Chapter 31: Fallacies of Weak Induction

advertisement

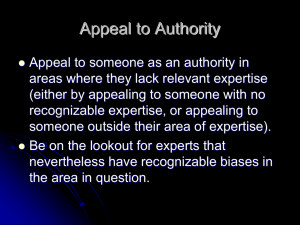

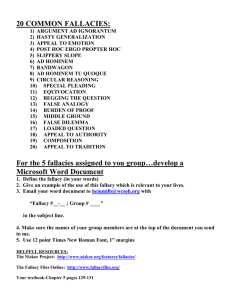

Chapter 31: Fallacies of Weak Induction Appeal to Authority (pp. 359-360) • The fallacy of appeal to authority occurs when someone is taken to be an authority on a particular topic when he or she is not. As we acknowledged in Chapter 11, there are criteria for evaluating a person’s testimony. • A. Questions of background regarding the area – If a person is testifying outside of his or her area of expertise, there are grounds for claiming an illegitimate appeal to authority. Appeal to Authority (pp. 359-360) – If an actor or sports personality claims that a certain brand of pain reliever is particularly effective, you have little reason to believe the claim: pain relief is outside the area of expertise of an actor or sports personality. – Commercial endorsements by famous personalities always involve a potential conflict of interest. • A person has a conflict of interest if he or she appears to have mixed motives in making a claim. • When a person famous for his or her sports prowess, acting prowess, etc. appears in a commercial for cereal, or cars, or hardware, or anything else that is outside his or her clear area of expertise, there is a conflict of interest: you don’t know whether the testimony rests upon their sincere beliefs or the money they’re paid to be in the commercial. The question arises even if you have a person known for his or her prowess in sports who is advertising sporting goods. Appeal to Ignorance (p. 361) • The general form of this argument is “There is not evidence that x, so not x,” or “There is no evidence that not x, so x.” • A. Fallacious cases – Fallacious cases arise when the evidence on both sides of a question is open: • “There is no evidence that extraterrestrial creatures do no live on earth, so they do.” – You have to be careful, since there are cases in which the lack of positive evidence is good negative evidence. If there is no reason to believe that your roommate smokes, there is good reason to believe that your roommate does not smoke, for example. Appeal to Ignorance (p. 361) • B. Ties to testimonial evidence – If an authority in a field, or all authorities in a field, contend that there is no reason to believe some statement p, you have good reason to believe that not p. The fact that virtually all scientists agreed that Fleishmann and Pons did not produce cold fusion in 1989 is good reason to believe that they did not. Hasty Generalization (pp. 361-362) • A hasty generalization is a generalization drawn from either too few cases, or atypical cases, or both. – “My Pontiac is unreliable. So, all Pontiacs are unreliable.” – This is drawn from one case. It is also a problematic case: My Pontiac is nearly a decade old, and it is one of the less expensive models. False Cause (pp. 362-365) • The fallacy of false cause occurs when a false causal claim is taken as a premise. • Most superstitious beliefs commit this fallacy. • A. Taking something to be a cause when it is not (non causa pro causa) – I carry a rabbit’s foot. That’s why I’ve been blessed with good fortune. – There is no causal connection between carrying a rabbit’s foot and good fortune. If you have any doubts, just ask the rabbit. False Cause (pp. 362-365) • B. One event occurred before another, so it was the cause (post hoc ergo propter hoc) – I walked under a ladder on the way to work. The whole day was terrible. It’s all because I walked under a ladder. • The walking under a ladder occurred before the terrible, awful, horrid day, but given that alone, there is no reason to believe there was any connection. • Of course, if someone dropped paint on you when you walked under the ladder, there could be a causal connection between the first action and the resulting day, but walking under the ladder was not itself the cause of the state of the day. Slippery Slope (Wedge) (pp. 365-366) • There is a chain of causes, and at least one causal claim is false. • Typically, in a slippery slope argument things begin bad and grow progressively worse. • A. Causal chains – In its fallacious form, there is a hypothetical syllogism with a false premise. – “If you smoke cigarettes, you’ll try marijuana. If you try marijuana, you’ll try heroin. If you try heroin, you’ll become addicted to cocaine. So, you don’t want to smoke cigarettes.” – Some people who smoke cigarettes try marijuana, but they do not all do so. The argument is fallacious. Slippery Slope (Wedge) (pp. 365-366) • B. Nonfallacious slippery slopes – There are causal chains. Sometimes things begin bad and grow progressively worse. So, you need to check to see whether all the premises of the relevant hypothetical syllogism are true. Weak Analogy (pp. 366-367) • You commit the fallacy of weak analogy if (see the criteria in Chapter 25): – There are claims of similarities where the similarities are lacking. – There are significant disanalogies. • “Critical thinking tests are like mathematics tests insofar as they are both written on paper. Calculators are helpful when taking mathematics tests. So calculators are helpful when taking critical thinking tests.” • There are significant disanalogies between mathematics tests and critical thinking tests, but if you think a calculator will help, you’re welcome to use one!