoe” as a contraction of the English words “rotary” and “hoe” not registrable given the ordinary signification recognisable to other traders made it a word that other traders would have legitimate interests to use Geographical names No capability to distinguish where obvious or potential connection with goods or services Blount Inc v Registrar of Trade Marks Use of upper-case letters, and the oval device surrounding the word "Oregon” not sufficient to make descriptive word “Oregon” distinctive for chainsaws Clark Equipment Co v Registrar of Trade Marks Trade mark for “Michigan” for earth-moving equipment "plainly not inherently, ie in its own nature, adapted to distinguish“ Geographical names “COLORADO” for backpacks? (Colorado Group Limited v. Strandbags Group Pty Ltd) “PHOENIX” for toiletries? (Re Application by Unilever Plc) Mastronardi Produce v Registrar of Trade Marks • ZIMA an invented word but only used in relation to one variety of golden grape tomatoes • Registrar refuses application because describes goods • Court posed test as: (1) How would ZIMA be understood as at 25 July 2011by ordinary Australians seeing it for the first time used in respect of tomatoes; (no meaning as made up word) (2) How likely is it that other persons, trading in tomatoes and being actuated only by proper motives, will think of the word ZIMA and want to use it in connexion with tomatoes in any manner which would infringe a registered trade mark granted in respect of it? (had other options because did not need to use the word ZIMA to describe their products) Composite Trade Marks • Trade marks comprising any combination of words, devices, shapes, sounds, scents and/or colour elements “It is established that a combination mark may be capable of distinguishing by the overall impression it creates, even if the individual elements in isolation lack any such capacity, because, for example, they are commonplace in a trade, or, by parity of reasoning, merely or highly descriptive.” Fry Consulting Pty Ltd v Sports Warehouse Inc Crazy Ron’s Communications v Mobileworld Communications Relatively large fantasy cartoon character holding a mobile telephone astride a stylised globe Words not especially prominent and subsidiary to fantasy character which occupied dominant position in overall image Crazy Ron did not infringe Crazy John because mark is device Image overwhelms words Colours • • • “Most objects have to be some colour. So merely applying a colour to a product will not act as an identifier for that product. In deciding whether colour functions as a trade mark it is necessary to determine whether the trader has used the colour in a way that informs the public that the product emanates from a particular source.” (Woolworths v BP) (Colour green) Must show that you have used the colour as a trade mark and that the public have come to identify that colour with your particular goods or services Cadbury's were unable to register the general colour purple but were successful in registering a specific shade of purple as a trade mark, when used on the packaging for block chocolate and boxed chocolate indicator of origin whether it indicates the trade origin using a sign to indicate a connection in the course of trade between the goods and the person who applies the mark • Contain certain signs – s39 (s18, r4.15) (“Patent”, coat of arms, official flag, official seal etc) • Can’t be graphically represented – s40 • Not distinguish goods/services – s41 (see above) • Scandalous or contrary to law – s42 (red cross, ANZAC, Olympic logo, etc) Trade Mark : 1025788 Word: ASSHOLE Image: Lodgement Date: 19-OCT-2004 Registered From: 19-OCT-2004 Date of Acceptance: 07-FEB-2005 Acceptance Advertised: 24-FEB-2005 Registration Advertised: 08-SEP-2005 Entered on Register: 22-AUG-2005 Class/es: 16 Status: Removed - Not Renewed Kind: n/a Type of Mark: Word Goods & Services Class: 16 Greeting cards, humorous cards, birthday cards, stickers, prints, books, card paper, paper Because of some connotation ◦ that the trade mark has ◦ that the sign contained in trade mark has ◦ in other words, this ground is available only where the misleading connotation is inherent in the mark (rather than based on the context of its use) For example: ◦ “Polo Magazine” for publications not about polo (deceiving) ◦ “Bali” bras not made in Bali (unlikely to deceive) Confusion did not depend upon some connotation in the registered mark, but because TGI Friday was using a similar name – not covered by s 43 • • DIANA’S LEGACY IN ROSES together with a device comprising doves, a wreath of flowers and a stylised letter “D” Real tangible danger that, by virtue of the connotation of the late Princess in the impugned mark, consumers in Australia would be deceived or confused by incorrectly believing that the mark was indicative of some endorsement or approval by the Fund or the Estate of the late Princess registered mark for services ◦ similar services ◦ closely related goods registered mark for goods ◦ similar goods ◦ closely related services ◦ unless honest concurrent use – s44(3) ◦ unless prior use – s 44(4) Test: Compared side by side, their similarities and differences noted and the importance of these assessed having regard to the essential features of the registered mark and the total impression of resemblance or dissimilarity that emerges from the comparison Deceptively similar if so nearly resembles that other trade mark that it is likely to deceive or cause confusion (s10) Crazy Ron’s v Mobileworld • impression based on recollection of the applicant’s mark that persons of ordinary intelligence would have compared to impression such persons would get from respondent’s mark • human frailty so imperfect nature of recollection • aural similarity may be important • tangible risk of deception – enough if ordinary person entertains a reasonable doubt • • • • Effem registered trade marks SCHMACKOS and DOGS GO WACKO FOR SCHMACKOS Wandella apply for WHACKOS in same class WHACKO not deceptively similar SCHMACKOS because SCHMACKOS more complex sound and more visually complex but WHACKO deceptively similar to DOGS GO WACKO FOR SCHMACKOS because total phrase derives whole of its force from the word WACKO. WACKO was powerful component of Effem's mark which would be retained in consumer’s memory and recalled when Wandella's mark seen S 14: (1) For the purposes of this Act, goods are similar to other goods: (a) if they are the same as the other goods; or (b) if they are of the same description as that of the other goods. (2) For the purposes of this Act, services are similar to other services: (a) if they are the same as the other services; or (b) if they are of the same description as that of the other services. Southern Cross Refrigerating v Toowoomba Foundry Consider all legitimate uses which may reasonably make of the mark within ambit of the applicant’s registration • • • Gas absorption refrigerators and electric refrigerators and parts thereof Well-drilling and boring machinery hand or power, milking machines, engines, windmills Similar goods involves consideration of ◦ nature of goods ◦ uses to which they are put ◦ whether they are commonly sold together to the same class or classes of customers Registrar of Trade Marks v Woolworths Ltd Range of relationships between goods and services which may be "closely related” In most cases relationships defined by function of service with respect to goods. Services which provide for installation, operation, maintenance or repair of goods are likely to be treated as closely related to the goods Caterpillar Loader Hire v Caterpillar Tractor Co Confusion is more likely to arise where services protected by service marks necessarily involve the use or sale of goods or where services (eg consultancy services) involve goods (1) the honesty of the concurrent use; (2) the extent of the use in terms of time, geographic area and volume of sales; (3) the degree of confusion likely to ensue between the marks in question; (4) whether any instances of confusion have been proved; and (5) the relevant inconvenience that would ensue to the parties if registration were to be permitted. • • • • • • Mary McCormick registered MCCORMICK for instant batter associated with distinctive fish and chips sold by Mr and Mrs McCormick from roadside caravan Aware at time name chosen that certain mixed herbs, paprika, pepper and basil products were sold under MCCORMICK brand May be honest even though aware Entitled to be registered in Queensland but opposed because of section 60 Mary McCormick later changed to “Mary Macks” • • Mark is substantially identical or deceptively similar to previously registered mark BUT applicant used before the previously registered mark was registered Applicant’s use Other Owner’s registration Applicant’s application