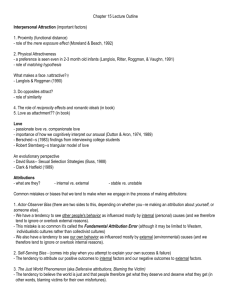

Attributions *Attribution- Personally constructed casual explanation

advertisement

Attributions *Attribution- Personally constructed casual explanation for a particular event, such as a failure. It is a cognitive factor affecting motivation to the extent to which learners make mental connections between the things they do and the things that happen to them. Examples: If you make an A on an exam You studied hard You’re smart You failed the exam You didn’t study enough You studied the wrong things The amount of time you spend studying for your upcoming exams will depend to some degree on how you’ve interpreted your earlier test grades. Learners form attributions for many events in their daily lives- not only about why they do well or poorly on tests and assignments but also about why they are popular or unpopular with peers, why they are skilled athletes or total klutzes, and so on. Their attributions vary in three primary ways: 1.) Locus: Internal vs. external Leaners sometimes attribute the causes of events to internal things-to factors within themselves. Thinking that a good grade is due to your own hard work and believing that a poor grade is due to your lack of ability are examples of internal attributions. At other times, leaners attribute events to external things- to factors outside themselves. Concluding that you won a spelling bee only because you were asked to spell easy words is an example of external attributions. 2.) Stability: Stable vs. unstable Sometimes learners believe that events are due to stable factors- to things that probably won’t change much in the near future. For example, if you believe that you do well in science because of your innate intelligence or that you have trouble making friends because you’re overweight, then you are attributing events to stable, relatively long-term causes. Unstable factors- things that can change from on time to the next, such as thinking you won a tennis game because of a lucky break. 3.) Controllability: Controllable vs. uncontrollable Controllable factors- things that they can influence and change such as, if you think that a classmate invites you to his party because you always smile and say nice things to him. Uncontrollable factors- things to which they have no influence over such as, if you think you were chosen for the school play because you look right for the part. Attributions are an excellent example of knowledge construction in action: Learners interpret new events in light of existing knowledge and beliefs about themselves and the world and then develop what seems to be a reasonable explanation of what has happened. Because attributions are self-constructed, they may or may not reflect the true state of affairs. ***How attributions influence affect, cognition, and behavior Attributions influence a number of factors that either directly or indirectly affect learners’ future performance. First, attributions influence learners’ emotional reactions to success and failure. Leaners feel proud about their successes and guilt and shame about their failures. Second, attributions have an impact on expectations for future success and failure. When learners attribute their successes and failures to stable factors-perhaps to innate ability or inability- they expect their future performance to be similar to their current performance. Third, attributions affect effort and persistence. Learners who believe their failures result from their own lack of effort are apt to try harder and persist in the face of difficulty. Finally, attributions influence learning strategies and classroom performance. Learners who expect to succeed in the classroom and believe that academic success is a result of their own doing are more likely to apply effective learning and self-regulation strategies, especially when they’re taught these strategies. Given all of these effects, it should not surprise you to learn that students with internal, controllable attributions for classroom success-rather than external ones they can’t control- are more likely to achieve at high levels and graduate from high school. ***Developmental trends in attributions Young children become increasingly able to distinguish among the various possible causes of their successes and failures: effort, ability, luck, task difficulty, and so on. Elementary school grades tend to attribute their success to hard work and are usually optimistic about their chances for future success as long as they try hard. Later many begin to attribute their success and failure to an inherited ability- for instance, intelligence-which they perceive to be fairly stable and beyond their control. Those with an incremental view believe that intelligence can and does improve with effort and practice. In contrast, those with an entity view believe that intelligence is a distinct ability that is built in and relatively permanent. Yet factors in learners’ current environment also play a role. ***Mastery orientation versus learned helplessness As children grow older, they gradually develop predictable patterns of attributions and expectations for their future performance. Over time, some learners develop an “I can do it” attitude known as a mastery orientation- a general sense of optimism that they can master new tasks and succeed in a variety of endeavors. Other learners, develop and “I can’t so it” attitude known as learned helplessness- a general sense of futility about their chances for future success. When working with students who have learned helplessness, be consistent and persistent in your efforts to help them succeed. In addition, students should know that they have a variety of resources- their teacher, their peers, self-instructional computer programs, volunteers tutors, and so on- to which they can turn to in times of difficulty. ***Teacher expectations and attributions Teachers typically draw conclusions about their students relatively early in the school year, forming opinions about each one’s strengths, weaknesses, and potential for academic success. Even the best teachers sometimes make errors in their judgments. Continually ask yourself whether you are giving inequitable treatment to students for whom you have low expectations. Also reflect on your beliefs about students’ intelligence: Are you taking an incremental view that gives you optimism about future progress? Teachers’ beliefs about the reasons for students’ performance often reveal themselves in the things they say to students. Success: “You did it! You’re so smart!” “Your hard work has really paid off!” Failure: “Maybe this just isn’t something you’re good at. Perhaps we should try a different activity.” “Why don’t you practice a little more and then try again?” All of these comments are intended to make a student feel good, but notice the different attributions they imply. ***How teacher expectations and attributions affect students’ achievement Teachers who hold high expectations for their students are more likely to give specific feedback about the strengths and weaknesses of students’ responses. When teachers repeatedly give students low ability messages, students begin to see themselves as their teachers do and to behave accordingly. In such cases, teachers’ expectations and attributions may lead to a self- fulfilling prophecy: What teachers expect students to achieve becomes what students actually do achieve. Be especially careful not to form unwarranted expectations for students at transition points in their academic careers. As teachers, we are most likely to motivate students to achieve at high levels when we have optimistic expectations for their performance and when we attribute their successes and failures to things over which either they or we have control. By teaching effective strategies, not only do we promote students’ academic success, but we also promote their beliefs that they can control their success. ***Forming Productive Expectations and Attributions for Student Performance Remember that teachers can definitely make a difference. Look for strengths in every student. Consider multiple possible explanations for students’ low achievement and classroom misbehavior. Communicate optimism about what students can accomplish. Objectively assess students’ progress, and be open to evidence that contradicts your initial assessments of students’ abilities. Attribute students’ successes to a combination of high ability and controllable factors such as effort and learning strategies. Attribute students’ successes to effort only when they have actually exerted considerable effort. Attribute students’ failures to factors that are controllable and easily remedied. When students fail despite making obvious effort, attribute their failures to a lack of effective strategies and help them acquire such strategies. Attributions Matching Game Self-fulfilling prophecy Personally constructed casual explanation for a particular event, such as a success or failure. Incremental view of intelligence General, fairly pervasive belief that one is capable of accomplishing challenging tasks. Attribution General, fairly pervasive belief that one is incapable of accomplishing tasks and has little or no control of the environment. Entity view of intelligence Situations in which expectations for an outcome either directly or indirectly lead to the expected result. Learned helplessness Belief that intelligence is a distinct ability that is relatively permanent and unchangeable. Mastery orientation Belief that intelligence can improve with effort and practice.