Alan Craig-Why change the law

Draft Paper: Not for publication

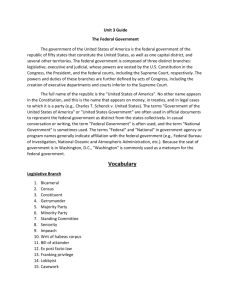

Why change the law? UK-Israel relations in the shadow of the

Universal Jurisdiction.

Author Details: Dr Alan Craig, Pears Lecturer in Israel and

Middle East politics, University of Leeds. Contact: a.craig@leeds.ac.uk

Abstract

: In the light of the 2011 changes in the UK universal jurisdiction law restricting the right of the UK citizen to prosecute war crimes, this article examines the tension between the apparently competing principles of ending impunity for war crimes on the one hand and sovereignty and the demands of stable international relations on the other. The argument is advanced that the politics of the UK Israel bi-lateral relationship generated a common interest between the two states in increased UK government control of the prosecution process. The article examines the UK universal jurisdiction regime both before and after the 2011 reforms and concludes that, despite this apparent coincidence of interest, government control remains incomplete, with the possible arrest of visiting Israeli elites constituting a continuing unresolved tension between the processes of UK human rights law and the demands of international relations.

Introduction

The universal jurisdiction allows states to reach out beyond their borders to prosecute non-citizens. This is the criminal jurisdiction of the state,in its own courts, over foreigners in respect of alleged criminal acts committed outside the country.

1 In political terms, it is an assumption of state power over non-citizens for their wrongdoing beyond state borders. As such, the very concept of the universal jurisdiction is a challenge to state sovereignty. The exact terms of the jurisdiction and the degree to which states limit its extent vary from country to country and even then from offence to offence 2 .

The universal jurisdiction sits uneasily alongside domestic jurisdictions because state legal systems are overwhelmingly territorially located within state boundaries. The universal jurisdiction is founded on a different presumption- that there are some crimes that so offend humanity they should be capable of being tried anywhere, irrespective of the nationality of the perpetrator. Giving effect to the idea of the universal jurisdiction depends on states legislating to

1

amend their domestic law to criminalise acts of foreigners committed abroad- a bottom up process among a society of states that promotes a liberal discourse of the universality of human rights and of an end to impunity for their violation(Roth, 2001). The jurisdiction seeks to plug the gaps left by the failure of international organisations to punish human rights abuses in war and provides a route to justice for victims let down by their own domestic legal institutions.

For supporters of the universal jurisdiction, the bigger picture is one of relations between states strengthening through the structure of international law and disrupted bi-lateral relations are a small price to pay for an international order that guarantees justice for the victims of war crimes.

3 But for those, such as Jack

Goldsmith and Eric Posner, with a more realist view of international relations, courts are there to be deployed in the pursuit of state interest and, more frequently, constrained where their involvement runs counter to policy. For

Goldsmith and Posner, it is not just that liberal democracies pursue self-interest ahead of cosmopolitan concerns for the stranger, it is their democratic duty to do so(Goldsmith & Posner, 2005). This is an instrumental view of international law that is driven by the requirements of state.

The UK experience has been shaped by a marked lack of state enthusiasm for universal jurisdiction prosecutions. Instead, the political space has been filled by

NGOs. Following the 2001 World Conference against Racism pro-Palestinian

NGOs adopted a policy of legal initiatives against, and outside, the Israeli state.

The UK courts became a legal battlefield where NGOs sympathetic to the

Palestinian cause attempted to mount universal jurisdiction prosecutions against visiting Israeli elites. In 2011, following several high profile attempts to have visiting Israelis arrested, and amid deteriorating relations with Israel, the UK changed its universal jurisdiction law in an effort to block politically motivated prosecutions. This article uses the 2011 reform as a case study of how national interest in international affairs impacts on the international reach of domestic human rights law and informs the politics of the international jurisdiction.

While it is accepted that the universal jurisdiction is far more than the sum of

Israeli and UK national interest and that other states have concerns about the jurisdiction, the study is illustrative of the tensions and changes within the jurisdiction generally and the impact of the demands of international relations on domestic human rights law.

2

This article will examine the role of states and NGOs in the politics of the universal jurisdiction and explore the tension between the goal of ending impunity for war crimes and the reluctance of government to incur international relations costs. The article will then examine the UK universal jurisdiction regime before and after the enactment of the Police Reform and Social

Responsibility Act in 2011 before concluding with an assessment of the extent to which the state has wrestled control of the jurisdiction from NGOs.

Universal jurisdiction cases and the national interest

This tension between the collective interest of the state and the interest of the non-national individual whose human rights have been violated is, of course, subject to the strategic deployment of international power by those states whose political and military elites face the threat of prosecution. In other words there is an international relations cost to bringing universal jurisdiction prosecutions.

This provides the basis for the theoretical model advanced by Maximo Langer, where the decision to prosecute is informed by a cost benefit analysis that weighs the benefits of domestic support for the prosecution of foreign human rights abuse against the international relations costs so that,

[T]he political branches of the prosecuting states must be willing to pay the international relations costs that the defendant’s state of nationality would impose if a prosecution and trial take place. As these costs can be substantial, universal-jurisdiction-prosecuting states have strong incentives to concentrate on defendants who impose low international relations costs because it is only in these cases that the political benefits of universal jurisdiction prosecutions and trials tend to outweigh the costs(Langer, 2011, p. 2).

Langer’s analysis, while perhaps underplaying the promotion of human rights as a foreign policy value in itself and overplaying rationality in the affairs of states, supports a persuasive argument that in practice universal jurisdiction prosecutions are conducted against low-cost offenders who lack powerful state support. From the perspective of the prosecuted, this perceived partiality in invoking the jurisdiction leads less powerful states to see such prosecutions as an unjustifiable threat to their sovereignty.

4 Currently, the legal committee of the UN General Assembly (Sixth Committee) is reviewing the scope of the universal jurisdiction. It is divided over the issue of restricting the jurisdiction, with the African Group and Non-Aligned Movement calling for a limitation of a power to prosecute that is being selectively employed against either their members(General Assembly). They have a point. Langer’s research shows that,

3

discounting cases concerning former Nazis and citizens of the former

Yugoslavia, most successful universal jurisdiction cases involve African nationals- leading to repeated calls for change from the African Union and for the sovereignty of African states to be respected.

But states, particularly democracies, do not have absolute control over access to their courts and cannot always rely on Judges to respect the foreign policy preferences of the government of the day. This is important since imperfect state control of the jurisdiction has the potential to create opportunities for interested parties to circumvent the rational choices of state foreign policy advisers. Unless, the state can retain control of the prosecution process it may find itself saddled with the inconvenient prosecution of those it would prefer to see dealt with elsewhere. This is well illustrated by the recent history of the abortive prosecution of US elites in the courts of its Western democratic allies, particularly Germany, France and Spain. Katherine Gallagher’s study of the prosecutions in each of the three countries reveals a process of NGOs filing complaints against US officials, state prosecutors resisting prosecution and ultimately changes in state domestic law to curb the jurisdiction(Gallagher,

2009). It follows that there is an important distinction to be made in the analysis of universal jurisdiction prosecutions between those prosecutions brought by the state and those brought by private individuals, or more likely NGOs, with the

New York based Centre for Constitutional Rights, European Centre for

Constitutional and Human Rights, the international Federation for Human

Rights active in promoting the prosecution of US officials. Once these prosecutions, which often do not get past pre-trail legal proceedings, are taken into account,the profile of the potential defendant shifts to include nationals of those states that most offend international NGOs.

The private/public or NGO/state distinction is not the only useful framework.

Luc Reydams, distinguishes ‘virtual’ cases from the ‘hard’ cases. Hard cases are prosecutions that go to trial while virtual cases are little more than an engagement with pre-trial legal procedures where a trial is never a realistic prospect. This distinction is helpful because the importance of the virtual cases is a measure of the political rather than legal power. Orchestrated by NGOs, and producing little more than headlines and diplomatic headlines,

[t]he cases mentioned above [the virtual cases] showed that universal jurisdiction was anything but universal in practice. As an almost exclusively European affair they represented a curious mixture of mission

4

civilisatrice and resistance against United States hegemony and Israeli exceptionalism (Reydams, 2003, pp. 349-350).

They are virtual because they do not get past the pre-trail processes to a final determination of guilt. In the judgment of the home state, such cases involve unacceptable international relations costs (otherwise the state would be prosecuting) and state institutions will take action to block attempted prosecutions instigated by non-state actors. The cases burn brightly in the public consciousness before fizzling out, but not before the legal processhas had a political significance beyond the particular circumstances of the individual defendants. Alleged perpetrators are invariably representatives of state political and military elites, whose acts reflect the policies of their governments. Tying a state to allegations of crimes so serious that they offend the conscience of humanity through the simple expedient of issuing an arrest warrant empowers not only the victim but also the raft of sympathetic NGOs orchestrating the legal proceedings. The very failure of the case is framed within a discourse of human rights as evidence of legal exceptionalism, impunity, and collusion on the part of the domestic state that has failed to support the prosecution through shabby self-interest. This narrative presents a normative challenge to both the defendant’s state and the state in which the failed prosecution has taken place.

In the Israeli case, there has been a coordinated strategic use of the jurisdiction by pro-Palestinian NGOs to bring criminal proceedings on behalf of

Palestinians pursuing allegations of war crimes against Israeli political and military elites visiting the UK. While viewed by the proponents as a challenge to Israeli exceptionalism by Palestinians seeking justice outside the Israeli legal system(Machover, 2012), these attempted prosecutions are recognised by

Jerusalem as having a political significance that far exceeds their legal import.

The legal proceedings are conceptualised in Israel in security terms as ‘lawfare’- a term coined in the US Charles J. Dunlap Jr. to describe the use of law as an unconventional weapon of war.This frames the legal process as an offensive strategic weapon rather than a route to justice for victims of crime. The analysis gains purchase when seen as an aspect of a wider pro-Palestinian strategy of delegitimation of Israel through the legal and ethical condemnation of Israeli military operations.

5

This further framework of analysis links human rights law to international legitimacy. International legitimacy is the normative measure of a state’s entitlement to the benefits of membership of the international community-

5

particularly the sovereignty and the right to self-defence(Clark, 2005).

Declining legitimacy can ultimately lead to rogue status leaving the state vulnerable to external penetration. It is a matter of state security beyond the personal security of travelling state elites but the two are inextricably linked.

Legal and ethical judgments play a big part in our assessment of international legitimacy. From this perspective delegitimation through the legal and ethical impact (legitimacy costs) of the threat of prosecution for war crimes of state elites in the capitals of Europe impacts directly on Israeli security- a connection revealed by the involvement of the Israeli security cabinet in directing the allocation of recourses to addressing the problem(Rosenzweig & Shany, 2009).

This gives rise to another strategic cost-benefit calculation, which mirrors that of the prosecuting state. States whose nationals are facing prosecution need to decide how far they are prepared to go in disrupting bi-national relations to halt the risk of prosecution. In so doing, the legitimacy costs of enduring the prosecution process are weighed against the cost of taking action against the prosecution state.

The UK law

UK international jurisdiction offences arise, in the main, from domestic legislation passed to meet the obligations entered into through participation in specific international conventions concerning torture, hostage taking and certain other terrorist offences.

6 Subject to varying requirements of residence within the jurisdiction, the law allows prosecution in the UK of non-citizens for offences committed abroad, with protection for heads of state who enjoy immunity from prosecution under section 14(1) of the State Immunity Act of 1978. In relation to the high profile allegations of war crimes, the jurisdiction arises from a commitment to prosecute grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions.The obligation on states to prosecute these grave breaches is located in Article 146

Geneva IV 1948, which requires state parties to the convention to amend their penal code to allow prosecution of perpetrators of war crimes wherever they have been committed and, to ‘bring such persons, regardless of their nationality, before its own courts.’

In the UK, the Geneva Convention call for domestic legal action resulted in the Geneva Conventions Act (1957), as amended in 1995, which provides that,

1.-(1) Any person, whatever his nationality, who, whether in or outside the United Kingdom , commits, or aids, abets or procures the commission by any other person of a grave breach of any of the [1949 Geneva]

6

conventions or the first [Additional] protocol shall be guilty of an offence

[emphasis added].

There is an important legal restraint written into the UK law. Prosecutions under the Act cannot be started without the consent of the Attorney General, whose role is to consult with and advise the Government on legal issues. The key question is how does the Attorney General decide when and when not to consent? This is a two part test. Firstly, there must be a likelihood of success and, secondly, a prosecution must be in the public interest. The likelihood of success is a matter of matching evidence to law, but whether a prosecution is in the public interest is inescapably a political judgment. On the face of it this is a matter for the Attorney General alone, but this ownership of the decision making process is less obvious when the Attorney General ‘consults’ ministers.The procedure, commonly referred to as the ‘Protocol Test’, is a matter of public record set out in The Protocol Between the Attorney General and the Prosecution Departments. While stressing that the decision is the

Attorney General’s, the suggestion that the decision is free of government influence is undermined by the express provision in the Protocol clearly stating that the Attorney General may consult with ministers for their views on whether a prosecution is in the public interest.

7

Public interest is a wide concept that clearly includes national security, which opens the way for matters such as bi-lateral intelligence sharing to be balanced against the public interest in maintaining the rule of law. These issues were challenged in court in 2008 whenThe Corner House, a UK based NGO with an international anti-corruption/human rights agenda, took the government to court seeking judicial review of thedecision not to prosecute British Aerospace over well substantiated allegations of bribery when competing for Saudi arms contracts ("R (On The Application of Corner House Research and Others) V

Director of The Serious Fraud Office," 2008). While recognising a strong public interest in the rule of law and in meeting international commitments to combat corruption,the UK’s highest court, refused to set aside the Attorney General’s assessment that a prosecution was not in the public interest. The Attorney

General had been quick to deny an economic motive of protecting a lucrative arms export industry. Rather, the evidence was that the Attorney General had consulted ministers and that the Prime Minister and the Foreign and Defence

Secretaries had, ‘expressed the clear view that continuation of the investigation would cause serious damage to UK/Saudi security, intelligence and diplomatic

7

co-operation, which is likely to have seriously negative consequences for the

United Kingdom public interest in terms of both national security and our highest priority foreign policy objectives in the Middle East’ and that the heads of the security and intelligence agencies and the UK ambassador to Saudi

Arabia had shared the assessment.The court found that there was nothing inappropriate in accepting the views of ministers and putting national security ahead of the rule of law when deciding what was in the national interest. As a consequence a strong but politically inconvenient case of serious illegality was dropped.

While this was not a universal jurisdiction case the same principles apply to explain the mechanisms of government control of the jurisdiction. In a cost benefit analysis the international relations costs of allowing the UK law to take its course were just too high. Of course, these costs will have included the damage to the UK’s very substantial arms export trade with the Saudis- an aspect of the relationship that was downplayed by the government when it came to defending its position in court. Although the judicial review case reached court, the prosecution did not and falls into the virtual category. The outcome, whether or not seen as appeasement of the Saudis or protection of a valuable export market, was one of the UK state beating off a challenge to its political control of its prosecution process.But the issue of Saudi members of the royal family taking bribes had become widely discussed with obvious legitimacy cost to the Saudi state, demonstrating the political impact of the virtual case.

In fact, there have been few hard cases in the UK. Aside from the successful

1999 prosecution of naturalised UK citizen Anthony Sawoniuk for the murder of Jews in Belorussia, the only other successful UK universal jurisdiction case involved FaryadiZardad (BBC News Online, 1 April 1999). Zardad had been exposed in 2000 by BBC correspondent John Simpson as an Afghan war criminal living in the UK and running a pizza restaurant in South London.

Between 1992 and 1996 Zardad had been the brutal operator of a checkpoint controlling the route between Kabul and Islamabad. Here was an allegation that was not going to undermine delicate bi-lateral relations. The Afghan Taleban government were only too happy to see Zardad punished, but even so, the UK authorities were not enthusiastic about a prosecution and only took action after the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan (RAWA) had mounted an international campaign. The outcome after two trials was conviction in 2005 and a sentence of 20 years imprisonment (BBC News

8

Online, 18 July 2005). There had been no legitimacy cost to Afghanistan and no effort to influence a UK cost benefit analysis by imposing international relations costs in the event of actual prosecution.

However, there are limits to government control of the prosecution process. The

UK legal system contains the ancient constitutional safeguard of the right of private prosecution.

8 This is the right of a private individual to bring a criminal prosecutionbefore a court in the event of the state refusing to prosecute offenders. It can readily be seen that the procedure operates to empower the citizen and the judiciary to act as a check on the arbitrary exercise by the government of its power to prosecute. But this constitutional right is effectively denied in the case of war crimes through the requirement that any prosecution, whether private or state, can only proceed with the consent of the Attorney

General. But before 2011 there was a serious gap in the state control of the private prosecution of war crimes- no consent was needed for an application to a court for an arrest warrant for the purpose of detaining a suspect for investigation.

9 This is a warrant issued by a judge designed to compel that attendance of the suspect at court. The question was not whether the court could be relied upon to act sensibly since the law set the bar very low. A warrant could be issued if the application simply 10 demonstrated a prima facie case- the availability of evidence sufficient, if correct, to prove the offence. This meant that arrest warrants could be issued by a court without examining the evidence in detail and in circumstances where the government may not even be aware of the court application let alone consented to a prosecution. There was simply no requirement to involve the government at this early procedural stage. The emotive step of arrest could take place without recourse to the government and, indeed, without no real expectation that the government would ever consent to a prosecution.

It was this procedure that gave rise to a rash of applications to the UK courts for arrest warrants between 2002 and 2011. Consistent with Gallagher’s research, they were instigated by concerned NGOs and to apply Langer’s typology, these were virtual cases that employed legal processes without reaching trial. They were almost without exception targeted at Israelis- the most famous of which concerned Doran Almog.

In 2005 expatriate Israeli citizen and UK solicitor Daniel Machover, acting in conjunction with the Gaza based Palestinian Centre for Human Rights on behalf of residents of Gaza to obtain a warrant for the arrest of Major General Doron

9

Almog (retired). On 9 September 2005 at Bow Street Magistrates Court District

Judge Timothy Workman issue a warrant for Almog’s arrest for suspected war crimes on the grounds that there was prima facie evidence of war crimes and that Almog was about to visit the UK to speak at a charity event.

11 The warrant was to enable a private prosecution and the Crown Prosecution service was not a party to the proceedings. The allegations concerned Almog’s command role in the 2002 assassination of Hamas bomb maker Salah Shehadeh, demolition of 59 houses in Rafah on 10 January 2002 and two other killings. The outcome is well known. While the police waited at the Heathrow immigration gate, the Israeli military attaché spoke to Almog by mobile phone from the M4 motorway and instructed him to stay on the El Al plane until it returned to Israel. The police stayed where they were and Almog returned to Israel. There had been a convenient leaking of information by the police to the event organisers in

Solihull, who had in turn contacted the embassy (Hickamn& Rose Press

Release, 11 September 2005).

Machover is not the only UK lawyer promoting Universal Jurisdiction cases in the UK. UK human rights lawyer Imran Khan had previously caused Sharon’s

Defence Minister ShaulMofaz to leave London in a hurry in 2002 by presenting a legal dossier to the Crown Prosecution Service alleging war crimes.The Israeli response to these legal manoeuvers was to warn its military and political elites against foreign travel where there is a risk of arrest. On Military advocate

General Mandelblit’s advice Brigadier-General Aviv Kochavi cancelled his place on a security course in London. Former IDF Chief of Staff Moshe Ya’alon was reported to have cancelled a trip to England on hearing that a spokesperson for the Israeli legal NGO YeshG’vul spoksman had announced that Ya’alon was among eight Israeli’s subject to war crimes files lodged with the police in

Metropolitan Police (Glick, 2005).

This cat and mouse game came to a head after a warrant for the arrest of former

Deputy Prime Minister Tzipi Livni in December 2009 and then withdrawn when it was found that she was not actually in the UK at all (Black, 2009). By now changing the UK law had by then become a top priority for Israel in its bilateral relations with the UK. As Israeli Prime Minister, Binyamin Netanyahu put it in December 2009,

We will not accept a situation in which Ehud Olmert, Ehud Barak and

TzipiLivni will be summoned to the defendants' chair....We will not agree to have Israel Defence Force soldiers, who defended the citizens of Israel

10

bravely and ethically against a cruel and criminal enemy, be recognised as war criminals. We completely reject this absurdity taking place in

Britain (BBC News Online, 15 December 2009).

The Labour government promised reform; releasing a statement after the Livni saga, Foreign Secretary David Miliband said, 'Israel is a strategic partner and a close friend of the UK. We are determined to protect and develop these ties.

Israeli leaders – like leaders from other countries - must be able to visit and have a proper dialogue with the British Government’ (Foreign and

Commonwealth Office News, 15 December 2009). This freedom of movement was to be achieved by removing from the UK citizen the right to bring a private prosecution for universal jurisdiction cases other than those committed by UK citizens or that had taken place in the UK. In fact, the Labour government had only limited support within its own party for such a move and made no real effort to change the law before suffering defeat in the May 2010 general election.

Changing the UK law

Changing the law had been a manifesto commitment of the Conservatives. But not their Liberal Democrat coalition partners, for whom a commitment to human rights was central to their political philosophy; nor were the Liberal

Democrats known for their support for Israel. Nevertheless, reform of the UK’s universal jurisdiction law was included in the Queen’s Speech on 25 May 2010.

The draft legislation in the shape of the Police Reform and Social Responsibility

Bill contained a new requirement whereby an application for an arrest warrant for war crimes could only proceed with the consent of the Director of Public

Prosecutions (DPP). Meanwhile in November 2010, before the Bill had been debated in Parliament, the issue again soured bi-lateral relations when Israeli

Intelligence and Atomic Energy Minister Dan Meridor cancelled a visit to the

UK following warnings of the threat of arrest over his role in the interception of the Turkish flotilla to Gaza in May of that year. Already, the previous month

Tel Aviv had signalled the degree of its concern when the security cabinet directed the creation of a dedicated department within the Israeli Ministry of

Justice to combat legal cases abroad and to regularly update the security cabinet on developments (Rosenzweig & Shany, 2009). The fact that this was designated as a security issue spoke to its importance.

The strength of Israeli diplomatic pressure was revealed on 3 November during the first official trip to Israel by the new Foreign Minister William Hague.

11

Hague was ambushed on his first day in the country when the Israeli government announced the suspension of the annual Strategic Dialogue with

London in protest against the threat of UK arrest warrants. Contextualising the decision that the strategic dialogue would not go ahead, Israel Foreign Ministry spokesman Yigal Palmor commented that, ‘The visit by Foreign Minister Hague is an important phase in the ongoing exchange between the countries and the question of Israeli officials being unable to travel to Britain will be on the top of the agenda as far as we are concerned’ ( Haaretz News , 3 November 2010). The strategic dialogue is the visible security and intelligence discussion, with the much more important security and intelligence cooperation taking place behind the scenes. Cooperation is particularly close in matters of Islamic terrorism,

Iranian proliferation and cyber security. The cancellation of the visible level of communication gives weight to the widely held belief that Israel was threatening a withdrawal from intelligence sharing unless there was rapid progress on curbing the issue of arrest warrants.

The Israeli pressure was interpreted in the UK as an unwelcome effort to influence the government’s timetable (Harriet Sherwood, 2011). Nevertheless, there was a flurry of UK diplomatic activity designed to reassure the Israelis with Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg declaring a new- found enthusiasm for the reform and a willingness to combat those within his own party who saw the change as an abandoning of the party’s core commitment to international human rights law ( JC News Online , 11 November 2010). There were still powerful voices both within and outside the coalition against the reform that framed the

Bill as an attack on human rights protection and sought to restrict any change to an obligation that went no further than a duty to inform the prosecuting authorities of any application for an arrest warrant.

12 Change duly came in

September 2011 with the passing of the Police Reform and Social

Responsibility Act, which retained the right to bring a private prosecution but took from the UK citizen the independent right to apply for an arrest warrant.

Power was to be concentrated in the hands of the DPP by making a small but very significant change to the law. From now on no member of the public would be able to obtain an arrest warrant in war crime cases without the prior consent of the DPP.

13 The change was designed to put an end to the virtual cases by putting the DPP in control.

14

The Government web site explained the need for change in terms consistent with a lawfare analysis: ‘The Government's aim in introducing this change is to

12

prevent the courts being used for political purposes’.There was no attempt during the Parliamentary debates to frame this as anything other than putting a stop to arrest warrants for Israeli visitors. Analysis of the new system throws up two issues: Have those who ‘used the courts for political purposes’ been excluded from the prosecution processes and to what extent will the DPP consent to the issue of a warrant be influenced by political considerations?

Since an arrest warrant can only be applied for with the consent of the DPP, and a prosecution can only go ahead with the consent of the Attorney General, the activists would appear to have been disempowered. The strategy of the CPS has been to reassure all concerned that the CPS will respond to demands for investigations and arrest. To this end there has been a policy of regular meetings between the CPS and activist groups. As DPP Kier Starmer explained to the

Parliamentary Committee during its consideration of the legislation, that the

War Crimes Community Involvement Panel is designed to get the police and the

CPs involved at an early stage so that it would be the police rather than NGOs acting if an arrest warrant were required (House of Commons, 2011, p. 123). It seems fair to assume that this open channel of communication of evidence of alleged Israeli war crimes gives a role to activist groups, but not an independent role.

15 The extent of their influence remains to be researched.

The second question concerns the extent to which the DPP’s consent to the issue of a warrant will be a political decision.The logic of the change in the law is to give the state greater control over the issue of arrest warrants in private prosecutions. This would not be achieved if the DPP were to apply the same test as the magistrate. It follows that the DPP would have to apply a more rigorous test for the government to achieve its intended outcome. This is an entirely new power for the DPP and during the legislative process MPs were anxious to know how the Director would exercise his new power. Sure enough, Starmer made it clear in his evidence before the Public Bill Committee that he would apply a different test from that used by the court. This would be the test required of the Attorney General when deciding whether or not to prosecute (the

Protocol Test). It will be recalled that the Protocol Test is in two parts: sufficient evidence to provide a realistic prospect of conviction and for prosecution to be in the public interest. It is immediately apparent that this is a higher test than that the prima facia case required by the magistrate.

It is not immediately clear why the DPP should take this approach other than to abort private prosecutions at the earliest possible stage.Technically, there is no

13

reason why the DPP should not simply adopt the prima facie test that the court had been applying- that there is evidence of an offence. After all, this is a consideration of whether to arrest- not whether or to prosecute, which is a decision that may come several months later. Starmer’s justification to the committee was to point out that this was a power to be exercised in relation only to private prosecutions. His point was that in public cases the space between arrest and prosecution is used to test the evidence in interview with the accused.

Since in private cases the accused is not going to be interviewed the process of arrest and charge is collapsed and it is right to use the higher test at the earlier stage of deciding whether to arrest (House of Commons, 2011, pp. 127-129).

While this is a practical approach that can be used to kill off private cases at the earliest possible stage, there is nothing in the legislation that requires such an early application of the Protocol Test and it is not immediately clear that other

DPPs will exercise their power in the same way or that this particular approach would be upheld by the courts.The key question is the extent to which political considerations will be taken into account in assessing whether the issuing of a warrant is in the public interest. Indeed, this was the focus of the human rights attack on the legislation as it made its way through the legislative process.

Writing in the letters section of The Guardian , a group of over seventy influential legislators and public figures argued that, ‘giving a power of veto to the DPP would risk: political interference by ministers in the arrest of war crimes suspects’ and that ‘the change in the law would risk creating a culture of impunity’ (

The Guardian , 13 December 2010).

So who will the DPP consult? The answer seems to be the Attorney General who will consult ministers. During the Parliamentary committee stage of the new Bill, 16 Starmer was pressed on how the new system would work in practice.

Appearing before the House of Commons Public Bill Committee, Starmer was keen to establish that Parliament had given the decision to him, not the Attorney

General, and explained how he would go about it,

There may be a need to go for a warrant for arrest. In those circumstances, we would propose applying the code test, so we would broadly apply the principles of, “Is there sufficient evidence to provide a realistic prospect of conviction?” and, “Is it in the public interest?” If those tests are satisfied, I give consent to the warrant(House of

Commons, 2011, column n. 124).

The starting point was that evidence of serious crimes would be a powerful argument for consent to an arrest warrant. But the AG was still going to be the

14

one to later decide on whether to take it to the next stage- whether or not to prosecute. So it made sense for the DPP to consult the AG at the arrest stage.

Since the AG consults with ministers, it follows that there would be a clear connection between the political officers of government and the non-political

DPP. In response to the question of whether this consultation is right, the DPP told the committee,

Yes, it is. The protocol that sets out how this works is agreed between the

DPP and the Attorney-General, and that is a public document. It sets out that that is a proper exercise for the Attorney-General to engage in, and also how the Attorney-General should engage in it. It makes it clear, for the Attorney-General just as for the DPP, that if he is the decision maker, he must act independently of Government, and that the decision is his.

Therefore, the exercise that he conducts is to ask other Ministers whether they have views, and if so, what their views are. Then he comes to an independent decision. That is set out in the protocol. If the Attorney-

General passed on the information to me, I would be expected to work in precisely the same way. The Attorney-General would carry out the exercise—a perfectly proper exercise. It does happen, and it is transparently provided for. I would then go through the same exercise, which is to exercise independent judgment, taking on board the serious considerations that have been given to the matter by other Ministers and the Attorney-General(House of Commons, 2011, column, n. 132).

This clear linkage between the government, Attorney General and Director of

Public Prosecutions seems to penetrate the firewall between the DPP and the political wishes of the government to ensure that the wishes of the government will prevail over the preferences of political activists. So Livni is free to come to the UK without the fiasco of 2009.Or is she? The new system came under immediate strain in 2011 when TzipiLivni announced that her delayed visit would now go ahead. Livni, at that time leader of Israel’s main opposition party,

Kadima, had scheduled meetings with UK foreign secretary William Hague. As expected, the DPP was immediately put under pressure to consent to an arrest warrant in respect of allegations of war crimes during the 2008-2009 War in

Gaza. The formal application to the DPP was made on 4 October 2011. The

CPS had been in possession of evidence supplied by NGOs against Livni for some time and now they were given more. The reply was slow in coming.

Instead, while the decision was held up through a consultation process, the government rapidly took the matter out of the DPP’s hands. On 6 October, the

Foreign Office urgently arranged diplomatic immunity by conferring ‘special mission’ status on the visit before the DPP had responded to demands from

15

Palestinian campaigners for her arrest. The outcome was that the DPP refused consent on the grounds that Livni now had diplomatic immunity (CPS,

2011a).

17 The visit went ahead without the threat of a hard or virtual court case but it does raise the question that if it was in the national interest for the visit to go ahead, why could the DPP not have been relied on to refuse his consent to

Livni’s arrest? Could it be that the DPP is not seen as reliable as the Attorney

General in implementing the particular preferences of the government of the day?

In June 2012 Doran Almog was again due to attend a charity fundraiser in the

UK. Seven years after his last abortive trip to the UK he again cancelled at the last minute on the advice of the Israeli government. Apparently the DPP could not be relied on. A senior Israeli official was quoted in the press as saying, ‘It’s true that the new British law is better than the original one, which allowed any magistrate to issue a warrant, but the government promised it would be changed so that only the Attorney-General, who is a political figure we can trust, could authorise universal jurisdiction arrests....The DPP is a civil servant who may decide that he is going to authorise arrest warrants. We are still waiting for assurances on this from the British government.’Almog was even more forthright, ‘[t]he change to the law is cosmetic and if I were to arrive tomorrow in London, the arrest warrant could still be used against me. I don’t know what the British prosecutor is going to decide’ (Pfeffer, 2012).

Conclusion

When analysing the new UK universal jurisdiction law, as well as noting what was changed, it is worth considering what was left the same.The power of the state to prosecute perpetrators of war crimes whatever their nationality and wherever those crimes are committed is unchanged. These hard cases can still be brought by the state where it is in the view of the government in the national interest to do so. The existing legal requirement for the Attorney General’s consent to prosecution, whether public or private, could be relied upon to ensure that unwelcome hard cases were never the problem.

The change was designed to tackle the ‘virtual’ cases brought by pro-Palestinian

NGOs. They had been made possible by the power of the UK citizen to obtain an arrest warrant from a judge on the basis of a prima facie case of criminality.

The threat of Israel’s politicians (other than those with immunity), military elites and military lawyers being chased around London by NGO’s with arrest warrants imposed such an intolerable legitimacy costs on the Israeli state that

16

for many years changing the UK law was high on the Israeli agenda of UK-

Israel bi-national relations. Intelligence sharing by the two countries, a role for the UK in resolution of the Israel-Palestine conflict and intelligence on Iranian nuclear proliferation are certainly valued by the UK so thatIsraeli signalling that cooperation was under threat was sufficient to bring about a change in the law and an apparent retreat from international commitments to end impunity for war crimes. While this can be seen as an external interference in the design of UK domestic law, in truth there was a coincidence of interest in controlling access to the courts. The government framed the reason for change as designed, ‘to prevent the courts being used for political purposes’. A more accurate statement would have been to prevent the courts being used for inconvenient political purposes that undermine the government’s foreign policy. In short, the change in the law was a matter of the state getting control of the universal jurisdiction to put a stop to the virtual cases brought by NGOs. This reveals the degree of governmental control of access to the jurisdiction as the key variable when examining the universal jurisdiction. If government control is absolute the inconvenient prosecutions do not even progress to the virtual stage and legal redress of human rights abuses committed abroad will be constrained by the political preferences of the government of the day. This is to subject law to politics, but then as Henry Kissinger famously put it, ‘The role of the statesman is to choose the best option when seeking to advance peace and justice, realising that there is frequently a tension between the two and any reconciliation is likely to be partial’ (Kissinger, 2001, p. 95).

18

Although the NGOs interact with the Metropolitan Police, the DPP and the

Attorney General through regular consultation, this added proximity to state power represents poor return for the loss of the independent agency that the arrest warrant procedure provided. Any weakening of the domestic legal framework for the prosecution of war crimes under the universal jurisdiction is a serious setback for the human rights networks. As might be expected, the changes in UK law have not been well received by many UK NGOs and promoters of a UK commitment to human rights (Machover, 2011).

19 From an

Israeli perspective, the threats of arrest were not just a matter of inconvenience.

The strength of the Israeli responseis best understood as a reaction to the serious damage being done to Israel’s international legitimacy.

Viewing state attitudes towards the jurisdiction in terms of an international relations cost benefit calculus, distinguishing between hard and virtual cases

17

and identifying the legitimacy costs to the state whose nationals are being threatened with prosecution all generate useful insights. But there is still the question of how much has really changed.This is not a straight- forward assessment. Looking at the broader jurisdiction, Israel would have liked the UK to limit its criminal jurisdiction to crimes involving its own nationals, but that was never on the cards. There is power in the call to end impunity for war crimes and thecommitment to human rights within the coalition government would never have allowed the wholesale abandonment of Britain’s international obligation to prosecute offenders.

Certainly, from an Israeli perspective, the change is preferable to what had gone before. But the government has not seized complete control of the jurisdiction.

The power to prevent the virtual cases is now in the hands of the DPP, an independent law officer, and Tel Aviv would rather have seen the Attorney

General decide. This is a new power for the DPP and whatever the assurances, as was seen by the panic over Tzipi Livni’s 2011 visit and the cancellation of

Almog’s the following year, there is no certainty that this DPP or his successors will attach the same importance as the government to promoting London as a centre for Middle East diplomatic negotiations or, for that matter, intelligence sharing. Balancing human rights and national interest remains as uncertain as ever. Viewed from this perspective it can be seen that Israel may have been instrumental in bringing about a change in UK law but not the change that Tel

Aviv wanted. The CPS continues to meet with the NGOs whilethe Metropolitan

Police Terrorism Command (SO15) investigates allegations of war crimes in

Gaza by Israel’s politicians, military commanders and military lawyers. The commitment of successive UK governments to the bi-lateral relationship means that prosecutions are unlikely but Israel cannot safely ignore the UK’s commitment to international law and there will be more cancelled trips.

Bibliography

AGO, CPS, SFO, & Revenu and Customs Prosecutions Office (2009). Protocol between the Attorney General and the Prosecuting Departments Retrieved

19.11.2012, from http://www.attorneygeneral.gov.uk/Publications/Documents/Protocol between the Attorney General and the Prosecuting Departments.pdf

Black, I. (2009, 15 December). UK to review war crimes warrants after Tzipi

Livni arrest row . The Guardian .

18

Clark, I. (2005). Legitimacy in International Society . Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

CPS (2011a). CPS Statement in relation to Ms Livni’s visit Retrieved

15.11.2012, from http://www.cps.gov.uk/news/press_statements/_cps_statement_in_relatio n_to_ms_livni_s_visit/

CPS (2011b). War Crimes Referral Guidelines Retrieved 12.11.2012, from http://www.cps.gov.uk/publications/agencies/war_crimes.html d’Asperemont, J. (2011). Multilateral Versus Unilateral Exercises of Universal

Criminal Jurisdiction. Israel Law Review, 43 , 301-318.

Fletcher, G. (2003). Against Universal Jurisdiction. Journal of International

Criminal Justice, 1 , 580-584.

Gallagher, K. (2009). Universal Jurisdiction in practice; Efforts to hold Donald

Rumsfeld and other high-level United States Officials Accountable for

Torture. Journal of International Criminal Justice,, 7 (229), 1087-1116.

General Assembly. Principle of ‘Universal Jurisdiction’ Again Divides

Assembly’s Legal Committee . from http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2011/gal3415.doc.htm.

Glick, C. (2005, 15 September). Gaza’s Long Shadow . Jerusalem Post .

Goldsmith, J., & Posner, E. (2005). The Limits of International Law . Oxofrod:

Oxford University Press.

Harriet Sherwood (2011, 3 November 2011). Israel Sparks Legal Row During

Hague’s Visit . The Guardian . Retrieved 28 October 2012 from athttp://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/nov/03/israel-war-crimes-rowwilliam-hague.

House of Commons (2011). Public Bill Committee, Police Reform and Social

Responsibility Bill - Fourth Sitting, from http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201011/cmpublic/policerefo rm/110120/pm/110120s01.htm

Human Rights Watch (2006). Universal Jurisdiction in Europe. Retrieved from http://www.hrw.org/en/node/11297/section/4.

Kissinger, H. (2001). The Pitfalls of Universal Jurisdiction: Risking Judicial

Tyranny. Foreign Affairs, (July/August), 86-96.

Langer, M. (2011). The diplomacy of Universal Jurisdiction: the political branches and the transnational prosecution of international crimes.

American Journal of international Law, Vol. 105 , 1-49.

Machover, D. (2011, 30 March). Arrest warrant plans make a mockery of universal jurisdiction . The Guardian . from athttp://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2011/mar/30/coalitioncriminal-justice-universal-jurisdiction. .

Machover, D. (2012, 6 August). Fear of Fair Trials Fuels the Israeli Offensive

Against Lawfare . Huffington Post . from

19

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/daniel-machover/fear-of-fair-trialsfuels_b_409796.html.

O’Keefe, R. (2004). Universal Jurisdiction; Clarifying the Basic Concept.

Journal of International Criminal Justice, 2 (3), 735-760.

Owen Bowcott (2011, 6 October ). Tzipi Livni spared war crime arrest threat.

Foreign Office declares that the Israeli opposition leader enjoys temporary diplomatic immunity as she is on a special mission . The

Guardian .

Pfeffer, A. (2012, 31 May). IDF man Almog cancels charity trip over universal jurisdiction fear . Jewish Chronicle . Retrieved 3 November 2012, from http://www.thejc.com/news/uk-news/68298/idf-man-almog-cancelscharity-trip-over-universal-jurisdiction-fear.

R (on the application of Corner House Research and others) (Respondents) v

Director of the Serious Fraud Office (Appellant) (Criminal Appeal from Her

Majesty’s High Court of Justice), [2008] UKHL 60

REDRESS/FIDH (2010). Extraterritorial Jurisdiction in the European Union, a

Study of the Laws and Practice in the 27 Members States of the European

Union. Paris: REDRESS/FIDH.

Reut Institut (2010). Building a Political Firewall against the Assault on Israel's

Legitimacy London as a Case Study’ Available from http://www.reutinstitute.org/data/uploads/PDFver/20101219 London Case Study.pdf

Reydams, L. (2003). Universal Jurisdiction: International and Municipal Legal

Perspectives . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Reydams, L. (2011). The Rise and Fall of the Universal Jurisdiction. In W.

Schabas & N. Bernaz (Eds.), Handbook of International Criminal Law .

London: Routledge.

Rosenzweig, I., & Shany, Y. (2009). Establishment of a Legal Department by the Israeli Security Cabinet to Deal with Issues of International

Jurisdiction. Terrorism and Democracy, (12). Retrieved from http://en.idi.org.il/analysis/terrorism-and-democracy/issue-no-12,december-2009/establishment-of-a-legal-department-by-the-israelisecurity-cabinet-to-deal-with-issues-of-international-jurisdiction/

Roth, K. (2001). The Case for Universal Jurisdiction. Foreign Affairs,

September/October .

Rozenberg, J. (2011, 26 January). DPP’s power to block war crimes arrest is in the public interest . The Guardian . from http://www.guardian.co.uk/law/2011/jan/26/dpp-war-crimes-publicinterest.

Various Authors (2012). Special Issue: War by other means: Israel and its detractors. Israel Affairs, 18 (3).

20

Endnotes

1 For an excellent discussion of the jurisdiction see Reydams (2003) and O’Keefe (2004)

For a negative assessment see Kissinger (2001), and reply by Roth (2001) and Fletcher (2003). For a survey of

EU Extra-territorial Jurisdiction of the EU see the report by REDRESS/FIDH (2010)and for a review of EU approaches see Human Rights Watch (2006)

2 For a useful survey of the jurisdiction see Human Rights Watch (2006)

3 Luc Reydams distinguishes between the jurisdiction that arises from international conventions that oblige states to try or extradite and the jurisdiction that requires prosecution on the basis that the former can be seen as a multilateral exercise of the jurisdiction and the latter unilateral, see Reydams (2011).

4 Jean d’Asperemont argues that such unilateral application of the jurisdiction undermines the legitimacy of the prosecutions on the grounds that the universality principle lacks domestic legitimacy. See d’Asperemont (2011).

5 See a special issue of Israel Affairs by Various Authors (2012) and the report published by the Reut Institut

(2010)

6 Criminal Justice Act 1988 (torture);Piracy Act 1837 (piracy); Taking of Hostages Act 1982 (hostagetaking);Internationally Protected Persons Act 1978 (attacks and threats of attacks on protected persons);

Aviation Security Act 1982 (hijacking etc);Nuclear Material (Offences) Act 1983 (offences relating to nuclear material);Aviation and Maritime Security Act 1990 (endangering safety at aerodromes and hijacking ships);United Nations Personnel Act 1997 (attacks on UN workers etc.); War Crimes Act 1991 (WWII war crimes).

7 See, the Protocol Between the Attorney General and the Prosecuting Departments by (AGO, et al., 2009)

[particularly section 4(e) ‘Seeking Ministerial Representations in the Public Interest’].

8 The right of the citizen to prosecute is codified in Section 6 (1) of the Prosecution of Offences Act 1985.

9 Section 1 of the Magistrates’ Courts Act 1980provides: (1) On an information being laid before a justice of the peace that a person has, or is suspected of having, committed an offence, the justice may issue - (a) a summons directed to that person requiring him to appear before a magistrates’ court to answer the information, or (b) a warrant to arrest that person and bring him before a magistrates’ court.

10 The “War Crimes/Crimes against Humanity Referral Guidelines” set out criteria for the SO15 to decide whether to initiate an investigation against a specific suspect, taking into account the nationality and location of the suspect, availability of evidence, including victims and witnesses, as well as the advice of the Crown

Prosecution Service (CPS) in relation to legal issues such as immunity and jurisdiction (CPS, 2011b).

11 Author’s interview with Machover, London 17 August 2007.

12 The breadth of opposition was demonstrated by a letter to the Guardian signed by over 70 influential opponents of the Bill, see ( The Guardian, 13 December 2010)

13 S153 Police Reform and Social Responsibility Act 2011 amends the legislation concerning public prosecutions,‘[w]here a person who is not a public prosecutor lays an information before a Justice of the Peace in respect of an offence to which this section applies, no warrant shall be issued under this section without the consent of the Director of Public Prosecutions’.

14 Constitutionally, the Crown prosecution Service, headed by the DPP, is a government department without a ministerial head. The DPP is appointed by and under the supervision of the Attorney General who reports directly to Parliament. The arrangement is designed to distance the day to day prosecution of offences from government interference.

21

15 Enquiries of the CPS reveal that the following organisations attended the meetings: REDRESS, FIDH,

UKBA, Metropolitan Police, Amnesty International, Hickman & Rose Solicitors, Global Witness, Aegis Trust,

Human Rights Watch and Justice

16 References in the text to Starmer’s explanation of his role to Parliament refer to his evidence to the House of

Commons (2011, pp. 123-124).

17 See also Aljazeera (19 October 2011) and Owen Bowcott (2011). On diplomatic immunity generally, see the

Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations 1961.

18 For a critical response see Roth (2001)

19 For an alternative view, see Rozenberg (2011)

22