Endings (PP)

advertisement

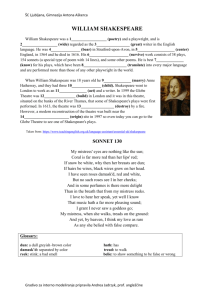

‘Is this the promised end?’ (King Lear, 5.3.238): The Stagecraft of Shakespeare’s Endings 26.10.15 Prologue: Hamlet gets jiggy Why, let the stricken deer go weep, The hart ungalled play, For some must watch, while some must sleep, So runs the world away. (3.2.234-237) • Would not this [his performance of the song], sir, and a forest of feathers, if the rest of my fortunes turn Turk with me, with two Provencal roses on my razed shoes, get me a fellowship in a cry of players, sir? Jigging Noun †4. A light performance or entertainment of a lively or comical character, given at the end, or in an interval, of a play. Obs. Perhaps originally mainly consisting of song and dance (quot. 1632), but evidently sometimes of the nature of a farce. Verb 2. a. intr. To move up and down or to and fro with a rapid jerky motion; in quot. 1886 of a fish = JIGGER v.1 1604 SHAKESPEARE Hamlet III. i. 147 You gig [1623 gidge] & amble, and you list you nickname Gods creatures, and make your wantonnes ignorance. The Eschatology of Endings (eschatology = a. The department of theological science concerned with ‘the four last things: death, judgement, heaven, and hell’.) ‘I would give you some violets, but they withered all when my father died. They say a made a good end’. Ophelia, 4.5.182 The Eschatology of Endings • ‘The world is a stage, life is the play: we come on, look about us, and go off again’. Democritus (4thC BC) • God is the ‘Author of all our Tragedies,’ a playwright who ‘hath written out and appointed what every Man must play’. ‘Death is the end of the Play, and takes from all’. Sir Walter Ralegh, History of the World (pub.1614) Hardwiring? Birth, copulation and death That’s all the facts when you come to brass tacks Birth, copulation and death ‘Sweeney Agonistes’, T.S. Eliot 19 of Shakespeare’s plays feature the death of a major character within the last seven minutes or so of stage action. Most of the other half end in the prospect of marriage and/or some form of reunion or reconciliation A Theory of Endings? Our composition must be more accurate in the beginning and end, than in the midst; and in the end more, than in the beginning; for through the midst the stream bears us. Ben Jonson, Discoveries (pub.1641) Accurate = 1. Executed with care; careful. Shakespeare’s Careless Endings? •In many of his plays the latter part is evidently neglected. When he found himself near the end of his work, and in view of his reward, he shortened the labour to snatch the profit. He therefore remits his efforts where he should most vigorously exert them, and his catastrophe is improbably produced or imperfectly represented. •Samuel Johnson, 1765 Theatre as durational art form Like as the waves make towards the pebbled shore, So do our minutes hasten to their end; Each changing place with that which goes before, In sequent toil all forwards do contend. Sonnet 60 Mortality / running time / endings The Craft of Endings: some questions and tentative answers 1) How long does an ending last? Final scene average: 240 lines or c.16 minutes (working on assumption that it takes roughly one hour to speak 900 lines at pace) 2) What is the average length of the closing speech act? 9.25 lines Contrast genre; compare Macbeth and Richard III: final scenes are the shortest in the canon and are near-identical – the tyrant has been slain and his successor defines the terms of the regime change; as Malcolm says, ‘We shall not spend a large expense of time’ and neither he nor Richmond do – 41 lines to be exact. The Ending of the Dream A Midsummer Night’s Dream: a play which doesn’t quite know how to stop, offering a superabundance of closural devices – bergamask, Theseus’s apparently concluding ‘off to bed’ speech; the dance of the fairies with Oberon and Titania… and, finally,… Puck’s epilogue. The Craft of Endings: some questions and tentative answers 2) What is the average length of the closing speech act? 9.25 lines 3) Who speaks it? A male character not impossible that the same actor played Fortinbras, Edgar, Malcolm and Octavius Caesar – the last of whom closes both Julius Caesar and Antony and Cleopatra. The case is altered with the Romances – largely because the established authority figure and the lead actor has survived the plot: it was presumably Richard Burbage – as Pericles, Leontes and Prospero – who enjoyed the privilege of vocally closing those late plays. The Craft of Endings: some questions and tentative answers 4) What time elapses between the death of a major character and the end of the play? Average = 64 lines In Shakespeare’s two earliest tragedies – Titus Andronicus and Romeo and Juliet – more than twice the average length expires; notoriously in Romeo the Friar alone spends 31 lines telling the audience what it already knows: ‘I will be brief’! In mature tragedies Othello and King Lear, only 16 lines, roughly 1 minute, elapses between the death of the titular hero and the death of the play. The final tragedy Coriolanus is comparably terse and abbreviated. 5) How many plays end in rhyming couplets? Approx. 75% or three in four The Craft of Endings: some questions and tentative answers 6) How many plays end with the promise of offstage discussion? At least 14 7) How many plays end with an epilogue or a jig? Impossible to say, but 10 epilogues survive in print Thomas Platter: September 1599: went to ‘the house with the thatched roof’ and watched ‘the tragedy of the first emperor Julius Caesar’: “At the end of the comedy, according to their custom, they danced with exceeding elegance, two each in men’s and two in women’s clothes, wonderfully together.” Plays within plays – various models of endings Henry IV, 1: Banish plump Jack, and banish all the world. I do, I will. [Knocking within] Hamlet: Polonius: Give o’er the play Dream: Bottom: Will it please you to see the epilogue or to hear a bergamask dance between two of our company Theseus: No epilogue, I pray you; for your play needs no excuse. Epilogues: Henry IV, Part Two [spoken by a Dancer] Excusing the play: First my fear; then my courtesy; last my speech. My fear is, your displeasure; my courtesy, my duty; and my speech, to beg your pardons. Paying the debt: If my tongue cannot entreat you to acquit me, will you command me to use my legs? and yet that were but light payment, to dance out of your debt. Gesturing forward: One word more, I beseech you. If you be not too much cloyed with fat meat, our humble author will continue the story, with Sir John in it, and make you merry with fair Katharine of France: where, for any thing I know, Falstaff shall die of a sweat, unless already a' be killed with your hard opinions Epilogue to Henry V Thus far with rough and all-unable pen Our bending author hath pursued the story, In little room confining mighty men, Mangling by starts the full course of their glory. Small time, but in that time most greatly lived This star of England. Fortune made his sword, By which the world's best garden he achieved. And of it left his son imperial lord. Henry the Sixth, in infant bands crowned king France and England did this king succeed, Whose state so many had the managing That they lost France and made his England bleed, Which oft our stage hath shown – and, for their sake, In your fair minds let this acceptance take. Of Alternative Endings: King Lear – Quarto (1608) Lear. And my poore foole is hangd, no, no life, why should a dog, a horse, a rat of life, and thou no breath at all, O thou wilt come no more, neuer, neuer, neuer, pray you vndo this button, thanke you sir, O, o, o o. Edg. He faints my Lord, my Lord. Lear. Breake hart, I prethe breake. King Lear – Folio (1623) The last lines of King Lear The weight of this sad time we must obey, Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say. The oldest hath born most; we that are young Shall never see so much, nor live so long. Exeunt with a dead march [s.d. Folio only] Albany in Quarto (published 1608) Edgar in Folio (published 1623) The new puritanism? For a variety of reasons theatrical professionals continue to be unsatisfied with the closing moments of Shakespeare’s plays as scripted in the Folio and the Quartos, so that a playgoer is especially likely to encounter some form of rescripting in Act 5. (Alan Dessen, Rescripting Shakespeare, p.109) Henry Irving’s end to Hamlet: Good night, sweet Prince, And flights of angels sing thee to thy rest… Whiles I behind remain to tell the tale Which shall hereafter make the hearers pale. George Bernard Shaw Preface to Cymbeline Refinished (1936) The final act was merely ‘a tedious string of unsurprising dénouements sugared with insincere sentimentality after a ludicrous stage battle’. As Shaw pointed out in the same preface, there has also been a long tradition of improving the ends of Shakespeare’s plays by ‘supplying them with what are called happy endings’, a practice that has ‘always been accepted without protest by British audiences’. The theatre’s defence against puritanism: A production is only correct at the moment of its correctness, and only good at the moment of its success. In its beginning is its beginning, and in its end its end. Peter Brook UNEXPECTED ENDINGS… Globe Burning: 29 June 1613 King Henry making a Masque at the Cardinal Wolsey's house, and certain cannons being shot off at his entry, some of the paper or other stuff, wherewith one of them was stopped, did light on the thatch, where being thought at first but idle smoak, and their eyes more attentive to the show, it kindled inwardly, and ran round like a train, consuming within less than an hour the whole house to the very ground. This was the fatal period of that virtuous fabrick, wherein yet nothing did perish but wood and straw, and a few forsaken cloaks; only one man had his breeches set on fire, that would perhaps have broyled him, if he had not by the benefit of a provident wit, put it out with a bottle of ale." Sir Henry Wotton, letter dated 2nd July 1613 Shakespeare Memorial Theatre fire 1926 Astor Place Riots, New York City: 10th May 1849 Epilogue: Endings in the early modern theatre had a theological dimension Far from being careless, Shakespeare deliberately experimented with different forms of dramatic (non)closure throughout his career, sometimes providing more than one ending for the same play (e.g. Lear) Shakespeare often embeds an interpretive (and post-performance community-building?) injunction at the end of his plays The playtext is a radically incomplete form of writing and the performance does not end with language This incompletion demands that theatrical practitioners exceed the text and shape their own endings It’s hard to say exactly when the performance ends (applause; exiting the theatre; memory) In the modern theatre, the ending is one of the key moments in which the director asserts her authority / interpretive stamp on the production… [All statistics should be treated with caution and require interpretation]