Engaging young people with conflict through the

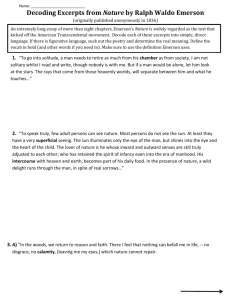

advertisement

Engaging young people with conflict through the narratives of former combatants in Northern Ireland Lesley Emerson School of Education Queen’s University Belfast l.emerson@qub.ac.uk Overview • Education in transitional contexts – Focus on North(ern/of) Ireland – Focus on history and citizenship education – Foregrounding conflict • ‘Prison to Peace’: programme • ‘Prison to Peace’: impact evaluation Overview • Participatory • Interactive • Reflective Education in transitional contexts • Paradoxical role of education in conflict-affected societies (Bush and Saltarelli 2000; Smith and Vaux 2003) • Education should seek to: – develop understanding of the nature of conflict and to assist in its resolution (Tawil and Harley 2004) – play a role in ‘narrowing the space for permissible lies’ (Ignatieff 2003, 78) by ensuring that past grievances are addressed (McEvoy (Emerson), 2007) in order that potential misrepresentation of the past does result in conflict reappearing in future generations (Cohen 2001). Education in transitional contexts • Paradoxical role of education in conflict-affected societies (Bush and Saltarelli 2000; Smith and Vaux 2003) • Education should seek to: – develop understanding of the nature of conflict and to assist in its resolution (Tawil and Harley 2004); – play a role in ‘narrowing the space for permissible lies’ (Ignatieff 2003, 78) by ensuring that past grievances are addressed (McEvoy (Emerson), 2007) in order that potential misrepresentation of the past does result in conflict reappearing in future generations (Cohen 2001). Education in transitional contexts: North(ern/of) Ireland • Partition of Ireland in 1921 and the creation of a new ‘Northern Ireland’ jurisdiction. • An inbuilt Protestant ruling majority aligned to a largely Unionist/Loyalist political agenda and a small Catholic minority aligned to a largely Nationalist/Republican agenda. • 1968/1969 sustained conflict began (colloquially, ‘The Troubles’) which was to last for over three decades • Reasons for its protraction: – exogenous; – more common endogenous (McGarry and O’Leary 1995). Education in transitional contexts: North(ern/of) Ireland • Impact on a small population of just over 1.6 million people: – over 3700 people killed – 47,000 people injured in 16,200 bombing and 37,000 shooting incidents; – an estimated 7000 people (mostly Catholic) internally displaced (Consultative Group on the Past 2009); – over 2000 people interned without trial and over 40,000 people imprisoned due to conflict related convictions (McEvoy and Shirlow 2008). • Deepening community division and high levels of social disadvantage • Prolonged peace process • Belfast/‘Good Friday Agreement’ of 1998 Education in transitional contexts: North(ern/of) Ireland • Engagement with the processes of transitional justice – early release of prisoners, reform of policing and the criminal justice system, demilitarisation and the decommissioning of ‘paramilitary’ weapons, reintegration etc. • Victims • Truth recovery • Tension between justice and reconciliation Education in transitional contexts: North(ern/of) Ireland • Education system – Separate schools – Integrated schools – Shared Education • Curriculum – History education – Citizenship education Education in transitional contexts: history education • Support for teachers in promoting the critical enquiry needed to challenge entrenched views (Cole and Barsalou 2006). • Need for more nuanced history resources (Freedman et al. 2008), including ‘polyvocal histories’ (Paulson, 2006). • Should aim to present a more complex picture of the nature of conflict to challenge homogenised official historical narratives and partial unofficial histories (Emerson, 2012). Education in transitional contexts: citizenship education • Young people need to be provided with opportunities to engage critically not only with issues of identity, but also with the legacy of conflict and their own contribution as active citizens to the processes of transition. • This requires a shift from presenting conflict as a ‘contextual issue’ to overtly addressing conflict and promoting ‘critical respect’ for the principle that justice can be pursued without recourse to violence (Davies 2008). • Should aim to educate young people about the complex political processes involved in transition (Emerson, 2012). ‘Prison to Peace’: programme • Complexity of conflict • Intricacies of conflict transformation and transition • ‘Political generosity’ (Emerson, 2012) Education in transitional contexts: ‘political generosity’ • Capacity for ‘political generosity’ is the ability to legitimise the cultural and political identity of those with opposing views, primarily on the basis of their right to hold them. • Individuals having confidence in their own cultural and political identity and in their right to hold and express it (McEvoy (Emerson) et al 2006). • Both requires and engenders trust: – development of a ‘psychological repertoire that accepts, recognizes, respects, legitimizes, humanizes and personalizes the rival or discriminated group’. (Bar-Tal 2004, 263) – politically pragmatic in nature, focused on concrete issues related to conflict transformation (McEvoy (Emerson) et al, 2006; Emerson, 2012). ‘From Prison to Peace’: programme • Loyalist groups – Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) – Ulster Defence Association (UDA) • Republican groups – IRA (Provisional) – IRA (Official) – INLA Card Cluster: becoming involved ‘From Prison to Peace’: programme ‘From Prison to Peace’: programme Silent Conversation: the prison experience ‘From Prison to Peace’: programme ‘Prison to Peace’: programme • Complexity of conflict • Intricacies of conflict transformation and transition • ‘Political generosity’ (Emerson, 2012) ‘Prison to Peace’: evaluation • Cluster randomized controlled trial – Impact of programme – Outcomes related to knowledge, attitudes and behaviours – The trial involved 864 young people (with 497 young people matched across pre- and post- test) aged 14-17 years, from 14 post-primary school settings (7 intervention schools, 7 control schools). • Case studies – Process(es) of teaching controversial issues – Features of school ‘readiness’ • Stakeholder interviews – Role of curriculum in addressing conflict and its legacy – Relationship between statutory curriculum and nonstatutory initiatives • Young People’s Advisory Group Programme Outcomes OUTCOMES Knowledge 1. Increase in awareness of the complexity of conflict in Northern Ireland 2. Increased knowledge of the conflict, processes of transition and conflict transformation Attitudes 3. Reduction in sectarian prejudice (exploratory only) 4. Increase in respect for political diversity and, more specifically, acceptance that other political positions/opinions are legitimate Intended behaviours 5. Reduction in intention to use/support the use of violence to deal with divisions and conflict 6. Increase in intention to be politically engaged. Findings • Clear evidence of the positive effects of Prison to Peace on young peoples’ knowledge, attitudes and behaviours. • Specifically, the programme had the following statistically significant effects: – increased knowledge of the conflict, processes of transition and conflict transformation; – increased support for using non-violent means to deal with conflict; – reduction in sectarian prejudice; – increased likeliness of young people becoming politically engaged. (Effect sizes were sizeable, with effects ranging from .17-.42.) • Although the intervention schools reported higher scores (compared to the control schools) across measures of direct participation in politics and respect for political differences, the difference was not statistically significant Additional findings • increased awareness of the complexity of the conflict • increased optimism in relation to ‘permanent peace’; • increased trust in civic and political institutions; • no change in relation to the young people’s strength of cultural identity; • high levels of enjoyment of all aspects of the programme. In sum: • Foregrounding the nature of conflict and the processes of conflict transformation in the curriculum, through the narratives of those who were directly involved in conflict (arguably the most contentious ‘voices’), has a positive impact on young people. Findings – young people The young people enjoyed engaging with the narratives of the exprisoners, valuing these first-hand accounts which they saw as grounded in reality. They also appreciated learning about the impact of being involved in violence, in terms of imprisonment and the effect it had on families. ‘It brings sort of like, reality to it…because they’re (referring to ex-prisoners) telling us about it from their views.’ ’It makes you recognise about what actually happened and what happened to the families and stuff like that, the aftermath of it.’ Findings – young people Acknowledged the benefits it holds, for example: • the programme increased their knowledge and awareness of the reality and complexity of the conflict; • helped them make sense of their current socio-political context; • helped them see how society could ‘move forward’. ‘You can’t really move on unless you know about it [the ‘Troubles’]. Because if you’re just going into it like not knowing about it and just being like blind from it, then how do you expect to move on if you don’t know what happened and how to change it.’ ‘I think it’s [the programme] important because it gets rid of the prejudices we have against certain groups of people and the stories that we’ve heard from the Troubles, but with the Prison to Peace, that programme, you were able to see both sides of the story so you could see what actually happened’. Findings – young people Acknowledged the benefits it holds, for example: • the programme increased their knowledge and awareness of the reality and complexity of the conflict; • helped them make sense of their current socio-political context; • helped them see how society could ‘move forward’. ‘You can’t really move on unless you know about it [the ‘Troubles’]. Because if you’re just going into it like not knowing about it and just being like blind from it, then how do you expect to move on if you don’t know what happened and how to change it.’ ‘I think it’s [the programme] important because it gets rid of the prejudices we have against certain groups of people and the stories that we’ve heard from the Troubles, but with the Prison to Peace, that programme, you were able to see both sides of the story so you could see what actually happened’. Findings – teachers School leaders and teachers in the intervention schools recognized the educational benefits of engaging with ‘Prison to Peace’. They saw the programme as providing opportunities to: • challenge the myths associated with the conflict; • help young people make sense of their socio-political context; • assist young people in developing their own perspectives. However, it is important to note that the schools involved in this study were clearly ‘ready’ to engage with controversial and sensitive issues related to the conflict. Findings – parents The parents interviewed, though to a certain extent apprehensive initially about the programme, were supportive of their school engaging with the programme. ‘Well I, I signed [the permission form for her son to attend the panel]…I had no issue signing it because I have great faith that the school knows what it’s at and I thought ‘No, that’s fine’ even though part of me thought ‘Oh God’.’ In particular they: • recognized the value of their children learning about their socio-historical context from engaging with ex-prisoners; • welcomed the dialogue it created between them and their children about the ‘Troubles’ and the current nature of Northern Irish society. Findings – educational stakeholders Notwithstanding associated sensitivities, there were numerous benefits recognised by the educational stakeholders interviewed: • they believed it helped young people make sense of their present situation; • it also helped develop an awareness of the complexity of the Northern Ireland conflict; • they recognised the value of engaging with the perspectives of ex-prisoners as part of a broader engagement of a range of voices from the conflict. They suggested that there is a need for a co-ordinated approach to addressing the past in the curriculum to ensure that the range of educational initiatives dealing with related issues can work together to maximise impact. GROUP DISCUSSION Conclusion • While there are many ways in which the ‘Troubles’ could be addressed through the curriculum, ‘Prison to Peace’ provides young people with a unique perspective on conflict, its impact and on the processes of conflict transformation. • This research indicates that addressing issues of the conflict and its legacy helps young people understand the nature of their current societal context, make sense of division resulting from conflict and, arguably, as a consequence reduces sectarian prejudice. Conclusion • Curriculum programmes need to create space for ‘productive conflict’ in relation to the past and its legacy. • This requires nuanced resources which convey cognitively and emotionally engaging personal narratives to disrupt both homogenised official historical narratives and potentially biased unofficial histories generated at home and in communities. • The findings from this study provide an evidence base to suggest that through direct engagement with the narratives of those involved in conflict, young people can learn not only about but from the past, and thus develop the skills required to understand and negotiate the complex political contours of a society emerging from conflict. ‘History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived, however, if faced with courage, need not be lived again.’ Maya Angelou