Review - Department of Public Expenditure and Reform

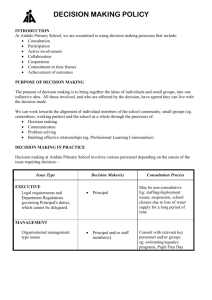

advertisement

Open Government Partnership Action 2.1 – ‘Review national and international practice to develop revised principles/code for public engagement/consultation with citizens, civil society and other by public bodies’ 1. Reaching Out – Guidelines on Consultation for Public Sector Bodies (2005) These guidelines were developed subsequent to the White Paper, ‘Regulating Better’, and under the principle of transparency which was one of the six core principles that Government will take into account when considering proposals for new regulations and regulatory change. The guidelines were published by the Regulatory Reform Unit, Department of the Taoiseach. Their aim was to promote better quality consultation across the Public Service. They stated that ‘a key challenge is the need for rigorous, evidence-based policy-making. These processes need to be based on good quality information, both statistical and qualitative, and consultation is one of the most important ways of accessing such information. Consultation is also a crucial element in the design, delivery and improvement of services’. These guidelines are aimed primarily at providing guidance for the management of once-off consultation processes. They provide options in designing consultations, set out the reasons why Public Service bodies would consult, provide details on planning a consultation and managing the process including the strengths and weakness of different methods of consultation, as well as details on analysing and interpreting the results, on acknowledgement, feedback and publication of submissions. The guidelines provide a lot of detail (including a checklist and flowchart) on the consultation process, and how to plan, manage, analyse it effectively. These guidelines are now ten year old and reflect the context of 2005 including referencing social partnership process and structures, and pre-social media ICT tools. As they are primarily focused on process, they do not provide details on issues such as when to consult, and principles of good consultation. In addition, they are not definitive regarding a minimum consultation period, timelines for the provision of feedback or how and in what way feedback should be given [e.g. the guidelines state the ‘giving feedback to those who have taken part in consultation reassures participants that their views have been taken into account and it reinforces the benefits of dialogue between them and consulting bodies’. It further states to ‘consider how feedback to those who have taken part in consultation will be handled. Will consultations be published? Will responses to consultation be given and/or published?’] 2. International Experience UK In the UK a Code of Practice on Consultation has been in place since 2000, and was updated in 2008. These were produced by the Better Regulation Executive, Department of Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform. In 2012, the Code was replaced by consultation principles (3 page document) that Government Departments and other public bodies should adopt for engaging stakeholders when developing policy and legislation – https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/255180/Con sultation-Principles-Oct-2013.pdf. These principles are clear, and briefly described. This was an approach to improve the way Government consults by adopting a more proportionate and targeted approach. The governing principle is proportionality of the type and scale of consultation to the potential impacts of the proposal or decision being taken, and thought should be given to achieving real engagement rather than merely following bureaucratic process. It follows on from the Civil Service Reform Plan which commits the government to improving policy making and implementation with a greater focus on robust evidence, transparency and engaging with key groups earlier in the process. The emphasis of these Principles is on understanding the effects of a proposal and focusing on real engagement with key groups rather than following a set process. The key Consultation Principles are: departments will follow a range of timescales rather than defaulting to a 12week period, particularly where extensive engagement has occurred before (‘the amount of time required…..might typically vary between 2 and 12 weeks. The timing and length of a consultation should be decided on a case-by-case basis’); departments will need to give more thought to how they engage with and use real discussion with affected parties and experts as well as the expertise of civil service learning to make well informed decisions (‘consideration should be given to more informal forms of consultation that may be appropriate…rather than always reverting to a written consultation’) ; departments should explain what responses they have received and how these have been used in formulating policy (‘consultation responses should usually be published within 12 weeks of the consultation closing’. An example of such a response is at https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/changes-tothe-police-disciplinary-system); consultation should be ‘digital by default’, but other forms should be used where these are needed to reach the groups affected by a policy; and the principles of the Compact1 between government and the voluntary and community sector will continue to be respected. The Consultation Principles state that ‘engagement should begin early in policy development when the policy is still under consideration and views can genuinely be taken into account. Every effort 1 Compact is an agreement which governs relations between the government and civil society organisations in England - https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-and-voluntary-sector-agree-new-compact should be made to make available the Government’s evidence base at an early stage to enable contestability and challenge.’ They further state that ‘to avoid creating unrealistic expectation, it should be apparent what aspects of the policy being consulted on are open to change and what decisions have already been taken.’ In the UK, all consultations are housed on the Government’s single web platform https://www.gov.uk/government/publications?publication_filter_option=consultations. This means that all public consultations across Government are accessible in one location, and can be sorted by department, topic or open/closed consultations. In addition, the 2012 guidance does not have legal force and does not prevail over statutory or mandatory requirements. It is interesting to note that the 2008 Code of Practice on Consultation was criticised as public service organisations were not obliged to adopt it, and it did not apply to consultation exercises run by them unless they explicitly adopted it. The 2012 Consultation Principles state that they should be adopted by Departments and public bodies. Australia Similar to the UK’s but more descriptive, Australia produced a Guidance Note on ‘Best Practice Consultation’ (July 2014) http://www.dpmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/002_Best_Practice_Consultation.pdf This short 11 page document from the Office of Best Practice Regulation, Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, is based on two principles i.e. policy makers should consult in a genuine and timely way with affected business, community organisations and individuals, and policy makers must consult with each other to avoid creating cumulative or overlapping regulatory burdens. The context for these principles is the Regulation Impact Statement. The Guidance Note is complemented by a web guide that outlines the various tools available for low-cost and wide scale online consultation, and by a business consultation website (www.consultation.business.gov.au) where consultation information is posted and stakeholders can provide feedback. This website also appears to provide details of all current public consultations, and automatically notifies businesses and government agencies of consultations in areas where they have registered an interest. The Guidance Note states that ‘a genuine consultation process ensures that you have considered the real-world impact of your policy options.’ It outlines four consultation options and when each is appropriate: full public, targeted, confidential and post-decision. It also highlights the elements of a consultation plan. Full consultation is considered the appropriate level of consultation for all proposals unless a compelling case is made for a limited form of consultation (such as a need for confidential consultation because of market sensitivity). Consultation should be conducted early when the policy objectives and different approaches to regulation are still under consideration. The Guidance Note also sets out a number of characteristics for the application of consultation processes: continuous – consultation should be continuous and should start as early as possible. It should continue through all stages of the regulatory cycle; broad-based – consider the scope of the proposed regulatory changes and consult widely to ensure that consultation captures the diversity of stakeholders affected by the changes; accessible – consultation should ensure that stakeholders can readily contribute to policy development, and stakeholders should be informed by the most appropriate means. A range of strategies should be considered to assist stakeholders who are expected to be significantly affected, but who do not have the resources or capability to participate in the consultation process. Consultation can take a variety of forms other than written consultation, such as stakeholder or public meetings, working groups, focus groups, surveys or web forums (such as blogs or wikis); not burdensome – not to make unreasonable demands of people you wish to consult or assume that they have unlimited time to devote to the consultation process. Timeframes should be realistic to allow stakeholders enough time to provide a considered response, and time required will depend on the specifics of the proposal. Be aware of the burden that the whole government may be placing on stakeholder groups; transparent – explain the objectives of and the context for the consultation, as well as when and how the final decisions will be made. State any aspects of the proposal that have already been finalised and will not be subject to change. Information or issues papers should, where possible and appropriate, be made available to enable informed comments. Show stakeholders how the consultation responses have been taken into consideration. consistent and flexible – consistent consultation procedures make it easier for stakeholders to participate; subject to evaluation and review – evaluate consultation processes, and continue to examine ways of making them more effective; not rushed – the aim is effective consultation and ‘real listening’. Provide realistic timeframes for participants to contribute. Depending on the significance of the proposal, between 30 and 60 days is usually appropriate for effective consultation. a means rather than an end – consultation should be used as a way to improve decisions, not as a substitute for making decisions. Canada In 2009, Canada produced ‘Guidelines for Effective Regulatory Consultations’ http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/rtrap-parfa/erc-cer/erc-cer01-eng.asp This Guide focuses on regulatory consultation, and it states that consultation should be woven into all aspects of policy development, including the discussions as to which instrument (i.e. legislation, regulations, voluntary mechanisms, guidelines, or policy) would best meet the public policy objectives. This is illustrated by the graphic under:- This Guide details the components of effective regulatory consultations, these include: - ongoing, constructive, and professional relationship with stakeholders. It states that the following principles will help to achieve this relationship: o meaningfulness. Officials conducting the consultation should be open to stakeholders’ views and opinions and take these into account in preparing the proposed regulations. If some aspects of the proposal are not subject to change, this should be clearly communicated. There should be clarity regarding the purpose and objectives of the consultation; o openness and balance – all stakeholders should have an opportunity to contribute their views, and significant effort should be made to identify the most affected stakeholders; o transparency – officials should ensure transparency of: the overall regulatory consultation process; pertinent non-sensitive information; the decision-making process; and how stakeholder input will be used. o accountability – demonstrate accountability by documenting how the views of stakeholders were considered during the development of the regulations and informing stakeholders of how those views were used. Where stakeholder input could not be reflected in the proposed regulations, officials should be able to outline the reasons why. - a clear and comprehensive consultation plan. This plan should state the objectives of the process and include issues under review, a public environment analysis, key participants, timelines, internal and external coordination, a mechanism for reporting consultation results, proposed consultative approach, evaluation (ongoing and end of process), and feedback and follow-up. For each of these elements, the Guide provides a useful checklist, and a detailed ‘how to’ guide. - conducting the consultations. This involves communicating neutral, relevant, and timely information related to the proposals, and ensuring that officials have the necessary skills to conduct consultations. Netherlands Since 2006 the Dutch administration has followed a code of conduct for professional consultation, which contains 10 principles: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Indicate who is finally responsible and commit this official to the process. Make a procedural plan beforehand and publish it. Get to know and mobilise all stakeholders in the policy. Organise relevant knowledge together and make this transparent. Be a trustworthy discussion partner. Communicate clearly, at the right time and with modern means. Be clear about roles and results on advice to be expected. Obligations for the consultants may be demanded concerning quality and energy devoted to their advice. 9. Be accountable about the follow-up. 10. Consultation is not to be done just for the sake of it, additional value must be expected – however, if government refrains from consultation, this must be motivated. The impact and effectiveness of this Code has been studied2 and it has been found that a professional approach appears to lead to better impact of citizen engagement. It was found that good communication leads to greater impact. Participants are more satisfied with the process and the results if there is clear communication about the influence participants have, if what happens with results is clearly accounted for. Additionally, the Netherlands committed, as part of its Open Government Action Plan 3, to enhanced use of online consultation to inform and consult with citizens on planned legislation and policy documents. In 2009 a dedicated website for online public consultation was launched4 and has been used in over 250 consultations on new legislation. 2 (OECD) 2009. Focus on Citizens: Public Engagement for Better Policy and Services. Paris: OECD. file:///C:/Users/swaines/Downloads/Netherlands%20Action%20Plan%20Open%20Government%20Partnershi p.pdf 4 www.internetconsultatie.nl 3 Czech Republic Since 2007, the Czech Republic has required publication of all legislative documents prior to their discussion by Government. This was achieved by launching a central government website where all draft policy documents scheduled for the submission to Government are published in advance and to which public comments can be sent. Based on a set of Principles of Public Engagement approved in 2006, a Methodology for Public Consultation was adopted (Government resolution No. 879/2007) to enlarge the scope and possible approaches to public consultation during policy making.5 This methodology defines a minimal standard for public participation in policy making. It describes forms of public participation (formal/informal consultation, round tables, public meetings, working groups etc), provides approaches for the identification of target groups, minimum time schedules and ex post evaluation. Its implementation is planned in two phases – an initial pilot period (until end 2008) followed by general application (from 2009). The Ministry of Interior will review the results at the end of the pilot period Council of Europe In 2009, the Council of Europe produced a ‘Code of Good Practice for Civil Participation in the Decision-Making Process’ - http://www.coe.int/t/ngo/Source/Code_English_final.pdf. This document is general in nature, and states that ‘consultation is relevant for all steps of the decision-making process, especially drafting, monitoring and reformulation’. It sets out principles for civil participation which include: participation (processes for participation are open and accessible, based on agreed parameters for participation); trust (implying transparency, respect and mutual reliability); accountability and transparency; and independence (right of NGOs to act independently and advocate positions different from the authorities with whom they may otherwise co-operate). This Code provides a useful matrix (under) setting out the steps of the political decisionmaking process and their connection with levels of participation. It is based on good practices and examples form civil society across Europe. The levels of participation at each point in the decision-making process may vary from low to high and it is intended that the suggested tools are used as ways to implement each type of participation. It also shows how the tools mentioned may achieve the intended level of participation at each step in the decisionmaking process. 5 file:///C:/Users/swaines/Downloads/Methodology_for_Public_Consultation.pdf OECD Based on the results of a survey of its member countries6, the OECD believes that a “one size fits all” approach to policy making and consultation is clearly not an option. To be effective, open and inclusive, policy making must be appropriately designed and context-specific for a given country, level of government and policy field. At the same time, a commonly agreed set of principles can guide practitioners when designing, implementing and evaluating open and inclusive policy making. The OECD advises countries to: - Mainstream public engagement to improve policy performance; - Develop effective evaluation tools; - Leverage technology and the participative web; and - Adopt sound principles to support practice. 6 (OECD) 2009. Focus on Citizens: Public Engagement for Better Policy and Services. Paris: OECD. The OECD has devised a set of ten robust principles7 validated by comparative experience and extensive international policy dialogue among government officials from OECD member countries. They are an expression of the cumulative experience of OECD member countries and serve as a common basis upon which all countries may draw when designing policies, programmes and measures for open and inclusive policy making and service delivery which are appropriate to their own national context. 1. Commitment: Leadership and strong commitment to open and inclusive policy making is needed at all levels – politicians, senior managers and public officials. 2. Rights: Citizens’ rights to information, consultation and public participation in policy making and service delivery must be firmly grounded in law or policy. Government obligations to respond to citizens must be clearly stated. Independent oversight arrangements are essential to enforcing these rights. 3. Clarity: Objectives for, and limits to, information, consultation and public participation should be well defined from the outset. The roles and responsibilities of all parties must be clear. Government information should be complete, objective, reliable, relevant, easy to find and understand. 4. Time: Public engagement should be undertaken as early in the policy process as possible to allow a greater range of solutions and to raise the chances of successful implementation. Adequate time must be available for consultation and participation to be effective. 5. Inclusion: All citizens should have equal opportunities and multiple channels to access information, be consulted and participate. Every reasonable effort should be made to engage with as wide a variety of people as possible. 6. Resources: Adequate financial, human and technical resources are needed for effective public information, consultation and participation. Government officials must have access to appropriate skills, guidance and training as well as an organisational culture that supports both traditional and online tools. 7. Co–ordination: Initiatives to inform, consult and engage civil society should be coordinated within and across levels of government to ensure policy coherence, avoid duplication and reduce the risk of “consultation fatigue. ”Co-ordination efforts should not stifle initiative and innovation but should leverage the power of knowledge networks and communities of practice within and beyond government. 8. Accountability: Governments have an obligation to inform participants how they use inputs received through public consultation and participation. Measures to ensure that the policy-making process is open, transparent and amenable to external scrutiny can help increase accountability of, and trust in, government. 9. Evaluation: Governments need to evaluate their own performance. To do so effectively will require efforts to build the demand, capacity, culture and tools for evaluating public participation. 10. Active citizenship: Societies benefit from dynamic civil society, and governments can facilitate access to information, encourage participation, raise awareness, strengthen 7 Ibid. at pg. 17 citizens’ civic education and skills, as well as to support capacity-building among civil society organisations. Governments need to explore new roles to effectively support autonomous problem-solving by citizens, CSOs and businesses. European Commission The European Commission has published General Principles and Minimum standards for consultation of interested parties by the Commission8. The principal aims of the approach can be summarised as follows: To encourage more involvement of interested parties through a more transparent consultation process, which will enhance the Commission’s accountability. To provide general principles and standards for consultation that help the Commission to rationalise its consultation procedures, and to carry them out in a meaningful and systematic way. To build a framework for consultation that is coherent, yet flexible enough to take account of the specific requirements of all the diverse interests, and of the need to design appropriate consultation strategies for each policy proposal. To promote mutual learning and exchange of good practices within the Commission. The ‘general principles’ are identified as participation, openness and accountability, effectiveness and coherence.9 The ‘minimum standards’ are as follows10: 1. Clear content of the consultation process: All communications relating to consultation should be clear and concise, and should include all necessary information to facilitate responses. 2. Consultation Target Groups: When defining the target group(s) in a consultation process, the Commission should ensure that relevant parties have an opportunity to express their opinions. 3. Publication: The Commission should ensure adequate awareness-raising publicity and adapt its communication channels to meet the needs of all target audiences. Without excluding other communication tools, open public consultations should be published on the Internet and announced at the “single access point”. 4. Time limits for participation: The Commission should provide sufficient time for planning and responses to invitations and written contributions. The Commission should strive to allow at least 8 weeks for reception of responses to written public consultations and 20 working days’ notice for meetings. 5. Acknowledgement and feedback: Receipt of contributions should be acknowledged. Results of open public consultation should be displayed on websites linked to the single access point on the Internet. 8 http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2002:0704:FIN:en:PDF Ibid. at pg. 16-18 10 Ibid. at pg. 19-22 9